19 Cancer in pregnancy

Cancer during pregnancy poses a very challenging situation. Cancer complicates 0.02–0.1% of pregnancies. The oncologist faces the difficult situation of optimizing the care of the mother without causing harm to the foetus. The common tumours diagnosed during pregnancy are malignant melanoma, breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Diagnostic work-up

All patients require a complete physical examination. Although histological diagnosis with fine needle aspiration cytology and core biopsies are safe, general anaesthesia during the first trimester carries a 1–2% risk of spontaneous abortion. Endoscopic biopsies as well as lumbar puncture and bone marrow examinations are safe. Radiological investigations should be restricted to minimize the foetal exposure to ionizing radiation. A foetal exposure dose of 1 mGy is considered safe. Box 19.1 shows various imaging procedures and uterine/foetal exposure dose. A dose of less than 100 mGy (10 cGy) is associated with less than 1% risk of foetal malformation and carcinogenesis and hence, in the event of inadvertent exposure of pregnant women to radiation, termination of pregnancy is not recommended if the foetal dose does not exceed this limit.

Box 19.1

Uterine/foetal radiation dose during various radiological investigations

| Investigation | Uterine/foetal dose |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray | 0.000005 Gy |

| Abdominal X-ray | 0.022 Gy |

| Mammogram | 0.04 Gy |

| Chest CT scan | 0.002 Gy |

| Abdominal CT scan | 0.02 Gy |

| Pelvic CT | 0.07 Gy |

| Barium enema | 0.036 Gy |

| IVU | 0.045 Gy |

| Bone scan | 0.018–0.045 Gy |

1 Gy = 100 cGy = 1000 mGy

Surgery

Surgery can be performed without major risk to the patient during the first two trimesters, but with a 1–2% risk of foetal loss, small risk of low birth weight (RR 1.5–2.0) and premature delivery. Foetal harm during surgery is due to various factors including placental transfer of drugs, intraoperative complications such as hypoxia, hypotension, and long-term supine positioning of mother during surgery causing placental underperfusion.

Radiotherapy

The developing embryo or foetus is extremely sensitive to ionizing radiation, which can cause foetal loss, malformations, growth retardation and defects in intelligence. Radiotherapy is therefore contraindicated for abdominal and pelvic malignancies during pregnancy. Several studies support the use of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer, breast cancer and brain tumours. Radical radiotherapy to the head and neck and brain can be achieved with a foetal dose of less than 100 mGy (Box 19.2). During radiotherapy to the breast and chest wall, the dose to the foetus increases with gestational age. The foetal dose depends on the radiation field, dose, the distance between the edge of radiation field and foetus, and the machine and its shielding measures.

Box 19.2

Foetal radiation dose during radiotherapy

| Radiotherapy | Foetal dose |

|---|---|

| Cervical cancer | 45–50 Gy |

| Mantle field | 0.014–0.13 Gy |

| Breast cancer | 0.14–0.18 Gy |

| Brain tumour and head and neck cancer | 0.0015–0.08 Gy |

Systemic treatment

Alkylators and anti-metabolites are the most teratogenic and have high abortive potential. Vinca alkaloids, anthracyclines, 5-fluorouracil, cytarabine, taxanes and platinums appear to be relatively safe.

Management of specific cancers

Breast cancer

Breast cancer in pregnancy can occur at any time during pregnancy and within 12 months postpartum. The median age at diagnosis is 33 years and the commonest presentation is a painless palpable lump (80–95%). Presentation is similar to non-pregnant breast cancer. Diagnosis may be delayed accounting for a 2.5-fold increased risk of advanced cancers (40%) at presentation. Diagnosis is by mammogram, ultrasonography and non-enhanced MRI. Cytology may be difficult to interpret due to pregnancy associated changes and hence needle biopsy or open biopsy is diagnostic. The most common histological type is invasive ductal carcinoma (80–90%) followed by lobular carcinoma. The majority of tumours are high grade with axillary involvement (60–90%). Hormone receptors are negative in 40–70% and HER2 positive in 28–58%.

Most series suggest that pregnancy does not affect the natural course of illness or prognosis.

Melanoma

Common presenting symptoms are change in size and colour and bleeding or ulceration of pre-existing melanotic lesion as with melanomas diagnosed outside pregnancy (p. 234). Patients can present with lymphadenopathy and features of metastatic disease. Evaluation includes full clinical examination and skin examination followed by excisional biopsy, in limited disease. The commonest type is superficial spreading (74%) followed by nodular melanoma (16%). In the absence of clinical features of metastases, chest X-ray and USS abdomen are sufficient for staging.

The surgical excision margin is based on thickness of primary (p. 234). Treatment of metastatic melanoma is essentially palliative. Pregnancy termination should be discussed with the patient. Chemotherapy using dacarbazine or cisplatin can be given after the first trimester if the patient decides to continue with the pregnancy.

Lymphomas

The most common type of HD is nodular sclerosis and 90% of pregnancy associated NHL are high grade.

When the diagnosis is made in the first trimester, termination of pregnancy is considered particularly in those with B-symptoms, bulky stage I–II, stage III–IV and high-grade lymphoma. If the patient refuses termination, single agent vinblastine may be given until the second trimester. The preferred regime for HD is ABVD and for NHL is CHOP (p. 298). Treatment may be delayed until delivery in low volume low-grade NHL. If treatment is needed for low-grade NHL, single agent chemotherapy or limited field radiotherapy is used.

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is diagnosed rarely in pregnancy with 35% adenocarcinoma, 30% borderline ovarian tumour and 35% germ-cell/sex cord stromal tumour (most common dysgerminoma). Most of the borderline and germ cell tumours are diagnosed at an early stage.

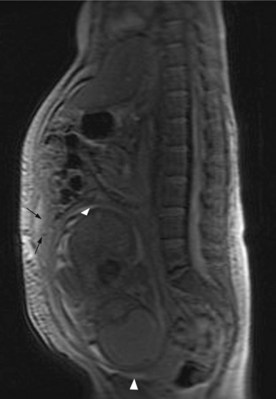

Staging includes chest X-ray, abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and MRI if indicated (Figure 19.1). CA-125, beta-hCG and AFP are raised in pregnancy.

Laparotomy or laparoscopy is indicated when there is suspicion of an ovarian lesion (persistent solid or complex mass lesion of >6 cm with associated ascites). Surgical principles follow that of ovarian cancer in non-pregnant women (p. 197). Maximum feasible cytoreduction is attempted and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy after week 7 is feasible as the hormonal function will be taken up by placenta. Other option is neoadjuvant chemotherapy depending on the stage of gestation. In high-grade bulky tumours hysterectomy is also advisable. Chemotherapy may be administered after the first trimester.

Psychosocial support

A diagnosis of cancer during pregnancy is an extremely distressing situation for the patient and family, as they may have to decide about future plans which may not include both of them. This necessitates provision of adequate psychosocial support for both the parents (and probably grandparents!). Needless to say that there will be anxiety about the baby, though evidence shows little harm to date (but is minimal). The risks of a genetically associated cancer in the child should be evaluated by clinical genetics criteria (p. 45) but are not affected by being diagnosed in pregnancy.

Azim HAJr, Peccatori FA, Pavlidis N. Treatment of the pregnant mother with cancer: a systematic review on the use of cytotoxic, endocrine, targeted agents and immunotherapy during pregnancy. Part I: Solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:101-109.

Azim HAJr, Pavlidis N, Peccatori FA. Treatment of the pregnant mother with cancer: a systematic review on the use of cytotoxic, endocrine, targeted agents and immunotherapy during pregnancy. Part II: Hematological tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:110-121.

Kal HB, Struikmans H. Radiotherapy during pregnancy: fact and fiction. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:328-333.

Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Cancer and pregnancy: poena magna, not anymore. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:126-140.