5 Cancer genetics

Introduction

The last two decades have seen rapid expansion in our understanding of the genetic origins of cancers. Between 5–10% of cancers are due to inheritance of alterations in genes that confer a high life-time risk of certain malignancies, such as breast, colorectal cancer (see Table 5.1), and very rare tumours.

Table 5.1 The risk of common cancers associated with inherited cancer syndromes

| Tumour site | Genes associated with relative risk of >5.0 | Cancer syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | BRCA1/2 | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome |

| TP53 | Li–Fraumeni syndrome | |

| PTEN | Cowden syndrome | |

| CDH1 | Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome | |

| STK11 | Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | |

| Colorectal | APC | Familial adenomatous polyposis |

| MUTYH | ||

| MLH1 | Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer) | |

| MSH2 | ||

| MSH6 | ||

| PMS2 | ||

| Pancreatic | BRCA2 | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome |

| BRCA1 | ||

| MSH2 | Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer) | |

| MLH1 | ||

| STK11 | Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | |

| TP53 | Li–Fraumeni syndrome | |

| PRSS1 | Hereditary pancreatitis | |

| SPINK1 | Familial atypical mole malignant melanoma syndrome (FAMMM) | |

| CDKN2A | ||

| Prostate | BRCA2 | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome |

| Endometrial | MLH1 | Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer |

| MSH2 | ||

| MSH6 | ||

| PMS2 | ||

| Ovarian | BRCA1/2 | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome |

| MLH1 | Lynch syndrome | |

| MSH2 |

Mechanisms of inherited cancer

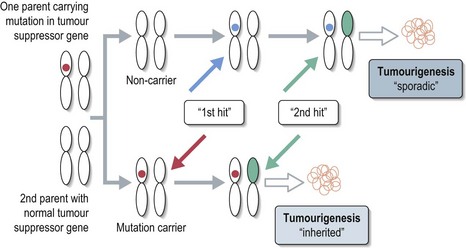

Tumorigenesis involves contributions from two classes of genes. Oncogenes control cell growth and proliferation under normal circumstances, but once inappropriately activated or overexpressed can promote rapid clonal expansion. Tumour suppressor genes normally inhibit abnormal cell proliferation; reduced expression of these genes can result in uncontrolled cell division. Almost all hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes are due to the inheritance of a germline mutation in a tumour suppressor gene. The inherited mutation inactivates one copy of the gene and the subsequent development of a mutation in the remaining ‘normal’ copy of the gene results in failure of a cell to produce the tumour suppressor protein (Knudson ‘two-hit’ hypothesis – see Figure 5.1).

Diagnosis

Analysis of DNA for mutations in known cancer predisposition genes is performed in a limited number of specialist molecular genetics laboratories using DNA derived from a peripheral blood sample. The gold standard is direct sequencing of the whole gene but this is generally not commercially viable for very large genes such as BRCA1/2. Screening for pathogenic mutations is therefore often limited to analysis of coding regions only, or regions of the genes which carry the greatest density of reported mutations. Additional tests are required to detect gene deletions. A full screen for unknown mutations will take several weeks to process. ‘Predictive testing’, in which genetic testing is directed at establishing whether or not an individual has a specific mutation carried by another family member, is faster.

Genetic counselling

It is essential that any individual considering undergoing genetic screening for an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome receives expert counselling prior to testing and on receiving their result. Patients must be advised that failure to detect a mutation does not always mean that no mutation is present and that further results may become available in the future when genetic testing may become more sophisticated. The roles of genetic counselling are summarized in Box 5.1.

Box 5.1

The roles of the genetic counsellor

The remainder of this chapter will look in more detail at inherited breast and colorectal cancer, and the most common cancer predisposition syndromes.

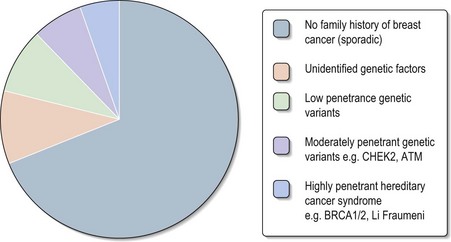

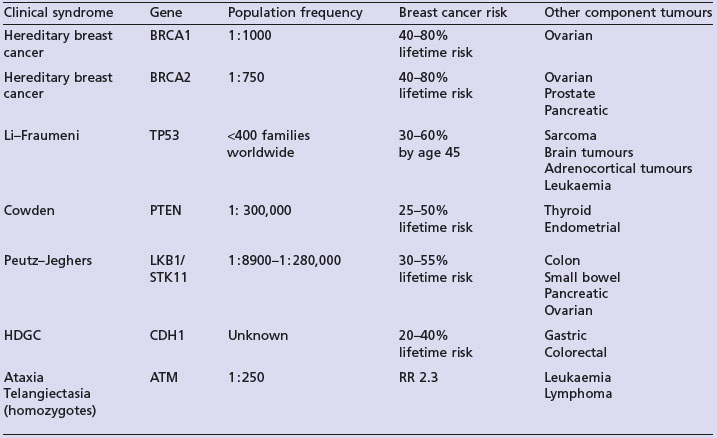

Inherited breast cancer

Studies indicate that 20–30% of breast cancer patients report a positive family history of this condition (Box 5.2). Approximately 5% of all breast cancer cases are thought to be due to highly penetrant autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndromes (Figure 5.2). The two most frequent highly penetrant breast cancer susceptibility genes are BRCA1 and BRCA2 where in some families lifetime penetrance for breast cancer can reach 80% but penetrance is clearly modified by other genetic and environmental factors. Much rarer syndromes including Li–Fraumeni, Cowden, Peutz–Jeghers and hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) syndromes can be recognized either by other clinical manifestations or by the pattern of cancers in the family (Table 5.2). Lifetime breast cancer risk for carriers of these mutations is in the order of 20–100%. It is likely that most familial clusters of breast cancer are the consequence of multiple low penetrance cancer susceptibility genes acting in conjunction with environmental factors. Within the last few years a number of large case-control studies have identified variants in DNA repair genes (e.g. CHEK2, ATM, BRIP1 and PALB2), which double the risk of breast cancer. The population prevalence of these variants seems to be in the order of 1–5%.

Box 5.2

Women at increased risk of breast cancer

Women are generally considered to be at increased risk of breast cancer if they have:

Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome

Genetics and pathology

BRCA1 and BRCA2 act as classical tumour suppressor genes; inheritance of mutations occurs in an autosomal dominant fashion and loss of the unmutated allele is found in tumour specimens. The precise functions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene products remain unclear but evidence indicates that these proteins are involved in DNA repair and transcription regulation, with additional roles in cell cycle checkpoint control and cytokinesis. Sporadic breast cancers do not contain BRCA1 mutations and very rarely demonstrate BRCA2.

Diagnosis

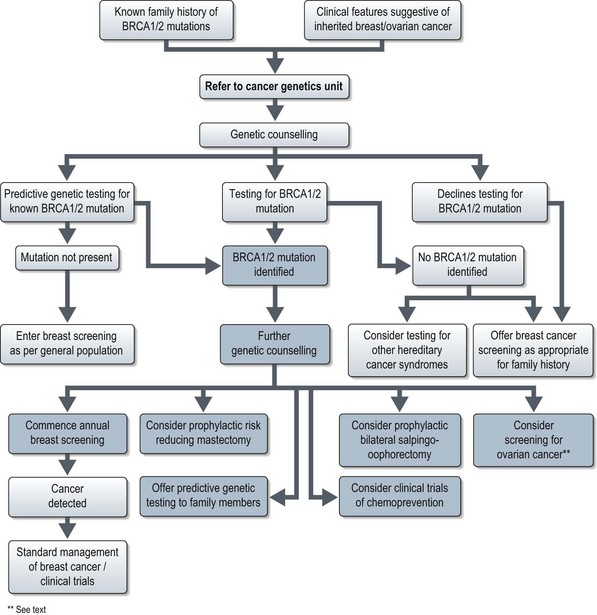

A number of scoring systems exist to estimate the likelihood of a family carrying BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, e.g. the Gail model. Most cancer genetic units recommend screening for BRCA 1/2 mutations if the chance of carrying a mutation is estimated at more than 20%. Oncologists should consider the possibility of an underlying BRCA1/2 mutation in breast cancer patients with the clinical features listed in Box 5.3.

Secondary prevention

Regular breast screening by mammography, together with clinical breast examinations, has been recommended for all patients with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations for some years. The 2006 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the management of familial breast cancer include a recommendation for annual MRI surveillance of all BRCA1/2 mutation carriers aged 30–49 as this method of screening has proved more sensitive then mammography. Screening for ovarian cancer remains under investigation.

Treatment of BRCA associated breast cancer

The management of potential BRCA1/2 mutation carriers is summarised in Figure 5.3 and discussed in Chapter 10 on breast cancer.

Inherited colorectal cancer

Approximately 5% of cases of colorectal cancer are due to an underlying hereditary cancer syndrome, with an increased representation amongst young colorectal cancer patients. Any features listed in Box 5.4 should raise the suspicion of a familial colorectal cancer syndrome.

Box 5.4

Clinical features suggesting underlying inherited predisposition to colorectal cancer*

Most familial cases are due to either hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch syndrome, which accounts for an estimated 2–3% of all colorectal cancers or familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), which accounts for less than 1% of all colorectal cancers. The key features of these two syndromes are summarized in Table 5.4.

| Clinical syndrome | Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) | Lynch syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 1 in 8000 | 1 in 1700 |

| Clinical features | Extensive gastrointestinal adenomatous polyps from young age with extremely high rate of malignant transformation. | High risk of early onset colon cancer associated with elevated risk of distinct spectrum of extra-colonic tumours. |

| Risk of colon cancer |

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Clinical features

FAP is characterized by the development of hundreds of colonic adenomatous polyps by the age of 20, with a risk of malignant transformation of almost 100%. The average age of diagnosis of colon cancer is 39 years. Patients are also at increased risk of other tumours listed in Table 5.4.

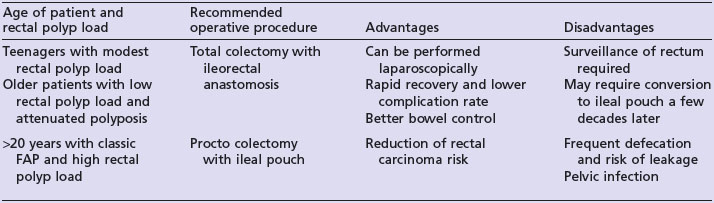

Primary prevention

Carriers of APC mutations should undergo surveillance colonoscopy annually from the age of 10 to 15 years. Prophylactic colectomy by the age of 20 years is recommended for those found to have multiple adenomas on surveillance. The type of operation performed is dependent on the polyp load within the rectum and the age of the patient (see Table 5.5). The cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent sulindac may both reduce duodenal adenoma formation but severe duodenal polyposis will require a Whipple’s resection.

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

Diagnosis

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines currently state that a clinical diagnosis of HNPCC requires the following minimum criteria, based on the Amsterdam II criteria (Box 5.5).

Box 5.5

Criteria for clinical diagnosis of HNPCC

At least three relatives must have a tumour associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (see Table 5.4) + all of the following criteria should be present:

Li–Fraumeni syndrome

First described in 1969, classic Li–Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), is a rare cancer susceptibility syndrome characterized by an autosomal dominant pattern of diverse neoplasms in children and young adults with a predominance of soft tissue sarcomas, osteosarcoma, and breast cancer and an excess of brain tumours, leukaemia, and adrenocortical carcinomas (see Box 5.6 for definition of classic LFS). Many additional tumours have also been reported in LFS families (see Table 5.6).

Box 5.6

Clinical features of classic LFS

Definition of classic LFS according to Chompret criteria

Table 5.6 Component tumours of classic Li–Fraumeni syndrome and other tumours associated with LFS

| Classic Li–Fraumeni component tumours | Other tumours associated with LFS |

|---|---|

Cowden syndrome

A clinical diagnosis of Cowden syndrome is currently made according to the International Cowden Consortium operational criteria (see Table 5.7).

Table 5.7 Criteria for clinical diagnosis of Cowden syndrome

| Pathognomonic criteria | Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|---|

Genetics

In 80% of Cowden syndrome families, the underlying mutation is in the PTEN (protein tyrosine phosphatase with homology to tensin) gene, located on chromosome 10. PTEN encodes a phosphatase which mediates cell growth, proliferation, cell cycle arrest and/ or apoptosis, hence acting as a tumour suppressor.

Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome

Clinical management

Screening for VHL tumours should be as set out in Table 5.8. Pre-natal and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis is now available for VHL when a mutation has been identified in a family.

Table 5.8 Onset of clinical features of VHL and recommended surveillance

| Age (years) | Clinical feature | Surveillance |

|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | Retinal angiomas | Retinal screening (from age 5) |

| 11–20 |

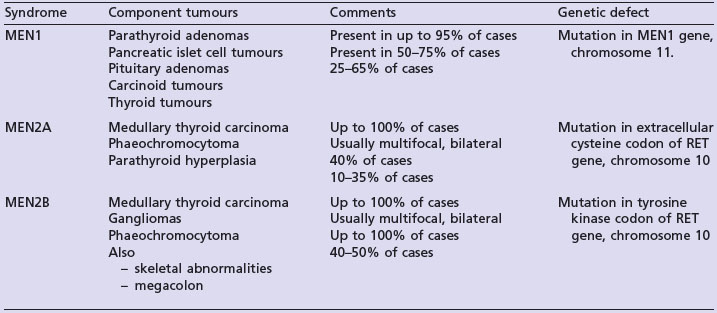

Multiple neuroendocrine neoplasia syndromes

The multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes are autosomal dominant disorders characterized by the development of multiple benign and malignant tumours of endocrine glands. The key clinical features of MEN1, MEN2A and MEN2B are summarized in Table 5.9.

Eng C. Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up: revised diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 2000;37:828-830.

Callender GG, Rich TA, Perrier ND. Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:863-895.

Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Eng J Med. 2008;359:2143-2153.

Garber JE, Offit K. Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:276-292.

Gonzalez KD, Noltner KA, Buzin CH, Gu D, Wen-Fong CY, et al. Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol.. 2009;27:1250-1256.

Guillem JG, Wood WC, Moley JF, Berchuck A, Karlan BY, et al. ASCO/SSO review of current role of risk-reducing surgery in common hereditary cancer syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4642-4660.

Kim WY, Kaelin WG. Role of VHL gene mutation in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4991-5004.

NCCN NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Colorectal cancer screening www.nccn.org

NCCN NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian www.nccn.org

NICE NICE clinical guideline 41: Familial breast cancer (issue date October 2006) www.nice.org