Ovarian Cancer (Epithelial)

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

Ultrasound Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Figures

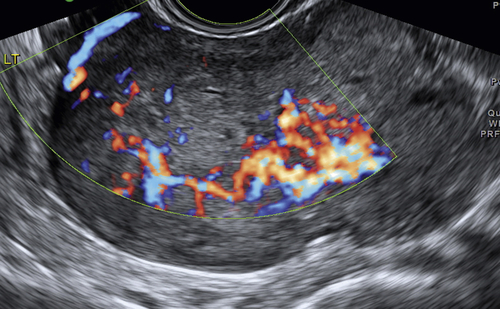

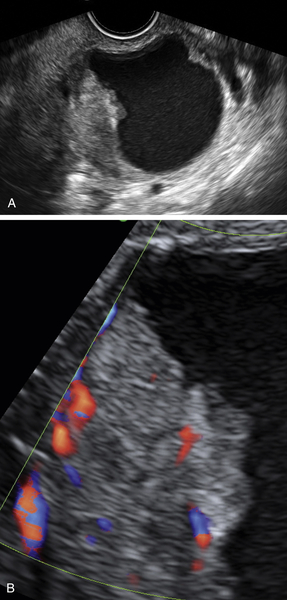

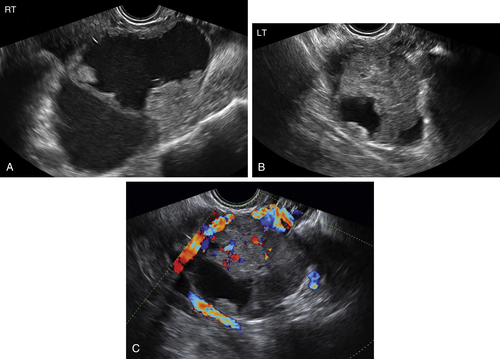

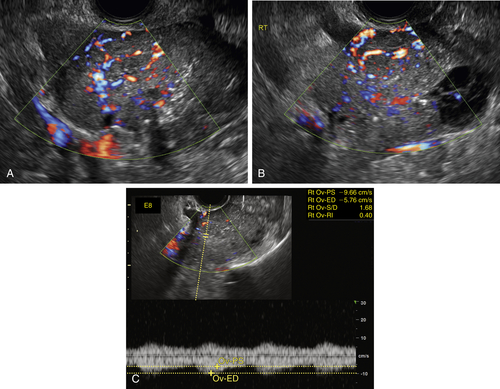

Figure O2-2 A to C, Ovarian cancer. Nine-centimeter ovarian cancer showing small cystic areas within a largely solid mass with extensive vascularity. C shows the low resistive index of 0.4 using spectral Doppler. This abundant diastolic flow is frequently seen in malignant tumors; however, the mere presence of disorganized blood vessels in the center of the mass is the most important Doppler finding.

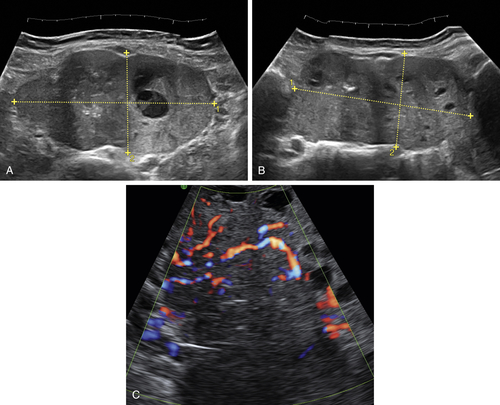

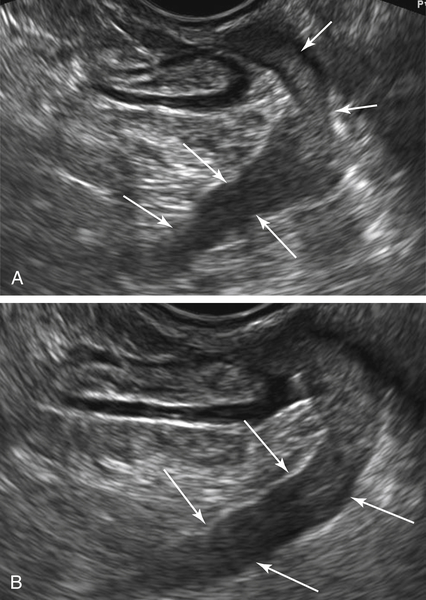

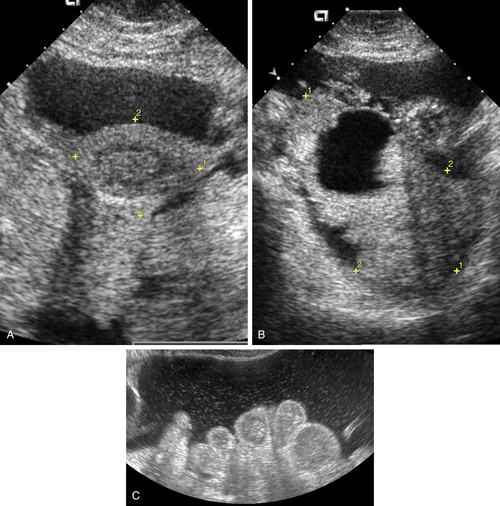

Figure O2-3 Advanced ovarian cancer. A shows a large amount of ascites anterior to the uterus (calipers) on a transverse view of the pelvis. B shows the large complex irregular mass (calipers), which was the ovarian tumor. Note the surrounding ascites. C shows the extensive ascites surrounding bowel loops, higher up in the abdomen.

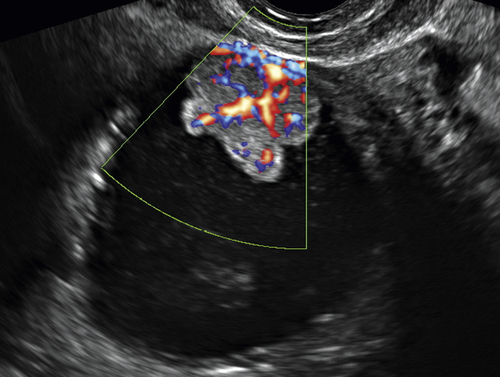

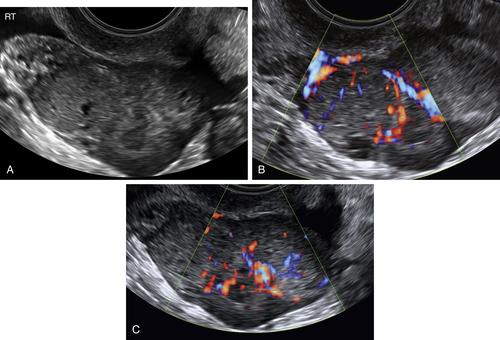

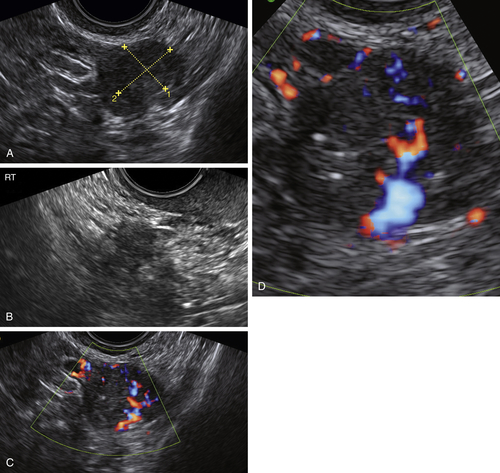

Figure O2-9 Stage 1 ovarian cancer in a 73-year-old patient. A shows an enlarged left ovary with a subtle 1.5-cm solid mass (calipers). B shows the normal (small) right ovary for comparison. C and D show the abundant blood flow to the small tumor. Typically it is difficult to demonstrate blood vessels within a normal postmenopausal ovary, making the flow pattern in the left ovary abnormal.

Videos

Suggested Reading

Alcázar J.L., Rodriguez D. Three-dimensional power Doppler vascular sonographic sampling for predicting ovarian cancer in cystic-solid and solid vascularized masses. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:275–281.

Ameye L., Valentin L., Testa A.C., Van Holsbeke C., Domali E., Van Huffel S., Vergote I., Bourne T., Timmerman D. A scoring system to differentiate malignant from benign masses in specific ultrasound-based subgroups of adnexal tumors. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:92–101.

Campbell S. Ovarian cancer: role of ultrasound in preoperative diagnosis and population screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:245–254.

Kaijser J., Bourne T., Valentin L., Sayasneh A., Van Holsbeke C., Vergote I., Testa A.C., Franchi D., Van Calster B., Timmerman D. Improving strategies for diagnosing ovarian cancer: a summary of the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:9–20.

Sharma A., Apostolidou S., Burnell M., Campbell S., Habib M., Gentry-Maharaj A., Amso N., Seif M.W., Fletcher G., Singh N., Benjamin E., Brunell C., Turner G., Rangar R., Godfrey K., Oram D., Herod J., Williamson K., Jenkins H., Mould T., Woolas R., Murdoch J., Dobbs S., Leeson S., Cruickshank D., Fourkala E.O., Ryan A., Parmar M., Jacobs I., Menon U. Risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women with ultrasound-detected ovarian masses: a prospective cohort study within the UK collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UKCTOCS). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:338–344.

Timmerman D., Ameye L., Fischerova D., Epstein E., Melis G.B., Guerriero S., Van Holsbeke C., Savelli L., Fruscio R., Lissoni A.A., Testa A.C., Veldman J., Vergote I., Van Huffel S., Bourne T., Valentin L. Simple ultrasound rules to distinguish between benign and malignant adnexal masses before surgery: prospective validation by IOTA group. BMJ. 2010;341:c6839.

Timmerman D., Valentin L., Bourne T.H., Collins W.P., Verrelst H., Vergote I. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: a consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:500–505.

Vang R., Shih E.M., Kurman R.J. Fallopian tube precursors of ovarian low- and high-grade serous neoplasms. Histopathology. 2013;62:44–58.