Cancer and its consequences

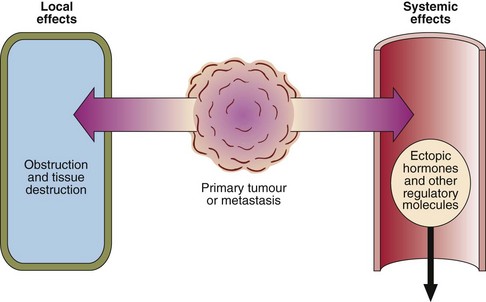

In Western societies one death in five is caused by cancer. The effects of tumour growth may be local or systemic (Fig 69.1), e.g. obstruction of blood vessels, lymphatics or ducts, damage to nerves, effusions, bleeding, infection, necrosis of surrounding tissue and eventual death of the patient. The cancer cells may secrete toxins locally or into the general circulation. Both endocrine and non-endocrine tumours may secrete hormones or other regulatory molecules.

A tumour marker is any substance that can be related to the presence or progress of a tumour (see pp. 140–141).

Local effects of tumours

Renal failure may occur in patients with malignancy for the following reasons:

Cancer cachexia

Impaired digestion and absorption.

Impaired digestion and absorption.

Competition between the host and tumour for nutrients. The growing tumour has a high metabolic rate and may deprive the body of nutrients, especially if it is large. One consequence of this is a fall in the plasma cholesterol level in cancer patients.

Competition between the host and tumour for nutrients. The growing tumour has a high metabolic rate and may deprive the body of nutrients, especially if it is large. One consequence of this is a fall in the plasma cholesterol level in cancer patients.

Increased energy requirement of the cancer patient. The host reaction to the tumour is similar to the metabolic response to injury, with increased metabolic rate and altered tissue metabolism.

Increased energy requirement of the cancer patient. The host reaction to the tumour is similar to the metabolic response to injury, with increased metabolic rate and altered tissue metabolism.

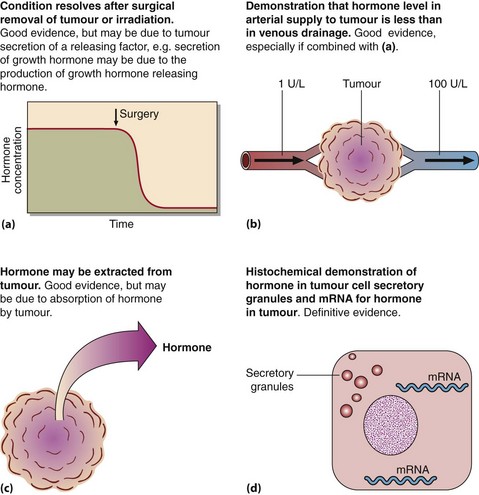

Ectopic hormones

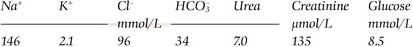

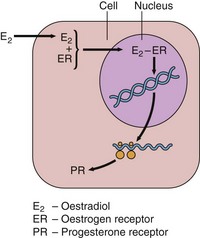

It is a characteristic feature of some cancers that they secrete hormones, even though the tumour has not arisen from an endocrine organ. Referred to as ectopic hormone production, hormone secretion by tumours has frequently been invoked but rarely proven (Fig 69.2). Small cell carcinomas are the most aggressive of the lung cancers and are the most likely to be associated with ectopic hormone production. Ectopic ACTH secretion causing Cushing’s syndrome is the most common. However, the classic clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome are not usually apparent in the rapidly progressing ectopic ACTH disorder. Biochemical features include hypokalaemia and metabolic alkalosis and these may be the sole indicators of the problem.