CANCER

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

It is estimated that up to 80% of patients with cancer seek complementary and alternative therapies, almost entirely as adjunctive treatment. A study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology reported that 88% of 102 people with cancer who were enrolled in phase I clinical trials (research studies in people) at the Mayo Comprehensive Cancer Center had used at least one CAM therapy.1 Of those, 93% had used supplements (such as vitamins or minerals), 53% had used non-supplement forms of CAM (such as prayer/spiritual practices or chiropractic care), and almost 47% had used both.

CANCER AND THE ESSENCE MODEL

Although it has just been said that cancer is different from other diseases, the ESSENCE principles of cancer prevention and management2 (see Chapter 6 from General Practice: The Integrative Approach by Kerryn Phelps and Craig Hassed, ISBN 9780729538046) are very similar whatever the cancer type. The important thing is to understand the principles, which are largely the same whatever the cancer, and not get concerned because there might be less information on one particular type of cancer. Although most research data is drawn from the more common cancers, the same rules apply for others.

PATIENT EDUCATION

In the most general sense, cancer is a disease in which a cell changes in such a way that it:

Staging

Cancers can be largely divided into two groups: solid and blood-borne malignancies.

Cancers are generally staged according to their level of spread and how aggressive or mutated they are. The TNM system is one of the most commonly used staging systems.3 This system has been accepted by the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Most medical facilities use the TNM system as their main method of cancer reporting.

The TNM system is based on the extent of the tumour (T), the extent of spread to the lymph nodes (N) and the presence of metastasis (M). A number is added to each letter to indicate the size or extent of the tumour and the extent of spread (Box 24.1).

BOX 24.1 TNM staging system

Source: National Cancer Institute 20043

| Primary tumour (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumour cannot be evaluated |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (early cancer that has not spread to neighbouring tissue) |

| T1, T2, T3, T4 | Size and/or extent of the primary tumour |

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated |

| N0 | No regional lymph node involvement (no cancer found in the lymph nodes) |

| N1, N2, N3 | Involvement of regional lymph nodes (number and/or extent of spread) |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be evaluated |

| M0 | No distant metastasis (cancer has not spread to other parts of the body) |

| M1 | Distant metastasis (cancer has spread to distant parts of the body) |

Hence, it is not just the primary prevention of cancer through healthy lifestyle that is important, but also secondary prevention through early detection and screening. There are many forms of screening for particular cancers, such as breast self-examination and mammography for breast cancer, faecal occult blood or colonoscopy for bowel cancer, digital rectal examination and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer and chest X-ray for lung cancer. Cancers picked up on routine screening are more likely to be in an earlier stage of growth and of a lower level of malignancy than cancers detected because they have produced symptoms.

Treatment

This having been said, if a patient feels obstructed, undermined or disempowered in their cancer management, if they are told there is nothing they can do for themselves, if they are told that lifestyle doesn’t matter or that there is nothing outside the medical model that can help them, then they need to think seriously about finding another practitioner. Quality information and respectful and open lines of communication are much needed for both practitioner and patient, so that neither is making uninformed decisions and so that outcomes can be optimised. The Australian Senate Inquiry into the management of cancer made a number of findings and clearly indicated that the ‘cancer establishment’ should be doing a far better job in this regard.4

MIND–BODY THERAPIES

In an authoritative review, Professor David Spiegel concluded that chronic and severe depression is probably associated with an increased risk of cancer, but that there is ‘stronger evidence that depression predicts cancer progression and mortality’.5a Of all the emotional factors, depression is probably the most important.6 Further, providing psychosocial support, through a support group for example, ‘reduces depression, anxiety, and pain, and may increase survival time with cancer’.5a The longer the depression has existed, say for longer than 6 years, the greater the risk factor it is. The risk is nearly doubled, independent of other lifestyle variables, and is not related to any particular cancer.7,8 The most recent review of the effect of depression on survival for patients who already have cancer concluded that clinical depression played a causal role in cancer mortality and was associated with a 39% increased mortality rate.9

Poor coping, distress and depression have been linked to poor survival for various cancers, including cancer of liver and bile duct (hepatobiliary),10 lung cancer,11 breast cancer12, malignant melanoma13 and bowel cancer. Some studies have not confirmed a link.14 Having a good global quality of life is associated with better survival for a variety of cancers.15–18 Other factors, including the perceived aim of treatment, minimisation, quality of life and anger, all influence survival.19 Minimisation refers to a person minimising the importance or impact of the cancer. It is not denial, but reflects an ability to adapt or to see the illness in a larger perspective.

If psychological and social factors do play a role in the cause and prognosis of cancer, the important question is whether psychosocial interventions such as group support, relaxation and meditation and CBT produce better survival chances. That they can improve quality of life for cancer patients is clear, but unfortunately there are very few completed controlled trials examining the survival outcomes of such interventions. A number of studies have shown a significant improvement in both quality of life and survival time, but others have not.20

The most noted and first study of its type was done by David Spiegel, who studied women with metastatic breast cancer. His results showed a doubling of average survival time from 18.9 months to 36.6 months for the women who received the support program, compared with those who didn’t. The intervention included group support focused on improving emotional expression, some simple relaxation and self-hypnosis techniques, plus the usual medical management.21 Ten years after the study, three women in the intervention group were still alive but none in the group that had had the usual medical management alone were.

Another well-performed study by Fawzy and colleagues looked at outcomes for 68 patients with early-stage malignant melanoma.22 The patients were divided into two groups and followed for 6 years, at which time those who had had the usual surgical care and monitoring plus stress management showed a halving of the recurrence rate (7/34 vs 13/34) and much lower death rate (3/34 vs 10/34) than the group who had had the usual surgical management and monitoring alone. The intervention on this occasion was only 6 weeks of stress management. In this study, immune function was also followed. Originally the two groups were comparable but the stress management group had significantly better immune function 6 months into the study. We know that melanoma is one of the cancers that is aggressively attacked by natural killer (NK) cells and this probably contributed to the major difference in survival rates—that is, the immune system, monitoring for any cancer spread, was able to deal with it before the cancer had a chance to grow. Ten-year follow-up on the Fawzy program still shows a positive survival effect, although this has weakened a little over time,23 so it may be that people lose motivation over time, and ‘boosters’ may be required to maintain the therapeutic effect.

Other studies have also yielded promising results in terms of survival, for cancer of the liver,24 gastrointestinal tract25 and lymphoma.26 A number of trials have shown equivocal or negative results from a psychosocial support program, in terms of improved survival.27–31 One of these trials was an attempt to replicate the Spiegel study but the results showed that, despite some improvements in mental health and quality of life, there was no significant effect on survival. An even more recent study of group support for breast cancer survival showed that the intervention did not statistically significantly prolong survival, although the average survival time in the support group was 24.0 months, compared with 18.3 months in the control group. The support program did, however, help to treat and prevented new depressive disorders, reduced hopeless-helplessness and trauma symptoms, and improved social functioning.32 Another recent study on psychotherapeutic support for gastrointestinal malignancies like stomach and bowel cancer showed a clinically and statistically significant survival benefit. This hospital-based psychosocial support program was delivered to individuals rather than in a group format. Over twice the number of gastrointestinal cancer patients were alive at 10 years if they had a psychotherapeutic intervention.33 The work by the Ornish group on support programs and cancer is probably the best researched and has shown excellent results, but this included a range of other lifestyle factors apart from psychosocial support.

Support programs vary enormously in content, duration and delivery, thus many questions in the area of psychosocial support and cancer survival will need to be answered in future research.34 For example: What kinds of programs work best? Who should they be run by? How long is the optimal duration for such a program? What are the essential ingredients? What advice should a doctor give to a patient regarding whether or not to attend a support group? To what extent does compliance affect the outcome? Does having a residential component improve outcomes?

It is likely that it is not just being in a program that is protective but also the level to which a person participates in it and lives by it. This was demonstrated by one of the studies referred to above, showing that high involvement in the program was associated with better survival, and that there was no benefit from just ‘going through the motions’.35 One paper suggested that programs of 12 weeks or longer duration were more likely to be effective.36 Those that use validated forms of meditation and also foster positive emotional responses including humour and hope are more likely to be successful. Although programs attempting to deal with psychological factors need to take into account the fact that personality traits and coping styles can affect quality of survival, there are mixed results from research on whether things such as ‘helplessness’,37,38 ‘fighting spirit’ and ‘optimism’39 affect survival. Despite the fact that a number of studies suggest that they do, other studies throw this into doubt.40

If improving mental health does indeed have survival benefits, the potential mechanisms explaining that longer survival are worth considering.41 Below is a summary of key points, followed by a more extensive discussion of each.

Direct physiological and metabolic effects

Indirect effects

The original belief in psycho-oncology circles was that immune cells were the main explanation for why the mind has effects on cancer outcomes, but there is much more to it than that. Immunity may explain some of the beneficial effects of stress management for some tumours, but not all. In some cancers, such as malignant melanoma or those where viral infections are an important cause, the immune system may be the main defence, but it is probably less important for cancers that are primarily caused by chemical injury, such as lung cancer. Many cancers do not wear their mutated antigens on their surface and therefore the immune system cannot recognise and attack them.56

Some hormones can also suppress cancer growth and even induce cancer cell apoptosis. The ability to change the activity of such chemical mediators may in part explain why various activities prolong a healthy lifespan in humans, such as cognitive behaviour therapy, meditation-based therapies, stress reduction, anti-inflammatory techniques, dietary (calorie) restriction and aerobic exercise. These all affect molecular mediators including dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), interleukins and especially melatonin.57

Chronic inflammation is not a good combination with cancer. Even the inflammation associated with major surgery has been shown to increase the growth of tumour metastases at distant sites via these hormones,58 so it is important for patients with disseminated cancer only to have surgery if it is really necessary. Reducing stress hormones59 and inducing hormones associated with wellbeing and relaxation, such as melatonin, may be part of the reason that stress reduction and psychosocial interventions help cancer survival.60

Some immune mediators (e.g. TNF-alpha) can kill tumour cells and have anti-tumour effects. We now know that many tumours are ‘dormant’ through a balance between cell division, cell death and the body’s defences.61 Upsetting this balance may explain why the occurrence and recurrence of cancer often follow recent traumatic events that were not well dealt with.62 In such a case it may be more accurate to say that emotional disturbance is a contributing or precipitating factor accelerating the cancer’s growth, rather than it being the cause of the cancer.

Apart from having significant effects on immunity63 and ageing,64 melatonin also has anti-tumour effects. It slows cancer cell replication, helps to switch off cancer genes, and inhibits the release and activity of cancer growth factors, promotes better sleep and helps to enhance the immune response.65,66 Because of the biological activity of melatonin, this has a number of implications for cancer therapy.67,68 Helping the body to stimulate its own melatonin production has many beneficial effects. Among the things which stimulate melatonin endogenously are many of the interventions that are part of holistic cancer support programs (Box 24.2).

Melatonin regulates our body clock, and therefore sleep is intimately linked with melatonin levels and thereby with cancer progression.75 This may partly explain why things that affect melatonin (e.g. doing shift work or working in the airline industry) may also be risk factors for cancer.76 Body-clock alterations commonly occur in cancer patients, with greater disruption seen in more advanced cases. Emotional and social factors as well as many symptoms associated with cancer can have a significantly negative effect on sleep rhythms. From a therapeutic perspective, using behavioural interventions to enhance sleep is a vital part of coping with cancer but it also helps to improve cancer defences and prognosis. The chapter on sleep strategies (see Chapter 43) would be useful to read if sleep is a problem.

Psychological states affect genetics. We can have a genetic disposition to cancer but, equally, DNA has protective genes such as ‘cancer suppressor genes’. It has been shown that stress impairs repair of genetic mutations77 and causes oxidative damage to DNA. In experiments on workers, perceived workload, perceived stress and the ‘impossibility of alleviating stress’ were all associated with high levels of DNA damage.78,79 Personality factors were also linked to oxidative DNA damage, with high ‘tension-anxiety’, particularly for males, or ‘depression-rejection’, particularly for females, correlating with the level of DNA damage.80 A low level of closeness to parents during childhood, or bereavement in the previous 3 years, were also associated with greater DNA damage. Psychological stress reduces the ability of immune cells to initiate genetically programmed cancer cell suicide.81

Angiogenesis, which is the process of new blood vessel formation, is vital for tissue repair but also for the growth of tumours. Solid tumours can only grow into other tissues because they are able to lay down new blood vessels. Blood vessel growth is also mediated via various cytokines. One particularly important one is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and in cancer patients high levels of this cytokine are associated with poor prognosis. Sympathetic nervous system activation, a vital part of the stress response, increases the level of VEGF, and cancer patients who report higher levels of social wellbeing have lower levels of VEGF, a good prognostic sign. ‘Helplessness’ and ‘worthlessness’ are also associated with higher levels of VEGF.82 Other studies emphasising the importance of angiogenesis in tumour progression have found links with depression.83 Tumours in stressed animals showed markedly increased vascularisation (angiogenesis) and increased levels of the hormones that produce these effects.84

As ever, we are more interested in the therapeutic potential of strategies for improving psychological wellbeing. Support groups have already been discussed but other research with bearing on this topic is also of interest. A study has been performed on the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on quality of life, stress, mood, hormonal and immune function in early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients.85 The 8-week MBSR program included relaxation, meditation, gentle yoga and daily home practice, and followed patients for 12 months. The participants showed and maintained significant improvements in symptoms of stress, their cortisol levels decreased (a good prognostic sign) and physiological markers of stress reduced, as did pro-inflammatory cytokines: ‘MBSR program participation was associated with enhanced quality of life and decreased stress symptoms, altered cortisol and immune patterns consistent with less stress and mood disturbance, and decreased blood pressure’.85a

SPIRITUALITY

These are all reasons in themselves to consider ‘spirituality’, however one relates to it, as an important part of the management of cancer. Indeed, it has already been mentioned in the chapter on spirituality (Chapter 12) that approximately 80% of patients dealing with major illness wished to discuss spiritual issues with their doctor. Among cancer survivors, the relationship between social functioning and distress was significantly affected by having a sense of meaning in life, whereas the relationship between physical functioning and distress was partially mediated by meaning.86 There have been precious few studies on whether spirituality or religion is protective against cancer. The only well-performed trial found a significantly lower incidence of bowel cancer among those with a religious dimension to their lives, and this could not be explained by other risk factors.87 This study also found longer survival in those with bowel cancer.

A related issue is whether various forms of ‘distant healing’ can assist in healing or in symptom control. A review showed that there was some evidence, albeit a little sparse and inconsistent, to suggest that forms of healing including therapeutic touch, faith healing and reiki may be helpful.88 Most of the results demonstrated so far, however, are reduction in pain and anxiety, and improvement in function. Grander claims, such as effects on tumour regression through prayer, therapeutic touch and faith healing, are mainly anecdotal and have not been rigorously investigated or proved.

CONNECTEDNESS

As has been discussed, social isolation predisposes a person to a whole range of illnesses including cancer and is associated with a higher mortality rate.89 Population studies of adults demonstrated that socially isolated males were 2 to 3 times more likely to die over the following 9 to 12 years and that socially isolated women were 1.5 times as likely to die.90 This is not explained by other lifestyle factors, although our social context has a significant influence on our lifestyle. This influence can be positive or negative. Having support to give up smoking, for example, makes it much easier, whereas a lack of support can make it all but impossible.

The most common sources of social support are family and friends. It has been shown that cancer patients who are married or have a stable relationship survive for longer than would otherwise be expected. Reviews of the studies have shown an ‘association between at least one psychosocial variable and disease outcome. Parameters associated with better breast cancer prognosis are social support, marriage, and minimising and denial, while depression and constraint of emotions are associated with decreased breast cancer survival’.91

EXERCISE THERAPY

Reviewing the vast body of evidence, the World Cancer Research Fund has declared that physical inactivity is clearly a risk factor for cancer.92 This can be illustrated by examining some of the studies reviewed.

Over 30 studies have shown a protective relationship between physical activity and colon cancer mortality.93,94 This protective effect also extends to precancerous bowel polyps. The reduction of bowel cancer risk is around 50%.

Large-scale Norwegian studies show a 37% reduction in the risk of breast cancer in all women who exercise regularly, particularly in those less than 45 years of age, for whom the risk was 62% lower. In those who were lean, exercised approximately 4 hours per week and were premenopausal, the risk was reduced by 72%.95 Similar findings have been found for lung cancer.95 This is confirmed in an analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study.96 In postmenopausal women, brisk walking has been shown to reduce breast cancer risk. Another study looked at 75,000 postmenopausal women aged between 50 and 79 years, and showed that those who exercised at a level equivalent to brisk walking for 1¼ to 2½ hours per week had a significant breast cancer risk reduction of 18%.97 This increased to 22% in those who exercised up to 10 hours per week. A past history of strenuous exercise at age 35 or 50 was associated with a breast cancer risk reduction. Independent of smoking and nutritional status, the Norwegian study mentioned above also showed a reduced risk of lung cancer in those who exercised. Aerobic exercise seems to be the best protection against cancer, and the suggested reasons as to why exercise protects against cancer include:

It is very clear that cytotoxic chemotherapy only makes a minor contribution (2%) to (5-year) cancer survival. To justify the continued funding and availability of drugs used in cytotoxic chemotherapy, a rigorous evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and impact on quality of life is urgently required.102

Exercise not only helps with preventing and managing cancer, it also helps with many symptoms common among cancer patients. It is associated with reduced fatigue, greater quality of life, reduced emotional distress, improved immunological parameters, and improved aerobic capacity and muscle strength.103 It can also help with other symptoms common in cancer, such as chronic pain.104 The reduction in pain is largely due to the fact that exercise induces endorphins but is also because of its positive effects on mood, muscle relaxation and its anti-inflammatory effect, which is important for those whose pain is secondary to an inflammatory process.

NUTRITION

It is clear that what we eat contributes to our risk of developing cancer. Research is seeking to establish which foods protect and which increase risk, and how much is optimal. Overall, a poor diet increases cancer risk, probably by 30%.105,106 One point to emphasise in the information given below is that although most studies look at just one food group or one type of cancer, the same principle is likely to hold for other cancers. Although there may be some individual foods that have a particularly important role for individual cancers, as a general rule, if a food has been found to be good for one cancer it is likely to be good for other cancers as well.

Oxidation is part of the ageing process and is largely mediated by ‘free radicals’. Antioxidants help to ‘mop up’ excess free radicals and slow the ageing process. Principally, dietary antioxidants reduce cancer risk, and a healthy diet with nutritious whole food prepared in a way that preserves its nutritional value is most protective. ‘Protective elements in a cancer-preventive diet include selenium, folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin D, chlorophyll and antioxidants such as carotenoids (alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein, cryptoxanthin).’107

Although there is evidence that some antioxidant supplements, such as selenium, can have a protective effect, the best protection is gained through a healthy diet rather than taking supplements, particularly in the presence of a deficient diet. This point is illustrated by a study on breast cancer, which concluded: ‘Vegetable and, particularly, fruit consumption contributed to the decreased risk … These results indicate the importance of diet, rather than supplement use … in the reduction of breast cancer risk.’108 Antioxidant supplementation may be more helpful, particularly in helping to reduce the negative impact of radiotherapy for cancer patients.109 The chapter on genetics (Chapter 31) will also provide some useful information about nutrition, genetics, antioxidants and cancer.

Lowering total calorie intake, otherwise known as calorie restriction, helps to reduce the risk not only of cancer but also of a range of other illnesses, and significantly increases longevity. According to the World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF):

Sweet drinks such as colas and fruit squashes can also contribute to weight gain. Fruit juices, even without added sugar, are likely to have a similar effect. Try to eat lower energy-dense foods such as vegetables, fruits and whole-grains. Opt for water or unsweetened tea or coffee in place of sugary drinks.110

The WCRF also advocates a diet low in saturated fats. A trial on nearly 2500 women with breast cancer found that a low-fat diet was associated with a 24% reduction in recurrence and 19% improvement in survival after 5 years.111

The WCRF recommendation is that there is no amount of processed meat (bacon, ham, salami, corned beef and some sausages) that can be confidently shown not to increase cancer risk, particularly for bowel cancer. One should limit total intake of red meat to < 500 g cooked weight, which is equivalent to about 700–750 g raw weight, per week. Red meat probably increases the risk for a range of cancers other than bowel cancers,112 although other white meats or fish are probably less problematic. If eating meat, where possible, certified organic and free range are preferred. There are a range of hormones, antibiotics and chemicals used by many commercial meat producers that may be more problematic than is currently known.

ENVIRONMENT

Many patients who have been diagnosed with cancer will be interested in ways of altering their environment to reduce future risk for themselves and their families. There are various ways in which one’s environment can increase the risk of cancer. For example, there are five major household and environmental cancer hazards.130

THE ORNISH PROGRAM

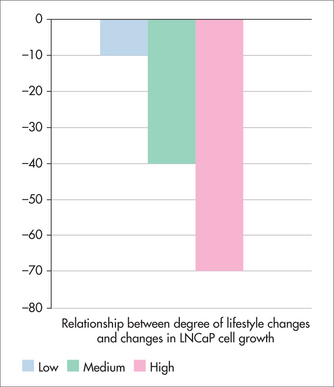

A study of men with early prostate cancer evaluated the effects, after 1 year of comprehensive lifestyle changes, on PSA and LNCaP (a marker of the body’s defences against prostate cancer).135 Eighty men with early, biopsy-proven prostate cancer who had chosen active surveillance were chosen for the study.

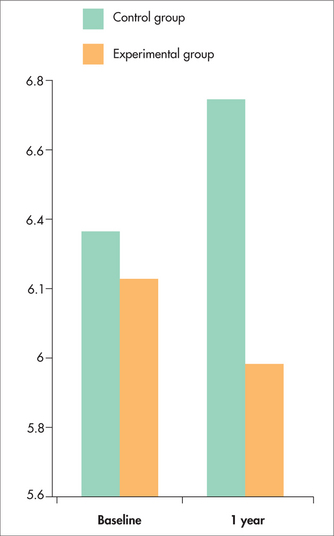

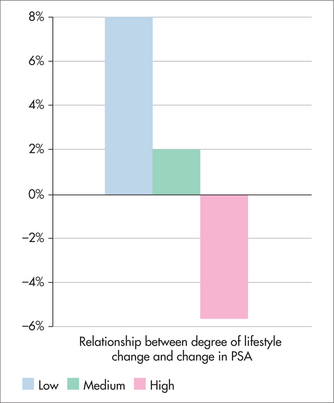

Figure 24.1 shows the average change in PSA (ng/mL) after 1 year. The average PSA of men in the Ornish group fell, unlike that of the control group. Figures 24.2 and 24.3 show that the changes in PSA and LNCaP cell growth were significantly associated with the degree of lifestyle change, meaning that the more lifestyle change the men adhered to, the greater the improvement in their condition. PSA levels decreased by an average of 4% in the experimental group but increased by an average of 6% in the control group, and growth of LNCaP prostate cancer cells was inhibited eight times more by serum from the experimental group than from the control group.

FIGURE 24.3 Relationship between degree of lifestyle change and change in prostate cancer cell growth

More recent follow-up of these programs is indicating that the improvements from making these lifestyle changes become more marked with time and is explaining more about the mechanisms whereby the improvements are produced. The lifestyle changes are associated with alterations of cancer gene expression136 and improved telomerase-based genetic repair137, both of which indicate good prognosis. This is confirmed with the findings that, at 2-year follow-up, 27% (13/49) of the patients in the control group had gone on to require aggressive cancer treatment because of disease progression, whereas only 5% (2/43) of patients in the Ornish lifestyle group had gone on to require cancer treatment because of disease progression.138

PREVENTION AND SCREENING

(See also Chapter 13, Screening and prevention)

PREVENTION: WCRF RECOMMENDATIONS

A recent statement was issued by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) following a review of decades of research into the prevention of cancer.139 The WCRF made a series of recommendations for cancer prevention. Box 24.3 is adapted from that list.

BOX 24.3 WCRF recommendations for cancer prevention3

CANCER SCREENING ACTIVITIES

Screening activities in general practice with particular relevance to cancer include:

Examination and screening tests

Waist measurement

Research by the Cancer Council Victoria involving over 40,000 subjects found a direct link between waist measurement and cancer risk.140 The results showed that being overweight or obese is associated with an increased risk of cancer of the colon, postmenopausal breast cancer and cancers of the endometrium, kidney and oesophagus. Men with a waistline over 100 cm were found to have a 72% greater risk for colon cancer and 43% for prostate cancer. For women with a waistline over 85 cm, the risk was 22% higher for breast cancer and 33% higher for colon cancer. The Cancer Council estimates that in Victoria, Australia, in 2004, 1100 cancer cases and 500 cancer deaths could be attributed to overweight and obesity.

Testicular examination

Abnormal clinical findings are followed up with Doppler ultrasound and tumour markers prior to surgical referral.

Pap smear (women)

Abnormal Pap smears need to be rigorously followed up. There is no international consensus on how women with low-grade abnormalities should be managed, and so the following is based on Australian guidelines.141

All women with atypical glandular cell reports should be referred for colposcopy.

High-risk HPV testing is used as a test of cure following treatment for CIN 2 and CIN 3.

Ovarian cancer

Current tests used in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer are the CA-125 blood test and transvaginal ultrasound. However, evidence does not support universal screening of asymptomatic women.142

Breast cancer

Even with a fully implemented mammographic screening program, more than half of all breast cancers in Australia are found by women themselves, or their doctors, as a change in the breast.143 However, the results of randomised trials do not show that a systematic approach to breast self-examination finds breast cancers early or affects survival.144 Nevertheless, breast awareness through self-examination is recommended, and women should be encouraged to present to their doctor early with any breast changes that they notice, irrespective of whether they have had recent screening mammography with normal results.145

Prostate cancer

TREATMENT

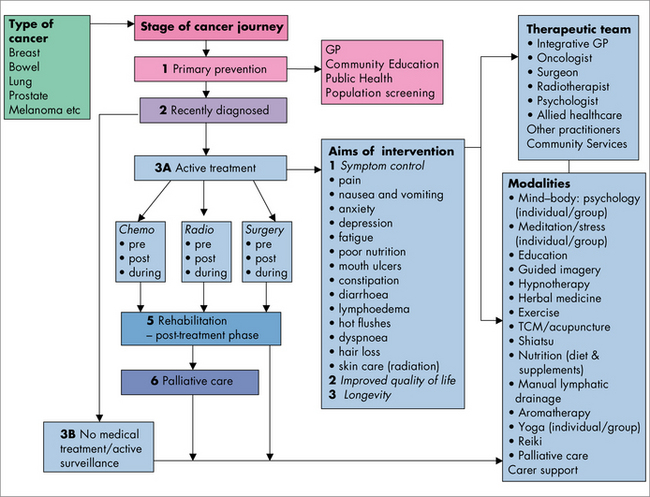

TREATMENT PLAN

Using Figure 24.4 as a decision tool, you can discuss options for what could be included in a treatment plan with the patient and their family. Beginning with the type of cancer, your decision flows to the stage of the cancer journey, and what interventions are appropriate for each stage. Where specific symptom control is required, a decision is made about the combination of treatments and the healthcare professional most appropriate to deliver those treatments.

THE THERAPEUTIC TEAM

SYMPTOMS AND SIDE EFFECTS

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Dose: metoclopramide 10 mg p.o. or IMI 1–2 hours before chemotherapy administration, then 8-hourly.

Ondansetron is usually required. It is available in IV, tablet and wafer form.

Dose: dried herb 6–15 g/day; liquid extract (1:2) 4.5–8.5 mL/day in divided doses.

ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION

Anxiety and depression are frequently associated with the diagnosis of cancer and with its treatment, and health professionals involved in care of cancer patients need to anticipate its possibility and be aware of the signs. Research shows that 20–35% of people with cancer experience ongoing depression, and 15–23% of people with cancer experience anxiety.153

Useful interventions include counselling, support groups, hypnotherapy, music therapy, meditation, stress management, acupuncture and yoga. St John’s wort may be useful for treatment of depression following treatment but care needs to be taken to check for potential interactions during chemotherapy. Significant interactions include decreased efficacy of cyclosporin, tacrolimus, irinotecan and other chemotherapeutic agents. It has also been shown to have some antineoplastic properties.154

FATIGUE

Advice on managing fatigue includes the following:

CONSTIPATION

MOUTH ULCERS

Cancer-treatment-related mouth ulcers are painful and can make it difficult to talk, breathe, eat and swallow. It might not be possible to prevent mouth ulcers, but there are some measures patients can take prior to treatment, to reduce their severity. A preventive dental check and thorough dental hygiene treatment are recommended prior to chemotherapy or radiotherapy aimed at the head and neck. Patients should be strongly encouraged to stop smoking and to eat a diet rich in fruit and vegetables. Throughout treatment, oral hygiene is essential.

Low-energy laser therapy is used in some specialised facilities to heal ulcers.

LYMPHOEDEMA

Horse chestnut standardised extract (HCSE) contains a plant compound (escin) that is well tolerated and has traditional use in strengthening the tissues of the lymph vessels, capillaries and veins.157 It may be useful in supporting treatment for lymphoedema.

Diuretic medications are not useful for this type of localised oedema.

SKIN INFLAMMATION FROM RADIOTHERAPY

Radiation dermatitis can be distressing for patients. Calendula ointment applied twice daily has been found to be superior to trolamine (a topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent) for the prevention of skin toxicity of grade 2 or higher, and for other end points including allergy, interruption of treatment, patient satisfaction, pain relief and dermatitis.158

REDUCED IMMUNE FUNCTION

Astragalus (huang-qi) is used in cancer patients to enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and reduce associated side effects. It is also used to enhance immune function. It has a wide safety margin. A Cochrane review of Chinese herbs for chemotherapy side effects in colorectal cancer patients showed that Astragalus can reduce nausea, vomiting and leucopenia.159 Increases in the proportion of T-lymphocyte subsets (CD3, CD4 and CD8) were also reported.

Baiacal skullcap may be useful as an adjunctive therapy during cancer treatment to reduce nausea and immune suppression.160

There is a potential role for Withania as an adjunctive treatment during chemotherapy for the prevention of drug-induced bone marrow suppression.161

CARDIOTOXICITY

L-carnitine is an amino acid essential for energy production in mitochondria. Long-term carnitine administration 2 g daily or b.i.d. may reduce cardiotoxic side effects of adriamycin.162

Coenzyme Q10 provides some protection against cardiotoxicity caused by some forms of chemotherapy.163,164

CHEMOTHERAPY AND RADIOTHERAPY: HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS

Herbs used with radiotherapy are listed in Box 24.4.

BOX 24.4 Herbs used with radiotherapy

National Cancer Institute. http://www.cancer.gov.

National Cancer Institute, Complementary and alternative medicine in cancer treatment, Questions and answers. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/therapy/CAM.

National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Cancer and CAM. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/cancer/camcancer.htm#top.

PubMed. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez.

World Cancer Research Fund International. http://www.wcrf.org.

1 Dy GK, Bekele L, Hanson LJ, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients enrolled onto phase 1 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(23):4810-4815.

2 Hassed C. The Essence of health: the seven pillars of wellbeing. Sydney: Random House, 2008.

3 National Cancer Institute. Staging: questions and answers; 2004. Online. Available: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/detection/staging.

4 Commonwealth of Australia, Senate Community Affairs Committee. The cancer journey: informing choice; 2005. Online. Available: http://www.aph.gov.au/SENATE/COMMITTEE/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/2004-07/cancer/report/index.htm.

5 Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):269-282. a p 269.

6 Brown KW, Levy AR, Rosberger Z, et al. Psychological distress and cancer survival: a follow-up 10 years after diagnosis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):636-643.

7 Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, et al. Chronically depressed mood and cancer risk in older persons. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(24):1888-1893.

8 Serraino D, Pezzotti P, Fratino L, et al. Chronically depressed mood and cancer risk in older persons. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(12):1080-1081.

9 Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009; 14 Sep. [Epub ahead of print].

10 Steel JL, Geller DA, Gamblin TC, et al. Depression, immunity, and survival in patients with hepatobiliary carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2397-2405.

11 Faller H, Bulzebruck H, Drings P, et al. Coping, distress, and survival among patients with lung cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(8):756-762.

12 Greer S, Morris T, Pettingale KW, et al. Psychological response to breast cancer and 15-year outcome. Lancet. 1990;1:49-50.

13 Rogentine GN, van Kammen DP, Fox BH, et al. Psychological factors in the prognosis of malignant melanoma: a prospective study. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:647-655.

14 Richardson J, Zarnegar Z, Bisno B, et al. Psychosocial status at initiation of cancer treatment and survival. JPsychosom Res. 1990;4(2):189-201.

15 Montazeri A, Gillis CR, McEwen J. Quality of life in patients with lung cancer: a review of literature from 1970 to 1995. Chest. 1998;113:467-481.

16 Coates A, Gebski V, Signorini D, et alfor the Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group. Prognostic value of quality-of-life scores during chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1833-1838.

17 Dancey J, Zee B, Osoba D, et al. Quality of life scores: an independent prognostic variable in a general population of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:151-158.

18 Coates AS, Hurny C, Peterson HF, et al. Quality-of-life scores predict outcome in metastatic but not early breast cancer. International Breast Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(22):3768-3774.

19 Butow P, Coates A, Dunn S. Psychosocial predictors of survival in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3856-3863.

20 Gottlieb BH, Wachala ED. Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):379-400.

21 Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2:888-891.

22 Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Huyn CS, et al. Malignant melanoma: effects of an early structured psychiatric intervention, coping and affective state on recurrence and survival six years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:681-689.

23 Fawzy FI, Canada AL, Fawzy NW. Malignant melanoma: effects of a brief, structured psychiatric intervention on survival and recurrence at 10-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):100-103.

24 Richardson JL, Shelton DR, Krailo M, et al. The effect of compliance with treatment on survival among patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:356-364.

25 Kuchler T, Henne-Bruns D, Rappat S, et al. Impact of psychotherapeutic support on gastrointestinal cancer patients undergoing surgery: survival results of a trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(25):322-335.

26 Ratcliffe MA, Dawson AA, Walker LG. Eysenck Personality Inventory L-scores in patients with Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Psychooncology. 1995;4:39-45.

27 Cunningham AJ, Edmonds CV, Phillips C, et al. A prospective, longitudinal study of the relationship of psychological work to duration of survival in patients with metastatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2000;9(4):323-339.

28 Edelman S, Lemon J, Bell DR, et al. Effects of group CBT on the survival time of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 1999;8(6):474-481.

29 Ilnyckyj A, Farber J, Cheang MC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychotherapeutic intervention in cancer patients. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can. 1994;27:93-96.

30 Linn MW, Linn BS, Harris R. Effects of counseling for late stage cancer patients. Cancer. 1982;49:1048-1055.

31 Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1719-1726.

32 Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: survival and psychosocial outcome from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):277-286.

33 Kuchler T, Bestmann B, Rappat S, et al. Impact of psychotherapeutic support for patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing surgery: 10-year survival results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2702-2708.

34 Fawzy FI. Psychosocial interventions for patients with cancer: what works and what doesn’t. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(11):1559-1564.

35 Cunningham A, Phillips C, Lockwood G, et al. Association of involvement in psychological self-regulation with longer survival in patients with metastatic cancer: an exploratory study. Adv Mind Body Med. 2000;16(4):276-287.

36 Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(2):179-186.

37 Visintainer MA, Volpicelli JR, Seligman ME. Tumor rejection in rats after inescapable or escapable shock. Science. 1982;216(4544):437-439.

38 Watson M, Homewood J, Haviland J, et al. Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(12):1710-1714.

39 Schulman P, Keith D, Seligman ME. Is optimism heritable? A study of twins. Behav Res Therapy. 1993;31(6):569-574.

40 Petticrew M, Bell R, Hunter D. Influence of psychological coping on survival and recurrence in people with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7372):1066.

41 Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychol. 2003;54(3):269-282.

42 Abercrombie HC, Giese-Davis J, Sephton S, et al. Flattened cortisol rhythms in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(8):1082-1092.

43 Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(12):994-1000.

44 Turner-Cobb JM, Sephton SE, Koopman C, et al. Social support and salivary cortisol in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(3):337-345.

45 Pace TW, Negi LT, Adame DD, et al. Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(1):87-98.

46 Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, et al. Can meditation slow rate of cellular aging? Cognitive stress, mindfulness, and telomeres. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1172:34-53.

47 Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Robles TF, Heffner KL, et al. Psycho-oncology and cancer: psychoneuroimmunology and cancer. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(Suppl 4):165-169.

48 Miller SC, Pandi-Perumal SR, Esquifino AI, et al. The role of melatonin in immuno-enhancement: potential application in cancer. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87(2):81-87.

49 Lissoni P. Biochemotherapy with standard chemotherapies plus the pineal hormone melatonin in the treatment of advanced solid neoplasms. Pathol Biol. 2007;55(3/4):201-204.

50 Mills E, Wu P, Seely D, et al. Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. J Pineal Res. 2005;39(4):360-366.

51 Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(6):969-981.

52 Wood PA. Connecting the dots: obesity, fatty acids and cancer. Lab Invest. 2009;89(11):1192-1194.

53 Maiti B, Kundranda MN, Spiro TP, et al. The association of metabolic syndrome with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009; 23 Oct. [Epub ahead of print].

54 Pero RW, Roush GC, Markowitz MM, et al. Oxidative stress, DNA repair, and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Detect Prev. 1990;14(5):555-561.

55 Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, et al. Classical conditioning of oxidative DNA damage in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;288(1):13-16.

56 Rabbitts J. Chromosomal translocations in human cancer. Nature. 1994;372:143.

57 Bushell WC. From molecular biology to anti-aging cognitive-behavioral practices: the pioneering research of Walter Pierpaoli on the pineal and bone marrow foreshadows the contemporary revolution in stem cell and regenerative biology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1057:28-49.

58 Oliver R. Does surgery disseminate or accelerate cancer? Lancet. 1995;346:1506.

59 Chrousos G. The HPA axis and immune mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1351.

60 Kearney R. From theory to practice: the implications of the latest psychoneuroimmunology research and how to apply them. MIH Conference Proceedings 1998;171–188.

61 Holmgren L, O’Reilly M, Folkman J, et al. Dormancy of micrometastases: balanced proliferation and apoptosis in the presence of angiogenesis suppression. Nat Med. 1995;1:149.

62 Kune S, Kune GA, Watson LF, et al. Recent life change and large bowel cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:57-68.

63 Maestroni GJ, Conti A, Pierpaoli W. Role of the pineal gland in immunity. J Neuroimmunol. 1986;13:19-30.

64 Pierpaoli W. Neuroimmunomodulation of aging. A program in the pineal gland. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;840:491-497.

65 Reiter R, Robinson J. Melatonin: your body’s natural wonder drug. Bantam Books: New York, 1995.

66 Panzer A, Viljoen M. The validity of melatonin as an oncostatic agent. J Pineal Res. 1997;22(4):184-202.

67 Coker KH. Meditation and prostate cancer: integrating a mind/body intervention with traditional therapies. Sem Urol Oncol. 1999;17(2):111-118.

68 Callaghan BD. Does the pineal gland have a role in the psychological mechanisms involved in the progression of cancer? Med Hypotheses. 2002;59(3):302-311.

69 Brzezinski A. Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:186.

70 Weindruch R, Walford RL. Dietary restriction in mice beginning at 1 year of age: effect on lifespan and spontaneous cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:986-994.

71 Heuther G. Melatonin synthesis in the GI tract and the impact on nutritional factors on circulating melatonin. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;719:146.

72 Cronin A, Keifer J, Davies M, et al. Melatonin secretion after surgery. Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1244-1245.

73 Massion AO, Teas J, Hebert JR, et al. Meditation, melatonin and breast/prostate cancer: hypothesis and preliminary data. Med Hypotheses. 1995;44(1):39-46.

74 Tooley GA, Armstrong SM, Norman TR, et al. Acute increases in night-time plasma melatonin levels following a period of meditation. Biol Psychol. 2000;53(1):69-78.

75 Sephton S, Spiegel D. Circadian disruption in cancer: a neuroendocrine–immune pathway from stress to disease? Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(5):321-328.

76 Franzese E, Nigri G. Night work as a possible risk factor for breast cancer in nurses. Correlation between the onset of tumors and alterations in blood melatonin levels. Prof Inferm. 2007;60(2):89-93.

77 Kiecolt-Glaser J, Stephens R, Lipetz P, et al. Distress and DNA repair in human lymphocytes. J Behav Med. 1985;8(4):311-320.

78 Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, et al. Relationships between perceived workload, stress and oxidative DNA damage. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74(2):153-157.

79 Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, et al. Psychological factors as a potential trigger of oxidative DNA damage in human leukocytes. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92(3):367-376.

80 Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, et al. Psychological mediation of a type of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, in peripheral blood leukocytes of non-smoking and non-drinking workers. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(2):90-96.

81 Tomei LD, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Kennedy S, et al. Psychological stress and phorbol ester inhibition of radiation-induced apoptosis in human peripheral blood leukocytes. Psychol Res. 1990;33(1):59-71.

82 Lutgendorf SK, Johnsen EL, Cooper B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and social support in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(4):808-815.

83 Onogawa S, Tanaka S, Oka S, et al. Clinical significance of angiogenesis in rectal carcinoid tumors. Oncol Rep. 2002;9(3):489-494.

84 Thaker PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med. 2006;12(8):939-944.

85 Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, et al. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):1038-1049. ap 1038.

86 Jim HS, Andersen BL. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12(3):363-381.

87 Kune G, Kune S, Watson L. Perceived religiousness is protective for colorectal cancer: data from the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:645-647.

88 Astin J, Harkness E, Ernst E. The efficacy of ‘distant healing’: a systematic review of randomised trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):903-910.

89 Pelletier K. Mind–body health: research, clinical and policy applications. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6(5):345-358.

90 House J, Landis K, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540-545.

91 Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia EA, Ioannidou EN, et al. The effect of psychosocial factors on breast cancer outcome: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(4):R44.

92 World Cancer Research Fund. Online. Available: http://www.wcrf-uk.org/cancer_prevention/index.lasso.

93 Slattery M, Potter J, Caan B, et al. Energy balance and colon cancer—beyond physical activity. Cancer Res. 1997;57:75-80.

94 Colditz G, Cannuscio C, Grazier A. Physical activity and reduced risk of colon cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:649-667.

95 Thune I, Lund E. The influence of physical activity on lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:57-62.

96 Rockhill B, Willett W, Hunter D, et al. A prospective study of recreational activity and breast cancer risk. 1999;159:2290-2296.

97 McTiernan A, Kooperburg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in post menopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative Cohort Study. JAMA. 2003;290:1331-1336.

98 Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2479-2486.

99 Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable–fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2345-2351.

100 Giovannucci EL, Liu Y, Leitzmann MF, et al. A prospective study of physical activity and incident and fatal prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):1005-1010.

101 Hall NR. Survival in colorectal cancer: impact of body mass and exercise. Gut. 2006;55:62-67.

102 Morgan G, Ward R, Barton M. The contribution of cytotoxic chemotherapy to 5-year survival in adult malignancies. Clin Oncol. 2005;16(8):549-560.

103 Galvao DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):899-909.

104 Borjesson M, Karlsson J, Mannheimer C. Relief of pain by exercise! Increased physical activity can be a part of the therapeutic program in both acute and chronic pain. Lakartidningen. 2001;98(15):1786-1791.

105 Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;66:1196-1265.

106 Key TJ, Allen NE, Spencer EA, et al. The effect of diet on risk of cancer. Lancet. 2002;360:861-868.

107 Divisi D, Di Tommaso S, Salvemini S, et al. Diet and cancer. Acta Biomed. 2006;77(2):118-123.

108 Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM, et al. Associations between breast cancer risk and the catalase genotype, fruit and vegetable consumption, and supplement use. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(10):943-952.

109 Moss RW. Do antioxidants interfere with radiation therapy for cancer? Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):281-292.

110 World Cancer Research Fund. Expert report recommendations. Online. Available: http://www.wcrf.org/research/expert_report/recommendations.php.

111 Chlebowski RT, Blackburn G, Thomson C, et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(24):1767-1776.

112 Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Moore DF, et al. Consumption of animal foods and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(9):967-988.

113 Verhoeven DTH, Goldbohm RA, van Poppel G, et al. Epidemiological studies on Brassica vegetables and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:733-748.

114 Herr I, Büchler MW. Dietary constituents of broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables: implications for prevention and therapy of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010; 19 Feb. [Epub ahead of print].

115 Brennan P, Hsu CC, Moullan N, et al. Effect of cruciferous vegetables on lung cancer in patients stratified by genetic status: a mendelian randomisation approach. Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1558-1560.

116 Conway C, Getahun S, Liebes L, et al. Disposition of glucosinolates and sulforaphane in humans after ingestion of steamed and fresh broccoli. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38(2):168-178.

117 Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable–fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2345-2351.

118 Rock CL, Flatt SW, Natarajan L. Plasma carotenoids and recurrence-free survival in women with a history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6631-6638.

119 Fleischauer AT, Arab L. Garlic and cancer: a critical review of the epidemoiological literature. J Nutr. 2001;131:1032S-1040S.

120 Madgee PJ, Rowland IR. Phyto-oestrogens, their mechanism of action: current evidence for a role in breast and prostate cancer. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:513-531.

121 Cotterchio M, Boucher BA, Manno M, et al. Dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with reduced colorectal cancer risk 1. J Nutr. 2006;136(12):3046-3053.

122 Shankar S, Ganapathy S, Srivastava RK, et al. Green tea polyphenols: biology and therapeutic implications in cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4881-4899.

123 Neto C. Cranberry and blueberry: evidence for protective effects against cancer and vascular diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):652-664.

124 Duthie S. Berry phytochemicals, genomic stability and cancer: evidence for chemoprotection at several stages in the carcinogenic process. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):665-674.

125 Larsson SC, Kumlin M, Ingelman-Sundberg M, et al. Dietary long chain ω-3 fatty acids for the prevention of cancer: a review of potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:935-945.

126 Bingham SA, Day NE, Luben R, et al. Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): an observational study. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1496-1501.

127 Meeran S, Kativar S. Cell cycle control as a basis for cancer chemoprevention through dietary agents. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2191-2202.

128 Krishnaswamy K. Traditional Indian spices and their health significance. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(Suppl 1):265-268.

129 Maskarinec G. Cancer protective properties of cocoa: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(5):573-579.

130 Kune G. Reducing the odds: a manual for the prevention of cancer. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1999.

131 Taylor R, Najafi F, Dobson A. Meta-analysis of studies of passive smoking and lung cancer: effects of study type and continent. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1048-1059.

132 Davis S, Mirick DK. Residential magnetic fields, medication use, and the risk of breast cancer. Epidemiology. 2007;18(2):266-269.

133 Henshaw DL, Reiter RJ. Do magnetic fields cause increased risk of childhood leukemia via melatonin disruption? Bioelectromagnetics. 2005;7(Suppl):S86-S97.

134 Epidemiological Study of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers (EMBRACE), Gene Etude Prospective Sein Ovaire (GENEPSO), Gen en Omgeving studie van de werkgroep Hereditiair Borstkanker Onderzoek Nederland (GEO-HEBON), International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study (IBCCS) Collaborators’ GroupAndrieu N, Easton DF, Chang-Claude J, et al. Effect of chest X-rays on the risk of breast cancer among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the international BRCA1/2 carrier cohort study: a report from the EMBRACE, GENEPSO, GEO-HEBON, and IBCCS Collaborators’ Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(21):3361-3366.

135 Ornish D, Weidner G, Fair WR, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes may affect the progression of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;174(3):1065-1069.

136 Ornish D, Magbanua MJ, Weidner G, et al. Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(24):8369-8374.

137 Ornish D, Lin J, Daubenmier J, Weidner G, et al. Increased telomerase activity and comprehensive lifestyle changes: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(11):1048-1057. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(12):1124.

138 Frattaroli J, Weidner G, Dnistrian AM, et al. Clinical events in prostate cancer lifestyle trial: results from two years of follow-up. Urology. 2008;72(6):1319-1323.

139 World Cancer Research Fund. Recommendations for cancer prevention. Online. Available: http://www.wcrf-uk.org/research_science/recommendations.lasso.

140 Cancer Council Victoria (Australia). Waistline and cancer risk. Online. Available: http://www.cancervic.org.au/preventing-cancer/weight/calculating_risk.

141 National Cervical Screening Program. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/cv-guide-article.

142 National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre. Position Statement on ovarian cancer screening. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 5 October 2009.

143 Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria. Surgical management of breast cancer in Australia in 1995. Sydney: NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre, 1999.

144 Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1445-1457.

145 Zorbas H. Breast cancer screening. Med J Aust. 2003;178(12):651-652.

146 American Urological Association. Prostate-Specific Antigen Best Practice Statement: 2009. Update. Online. Available: http://www.auanet.org/content/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines/main-reports/psa09.pdf.

147 Reindl TK, Geilen W, Hartmann R, et al. Acupuncture against chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(2):172-176.

148 Ezzo J, Vickers A, Richardson MA, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7188-7198.

149 National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health. Effect of acupuncture on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Online. Available: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/acupuncture/HealthProfessional/page6#Section_58.

150 Ryan JL, Heckler C, Dakhil SR, et al. Ginger for chemotherapy-related nausea in cancer patients: A URCC CCOP randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 644 cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl abstr 9511):15S.

151 Aung HH, Dey L, Mehendale S, et al. Scutellaria baicalensis extract decreases cisplatin-induced pica in rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52(6):453-458.

152 Taixiang W, Munro AJ, Guanjian L. Chinese medical herbs for chemotherapy side effects in colorectal cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD04540.

153 Beyond Blue. Cancer and depression/anxiety. Online. Available: http://www.beyondblue.org.au/index.aspx?link_id=4.1175.

154 Medina MA, Martinez-Poveda B, Amores-Sanchez M, et al. Hyperforin: more than an antidepressant bioactive compound? Life Sci. 2006;79(2):105-111.

155 Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Modern herbal medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2000;168-173.

156 Anderson PM, Schroeder G, Skubitz KM. Oral glutamine reduces the duration and severity of stomatitis after cytotoxic cancer chemotherapy. Cancer 19981; 83(7):1433–1439.

157 Pittler M, Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;25(1):CD003230.

158 Pommier P, Gomez F, Sunyach M, et al. Calendula ointment and radiation dermatitis during breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1447-1453.

159 Taixiang W, Munro AJ, Guanjian L. Chinese medical herbs for chemotherapy side effects in colorectal cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD04540.

160 Sagar S, Yance MN, Wong RK. Natural health products that inhibit angiogenesis: a potential source for investigational new agents to treat cancer Part 1. Curr Oncol. 2006;13(1):14-26.

161 Davis L, Kuttan G. Immunomodulatory activity of Withania somnifera extract in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71(1/2):193-200.

162 Mijares A, Lopez JR. L carnitine prevents increase in diastolic Ca2+ induced by doxorubicin in cardiac cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;425(2):117-120.

163 Bryant J, Picot J, Baxter L, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cardioprotection against the toxic effects of anthracyclines given to children with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(2):226-230.

164 Roffe L, Schmidt K, Ernst E. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 for improved tolerability of cancer treatments: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4418-4424.

165 Ladas EJ, Kroll DJ, Oberlies NH, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, pilot study of milk thistle for the treatment of hepatotoxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Cancer. 2010;116(2):506-513.

166 Ramasamy K, Agarwal R. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by silymarin. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(2):352-362.

167 Pajonk F, Reidisser A, Henke M, et al. The effects of tea extracts on proinflammatory signaling. BMC Med. 2006;4:28.

168 Kim SH, Cho CK, Yoo SY, et al. In vivo radioprotective activity of Panax ginseng and diethyl ldithiocarbamate. In Vivo. 1993;7:467-470.

169 Wang D, Weng X. Antitumor activity of extracts of Ganoderma lucidum and their protective effects on damaged HL-7702 cells induced by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2006;31(19):1618-1622.

170 Ganasoundari A, Zare SM, Uma Devi P. Modification of bone marrow radiosensitivity by medicinal plant extracts. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:599-602.

171 Pommier P, Gomez F, Sunyach MP, et al. Phase III randomized trial of Calendula officinalis compared with trolamine for the prevention of acute dermatitis during irradiation for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1447-1453.