Chapter 9 Cancer

Cancer — what is it?

Various other terms, apart from cancer, are used to describe this family of diseases that include malignancy and neoplasia. The difference between a malignant and benign tumour is summarised in Table 9.1.

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

Cancer cells are invasive and are not restricted to normal boundaries, therefore they destroy adjacent tissues. These cells survive beyond the limitations of normal cells. The telomere shortening that occurs at the end of chromosomes in normal cells is not seen in cancerous cells.1

Cancer cells can either be differentiated (Grade 1) or undifferentiated (Grade 3). In general, the differentiated cells are associated with normal immunity, whereas the undifferentiated ones are associated with poor immunity and, hence, the latter spread (metastases) more rapidly throughout the body.2

Cancer cells not only utilise lots of energy (a marked increase in glycolytic capacity) but also have a negative influence on metabolism, especially increased protein metabolism.3 Cancer cachexia, which is a loss of weight, muscle atrophy and loss of appetite, is not only due to poor intake, but also changes in metabolism.

How common is cancer?

Cancer can affect people of all ages. Over the course of a lifetime about every 1:2 males and 1:3 females in Australia and most Westernised countries will develop an invasive cancer.4, 5 The commonest cancer in males in 2005 in Australia was prostate cancer, and in females, breast cancer.4

The commonest cancers in males (in a descending order of frequency) are:

The commonest cancers in females (in a descending order of frequency) are:

The total numbers of cancers is increasing, this growth is due mainly to the ageing population.4 In males the top 5 cancers accounted for over 67% of all diagnoses, whereas in females, the top 5 cancers accounted for 63% of all diagnoses. When sexes are combined, the commonest cancer is prostate cancer.4 The 5 top cancers accounted for over 61% of all diagnoses.

The commonest internal cancers, sexes combined (in a descending order of frequency) are:

Almost all cancers occur at higher rates in males than females. The male rate is 1.4 times the female rate.4

Risk factors

In general, it is reasonable to assume that there is not 1 particular factor that is completely responsible for the cause of cancer, although 1 factor is likely to be more important than the others. It is most probable that cancer cells are formed on a regular basis, but they are destroyed when important mechanisms, such as immunity, are functioning normally and there are not excessive stimulatory hormones and other chemical insults that can destabilise immune and metabolic control.

The risk factors for cancer are:

Genetics (family history and ageing)

Most cancers are sporadic and have no strong hereditary basis. A large number of cancers have now been found to have a genetic link, but this is not the key factor leading to the development of the cancer.6 Genetic cancer research is being very actively researched with the hope of detecting those individuals who are at risk, and then being able to provide additional protection through lifestyle changes. Hopefully in the future, it may be possible to genetically engineer these genes with the aim of preventing cancer.

A number of cancers are recognised as syndromes of cancer that have a defective tumour suppressor allele.7 The following are examples: mutations in genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2 which are associated with an elevated risk of breast and ovarian cancers, and hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also known as the Lynch syndrome. Several genes are involved and include cancers of the colorectum, uterine, gastric and ovarian sites without preponderance of colorectal polyps. A range of genetic mutations and switches are activated which can initiate cancer.

Behavioural and social factors

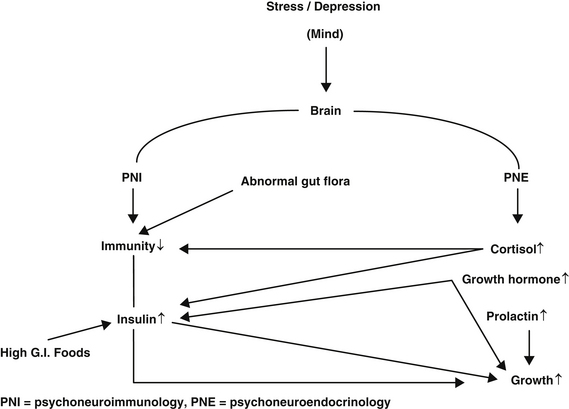

Psycho-oncology is the scientific field that describes the links between psychological and social factors with cancer. Depression is the key emotional factor that can influence immunity (psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)), as well as numerous hormones (psychoneuroendocrinology (PNE)). Depression can also influence lifestyle factors, including smoking, excess alcohol, physical activity and excess weight.8

The general overview of the key mechanisms involved in cancer are shown in Figure 9.1

An extensive review by David Spiegel concluded that chronic and severe depression is probably associated with an increased risk of developing cancer and the evidence was strong that depression predicts a poor prognosis, with more rapid progression of cancer.9 Risk of developing cancer due to depression is nearly doubled, independent of other lifestyle factors, and it is not related to any particular cancer.10, 11, 12

The longer the duration of depression the greater the risk for developing cancer.13 Depression and stress depress immunity and also increase levels of cortisol, growth hormone, prolactin and epinephrine, all of which are known to stimulate cancer growth.14–17

Insulin plus insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) have been shown in numerous epidemiological studies to be involved in increasing cancer risk.18, 19, 20 Stress can suppress natural killer cells leading to poor cancer surveillance in some cancers.21 There is increasing evidence that behaviour can influence our genes. Stress can damage DNA and impair genetic mutation repair.22, 23, 24

Personality factors, as well as sexual differences, are important relating to DNA damage.25 DNA damage is related to tension, anxiety and self-blame coping strategy in males, and in females, depression and rejection. The worst factor was the lack of subjective closeness to parents in childhood. DNA damage was also higher in subjects who had experienced the loss of a close family member within the last 3 years.

Immune cells have less ability to initiate genetically programmed cancer cell suicide with psychological stress.26 The repair of DNA is often depressed in cancer patients, which is a possible marker of cancer susceptibility.27

Shift work is associated with an increased risk of cancer which may be due to depleted melatonin levels.27 Melatonin is known to have a positive influence on immunity and also has anti-cancer effects.28, 29

Melatonin can inactivate cancer genes plus inhibits cancer growth factors.30

Inflammation and infection

Chronic inflammation is a central event that is closely associated with cancer development. Under normal circumstances, insulin has an anti-inflammatory action but this can be reversed with insulin resistance.31, 32

A recent study found that people with the highest blood levels of C-reactive protein were about 3 times more likely to develop colorectal cancer, as those with the lowest ranges.33 Elevated serum interleukin-6, which is another inflammatory marker, is also linked to cancer.34 The interesting chemo-prevention of cancer with COX-2 inhibitors is partially to do with this inflammatory process.35, 36, 37

Selective COX-2 inhibitors (Clecoxib and Rofecoxib) were used to prevent cancer with reasonable success, but withdrawn for this use because of serious side-effects.38, 39, 40

Curcumin, which is found in ginger and turmeric, is a COX-2 inhibitor and also has anti-cancer activity.41, 42 It is possible that the anti-inflammatory action of vitamin D is an important reason why it can protect from cancer.43, 44, 45 Inflammation associated with surgery can increase the size of metastases.46

Men with periodontal disease have been found to have 63% higher risk of pancreatic cancer compared to those with no sign of the disease.47 Inflammation is thought to be a key factor, but also higher levels of oral bacteria and higher levels of nitrosamines might also play a role. Other studies have shown that periodontal disease is a risk factor for other cancers.48, 49

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

Stomach cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide, and approximately half of the world’s population is infected with H. pylori.50 Conventional triple therapy is now involved with a 20% failure. In addition to being expensive, it has significant side-effects.51, 52

On a global basis, there is geographic correlation between areas with high stomach mortality rates and high prevalence of H. pylori infection.53

Studies have reported an inverse association between vitamin C intake and gastric cancer risk.54 A randomised double-blind study from China was designed to reduce the prevalence of precancerous stomach lesions. This study had 3 groups, namely 3365 eligible participants that were randomly assigned in a factorial design to 3 interventions or placebos: amoxicillin and omeprazole for 2 weeks in 1995, (H. pylori treatment); vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium for 7.3 years (vitamin supplement); and aged garlic extract and steam-distilled garlic oil for 7.3 years (garlic supplement). The study concluded that the drug treatment group showed a protective effect against pre-malignancy and malignancy. The supplement groups did not show a positive response. The authors of this study agree that the quality and doses of supplements may have been inadequate.55

There have been numerous studies using in vitro, animal and human groups dealing with H. pylori and probiotics, which have been summarised by Vitetta and Sali.56 In vitro probiotics inhibit H. pylori infection and all studies show that probiotics can reduce H. pylori gastritis and reduce the number of H. pylori.56

Seven of 9 human studies showed an improvement of H. pylori-induced gastritis and a decrease of H. pylori density following administration of probiotics.56 The addition of probiotics to standard antibiotic treatment improved H. pylori eradication and H. pylori therapy-associated side-effects.57

Olive oil polyphenols have in vitro activity against H. pylori and hence have the potential of being a chemo-preventive agent for peptic ulcer or gastric cancer.58

Viruses and cancer

Hepatitis virus B and C (HBV and HCV)

Several epidemiologic and experimental studies have established a causal role for HBV and HCV in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.50, 59, 60

Patients with cirrhosis develop nutritional deficiencies and subsequent immunologic problems. These factors could be part of the reason why these patients are at an increased risk to develop liver cancer.61 Specific nutrient deficiencies have also been found in those with liver cirrhosis such as impaired vitamin E status, reduced carotenoids and lipid soluble vitamins.62, 63, 64

Vegetable, fruit and antioxidant nutrient consumption has been found to be associated with decreased subsequent risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.65 This group found that consumption of vegetables, green-yellow and green leafy vegetables were inversely associated with the risk of hepatocellular cancer.

Curcumin has been found to inhibit hepatic fibrosis in the rodent model, and may offer protection from subsequent hepatocellular carcinoma development.66

Sho-saiko-to, a traditional Japanese herbal formula, has been shown to play a chemo-preventive role in the prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients.67

Human papilloma viruses (HPVs)

HPVs are DNA viruses that have been causally linked to cancers of the cervix and are suspected to be causally related to anal cancers and cancers of the aerodigestive tract.50, 68, 69

Apart from smoking, dietary factors appear to modulate cervical cancer.70 Women consuming low levels of vitamin C and carotenoids are at increased risk of cervical neoplasia, vitamin E and folate may also provide protection. Another study found that a diet high in folate, riboflavin, thiamine and vitamin B12 may play a protective role in cervical carcinogenesis.71 It is possible that these nutrients may help reverse cervical dysplasia.

Elevated serum homocysteine levels are strongly significantly predictive of invasive cervical cancer risk; folate, B6 and B12 are known to reduce homocysteine.72 Vegetable consumption and an increase in circulating cis-lycopene were protective against HPV persistence in another study.73

Dietary factors

It is now understood that the development of most cancers is clearly a result of an intimate interaction between endogenous and lifestyle factors, the most notable of these lifestyle factors is diet. Estimates suggest that approximately 30% of cancers are a consequence of suboptimal diet.74, 75, 76 In developing countries, the contribution of diet to cancer is estimated to be lower (20%) based mainly on higher tobacco consumption.77

Our food and drink contain mutagens and carcinogens in addition to a variety of chemicals that may be able to block carcinogenesis.78 Epidemiological investigations have been very helpful in defining the general profile of the diet which is protective: one which is low in red meat and various fats, modest in calories and alcohol, and high in fruit, vegetables and fibre. It is quite clear that a diet high in fresh fruits and vegetables is highly protective against colorectal cancer.79, 80

It is important to note that nutrition plays a role in influencing the body in many ways (e.g. immunity, behaviour) and, hence, it is likely that it plays some part in the development of all cancers, even where there is no data available. Most of the data relating to cancer and nutrition is for the more common cancers, and it is likely that a food that is good or bad for 1 cancer will be good or bad for another cancer.

Carcinogens in food

The importance of dietary acrylamide and its association with human cancers remains controversial.81, 82, 83

In 2002, Swedish scientists reported the presence of acrylamide in carbohydrate-rich foods that were produced at high temperatures, such as French fries, potato chips, breakfast cereals and toasted bread.84 Studies have shown positive dose-response relations to acrylamide exposure and cancer in multiple organs in both mice and rats.85, 86

Xenoestrogens

Xenoestrogens are defined as chemicals that mimic some structural parts of the physiological oestrogen compounds, therefore may act as oestrogens or could interfere with the actions of endogenous oestrogens. Organochlorine chemicals — pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyl compounds and other members of the Dioxin family are regarded as xenoestrogens or ‘endocrine disruptors’. These chemicals are capable of modulating hormonally unregulated processes including changes in growth factors that may be responsible for carcinogenesis, as well as congenital defects plus infertility in males.87, 88, 89

There is still controversy as to how significant the role of xenoestrogens are in humans.90

Chlorine

In population-based case-controlled studies, chlorine in water, which is the most important and the most common disinfectant, has been linked to several cancers including bladder, colorectal and possibly brain cancer.91, 92, 93 The risk is higher with more tap water that is consumed. Another group found that drinking chlorinated water disinfection by-products increased the risk of chronic myeloid leukaemia with increasing years of exposure.94

It was unusual that a protective effect was noted for chronic lymphoid leukaemia.93

Arsenic

Ingestion of inorganic arsenic from drinking water has emerged as an important factor in the cause of lung, bladder and non-melanoma skin cancers and possibly other cancers.95, 96 High levels of inorganic arsenic are found in the drinking water of many countries, including China, Argentina, Finland, Hungary and the US.95, 96

For a summary of dietary factors in cancer risk see Table 9.2.

Table 9.2 Dietary constituents reported to raise or lower the risk of cancer74, 97

| Dietary constituents in cancer | ||

|---|---|---|

Environmental factors

Air pollution

Long-term exposure to combustion-related air pollution is known to increase the risk of lung cancer, being higher in the more polluted cities.98 The cancer risks of organic hazardous air pollutants in the US have been ranked.99 Most of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, benzene, acetaldehyde and 1,3-butadiene risk was found to come from outdoor sources, whereas indoor sources were primarily responsible for chloroform, formaldehyde, and naphthalene risks.99

Electromagnetic fields (EMFs)

An advisory panel to the US and National Institutes of Science challenged a 1996 panel from the same institutes which said they found no conclusive evidence that EMFs generated by power lines and appliances were a threat to humans.100

The more recent panel found that children living near power lines appeared to have a 50% risk of leukaemia and adults had a similar increased risk of leukaemia if they were exposed to high levels of EMFs from utilities in their work places.100

A Tasmanian study has investigated residential exposure to electric transmission lines and risk of cancer.101 This case-controlled study found that there is a possibility that residents close to high voltage power lines, especially early in life, may increase the risk of myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders. Further larger, independent studies are required to be more conclusive about this issue.

In developed countries, people are constantly being irradiated from numerous sources including phones, internet, wireless, various kitchen appliances (e.g. microwave ovens and electric blankets), and it remains controversial as to whether this exposure produces adverse health effects. It is possible that EMFs may interfere with melatonin secretion.102, 103

A case-controlled study of 1700 workers employed as electricians and exposed to electric fields showed no increase in leukaemia, but there was an increase in brain tumours (no specific type), as well as colorectal cancer.104

Genetically modified foods (GM foods)

Current research in GM foods is contradictory and inconclusive, and includes much evidence showing potential health risks.105 Compass cases of adverse reactions to GM crops in humans have been recorded ranging from allergies following skin contact to an outbreak of unprecedented disease affecting thousands and dubbed eoseniamyalgia.106, 107

It is controversial whether GM crops can produce higher yields. There is also evidence showing that non-GM crops using natural matters can increase crop yield.108 There is insufficient data to do with the long-term effects of GM foods on human health.

Ionising radiation

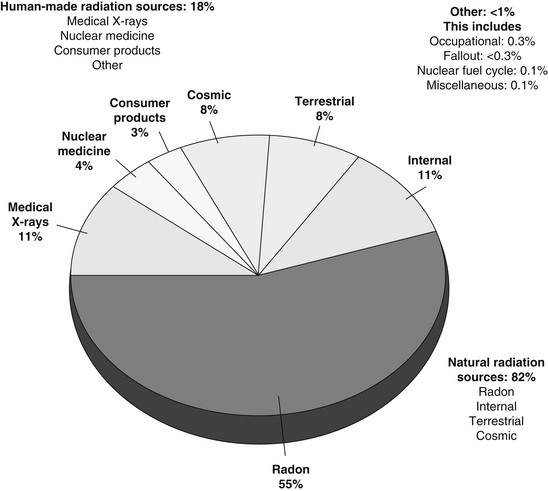

Most people are unaware that the greatest source of exposure to ionising radiation is background radiation in the environment, which constitutes 82% of all exposure (see Figure 9.2).109

Figure 9.2 Ionising radiation exposure to the public

(Source: Nasca PC, Pastides H 2008 Fundamentals of Cancer Epidemiology. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Boston)

Medical radiation is the largest source of human-made radiation and exposure is continuing to increase with time.110 X-ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis increases the risk of leukaemia, radiation for menorrhagia leads to a threefold risk of leukaemia, and radiotherapy to cancer patients has been clearly shown to increase the risk of developing secondary cancers.111, 112, 113 The thyroid is particularly sensitive to ionising radiation, especially when given to children.114

A recent retrospective study found that thyroid cancer patients with exposure to radiation from health care work places, or treatments for conditions such as breast cancer and acne, appeared to have worse outcomes than patients with the disease and no exposure.115 The use of computer tomography (CT) scans is of real concern, as studies demonstrate that radiation exposure from CT coronary angiography is a risk for cancer.116 Melbourne radiologists have called for a curb on CT scans unless completely essential.117

Toxic chemicals

Pesticides, weed–killers

It is estimated that there are about 80 000 toxic chemicals in use at present, with about 5000 used extensively.118, 119, 120

An environmental history from a patient investigates the following areas of exposure:

Some examples of toxic chemicals include dioxins and bisphenol-A (BPA).

Dioxins

A number of disorders are associated with exposure to dioxins including learning disabilities, infertility, endometriosis, immune dysfunction, endocrine disruption and carcinogen. High levels are found in large fish such as sharks, marlin and swordfish, as well as in breastmilk.120

Bisphenol–A (BPA)

Recent investigations have shown that BPA has oestrogenic activity which can lead to miscarriage, birth defects, disruption of beta cells of the pancreas, thyroid hormone disruption, liver damage plus obesity-promoting effects.121 This study also found an association of elevated urinary BPA with cardiovascular disease, diabetes and abnormal liver function tests. BPA is commonly used to line baby’s milk bottles, as well as food cans.121

Occupational exposure

Diesel exhaust fumes in trucking industry workers

Trucking industry workers who have regular exposure to diesel vehicle exhaust and other types of vehicles on highways, city streets, and loading docks have an elevated risk of lung cancer with increasing years of work.122

Exposure to pesticides

Brain tumours have been associated with several occupational and environmental exposures.123, 124, 125

Some pesticides contain alkylureas or amines that metabolise to nitroso compounds which have been associated with neurogenic tumours.126 However, a more recent study investigating exposure to pesticides and risk of adult brain tumours did not find an association between herbicide or insecticide exposure among men.123 Women with occupational exposure to herbicides had an increased risk of meningioma.123

Exposure to the styrene-butadiene rubber industry

An epidemiological study of 17 000 workers in the rubber industry found an increased risk of chronic lymphocytic and myelogenous leukaemia in the most highly exposed workers.127 Furthermore, in a study of workers involved in butadiene-monomer production, an association with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was found.128

Ethylene oxide

This chemical is used in the production of other chemicals although most human exposure occurs from its use in sterilisation of medical equipment. An increase in breast cancer occurs with a significant exposure-response relationship between ethylene oxide exposure and breast cancer incidence.129

Vinyl chloride exposure

Two large multi-centre cohort studies in facilities that manufactured vinyl chloride, polyvinyl chloride or polyvinyl chloride products showed a substantial increase in the relative risk for liver and gliosarcoma with risk increasing with duration of exposure or total exposure.130, 131

Hair dyes

Personal use of hair dyes may play a role in the risk of follicular lymphoma and chronic lymphatic leukaemia plus small lymphocytic leukaemia.132 A meta-analysis of epidemiological data has found that personal use of hair dyes is associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer.133

Cooking oil fumes

Fumes from 6 different oils: safflower, olive, coconut, mustard, vegetable and corn have been collected and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHS) were extracted from air samples.134 Fumes from safflower oil, vegetable oil and corn oil were found to have PAHS. It is thought that PAHS fumes are linked to lung cancer.

Risks to fire fighters

A review of 32 studies on fire fighters, which was to determine cancer risk using a meta-analysis, has found that there is an elevated risk of multiple myeloma.135 In addition, a probable association with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, prostate and testicular cancer was demonstrated.

Sleep patterns

Both short and long sleep duration have been associated with increased mortality from all causes for both sexes, yielding a u-shaped relationship with total mortality and a nadir at 7 hours of sleep.136 It is also of significance that usage of hypnotics is associated with an increased all-cause mortality and cause a specific mortality in regular users of hypnotics.137

It is not surprising that lack of sleep disturbance can influence mortality, as it is closely associated with stress and depression which, in turn, are linked to cancer and cardiovascular disease. Short sleep duration is also associated independently with weight gain and the latter is a risk factor for a number of cancers.138, 139, 140

Studies have found that increased sleep duration is associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer.141, 142

The frequent occurrence of disturbed sleep in cancer patients is of great concern, as many of these patients may already be suffering from fatigue due to psychological factors, chemotherapy, cancer pain or general debilitation.143 It is essential to enquire about sleep in cancer patients and to ensure that sleep disturbance is managed properly. The patient’s quality of life and their tolerance to treatment, as well as the development of mood disorders is dependent on adequate sleep.143

It is controversial whether the level of melatonin is strongly associated with the risk of breast cancer.141, 144

Exercise and cancer

Cancer prevention

The protective effect of regular exercise has been demonstrated in a number of cancers including breast, colorectal, prostate, testicular and lung cancer.145, 146, 147 There is also evidence that exercise may offer protection against endometrial, ovarian and also other forms of cancer.145, 148, 149

Exercise is known to improve immunity in the following ways:

A large study of 30 000 men found that unless they were extremely obese, cardiorespiratory fitness can abolish the risk of dying of cancer associated with being overweight.157

In the US, the surgeon general recommends 30 minutes a day of exercise most days of the week, which is generally accepted as 5 days of the week for a total of 150 minutes a week.158, 159

Resistance exercise may also be protective, as it can reduce insulin resistance in a similar way to aerobic exercise.160, 161

Cancer survival

Regular exercise can improve survival in colorectal and breast cancer patients, 50–60%.162, 163

A study of 3000 women with various stages of breast cancer were followed for 18 years and those who walked 3–5 hours per week had twice the survival than those who did not exercise.163 A further study in women with breast cancer, followed up for a period of 9 years, who exercised regularly had a 44% reduction in mortality.164 A group of 500 colorectal cancer patients were found to have half the mortality if they exercised regularly.162

In a very large prospective study of nearly 48 000 men, of the men over 65 years of age 3000 developed prostate cancer. Those who exercised regularly had reduced their chance of developing an aggressive cancer by two-thirds compared to the men who did not exercise.165

A meta-analysis of cancer survival following chemotherapy in cancer patients by Morgan and others, found that survival was improved by 2% in 5 years, which is minimal compared to the benefits of exercise.166

Exercise used during cancer treatment can counteract side-effects of disease and treatments.167 Twice weekly resistant training appears to be safe and well-tolerated, resulting in increased muscle mass and decreased body fat.168 Resistance exercise, particularly useful in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, resulted in improved quality of life and muscular fitness.160

Cancer fatigue

Exercise may also reduce fatigue resulting from chemotherapy, in cancer patients. Regular exercise can increase the fitness in breast cancer patients treated with conventional chemotherapy.169

The relative importance of cancer fatigue has been compared with other patient symptoms and concerns over 9 cancer types, and emerged as the top-rated symptom.170 To explore this issue, the author surveyed 534 patients and 91 physician experts from 5 institutions and community support agencies. It was thought by most that fatigue was attributable to both disease and treatments. Sleep disorders and difficulty falling asleep, problems maintaining sleep, poor sleep efficacy, early awakening and excessive daytime sleep are prevalent in cancer patients.171 Cancer fatigue can be modified by ensuring optimum sleep quality.172 Exercise and counselling may help to reduce fatigue.173

Overweight and obesity

The increasing incidence of obesity throughout most Western countries is said to impose a major additional cancer burden at a time when population ageing is projected to cause unprecedented growth in cancer incidence.174, 175

While obesity is frequently associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, lipids abnormalities and death from heart disease and stroke, there is growing evidence of its role in causing cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis, which included the Million Women Study, investigated the link between body mass index (BMI; calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared) and types of cancer.176, 177

In men, a 5 kg per metre squared increase in BMI was strongly associated with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus, thyroid, colon and renal cancers, and in women with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus, endometrial, gall bladder and renal cancers. There were weaker associations for melanoma and rectal cancer in men, and post-menopausal breast, thyroid and colon cancer in women. Leukaemia, myeloma and Hodgkin’s disease were associated in both sexes. Another study found higher risks of oesophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma with increasing BMI.178

It is uncertain if obesity is related to prostate cancer.179 Recent evidence suggests that obesity increases risk of advanced prostate cancer and prostate cancer mortality, but not the risk of less aggressive disease.179

Many nutritional factors are also associated with aggressive and fatal prostate cancer.196 Furthermore, greater plasma insulin-like growth factor, 1 level (IGF-1), is associated with a fivefold increased risk of advanced stage prostate cancer, but was not associated with early-stage prostate cancer.180 It is of interest that insulin receptors are present on primary human prostate cancers.181

A possible mechanism for the association of obesity and cancer is that chronic insulinaemia results in raised levels of 3 IGF-1, with higher mean concentration in men compared to women. The raised level of free IGF-1 alters the environment of cells to favour cancers developing.182

Autocrine stimulation of the growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) by IGF-22 is 1 mechanism that allows cancer cells to maintain unregulated growth and to resist program cell death (PCD).183 Obesity and type 2 diabetes are generally independently associated with an increased risk of developing cancer and a worse prognosis.184 The etiology is yet to be determined, but insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia may be important factors. Hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia and inflammatory cytokines in addition to IGFs are also possible factors involved in the process.

A study has found that patients with elevated insulin or glucose at the time of colorectal adenoma removal are at increased risk of recurrent adenoma.185 Those with an increased glucose and an increased risk for recurrence of advanced adenomas, however a systematic review meta-analysis investigating the association of glycaemic index (GI) and glycaemic load (GL) intakes with the risk of digestive tract neoplasms found that neither GI or GL intakes were associated with colorectal or pancreatic cancers.186 In contrast, results from the very large Nurses Health Study showed that high GL and insulin resistance combined to increase pancreatic cancer risk.187

It is known that diabetes diagnosed 5 or more years prior to cancer detection was associated with a twofold increasing risk of pancreatic cancer; another study found a 50% increase for diabetes diagnosed 10 or more years prior to cancer detection.188, 189 Numerous studies show that overweight individuals are consistently at high risk of pancreatic cancer compared to leaner individuals.190, 191

The association between body weight and diabetes suggests that insulin resistance may play a role in pancreatic carcinogenesis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary GI, GL and breast cancer by the same group did not provide strong support of an association between dietary GI and GL and breast cancer risk.192 Another meta-analysis found that low GI and/or low GL diets were independently associated with reduced risk for heart disease and diabetes.193

A Cochrane review demonstrated a low GI and GL diet reduced body mass and improved lipids profiles.194

In comparison, a large Swedish study of more than 60 000 women over a 20-year period found that when women were overweight they had signs of insulin resistance — such as elevated blood glucose or insulin levels, they were about 50% more likely to be diagnosed with an advanced breast cancer.195

In contrast, another meta-analysis of dietary GI, GL and endometrial plus ovarian cancer showed that a high GI, but not a high GL diet, is positively associated with a risk of endometrial cancer, particularly among obese women.190

A retrospective study found that diabetes is a significant predictor of tumour recurrence after potentially curative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma.196

Obesity appears to not be associated with prostate cancer, but studies have suggested that obese men are more likely to develop aggressive and fatal prostate cancer.197, 198 Beneficial effects of exercise in reducing colorectal, breast and prostate cancer may be through reducing hyperinsulinaemia and via IGF access.199, 200

Methological issues might explain the failure to detect differences between high and low GI diets.201 There are always difficulties in collecting accurate dietary information which would allow for the accurate calculation of GI and GL, which in turn influences the results of these studies.

Adiponectin and cancer

The mechanisms underlying malignancies are not fully understood. Adiponectin, and adipocyte secreted protein hormone is an andogenous insulin sensitiser, appears to play an important role not only in glucose and lipid metabolism, but also in the development and progression of several obesity-related malignancies.202, 203

Adiponectin is also anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory, inversely correlated with BMI, found in higher concentration in men than in women and, in some studies, its level is inversely associated with cancer risk.204 In adipocytes, androgens are converted to oestradiol, and chronic hyperinsulinaemia, also reduces sex hormone-binding globulin, leaving more oestrogen to impact on oestrogen-sensitive tissues.202, 203 Adiponectin is considered a link between obesity, insulin resistance and cancer. Levels of adiponectin are lower in obese than lean subjects.202

There is a negative relation between obesity, especially central obesity, insulin resistance and circulating adiponectin.205, 206 Adiponectin concentrations increase with weight loss, but are decreased in obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and metabolic syndrome.204, 207 Circulating levels of adiponectin are inversely associated with the risk of malignancies associated with obesity and insulin resistance.201

Cancer screening

Breast screening

In Australia the government recommends recruiting and screening women aged 50–69 years for early detection of cancer. Women aged 40–49, and 70 years and older are able to attend for screening.208

There can be differences in the results of screening when comparing different countries. A comparison of screening mammography in the US and the UK found that open surgical biopsy rates are twice as high in the US than in the UK, but the cancer detection rates were similar.209

Efforts to improve US mammographic screening should target lowering the recall rate without reducing the cancer detection rate. Recently MRI has been used to detect breast cancers that cannot be detected by mammography and ultrasonography.210

Russian equipment utilising a microwave imaging technique which detects heat at depths of 6cm may be able to detect breast cancer earlier than mammography especially in younger women with dense breasts.211,212 An advantage of this technology is that is does not involve radiation.

Early diagnosis of breast cancer is associated with better prognosis, especially when implemented with lifestyle improvements, as well as psychosocial change.213

A recent Norwegian study found that it is likely that some breast cancers detected by mammography would not persist to be detectable at the end of 6 years by mammography, raising the possibility that the natural course of some screen-detected invasive breast cancers is to spontaneously regress.214

A screening mammography can result in 33% more surgery, 20% more mastectomies and more use of radiotherapy because of over-diagnosis and others argue that the information provided to the patient about screening mammography is incomplete.215, 216 Keen and Keen, from the US, found after an extensive analysis, that less than 5% of women with screen-detectable cancers have their lives saved.217 Both of these studies are reviewed by a Lancet editorial which points out that there are problems with screening in mammography, and also that there are vested interests that make screening a business.218

Cervical screening

Cervical screening is one of the oldest and most successful forms of screening to prevent cancer. The PAP smear can detect both cervical dysplasia and carcinoma, and is now thought that about 80% of high-grade dyskaryosis and high-grade dysplasia will not progress to cancer.219

Human papilloma virus (HPV) can cause cervical cancer and the majority of the HPV involved can be eradicated by vaccination against HPV if used before being infected by the virus.220 There has been concern about the potential effect of decreased cervical cancer screening participation after HPV vaccination.221 Like most other cancers, cervical cancer is strongly associated with lifestyle factors and diet. Risk factors include unsafe sex, smoking (even second-hand smoke), being overweight and an unhealthy diet.222

The following nutrient supplements can be protective or prevent dysplasia from progressing:

The role of nutrients and cervical cancer has been summarised by Sali and Vitetta.224

It is uncertain whether particular nutrients can reduce the rate of acquisition of a high risk HPV or whether they facilitate the clearance of high risk HPV. Women with higher folate blood levels are inversely associated with a positive high risk HPV test when compared to lower folate status.228 A large case-controlled study has found that serum homocysteine was strongly and significantly predictive of cervical cancer risk.229

Chemotherapy and survival

Despite widespread optimism with the introduction of chemotherapy that it would significantly improve cancer survival, this has not been the case for the overwhelming majority. In a literature search of randomised clinical trials reporting a 5-year survival benefit attributed solely to curative and adjuvant cytotoxic chemotherapy in adult malignancies, the survival was estimated to be 2.3% in Australia and 2.1% in the US.230 Even the role of anti-angiogenic drugs, which have been shown to shrink tumours initially but can then show an unexpected surge in growth spreading both locally and to distant organs, has been disappointing.231

Chemotherapy has numerous side-effects and it is hoped that the further development of biological therapies such as the angiostatic and antibody drugs would produce better results and less side-effects. There are also concerns about the conflicts of interest in published clinical cancer research.232, 233, 234

Nearly 1 in 5 oncology articles to do with oncology research is published in prestigious journals and are funded by the pharmaceutical industry.233

Mind–body medicine

A cancer diagnosis is often life threatening to the patient. Not only do they have to deal with a grave illness, but the patient also often has to deal with toxicity related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and then they also often have to deal with difficulties following surgical procedures.235–238 Even adjuvant treatment can be given over a year and be associated with problems. There is also considerable stress for the families of the cancer patient.

Earlier in this chapter, the basic mechanisms of mind–body medicine were discussed (see Figure 9.1, page 199). It is difficult to meet the enormous emotional needs of the cancer patient. Proper care starts with the consultation. Even the words used can be important during the consultations, not just telling the patient they have ‘a cancer’ rather than ‘cancer’. The former can arouse less suspicion according to results of an Australian study.239

The psychological adaptation to cancer is influenced by various disease, demographic and psychosocial factors, including personality factors, coping abilities and social support.240 There are a number of mind–body therapies available which have predominantly evolved because of the documented negative psychosocial consequences of cancer.

Psychosocial support and mental relaxation

There are a number of modalities that have been found to benefit cancer patients including cognitive behavioural interventions, supportive psychotherapy, informational and educational treatments, social support, as well as exercise therapy, art therapy, music therapy plus other therapies. In general, it is agreed that psychosocial support for cancer patients is therapeutic.241 242

Even chatting, ideally with a confidante, helps in influencing mortality related to cancer. Research shows that 7 years after initial breast cancer treatment, a patient with 1 confidante can improve life expectancy by 15%, whereas 2 confidantes can lead to an improvement of 25%.243

Various treatment programs have also been established to help cancer patients to cope with the various psychosocial problems that are associated with this disease; programs such as the Gawler Foundation in Melbourne.244

Mental relaxation techniques

Meditation is one of the most popular and most commonly used mind–body therapies. The value of meditation and hypnosis, in the management of cancer patients, is well-documented.245, 246, 247

Meditation can reduce pain, anxiety, depression and in addition, help with sleep disturbance and fatigue.248–251

Quality of life was improved in breast and prostate cancer patients with meditation.252 The combination of mindfulness-based art therapy, which is mindfulness meditation and art therapy combined, reduced stress, distress and improved health-related quality of life.252

The benefits of mindfulness-based mood disturbance can also be maintained 6 months later, and stress reduction more than 12 months later.250, 253

Six studies have found improvement in survival and mental health8. Spiegel’s group was the first to show that psychosocial intervention over a 1-year period could improve quality of life and survival in metastatic breast cancer patients when followed up over a 10-year period.245 In another study, Fawzy was able to reduce recurrence and death in melanoma patients with a 6-week management program, and they were followed up for 6 years.246 In the Fawzy study, it was also shown that immunity improved 6 months after the 6 week management program. An improvement in survival has also been recorded with cancers of liver, gastrointestinal tract and lymphoma, plus a further study on breast cancer patients.254, 255, 256

Not all studies offering mental and social health programs have shown improved survival.8 Of these 6 studies with no improvement in survival, 3 did show improvement in quality of life. The lack of improved survival may be related to the quality of psychosocial support being offered, and whether the patient was fully involved.257, 258

Hypnosis

Breast cancer patients undergoing surgery reported less anxiety and less analgesic if they used hypnosis.259 It is likely that there would be cost reduction in the care of surgical patients who have less pain and less anxiety. Mental wellbeing was also improved with the use of hypnosis in patients undergoing radiotherapy.260

Hypnotherapy has also been beneficial for children being treated with chemotherapy; they have less nausea prior to and after chemotherapy.261

Tai chi

Tai chi is a mixture of various physical movements and synchronised breathing with meditation. The physical demands of tai chi need not be great and can be suitable for most cancer patients. A clinical trial on breast cancer patients found that tai chi performed for 60 minutes, 3 times per week, can improve quality of life and self-esteem.262 A recent study has shown that tai chi can improve immunity.263

Qigong

Qigong is a mind–body integrative exercise, or intervention, from Chinese medicine used to prevent and cure ailments, and to improve health and energy levels through regular practice.264 One study has reported decreased leukopaenia and platelet count, as well as decreased anaemia resulting from chemotherapy in the qigong group.265 Several reviews claim that qigong offers therapeutic benefits for cancer patients.266, 267, 268

Nine studies, 4 randomised and 5 non-randomised, were examined. The methodology was regarded as being poor. Two trials suggested effectiveness in prolonging life of cancer patients. The reviewers concluded that the evidence supporting qigong was incomplete based on the studies that were analysed.265

Another study showed decreased psychological distress with qigong.269

Psychological improvements occurred in an experimental group of participants after 1 month of practicing qigong.270

Reiki and/or therapeutic touch

A study on cancer patients has used an evidence-based approach to examine research regarding the effectiveness of therapeutic touch.271 This review examined 12 clinical studies involving cancer patients. All studies had experimental control groups. Eleven of the studies reported benefit from therapeutic touch.

Massage therapy

Massage can reduce pain in cancer patients.272 It has also been shown to be useful for postoperative pain.273 Massage was effective in controlling nausea in breast cancer patients.273

Biofeedback

It is possible with biofeedback to control processes that are normally voluntary. The measurements are visible on a monitor to the patient. It has been beneficial in treating cancer pain, and also helping to regain both urinary and faecal competence after surgery.274

Nutritional influences

Carotenoids

Dietary lycopene are carotenoids that are found in tomatoes and other red-coloured foods and has been shown in clinical studies to protect against cancer, including prostate, pancreas, ovary, breast, CRC and bladder cancer.279–285

Lycopene can inhibit IGF-1 in rat prostate.286 Lycopene supplement can also suppress prostate cancer growth.231

An extensive survey found that 57 of 72 studies reported an inverse association between tomato intake or blood lycopene level and cancer risk.287 Evidence for benefit was strongest for cancers of the prostate, lung and stomach. There was also benefit for pancreas, CRC, oesophagus, oral cavity, breast and cervix.

In addition to preventing cancer, vitamin A derivatives have been used to cure promyelocytic leukaemia.288

Curcumin

Curcumin is an active ingredient in the spice turmeric, and has been shown to prevent cancer and also have therapeutic properties. Curcumin can suppress tumour initiation, promotion and metastases.289

Curcumin can decrease PGE-2 substantially and this may be 1 of its actions in antagonising cancer.290 Curcumin can inhibit in vitro growth of cancers of prostate, colon and animal breast cancer.291, 292, 293

A small study using curcumin in pancreas cancer patients showed improvement in some patients.294 In animal experiments, curcumin circumvents chemo-resistance in vitro and potentiates the effect of Thalidomide and Bortezomib against multiple myeloma.295 Curcumin can inhibit the growth of cancer cells and enhances the anti-tumour effects of Gemcitabine and radiation.296 In another study, curcumin was found to sensitise ovarian and breast cancer cell lines to cisplatin through apoptotic cell death.297

Teas

Teas have protective effect against cancer, but the unfermented green tea offers the best protection with the catechins and theaflavins being the active ingredients.298

Consuming 5 or more cups of green tea a day reduced the risk of developing breast, lung, leukaemia and prostate cancer and could help reduce recurrence in breast and ovarian cancer.299–303 It is possible that tea may protect from squamous cell skin cancers also.304

In an in vitro study, tea polyphenols plus retinoic acid inhibited cervical cell growth and promoted apoptosis. Polyphenol by itself was inactive.305 A nutrient formulation which includes green tea, lysine, proline, arginine and ascorbic acid inhibits in vitro renal carcinoma growth and invasion.306, 307

A recent study found that hot tea was associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus.308 The mechanisms for this are not understood. It is controversial if milk, added to tea, can impair the bioavailability of tea catechins.309, 310

Allium vegetables

Garlic and/or onions

Garlic and onion consumption in a series of case-controlled studies have been shown to be protective against cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, oesophagus, CRC, larynx, breast, ovary, prostate and renal cell.311

Allium vegetables can suppress growth of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by causing apoptosis, and can also suppress angiogenesis.312 Another study found that garlic caused apoptosis of human glioblastoma cells in vitro.313 Garlic has been known to have anti-cancer properties because it can disrupt the action of cancer-causing agents.308, 314

Cruciferous vegetables

Cruciferous vegetables include cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, bok choy, and brussel sprouts. Although a vegetable intake has been shown to be protective against cancer, results can be inconsistent. It is thought that this inconsistency can be explained by specific sub-groups of vegetables such as the cruciferous vegetables which are more strongly related to cancer risk.315

In the Health Professional Study (HPFS), cruciferous vegetables were associated with decreased risk of bladder cancer.316 These vegetables are also protective for prostate and lung cancer.317, 318, 319

It is possible that these vegetables may decrease breast cancer risk due to the action of indole-3-carbinol which is found in cruciferous vegetables.320

The 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone plus 4-hydroxyestrone are thought to be responsible for the carcinogenic effect of oestrogen. On the other hand, the oestrogen metabolite 2-hydroxyestrone has been found to be protective against several types of cancer, including breast cancer.321 Indole-3-carbinol can increase the ratio of 2-hydroxyestrone to 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone, and also to inhibit the 4-hydroxalation of oestradiol.322

There is controversy whether microwave cooking can destroy active ingredients of the cruciferous vegetables with 1 group finding that it does, and the other finding the opposite.323, 324 It is thought that the addition of water to these vegetables at the time of microwaving may be critical.319 If cooking does influence the active ingredients in the cruciferous vegetables, this could also explain discrepancy of findings.325

Mushrooms

Medicinal properties have been attributed to mushrooms for thousands of years. Mushrooms can exert tumour-inhibitory effects by influencing T cells and macrophages, and it is thought that the glucans (lentinans) from mushrooms mediate these effects.326

Glycoproteins (lectins) present in mushrooms, broad beans, seeds and nuts have been shown in vitro experiments to increase the differentiation of cancer cells indicating that the cancer processes are either halted or reversed, as well as inhibiting cell multiplication.327 Inhibition of colon cancer and lymphoma by lentinan from shitake mushrooms has also been documented in animal experiments.328

Another mushroom (Phellinus linteus), has been shown to suppress breast, melanoma and prostate cancer growth, and also angiogenesis. The active substances are thought to be polysaccharides.329, 330 The Phellinus linteus mushroom has been found to have a synergistic effect with Doxorubicin and prostate cancer cell lines.331

Anticancer effect of Ganoderma lucidum on in vitro breast cancer cells is increased by green tea extract.332 A large case-controlled study in China revealed that high dietary intake of mushrooms decreased breast cancer risk in pre- and post-menopausal women, and there was an additional decreased risk of breast cancer from the joint effect of mushrooms and green tea.333

In vitro studies demonstrate that both mushrooms and green tea suppress invasive behaviour of cancer cells.334 Mushroom extracts increase the activity of natural killer cells in gynaecological cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.335

Polysaccharide extract of Ganoderma lucidum, when given 1800mg, 3 times daily for 12 weeks improved the natural killer cell numbers in advanced stage cancer patients.336

Polysaccharide peptides (PSP) isolated from a mushroom Coriolus versicolor significantly improved leukocyte and neutrophil count in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients with advance non-small cell lung cancer.337 Another clinical study which included patients with various cancers treated with maitake mushroom showed a significant improvement, especially in those patients with breast, lung and liver cancer.338

Soy

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated the role of soy in cancer prevention of breast, prostate, endometrium and stomach.339–342 Soy intake is most protective against breast cancer when consumed during childhood as found in a recent case-controlled study.334

Early Genistein exposure from soy promotes cell differentiation in breast tissue which suppresses the development of breast cancer in adulthood by decreasing the activity of the epidermal growth signal pathway. It has been observed that soy isoflavone Genistein induces apoptosis and inhibits growth of both androgen sensitive and androgen independent prostate cancer cells in vitro.343

The isoflavones, Genistein and Diadzein stimulate the synthesis of serum hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in the liver which results in a fall of testosterone levels.344, 345

Isoflavones can also reduce free androgens.346 A combination of soy phytochemical concentrate in green tea can reduce serum IGF and testosterone concentrations in mice.347 Soy and tea combinations have the potential of preventing breast and prostate cancers.342 Genistein can inhibit colonic cancer cells in vitro.348

Colon cancer can be hormonally influenced.349 A Japanese case-controlled study investigating the association between dietary isoflavone intake and risk of colorectal adenoma revealed a significant inverse association between dietary isoflavone intake and risk of colorectal adenoma.350

Genistein can inhibit human stomach cancer cell growth in vitro.351 Genistein has also been shown to inhibit the growth of leukaemia in vitro.352 This finding has led to the development of ipriflavone, a phenyl isoflavone, a derivative used as a treatment of leukaemia.347

Bladder cancer cells are also inhibited in vitro by soy isoflavones.353 A study from Singapore found an increased risk of bladder cancer linked to dietary soy intake.354 Consideration should be given to the chemical modification of isoflavones in soy foods during cooking and processing.355

Soy isoflavone Genistein in mouse models of melanoma has an anti-tumour and anti-angiogenic activity.356 Similar anti-angiogenic effects were obtained with soy food based diet. Another study found that soybean isoflavones reduced the experimental metastases in mice.357 Genistein has been demonstrated to be a radio-sensitiser for prostate cancer in vitro and animal experiments.358

Citrus fruits

Citrus fruits are thought to offer protection from cancer through their flavonoid content. Their high vitamin C content may also be important.359 The flavonoids can control cancer cells by suppression, blockage and transformation.354 Citrus fruits can have anti-proliferative, anti-invasive and anti-angiogenic effects.354 Citrus flavonoids have anti-proliferative effects on the following cancer cells: squamous, meningioma, leukaemia, breast, lung, melanoma and hepatoma.354

A systematic review has investigated the association between dietary intake of citrus fruits and gastric cancer risk.360 High citrus fruit intake is protective against stomach cancer. Citrus fruits have also been found to have a possible protective effect on bladder cancer.361

There is an inverse association between intake of citrus fruits and the risk of pancreatic cancer, and squamous cell oesophageal cancers.362, 363

Grapefruit

A study showed that grapefruit intake was associated with an increase in breast cancer risk and it was hypothesised that this may be mediated by an effect on oestrogen levels.364 However, the researchers were unable to examine grapefruit juice intake. An examination of grapefruit juice intake and breast cancer risk in the Nurses’ Health Study showed a significant decrease in risk of breast cancer with a greater intake of grapefruit in women.365

Interactions with various drugs

Grapefruit juice is an inhibitor of intestinal cytocrome P-453A4 system which is responsible for the first-pass metabolism of many drugs leading to elevation of their serum concentrations: in particular are its effects on the calcium channel antagonists and the statin group of drugs.366

Folic acid and cancer risk

The association with folic acid and CRC has been previously discussed. Dietary folate deficiency has also been associated with an increased risk of other cancers including prostate, breast, bladder, oral, pharyngeal, ovary, pancreas and lung cancer.367–373

It is thought that the key role of folate is that it can guard against DNA damage and promote gene stability.374

Pomegranate and ellagic acid

Pomegranate shows both antioxidant and anti-atherosclerotic properties attributed to the high content of polyphenols including ellagic acid in its free and bound forms, gallotamins and anthocyanins and other flavonoids. The most abundant of these polyphenols is punicalagin, a potent antioxidant which is hydralised to ellagic acid.375, 376

Ellagic acid, which is also found in berries and other plant foods, has been shown to exhibit anticarcinogenic properties in vitro and in animal experiments.377, 378

Pomegranate juice was found to have greater anti-proliferative action against human oral, colon and prostate tumour cells compared to purified polyphenols punicalagin and ellagic acid.379 Pomegranate juice has been found to have in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer properties against human breast cancer, human promyelocytic leukaemia cells, lung, liver, oesophageal and pancreas cancer.379, 380, 381 Ellagic acid can significantly potentiate the anti-carcinogenic potential of quercetin in vitro human leukaemia cells.382

A study on humans with rising PSA after surgery or radiotherapy for prostate cancer with a Gleeson score = /< than 7, who were treated with pomegranate juice significantly reduced the rate of PSA increase.383

Patients’ use of nutritional and herbal supplements

A growing number of the public, both young and old, are using nutritional and herbal supplements.384–389 It is therefore not surprising that cancer patients are even more likely to take supplements.390, 391, 392

Supplements are taken by cancer patients to help improve prognosis or to deal with physical or psychosocial issues and report positive responses to do with stress, depression, lack of sleep, nausea, poor immunity, pain and dyspnoea.393, 394, 395

Communication problems with medical practitioners

Due to the lack of education of medical practitioners in nutritional medicine, patients are frequently unable to receive relevant nutritional medicine information.396 Patients fear discussing issues relating to supplements because they often receive a negative response from their medical practitioner. There are a number of communication problems between the oncologist and patient. A recent study found that oncologists and thoracic surgeons rarely responded empathically to the concerns raised by patients with lung cancer.397 Empathic responses that did occur were frequently in the last third of the encounter.

Another study has also found that the oncologists encountered a few empathic opportunities and responded with empathic statements infrequently.398

Previous research has shown that the physicians responded to empathic opportunities in 38% of surgical cases, and in 15–21% of primary care cases.399, 400

Empathy is associated with improved patient satisfaction and compliance with recommended treatment.390, 401 Patients who are satisfied with their consultation, have improved understanding of their condition with less anxiety, and improved mental functioning.402

Cancer specialists also struggle if they are discussing the high costs of drugs with patients. Surprisingly, the oncologists surveyed reported the least difficulty with disclosing cancer diagnosis and being honest about the patient’s prognosis.403

A study has found that nearly all oncologists disclose to their patients that they will die, although there is a wealth of data concerning advanced-cancer patients who do not understand their prognosis.404 Fostering of hope, even in terminally ill patients, is essential.405

A cross-sectional nationwide survey was conducted with 714 (56%) members of the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia.406 Results show that Australian cancer care workers experience considerable occupational distress and regular screening for burnout is recommended.

Nutritional status of cancer patients

Malnutrition in cancer patients is common and an inverse prognostic indicator of survival with up to 80% of patients with cancer being malnourished on presentation.407, 408, 409

Malnutrition is a significant contributor to death in up to 20% of patients.410 Those that have lost weight have a poorer response to treatment, reduced quality of life and increased risk of death.411, 412 The NICE guidelines state that patients should undergo nutritional assessment.413 Unfortunately few doctors deal with malnutrition adequately.414, 415

A UK survey found that 72% of specialist oncological trainees were incapable of identifying patients with malnutrition.416 A Swedish study also found that doctors had inadequate nutritional knowledge.

Why cancer patients use complementary therapies

Complementary medicine is used to treat nausea and vomiting, fatigue, pain and other symptoms.

Anxiety, depression and fear are very common in cancer patients and can be treated effectively with complementary medicine. Most people are happy to use complementary medicine currently with conventional medicine, and not instead of it.386, 399

Nutritional supplements

Selenium / vitamin E

Selenium supplements can protect from cancer especially with CRC, lung, oesophageal, gastric and prostate cancer.417, 418 It is likely that dietary selenium is protective against breast cancer, but other studies have not supported this finding.371, 419 Selenium levels decline with age and therefore it is possible that selenium supplementation may be of benefit, in particular in the elderly.371 Selenium supplementation does not benefit nor protect basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin.420

The result of the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) and Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) studies does not support a role for vitamin E, either alone or in combination with selenium for prostate and other cancers.421, 422 A series of other studies do not support this finding.423–429

Reasons for failure of the SELECT study include the use of a vitamin E supplement that reduces gamma-tocopherol which offers major protection against prostate cancer.382, 383 The problems of using synthetic forms of vitamin E, as used in this study, have been highlighted previously. It is suggested that future supplement studies should combine alpha and gamma-tocopherol together.382 Selenium can sensitise human prostate cancer cells to TRAIL, a cytotoxic agent indicating that selenium may help overcome resistance to cytotoxic drugs.430, 431

Tamoxifen is widely used for the treatment of oestrogen-sensitive breast cancer, but the subsequent development of resistance is a key problem. Studies on breast cancer lines show that selenium synergises with Tamoxifen to improve its efficacy and help overcome resistance.432, 433

Vitamin E can reduce the risk of developing breast, lung, prostate, gastrointestinal and ovarian cancers.434, 435, 436

Vitamin E supplements may also be able to reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence among breast cancer survivors.427 Long-term use of vitamin E protected against bladder cancer.437 In animal studies, vitamin E has been shown to be protective against melanoma.438 Vitamin E analogues can induce apoptosis in malignant cell lines and inhibit tumourogenesis in vivo.439 Vitamin E analogues, epitomised by alpha-tocopherol succinate are pro-apoptotic agents with selective neoplastic activity.440, 441

Flavonoids combined with vitamin E can reduce angiogenic peptide vascular endothelial growth factor from human breast cancer cells, and the inhibitory effect was greatest from the flavonoid naringen and alpha-tocopherol succinate.442 Another major defect with these negative studies is the lack of an integrative approach which would consider behavioural, dietary, exercise and the importance of vitamin D levels.

Vitamin C

A number of case control studies have investigated the role of vitamin C in cancer prevention, and most have shown that higher intakes of dietary vitamin C are associated with decreased incidence of cancers of the mouth, throat, vocal chords, oesophagus, stomach, CRC and lung.443, 444

Combinations of vitamin C and other micronutrients generally show a positive result. Vitamin C and retinoic acid can inhibit the proliferation of human breast cancer cells by altering their gene expression.445

Lipoic acid can synergistically enhance ascorbate cytotoxicity in vitro experiments.446

Ascorbate efficacy was also enhanced in an additive fashion with vitamin K3.437

The dose of micronutrients used in this latter study could be achieved in vivo. Dietary vitamin C, E and beta-carotene have been shown to be protective against uterine cancer in a systematic literature review and meta-analysis.447 A case control study also found that dietary vitamin C and E showed an inverse association with prostate cancer incidence.448

In the double-blind placebo-controlled Women’s Antioxidant and Cardiovascular Study, women were supplemented with vitamin C, vitamin E (600IU every other day) and beta-carotene 50mg (every other day). Supplements with vitamins C, E and beta-carotene either individually or in combination did not reduce cancer incidence or reduce cancer mortality.449

The Males Physicians’ Health Study II was a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of vitamin E, 400IU (every other day) and vitamin C, 500mg daily.450

A large randomised placebo-controlled trial (SELECT) investigated the role of selenium (200mcg/day selenium methionine), and vitamin E (400IU synthetic form). Selenium or vitamin E, alone or in combination, did not prevent prostate cancer.379

In all of these randomised placebo-controlled trials, the alpha-tocopherol form of vitamin E was used. In 2 of the studies, it was the synthetic form of vitamin E, in none of these studies was gamma-tocopherol used which is the predominant form in foods.451

The doses of the type of vitamin E used in these studies are known to reduce the absorption of the gamma form of vitamin E. In SELECT, gamma-tocopherol was measured and showed nearly a 50% decline.452, 453

Gamma-tocopherol form of vitamin E is the most protective against prostate cancer.445 Hence the lowering of gamma-tocopherol in SELECT is likely to have been a factor in the lack of cancer risk reduction. In the Physicians’ Health Study, synthetic form of vitamin E was used; the natural form has proven to be better.454

When Japanese researchers gave natural and synthetic vitamin E and measured blood levels, 100mg (149IU) of natural vitamin E produced levels that required 300mg (448IU) of synthetic vitamin E to achieve.455

Most studies show that the synthetic vitamin E is only half as active in the body as the natural form.456 The doses of vitamin E used in all of these studies are inadequate and also the incorrect form is being used. It is unknown if a higher dose of vitamin C may be more protective. Vitamin C is a water-soluble vitamin, and it is more possible to maintain elevated serum levels if it is taken at least twice daily. It is not consistent with an integrative approach towards cancer prevention to be relying on 1 or 2 supplements.

Use of vitamin C for the treatment of cancer

Numerous studies have investigated the possibility of vitamin C being used in the treatment of cancer.457

Early studies by Cameron et. al., reported that it was possible to improve survival and quality of life of cancer patients using high dose intravenous vitamin C.458 Cameron was supported by Pauling to research the role of intravenous vitamin C and cancer therapy. Moertel et. al. from the Mayo Clinic reported that a high dose of oral C (10gm) was ineffective against advanced cancer.459

A clear difference in the 2 studies was the plasma concentration of vitamin C which was much lower with the oral dose. More recent studies have shown that vitamin C acts as a toxic agent against cancer cells when given intravenously. A 10gm intravenous dose of ascorbate produces plasma concentrations greater than 25-fold higher than concentrates from a similar oral dose.379

Levine’s group have shown in animal experiments that it has been possible to kill cancer cells, but not normal cells.380 These researchers have traced ascorbate’s anti-cancer effect to the formation of hydrogen peroxide in the extracellular fluid surrounding the tumours.415 They were able to significantly decrease growth rates of ovarian, pancreatic and glioblastoma established tumours. Similar pharmacological concentrations were readily achieved in humans given ascorbate intravenously.

Case reports of patients with advanced cancers have been documented. Unexpectedly long survival times after receiving high dose intravenous vitamin C therapy have been noted.460, 461

In another report, large doses of vitamin C used in combination with oral antioxidants (vitamin E, beta-carotene, coenzyme Q10 and multivitamin/ mineral complex) and chemotherapy led to patients having a positive response.462

Intravenous vitamin C for pain control

A South Korean group have investigated the effects of intravenous vitamin C on terminal cancer patients and health-related quality of life.463 All patients were given an intravenous administration of 10gm vitamin C twice with a 3-day interval and an oral intake of 4gm vitamin C daily for a week. There was a significant improvement in the quality of life after administration of vitamin C.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D plays a role in the prevention of numerous cancers including breast, CRC, prostate, pancreas, ovary, skin, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other sites.464–467

It is also known that those that live near the equator have higher vitamin D levels and are less likely to die from cancer than people in northern latitudes.468

Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the US showed that serum vitamin D deficiency exists in the US and it has major public health implications.469 Studies relating to vitamin D and cancer have been inconsistent, but researchers agree that deficiency should be prevented and vitamin D supplemented as necessary depending on blood levels.470

There is also some evidence showing that cancer survival is linked to vitamin D levels. A large study in England found that cancer survival was dependant on season of diagnosis and sunlight exposure with diagnosis in summer and autumn associated with improved survival compared to that in winter.471

Other studies have shown that exposure to sunlight was associated with reduced mortality from breast, ovarian, prostate, colon and lung cancers.466, 472, 473 Further evidence is warranted to examine the link between vitamin D and cancer incidence, survival and mortality.

Multivitamin use and risk of cancer

The role of multivitamins in isolation from an integrative approach remains controversial. In 2002, JAMA published a review supporting the role of vitamin use, especially as there are groups of patients who are at higher risk for vitamin deficiency and suboptimal vitamin status.474 Another review came to the conclusion that multivitamin and mineral supplement use may prevent cancer in individuals with poor or suboptimal nutritional status.475 It is suspected that common micronutrient deficiencies are likely to damage DNA which is likely to be a major factor in cancer development.476, 477

A Women’s Health Initiative study collected data on multivitamin use at baseline and follow-up time for a 7.9 year period.478 This study showed that multivitamin use had little or no influence on the risk of common cancers. Criticism of this study include that it was not a prospective placebo-controlled double-blind study which could avoid bias, little detail is given about the composition of the multivitamin, and there was no verification of dose taken or if the supplement was taken at all.

Individuals who used dietary supplements generally report higher dietary nutrient intakes and healthier diets, and also have healthier lifestyles.479, 480, 481

Antioxidants, vitamin E and selenium for cancer prevention

The National Prevention of Cancer Trial, recorded a 65% reduction in prostate cancer incidence in men receiving selenium supplementation.474 This study came only 2 years after the ATBC (alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene) Cancer Prevention Trial reported a 35% reduction in prostate cancer recurrence among men taking vitamin E supplementation.482

The selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT) was established to examine the effects of L-selenomethionine and racemic alpha-tocopherol acetate, alone or in combination, on the risk of prostate cancer and other health outcomes in relatively healthy men.475 This placebo-controlled study included 35 533 men (with a planned minimum follow-up of 7 years). There were 1 of 4 interventions: L-selenomethionine (200mcg/day); vitamin E placebo or racemic alpha-tocopherol acetate (400IU/day) and selenium placebo; L-selenomethionine plus or racemic alpha-tocopherol acetate or a placebo. This trial found that neither selenium nor vitamin E supplementation, alone or in combination, produced any reduction in prostate cancer or cancer of any type.

A key problem to do with SELECT or any other antioxidant supplement intervention trials is that they are not part of any integrative approach to a medical problem.405, 445 These trials are consistent with reductionist-type medicine.483

There are other problems with the SELECT study: it was expected that 75–100 prostate cancer deaths would occur, but there was only1 prostate cancer death in this trial. A major flaw of this study is also that racemic alpha-tocopherol led to decreasing gamma-tocopherol which has been found to increase the incidence of prostate cancer.382

Mega-dose supplements for bladder cancer

They were then randomised to high-dose multiple supplements (40 000IU vitamin A, 100mg vitamin B6, 2000mg vitamin C, 400IU vitamin E and 900mg zinc) or the same supplements in the recommended daily allowance (RDA).484

Additional percutaneous BCG did not influence recurrence, but it was markedly reduced in the patients receiving mega-dose of supplements after 10 months. It is possible that vitamin D could also help reduce bladder cancer, as in vitro bladder experiments with human bladder cancer cell lines show that it inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis.485

Herbal and dietary supplements during chemotherapy and radiotherapy

The role of nutritional and mineral supplements, particularly when used in conjunction with chemotherapy and radiation therapy, is an issue of considerable controversy.486–491

A study of lung cancer patients with supplements — vitamin C, vitamin E and beta-carotene — did not show interference with the effectiveness of chemotherapy.492 There was a better response and survival in those who received the supplement although the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Breast cancer patients were treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus folic acid. It was possible to improve 5-FU effectiveness.493 Survival in the group receiving 5-FU plus folic acid was 47% greater than the group receiving 5-FU alone.

Two prescription antioxidants, amifostine and dexrazoxane, have been used concurrently with chemotherapy and radiotherapy.491

According to 29 studies, amifostine reduces side-effects and increases response rates of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. In 21 studies, dexrazoxane has been shown to protect the heart from Adriamycin toxicity without interfering with anti-tumour effect by chelating iron that would otherwise form free radicals.491

Common nutrient deficiencies in cancer patients include folic acid, vitamin C, pyridoxine and other nutrients.494 Chemotherapy and radiotherapy reduce serum levels of antioxidants, vitamins and minerals due to lipid peroxidation and fast produce higher levels of oxidative stress.491–499

Fifty human studies using either single or multiple nutrients in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment found that nutrients do not interfere with treatment.500–502 Side-effects were decreased in 47 of these 50 studies, and the other 3 studies showed no differences.