Chapter 2 Canalplasty for Exostoses of the External Auditory Canal and Miscellaneous Auditory Canal Problems

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The etiology of these benign growths of the tympanic bone is strongly associated with the frequency and severity of exposure to cold water.1 Frequently, these lesions are found in surfers, swimmers, or other individuals with frequent cold water exposure over several years. A widely held belief based on clinical information is that exostoses occur primarily during the years of growth, with their proliferation being enhanced or perhaps even caused by exposure to cold water during this period. This belief tends to be supported by historical information from patients with exostoses, who almost always indicate that they swam in cold water during their youth.2–4 This historical information is strongly corroborated by the high incidence of exostoses in avid surfers who spend hours in the water almost daily. In our clinical experience, this problem occurs almost exclusively in men, who are more likely than women of the same age to have had frequent cold water exposure during their youth.

EXOSTOSES OF THE EXTERNAL AUDITORY CANAL

Preoperative Preparation

Site Preparation

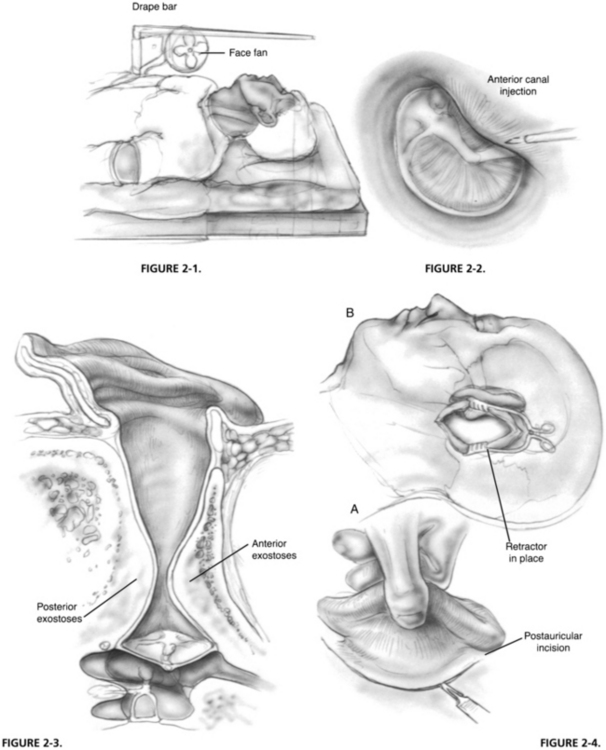

The hair is shaved behind the ear to a distance of approximately 1.5 inches posterior to the postauricular fold. The auricle and the periauricular and postauricular areas are scrubbed with povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution or chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) for iodine-allergic patients. A plastic drape is placed over the area with the auricle and the postauricular area exteriorized through the opening in the drape. This drape is placed over an L-shaped bar that is fixed in the rail attachment of the operating table (Fig. 2-1). For patients under local anesthesia with sedation, a small, low-volume office fan is attached to the bar to provide a gentle cooling breeze to the patient’s face during the procedure. The plastic drape forms a canopy, allowing the patient to see from under the drape and reducing the feeling of claustrophobia. In addition, a foam earpiece from an insert speaker is put into the opposite ear. The earpiece is connected to a compact disk player and input microphone that allows the patient to listen to relaxing music and provides a pathway to converse with the patient, if desired.

Analgesia

It is important not only to achieve analgesia, but also to maximize canal hemostasis with injections into the external auditory meatus. Using 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine) with 1:20,000 epinephrine solution in a ringed syringe with a 27 gauge needle, a classic quadratic injection is made such that each injection falls within the wheal of the previous injection. Another useful injection is an anterior canal injection, which is made with the bevel of the needle parallel to the bony wall of the external meatus (Fig. 2-2). In a patient with extensive exostoses, this injection is usually made into the lateral base of a large anterior sessile osteoma. After insinuation of the needle, it is advanced a few millimeters, and a few drops are injected extremely slowly. The solution infiltrates medially along the anterior canal wall and provides some analgesia to the auriculotemporal branch of CN V, which is usually unaffected by the quadratic injection and adds to the hemostasis anteriorly. The postauricular area is infiltrated with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine solution mixed with equal parts of 0.5% bupivacaine.

Surgical Technique

Most surgical approaches for removal of EAC exostoses are through the transmeatal route.5–7 This approach has two disadvantages. It usually results in significant loss of the remaining canal wall skin through damage by the drill, and it does not allow adequate visibility or instrument and drill access to remove the medial portion of the exostotic mass near the tympanic membrane safely. A large sessile anterior exostosis is almost uniformly present in these patients (Fig. 2-3). The approach described here is primarily postauricular and one that maximizes conservation of the canal wall skin and facilitates careful removal of the anterior exostosis, which is usually extremely close to the tympanic membrane.

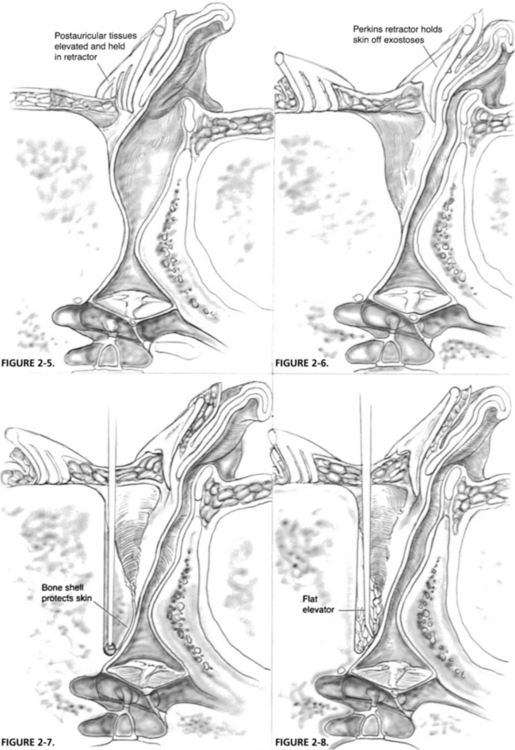

A curvilinear postauricular incision is made approximately 1 cm behind the postauricular fold (Fig. 2-4). The skin and subcutaneous tissues are elevated anteriorly to the area of the spine of Henle and the bony posterior canal, and a toothed, self-retaining retractor is placed (Fig. 2-5). Locating this area is facilitated by finding the plane of the lateral surface of the inferior border of the temporalis muscle and dissecting in this plane anteriorly to reach the meatus. When this area is reached, the skin overlying the lateral slope of the posterior exostosis is elevated from its surface, and a Perkins bladed tympanoplasty retractor is inserted to hold elevated skin off the surface of the lateral portion of the bony mass (Fig. 2-6).

Removal of Posterior Exostosis

By use of a medium-sized cutting burr and an appropriately scaled suction-irrigator, the posterior exostosis is entered along its lateral sloping edge, and the bony removal is progressed medially, keeping a shell of bone over the area being burred anteriorly (Fig. 2-7). The remaining skin over the exostosis medial to the skin elevated earlier is protected from the burr. As this shell becomes thinner, it is advisable to switch to a diamond burr to prevent a sudden breakthrough to the skin, which might occur if one continues with the cutting burr on the excessively thinned bone. The bone removal is continued medially and posteriorly until the estimated normal posterior canal contour and dimension is achieved. As one approaches a medial depth consistent with the posterior annulus of the tympanic membrane (which usually cannot be seen directly at this point), care must be taken to avoid damage to the chorda tympani nerve and the posterior aspect of the tympanic membrane. The surgeon should also keep in mind that some patients’ facial nerve exists lateral to the tympanic annulus at its posteroinferior border. Facial nerve monitoring reduces the possibility of injury to the nerve in a patient unable to tolerate local anesthesia. The thinned bony shell is collapsed, and a small elevator reveals the inside surface of the posterior canal skin that was over the exostosis (Fig. 2-8).

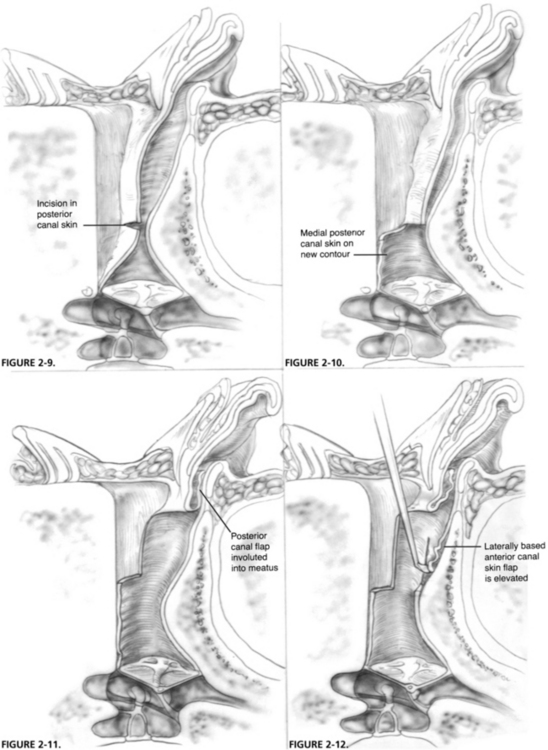

An incision is made midway along the posterior canal skin perpendicular to the long axis of the EAC (Fig. 2-9). The posterior canal skin medial to this incision is positioned onto the new contour of the posterior canal wall (Fig. 2-10). The transmeatal approach is then taken, and incisions are made with a sickle knife superiorly and inferiorly in the canal, extending from the ends of this previous incision laterally to the meatus, and creating a laterally based posterior canal skin flap. This flap is involuted back into the meatal portion of the canal and held there with the Perkins retractor (Fig. 2-11). Attention is turned to the anterior exostosis, which has now been revealed.

Removal of Anterior Exostosis

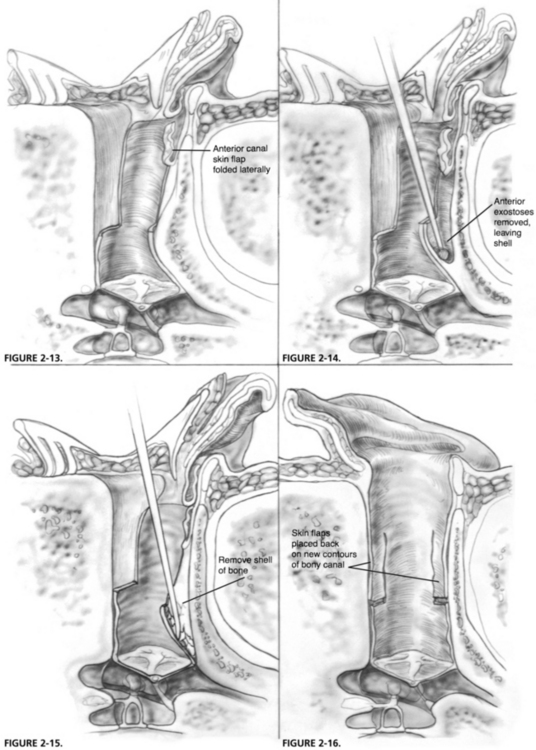

By use of a round knife, an incision is made in the skin overlying the anterior exostosis from superior to inferior over the dome of the exostosis and as far medially as can be seen. This incision is connected to the incisions previously made superiorly and inferiorly in the canal that defined the posterior canal skin flap, and this anterior canal flap is elevated laterally (Fig. 2-12). Frequently, the skin of the vascular strip can be left intact if the exostoses do not involve this portion of the canal. By use of a back-angled Perkins tympanoplasty elevator, this laterally based anterior canal skin flap is elevated further to the cartilaginous portion of the anterior canal and is smoothed so as to lie laterally near the posterior canal flap under the retractor (Fig. 2-13).

With a cutting burr and small suction-irrigator, the anterior exostosis is removed in a manner similar to that of the posterior one, and a thin shell of bone that protects the canal skin is left over the anteromedial portion of the exostosis from the burr (Fig. 2-14). This bone removal is continued to the area of the anterior annulus of the tympanic membrane. The bony shell is collapsed and removed, leaving the intact anterior canal skin (Fig. 2-15). Usually, it is necessary to finish up and smooth an edge of bone that remains at the anterior extent of this dissection to have a smooth contour near the annulus area. To protect the elevated anterior sulcus skin from the burr, a small tympanic membrane–sized piece of silicone elastomer (Silastic) or suture packet foil is placed on the inside surface of the anterior canal skin to hold it against the tympanic membrane during drilling. This prevents the skin flap from getting involved with the burr, and prevents damage to the tympanic membrane that might occur with the burr being used in such close proximity to the membrane. Subsequently, the Silastic is removed, the medial anterior canal skin is placed on the bone, and all skin flaps are folded back into position on the new contours of the bony canal (Fig. 2-16). The medial flaps are packed into place with chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin)-soaked absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) pledgets, and the postauricular incision is closed with interrupted subcuticular 4-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) suture.

MISCELLANEOUS EXTERNAL AUDITORY CANAL CONDITIONS

Medial Third Stenosis

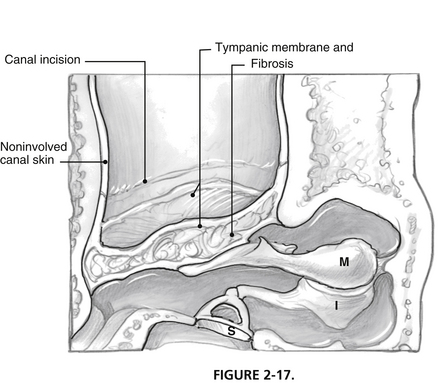

Surgical repair may be necessary when conductive hearing loss produces a functionally significant deficit for the patient. Successful repair is frequently possible, although restenosis may occur, and this possibility should be included in the informed consent. Technically, a postauricular approach is used to allow complete resection of the fibrotic segment medial to noninvolved EAC skin where an incision has been previously created working through a transcanal route (Fig. 2-17). Removal of most of the fibrous layer of the tympanic membrane seems to reduce the chance of postoperative restenosis. Tympanoplasty is performed with a lateral graft or fasciaform technique. Coverage of the resultant exposed bone is mandatory and is provided with a free split-thickness skin graft. The posterior surface of the pinna provides skin of appropriate character within the operative field and can be taken with a No. 10 blade. Skin grafts should overlap the fascia used for tympanic membrane replacement, but should not extend to cover the lateral surface of the reconstructed drum.

Keratosis Obturans

Exuberant accumulation of desquamated skin may produce bony erosion and gradual expansion of the bony EAC.8 The process may progress to the point of erosion into structures adjacent to the canal, such as the temporomandibular joint or mastoid. Erosion lateral to the eardrum may cause loss of support of the fibrous annulus of the tympanic membrane and a characteristic “jump rope sign” inferiorly (which can also be seen after curetting for a stapes procedure more superiorly). Poor epithelial migration has been proposed as the cause of the disorder. Frequent cleaning may retard the process. Cleaning may be much easier if the typically inspissated and adherent material is softened with mineral oil for several days before the clinical appointment. Surgical intervention is rarely indicated, unless severe erosion exposes vital structures.

Scutum Defects

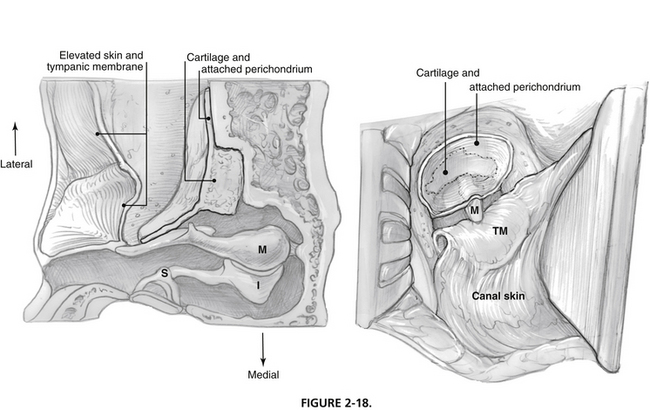

Cartilaginous repair is possible with cartilage harvested from the base of the tragus. The perichondrium is left attached to one side of the cartilage, which is carved to match the bony defect similar to the piece of a puzzle. The composite graft is inserted in the defect after elevation of the canal skin and eardrum from the lateral surface of the handle of the malleus. The graft is positioned such that the perichondrium faces the elevated skin and eardrum, and the cartilage extends into the defect (Fig. 2-18).

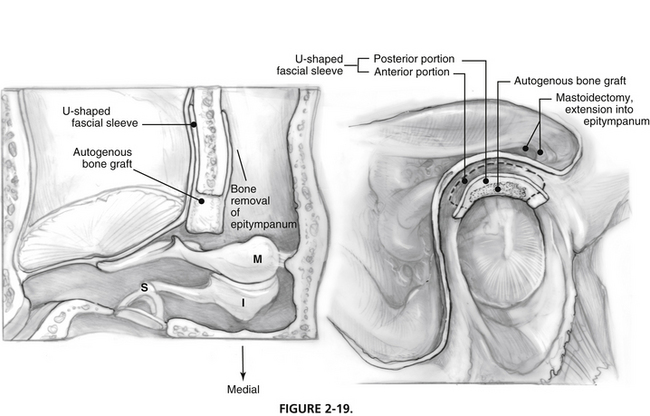

Alternatively, bone formation may be stimulated with placement of autogenous bone chips (bone pâté harvested with a microdrill and mixed with antibiotic) within a U-shaped fascial sleeve.9 This technique requires removal of bone lateral to the heads of the ossicles in the epitympanum and sculpting of the posterior surface of the bony external canal to allow placement of the fascia (Fig. 2-19).

1. Kroon D.F., Lawson M.L., Derkay C.S., et al. Surfer’s ear: External auditory exostoses are more prevalent in cold water surfers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:499-504.

2. Adams W. The aetiology of swimmer’s exostoses of the external auditory canals and of associated changes in hearing: I. J Laryngol. 1951;65:133-153.

3. Harrison D. Exostosis of the external auditory meatus. J Laryngol. 1951;65:704-714.

4. Fowler E.P.Jr., Osmun P.M. New bone growth due to cold water in the ears. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1942;36:455-466.

5. Rauch S.D. Management of soft tissue and osseous stenosis of the ear canal and canalplasty. In: Nadol J.B.Jr., Schuknecht H.F., editors. Surgery of the Ear and Temporal Bone. New York: Raven Press; 1993:117-125.

6. Shambaugh G.E.Jr., Glasscock M.E.III. Operations on the auricle, external meatus, and tympanic membrane. In: Shambaugh G.E.Jr., Glasscock M.E.III, editors. Surgery of the Ear. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1980:194-215.

7. Dibartolomeo J.R. Exostoses of the external auditory canal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88(Suppl 61):2-20.

8. Piepergerdes J.C., Kramer B.M., Behnke E.E. Keratosis obturans and external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:383-390.

9. Althaus S.R. Tympanomastoid surgery: A technique for repairing posterior osseous canal wall defects with autologous temporalis fascia and bone pâté. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:529-535.