Chapter 14 Canal Wall Reconstruction Tympanomastoidectomy

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The primary goal in the surgical management of chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma is the creation of a dry, safe ear through removal of disease and the alteration of anatomy to prevent recurrence. This goal can be accomplished effectively with preservation (canal wall up) or removal (canal wall down) of the posterior canal wall, both of which are described in other chapters 16 and 17. This chapter describes the technique of canal wall reconstruction tympanomastoidectomy with mastoid obliteration. Canal wall reconstruction tympanomastoidectomy combines elements of the canal wall up and canal wall down procedures to optimize surgical exposure for removal of disease, and creates a blockage of the attic that prevents recurrence of retraction pockets and recurrence of cholesteatoma.

Many authors have described reconstruction of the posterior canal wall and mastoid obliteration using various methods, including composite osteoperiosteal flaps,1 composite cartilage/titanium grafts,2 ceramic alloplasts,3–7 bone pâté,8–10 costal cartilage,11 and bone cements.12–14 Canal wall reconstruction tympanomastoidectomy with mastoid obliteration was originally described by Mercke in 1987.15 Important modifications to the Mercke technique have been have been published by the senior author16 and are described in detail in this chapter.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF CANAL WALL UP AND CANAL WALL DOWN TECHNIQUES

Canal wall down tympanomastoidectomy is the gold standard for surgical management of cholesteatoma.17,18 The enhanced exposure to the attic, antrum, and middle ear afforded by removal of the posterior canal wall provides for optimal visualization and removal of disease in cases of extensive cholesteatoma. Removal of the canal wall and lateral attic also prevents retraction and recurrent cholesteatoma formation. In addition, all nitrogen-absorbing mucosa of the mastoid cavity and epitympanum is removed, and ultimately is replaced by stratified squamous epithelium after healing has occurred. When performed properly, the canal wall down procedure can result in a recidivism rate of 2%.17

Preservation of the posterior canal wall in cholesteatoma surgery has many advantages, including the elimination of the need for periodic cleaning and avoiding the need for water restrictions. The recidivism rate has been reported to be 36% in adults and 67% in children,19 however, higher by many reports than the incidence of recurrent disease seen with canal wall down procedures.18,20 The high rate of recidivism seen in canal wall up procedures can be due to numerous factors. First, exposure of the attic, antrum, and facial recess is more limited in canal wall up procedures compared with canal wall down approaches, which may lead to difficulty in complete removal of all involved air cell tracts and elimination of cholesteatoma at the initial procedure. Second, the epitympanum and mastoid cavity are ultimately relined with nitrogen-absorbing cuboidal mucosal epithelium after canal wall up procedures. The presence of this nitrogen-absorbing mucosa is thought to lead to negative middle ear and mastoid pressures, especially when continued inflammation with associated hypervascularity affects the mucosal layer.21 This large surface area of nitrogen-absorbing epithelium along with underlying eustachian tube dysfunction can lead to progressive retraction of the tympanic membrane postoperatively, and ultimately to recurrence of cholesteatoma.16 Eustachian tube dysfunction exacerbates this scenario in children.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Mastoidectomy: Special Considerations

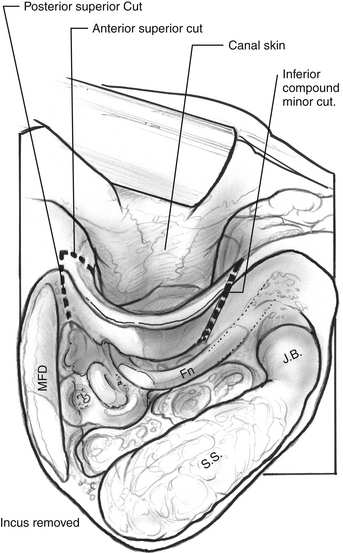

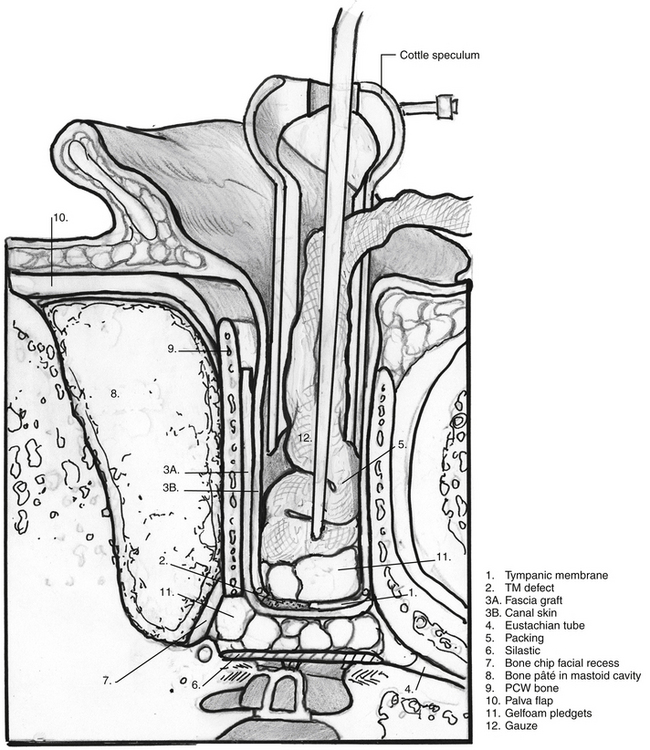

An intact canal wall mastoidectomy and facial recess are performed as described in Chapter 16. Care is taken to maintain adequate posterior canal wall bone thickness and to avoid lowering (medializing) the lateral portion of the bony canal, both of which aid in the canal wall reconstruction to come. Cholesteatoma that is encountered in the mastoid or facial recess is removed as exenteration of air cells in these areas progresses. Meticulous removal of all air cells in the sinodural angle, mastoid tip, and retrofacial areas is crucial. The facial recess is opened widely and extended inferior to the floor of the EAC. The incus is removed, as is the head of the malleus. The skin of the posterior, inferior, and superior EAC is elevated off the underlying bone without any prior canal skin incisions (Fig. 14-1). The annulus is elevated, and the tensor tympani tendon is cut allowing the tympanic membrane and canal skin to be reflected anteriorly as a sleeve. The tympanic membrane remnant is separated from the neck of the cholesteatoma sac in this process.

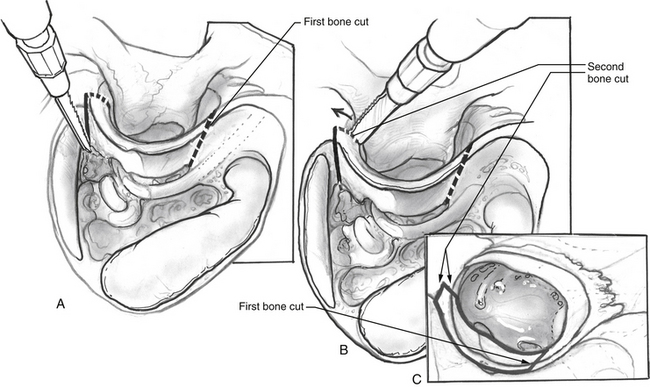

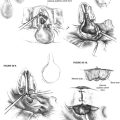

A microsagittal saw (Anspach, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, or Jed Med Bien Air, St Louis, MO) is used under continuous irrigation to create superior and inferior cuts in the posterior canal wall. The cuts are performed in a locking fashion to help prevent collapse of the canal into the mastoid after reconstruction (see Fig. 14-1). Superiorly, two cuts are made. The first is parallel to the temporal lobe in a posterior-to-anterior direction (Fig. 14-2A). The second cut is perpendicular to the first, made from the superior external canal to meet the posterosuperior cut at a right angle (Fig. 14-2B). The inferior cut extends from the inferior facial recess laterally, widening and beveling as a compound miter (Fig. 14-2C). It is important to bevel the cut from medial to lateral and posterior to anterior so that when the canal wall is replaced, it does not fall back into the mastoid when the canal wall skin is packed back into place.

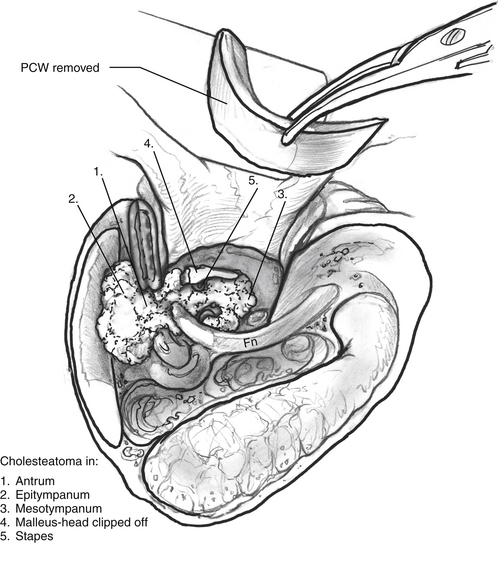

The posterior canal wall segment is removed, and the medial portion is inspected (Fig. 14-3). Any adherent squamous epithelium is removed with a diamond drill or gauze sponge. The posterior canal wall is placed aside for future reconstruction.

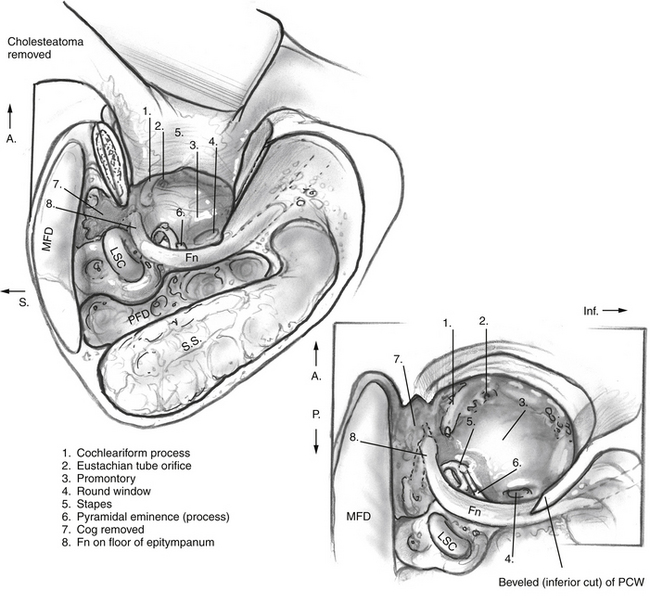

The cholesteatoma is carefully dissected from the tympanic cavity, epitympanum, antrum, and mastoid (see Fig. 14-3). The cog is drilled, and the anterior epitympanic space is cleared of any residual disease, as is the sinus tympani. The zygomatic root air cells are drilled away similar to a canal wall down procedure. The wall down exposure provides undivided access to the mastoid, tympanic cavity, and antrum allowing for optimal exposure to the cholesteatoma to aid with complete removal (Fig. 14-4).

Reconstruction

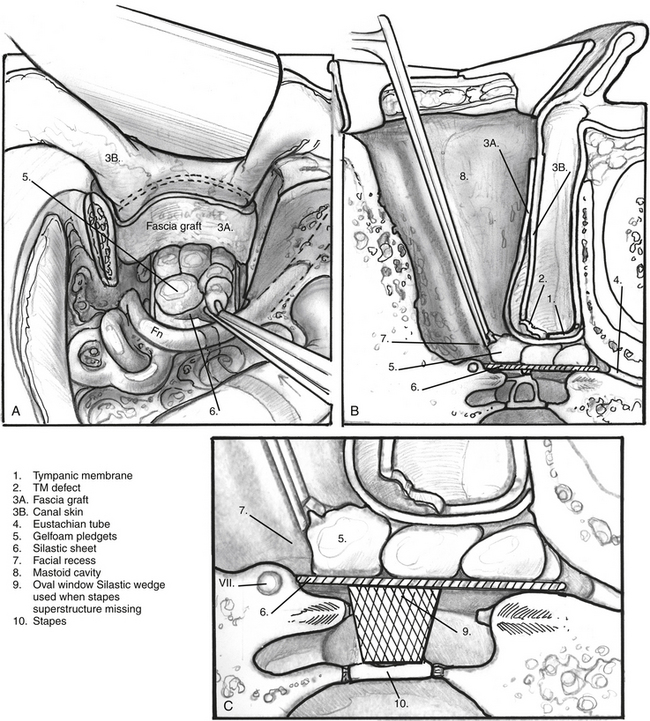

Reconstruction begins with the placement of a teardrop-shaped piece of reinforced silicone elastomer (Silastic) (0.04 mm thick) into the middle ear with the neck extending into the eustachian tube. The Silastic graft rests on top of the stapes superstructure (if present) and extends into the eustachian tube, but does not extend posteriorly into the facial recess (Fig. 14-5A and B). In patients without an intact stapes superstructure, an additional wedge-shaped piece of Silastic is placed onto the footplate, resting underneath the larger teardrop-shaped Silastic graft (Fig. 14-5C); this holds a space for reconstruction during a second look procedure. A temporalis fascia graft is then harvested. This graft must be large enough to extend beyond the margins of the posterior canal wall cuts. The temporalis fascia is placed medial to the tympanic membrane remnant, extending laterally to the bony-cartilaginous junction. Absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) disks are placed between the Silastic graft and the underlay fascia graft to hold it in place (see Fig. 14-5A and B).

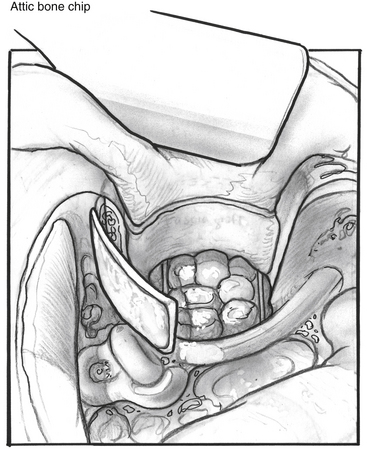

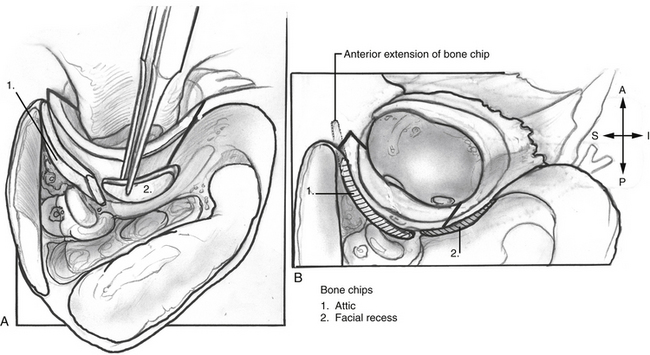

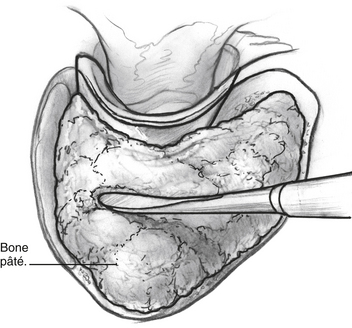

A large calvarial bone slice is trimmed to extend from the zygomatic root to the margin of the posterior canal wall and placed in a near-axial orientation into the epitympanum to prevent future retraction of the grafted drum. The attic bone chip extends from the anterior epitympanum posteriorly to the posterior aspect of the lateral semicircular canal, and is wide enough to span from the tympanic facial nerve in a lateral direction to beyond the scutum (Fig. 14-6). The bony posterior canal wall is replaced, and an additional calvarial bone graft is placed in a near-coronal orientation into the facial recess (Fig. 14-7). The attic, antrum, and mastoid complex is filled with bone pâté, and dry gauze is used to compress the pâté in place and wick off excess bacitracin solution from the pâté (Fig. 14-8).

Attention is turned to the ear canal where a thin Cottle speculum is used along with the operating microscope to displace the posterior canal skin onto the bony posterior canal wall and visualize the tympanic membrane remnant. The underlay fascial graft is inspected through the perforation in the tympanic membrane remnant to verify that there is complete coverage of the perforation, and to ensure that no slippage of the graft has occurred during the reconstruction of the canal wall and obliteration of the mastoid cavity. Gelfoam is placed lateral to the grafted tympanic membrane, and the EAC is packed with ¼ inch iodoform strip gauze that has been soaked in bacitracin ointment (Fig. 14-9). The Palva flap is closed with absorbable sutures. A ¼ inch Penrose drain is placed between the Palva flap and the postauricular flap and trimmed to size before closure of the postauricular tissues. The drapes are removed, and a sterile mastoid dressing is applied.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS

Complications of canal wall up procedures, such as tympanic membrane perforation and extrusion of ossiculoplasty prostheses, can occur with the canal wall reconstruction technique, but their incidence can be minimized by meticulous attention to the placement of the fascial underlay graft (see Figs. 14-5B and 14-9), and the coverage of the titanium ossiculoplasty prosthesis with a cartilage graft.

A greater concern with the canal wall reconstruction procedure is the possibility of wound infection, which theoretically could progress to involve the mastoid bone pâté and posterior canal wall. Careful attention to numerous details in the canal wall reconstruction technique can effectively reduce the incidence of infection.16 First, perioperative antibiotics, with double coverage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are an important measure in preventing wound infections. Typically, patients are given piperacillin-tazobactam and levofloxacin intravenously before surgery and for 48 hours postoperatively. Patients are discharged on a 2-week course of oral levofloxacin. Pediatric patients are given piperacillin-tazobactam perioperatively and discharged on amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 2 weeks. Penicillin-allergic patients are given clindamycin and piperacillin-tazobactam perioperatively and complete a 2-week course of clindamycin postoperatively. Second, bone pâté is collected from nondiseased cortical bone and is soaked in bacitracin solution before placement in the mastoid. Pâté collection is stopped if air cells become exposed during the drilling process. Third, placement of a Penrose drain between the postauricular skin flap and the Palva flap for 48 hours postoperatively helps to prevent the formation of a hematoma, which may subsequently become infected.

Re-retraction of the tympanic membrane can occur with any intact canal wall procedure (canal wall up or canal wall reconstruction), and can lead to recidivistic cholesteatoma. In the canal wall reconstruction procedure, the placement of large bone chips in the attic and facial recess prevents potential re-retraction. It is important that a large bone chip be carefully placed in a near-axial orientation into the attic, extending from the anteriormost part of the epitympanum to the posterior aspect of the lateral semicircular canal (see Fig. 14-6) and from the tympanic facial nerve well lateral to the medialmost extent of the posterior bony canal wall, which may have been eroded by cholesteatoma (see Fig. 14-7). The bone chip in the facial recess is placed in a near-coronal orientation and completely blocks this space, effectively separating the mastoid from the tympanic cavity (see Fig. 14-7).

1. Ucar C. Canal wall reconstruction and mastoid obliteration with composite multi-fractured osteoperiosteal flap. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:1082-1086.

2. Sudhoff H., Brors D., Al-Lawati A., et al. Posterior canal wall reconstruction with a composite cartilage titanium mesh graft in canal wall down tympanoplasty and revision surgery for radical cavities. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:832-836.

3. Reck R., Helms J. The bioactive glass ceramic Ceravital in ear surgery: Five years’ experience. Am J Otol. 1985;6:280-283.

4. Bagot d’Arc M., Daculsi G., Emam N. Biphasic ceramics and fibrin sealant for bone reconstruction in ear surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:711-720.

5. Leatherman B.D., Dornhoffer J.L. The use of demineralized bone matrix for mastoid cavity obliteration. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:22-25.

6. Estrem S.A., Highfill G. Hydroxyapatite canal wall reconstruction/mastoid obliteration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:345-349.

7. Shea J.J.Jr., Malenbaum B.T., Moretz W.H.Jr. Reconstruction of the posterior canal wall with Proplast. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:329-333.

8. Roberson J.B.Jr., Mason T.P., Stidham K.R. Mastoid obliteration: Autogenous cranial bone pate reconstruction. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:132-140.

9. Zini C., Quaranta N., Piazza F. Posterior canal wall reconstruction with titanium micro-mesh and bone pate. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:753-756.

10. Moffat D.A., Gray R.F., Irving R.M. Mastoid obliteration using bone pate. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19:149-157.

11. Bacciu S., Pasanisi E., Vega Feijoo S., et al. [Total reconstruction of the posterior wall of the external ear canal with allogenic rib cartilage: Technique and results]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1997;48:599-604.

12. Geyer G., Dazert S., Helms J. Performance of ionomeric cement (Ionocem) in the reconstruction of the posterior meatal wall after curative middle-ear surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1130-1136.

13. Lenis A. Hydroxylapatite canal wall reconstruction in patients with otologic dilemmas. Am J Otol. 1990;11:411-414.

14. Grote J.J., van Blitterswijk C.A. Reconstruction of the posterior auditory canal wall with a hydroxyapatite prosthesis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1986;123:6-9.

15. Mercke U. The cholesteatomatous ear one year after surgery with obliteration technique. Am J Otol. 1987;8:534-536.

16. Gantz B.J., Wilkinson E.P., Hansen M.R. Canal wall reconstruction tympanomastoidectomy with mastoid obliteration. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1734-1740.

17. Palva T. Surgical treatment of chronic middle ear disease, II: Canal wall up and canal wall down procedures. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987;104:487-494.

18. Abramson M. Open or closed tympanomastoidectomy for cholesteatoma in children. Am J Otol. 1985;6:167-169.

19. Shohet J.A., de Jong A.L. The management of pediatric cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:841-851.

20. Rosenfeld R.M., Moura R.L., Bluestone C.D. Predictors of residual-recurrent cholesteatoma in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:384-391.

21. Ars B., Wuyts F., Van de Heyning P., et al. Histomorphometric study of the normal middle ear mucosa: Preliminary results supporting the gas-exchange function in the postero-superior part of the middle ear cleft. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:704-707.