Chapter 24 Can We Prevent Children’s Fractures?

Injury is currently one of the leading causes of burden of disease, accounting for 9% of worldwide morbidity and mortality combined in 1998. Injury is expected to account for a much greater share—14% of global morbidity and mortality by 2020.1,2 The expected increase is attributable both to increased motorization leading to a greater burden of road traffic crashes, and to the demographic and epidemiologic transition whereby diseases of poverty (malnutrition, infections) become replaced by those of affluence (trauma, diabetes, heart disease, cancer) as global wealth increases and population growth rates slow.3

BONE HEALTH AND FRACTURES AMONG HEALTHY CHILDREN

Increasing longevity puts more of the population at risk for osteoporotic fractures in old age. Ensuring attainment of the greatest possible peak bone mass in childhood and adolescence is an obvious but difficult to implement step at a societal level. Attainment and maintenance of bone mass relies on adequate dietary calcium, availability of vitamin D, weightbearing exercise, and hormonal milieu. Peak bone mass is attained by early adulthood and declines thereafter; therefore improving bone health for a lifetime requires interventions in childhood and adolescence.4 Whether these same interventions will reduce childhood or adolescent fractures is unclear. A transient osteoporosis of adolescence coinciding with peak height growth velocity has been hypothesized, and it may increase fracture incidence at this time.

Randomized, controlled trial (level I) evidence demonstrates that oral calcium supplementation increases the bone mineral density (BMD) of female children during the pubertal growth spurt; however, at 7 years of follow-up, there was no difference in total body BMD and distal radius BMD.5 A randomized, controlled trial combining exercise intervention and calcium supplementation in 16- and 18-year-old girls found a significant increase in BMD (at 1 year) with calcium supplementation, but no additional effect from a weightbearing exercise program prescribed to individuals.6 A prospective, nonrandomized study from Sweden (level II evidence) used a school-based exercise program and showed that classes of girls given daily physical exercises had improved BMD and bone width compared with classes doing physical exercise once per week.7

An increased risk for forearm fractures from reduced BMD has been established prospectively for girls using a cohort design (level II evidence)8 and retrospectively for boys using a case–control design (level III evidence).9 In both of these studies, an increased body mass index was also found to be an independent predictor of increased fracture risk.

BONE HEALTH AND FRACTURES AMONG CHILDREN WITH COMORBIDITIES

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a group of related conditions in which defects in collagen production lead to bony fragility and fractures. Bone turnover is high, particularly during the growing years. Bisphosphonates decrease osteoclastic resorption of bone, leading to increased bone mass and bone strength. Two randomized, controlled trials (level I evidence) support treating patients with osteogenesis imperfecta with oral bisphosphonates. One trial randomized 34 children to either oral olpadronate (10 mg/m2 daily) or placebo, in addition to calcium and vitamin D for all patients. A 2-year parallel arm design was used. Olpadronate-treated patients had a 31% reduction in long-bone fracture risk. Increases in BMD and bone mineral content were statistically significantly greater among olpadronate-treated patients. No difference was found in overall quality of life.10 A second trial randomized 17 children to oral alendronate or placebo in a blinded crossover study and showed increases in BMD, increases in quality of life in the domains of pain, analgesic use, and well-being, as well as decreases in the number of fractures during the time of alendronate treatment.11

Earlier studies regarding bisphosphonates for Osteogenesis imperfecta were case series (level IV evidence) that documented increased bone mineral densities, decreased serum markers of bone turnover, and decreased numbers of fractures after treatment with intravenous pamidronate.12–15

Cerebral Palsy/Neuromuscular Conditions

Patients with cerebral palsy are at risk for osteoporosis and fractures. Decreased weightbearing stimulus and altered vitamin D metabolism, related to lack of sun exposure and to anticonvulsant medication, have been postulated as mechanisms. A randomized, controlled trial (level I evidence) of increasing the time of the standing program for nonambulant children with cerebral palsy demonstrated an increase in vertebral but not tibial BMD with increased standing. Only 26 patients were randomized, no effect on fractures was noted (perhaps because of small numbers), and the clinical significance of the vertebral BMD differences was unclear.16 A causative study using a case–control design (level III evidence) compared 20 patients with fractures with 20 age-matched control subjects from a population of children and young adults with spastic quadriplegia in residential care.17 Anticonvulsant therapy was strongly associated with both the occurrence of fractures and abnormally high serum alkaline phosphatase, indicating high bone turnover. Radiographic signs of rickets were present in many of the fracture patients. After administration of vitamin D and calcium, the radiographic findings and the high serum alkaline phosphatase normalized (level IV evidence, case series), although there was not adequate follow-up to determine subsequent fracture risk. Two level IV studies support the use of oral18 or intravenous19 bisphosphonate in nonambulant patients with cerebral palsy by documenting increased BMD and decreased fracture incidence during treatment.

Steroid Treatment

Steroid-induced osteoporosis is a well-described consequence of chronic steroid use, which is indicated in many pediatric medical conditions. A retrospective cohort study (level III evidence) found that inhaled steroid use (for asthma) of 800 g/day or more significantly decreased lumbar spine BMD. The effect was more pronounced if oral steroids were also used. Only 76 patients were analyzed, and fracture outcomes were not reported.20

Among patients with renal transplant taking chronic oral steroid, one randomized trial (level I evidence) has shown significant increase in BMD with oral vitamin D treatment or with nasal calcitonin treatment, but no significant effect of alendronate alone.21 Using alendronate without supplementing calcium and vitamin D is an unusual choice, and the negative result regarding alendronate from this trial is therefore suspect.

Another study grouped children receiving chronic oral steroids who had suffered fractures and compared them with those receiving steroids who did not have fractures. Those who had had fractures were treated with intravenous pamidronate plus steroid, and those who had not continued on steroid alone. All children in both groups were prescribed calcium and vitamin D. After pamidronate treatment, there was significant improvement in lumbar spine BMD, compared with significant loss among the steroid alone group. This comparative cohort study can be considered level of evidence III because only one of the arms was gathered prospectively.22

PREVENTION OF REFRACTURES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Forearm Fractures

A case series (level IV evidence) published in 1996 described 28 forearm refractures of which 25 had known causes. Twenty-one (84%) of them were related to incomplete consolidation of the tensile side of a diaphyseal greenstick fracture.23 The article did not include data on patients without refractures, so no firm conclusions can be drawn about preventing this event.

A subsequent article published in 1999 used a retrospective case–control design to analyze 768 primary forearm fractures in children of which 38 (4.9%) had refractures.24 All primary fractures included were treated under general anesthesia by closed or open means. The strongest predictor of refracture risk was the location of the fracture, with 14.7% of diaphyseal fractures suffering a refracture, compared with 2.7% of metaphyseal radius fractures, 1.5% of metaphyseal both bones fractures, and 0% of physeal fractures (P, 0.001). The second most important predictor was the duration of cast immobilization, with a refracture rate of 6% among fractures immobilized 6 weeks or less, 4% among fractures immobilized 4 to 6 weeks, and 1% among those immobilized over 6 weeks. The median time to fracture after cast removal was 8 weeks, with most refractures happening within 16 weeks of cast removal. Based on this level III evidence, one can recommend 6 weeks of cast immobilization for diaphyseal fractures and activity restriction for 16 weeks after cast removal.24

Femur Fractures

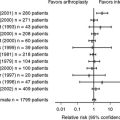

External fixation of femur fractures may present a greater risk for refracture than other treatment methods because the stiff frame may delay consolidation and then is removed abruptly. The true risk for refracture is not known and may be no greater with external fixation than with other means. The only randomized trial comparing external fixators to casts found a 4% refracture rate with external fixators and 0% with casts, a difference that was not statistically significant given the numbers involved (level of evidence I).25

A retrospective comparative study of 66 femoral fractures treated with external fixation found 8 refractures (12%) and found that the risk for refracture was 33% if fewer than 3 cortices had bridging callus at the time of fixator removal compared with 4% if 3 or 4 cortices demonstrated bridging callus.26 According to this level III evidence, the recommendation would be to leave external fixators in place until three or four cortices show bridging callus, to minimize the risk for refracture with this technique. Table 24-1 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

| Weightbearing exercise and dietary calcium supplementation improve bone mass in female adolescents. | A | 5, 6 |

| Forearm fracture risk is greater during childhood among girls and boys with lower bone mineral density. | B | 8, 9 |

| Oral bisphosphonates reduce fracture risk and increase quality of life in patients with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. | A | 10, 11 |

| Intravenous bisphosphonates increase bone mineral density and decrease fractures in patients with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. | C | 12–15 |

| Inhaled steroids of more than 800 μg/day decrease bone mineral density in growing children. | B | 20 |

| Bisphosphonate plus calcium and vitamin D substantially improves bone mineral density among patients taking chronic oral steroids. | B | 22 |

| Forearm refractures in children are strongly associated with cast removal before 6 weeks. | B | 24 |

| Femoral refractures after external fixator removal are uncommon if three or four cortices have bridging callus at the time of fixator removal and more common if two or fewer cortices have bridging callus. | A, B | 25, 26 |

1 Murray C, Lopez A. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498-1504.

2 Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:523-526.

3 Beveridge M, Howard A. The burden of orthopaedic disease in developing countries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1819-1822.

4 . Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH Consensus Statement.; 17; 2000; 1-45. consensus.nih.gov.

5 Matkovic V, Goel PK, Badenhop-Stevens NE, et al. Calcium supplementation and bone mineral density in females from childhood to young adulthood: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:175-188.

6 Stear SJ, Prentice A, Jones SC, Cole TJ. Effect of a calcium and exercise intervention on the bone mineral status of 16–18-y-old adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:985-992.

7 Valdimarsson O, Linden C, Johnell O, et al. Daily physical education in the school curriculum in prepubertal girls during 1 year is followed by an increase in bone mineral accrual and bone width—data from the prospective controlled Malmo pediatric osteoporosis prevention study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78:65-71.

8 Goulding A, Jones IE, Taylor RW, et al. More broken bones: A 4-year double cohort study of young girls with and without distal forearm fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2011-2018.

9 Goulding A, Jones IE, Taylor RW, et al. Bone mineral density and body composition in boys with distal forearm fractures: A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry study. J Pediatr. 2001;139:509-515.

10 Sakkers R, Kok D, Engelbert R, et al. Skeletal effects and functional outcome with olpadronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: A 2-year randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2004;363:1427-1431.

11 Seikaly MG, Kopanati S, Salhab N, et al. Impact of alendronate on quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:786-791.

12 Grissom LE, Kecskemethy HH, Bachrach SJ, et al. Bone densitometry in pediatric patients treated with pamidronate. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:511-517.

13 DiMeglio LA, Ford L, McClintock C, Peacock M. Intravenous pamidronate treatment of children under 36 months of age with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2004;35:1038-1045.

14 Lee YS, Low SL, Lim LA, Loke KY. Cyclic pamidronate infusion improves bone mineralisation and reduces fracture incidence in osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:641-644.

15 Glorieux FH, Bishop NJ, Plotkin H, et al. Cyclic administration of pamidronate in children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:947.

16 Caulton JM, Ward KA, Alsop CW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of standing programme on bone mineral density in non-ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:131-135.

17 Bischof F, Basu D, Pettifor JM. Pathological long-bone fractures in residents with cerebral palsy in a long-term care facility in South Africa. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:119-122.

18 Sholas MG, Tann B, Gaebler-Spira D. Oral bisphosphonates to treat disuse osteopenia in children with disabilities: A case series. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:326-331.

19 Plotkin H, Coughlin S, Kreikemeier R, et al. Low doses of pamidronate to treat osteopenia in children with severe cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:709-712.

20 Harris M, Hauser S, Nguyen TV, et al. Bone mineral density in prepubertal asthmatics receiving corticosteroid treatment. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:67-71.

21 El-Husseini AA, El-Agroudy AE, El-Sayed MF, et al. Treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis in renal transplant children and adolescents. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:357-361.

22 Acott PD, Wong JA, Lang BA, Crocker JFS. Pamidronate treatment of pediatric fracture patients on chronic steroid therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:368-373.

23 Schwarz N, Pienaar S, Schwarz AF, et al. Refracture of the forearm in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:740-744.

24 Bould M, Bannister GC. Refractures of the radius and ulna in children. Injury. 1999;30:583-586.

25 Wright JG, Wang EE, Owen JL, et al. Treatments for paediatric femoral fractures: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1153-1158.

26 Skaggs DL, Leet AI, Money MD, et al. Secondary fractures associated with external fixation in pediatric femur fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:582-586.