CHAPTER 30 Calcific Tendinitis

Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder is a self-limiting calcification of the rotator cuff. It can be categorized as an enthesopathy of the shoulder, and is characterized by inflammation around calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposits, usually located in the supraspinatus tendon, near its insertion site. These radiologically evident calcific deposits have been reported in 2.7% to 20% of asymptomatic adult patients1,2 and in 6.8% of adult patients with shoulder pain.2 The discomfort associated with the calcification is believed to be caused by inflammation around calcium deposits located in or around the rotator cuff tendons. The process consists of a multifocal cell-mediated calcification of a living tendon that is usually followed by spontaneous phagocytic resorption.3 After resorption or surgical removal of the deposit(s), the tendon reconstitutes itself.4 When this condition becomes painful, it usually has an abrupt onset and can severely limit physical activity, even though its formation is not necessarily activity-dependent. It is believed that the disease only becomes acutely painful when the calcium is undergoing resorption.

The disorder is most common among people between 30 and 60 years old. Women are slightly more likely to be affected than men, and workers in sedentary jobs appear to be at higher risk than those in manual labor.5 Bilateral involvement is not uncommon. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination, with specific attention to radiographic evidence of calcification. Patients usually exhibit specific tenderness over the greater tuberosity and symptoms similar to those of impingement syndrome.

HISTORICAL REVIEW

In 1907, Painter was the first to describe the radiographic findings in patients with calcific tendinitis of the shoulder.6 Codman discussed the problem in the 1930s and described the pathology as located primarily within the supraspinatus tendon, adjacent to the insertion on the greater tuberosity, but could also be found within the subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor.7 In the 1940s, Bosworth reviewed radiographs and examined 6061 employees of an insurance company and found an incidence of 2.7% of calcific deposits in the shoulder. Of these, 51.5% of the deposits were in the supraspinatus tendon.8

PATHOGENESIS

Considerable controversy remains regarding the cause of this condition. Codman proposed that degenerative changes were necessary before the tendon would calcify.7 Conversely, Uhthoff and others do not believe that degeneration plays a role in calcium deposition, but that calcification is actively mediated by cells in a specific local environment; the age distribution and self-limiting course of the disease mitigates against degeneration as the cause.4

The disorder has four stages. The first, the precalcific stage, involves asymptomatic fibrocartilaginous transformation within the tendon. In the second stage, the formative stage, calcification develops within the cuff. This process may produce no symptoms or may be associated with variable degrees of pain at rest or on movement, especially abduction. The third stage, the resorptive stage, is the most incapacitating for patients, because extravasation of the calcium crystals into the subacromial bursa may cause constant severe pain and restriction of movement that typically lasts for 1 to 2 weeks. During this stage, systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise may be present. Some patients may even have elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates and neutrophilia.9 The differential diagnosis in such patients includes joint sepsis and gout. The final stage, the postcalcific stage, involves healing and repair of the rotator cuff. This phase may last several months and may be associated with some pain and restriction of function.

Pain is thought to be an inflammation-induced response to the local chemical pathologic disorder and to direct mechanical irritation. Neer has described four possible causes for pain associated with calcium deposits.10 First is pain caused by chemical irritation induced by the calcium crystals. Most commonly, this presents as a bursitis, but may occasionally present as an inflammatory synovitis that can be clinically difficult to distinguish from septic arthritis. The second source of pain is pressure within the tissue as it swells, described by Codman as a “chemical furuncle.”7 The third is an impingement-type pain caused by bursal thickening and irritation. The fourth cause is the chronic stiffening of the joint (frozen shoulder), which may occur as a result of holding the affected arm continually at the side to avoid irritating the calcium deposit(s).

The most common site for occurrence is within the supraspinatus tendon and at a location 1.5 to 2.0 cm medial to the insertion on the greater tuberosity.4,10 Other affected sites include the infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis tendon, in descending order of frequency. It almost always has an onset in those who are older than 30 years, and it affects up to 20% of the population. Up to 10% have bilateral involvement.11 Most patients are asymptomatic. Patients with diabetes are more likely to develop asymptomatic deposits; more than 30% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes have tendon calcification.11 According to an arthrographic study,12 a rotator cuff tear may coexist in approximately 25% of patients presenting with calcific shoulder tendinitis. Surprisingly, small rather than large calcification deposits are more likely to be associated with cuff pathology.12

PRESENTATION

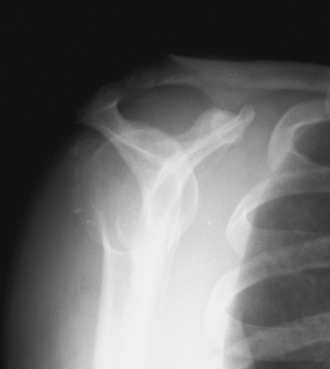

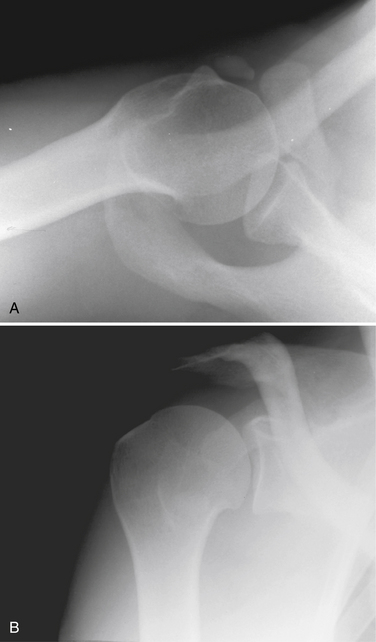

The diagnosis of calcific tendinitis is confirmed by radiographic evidence of calcification that is restricted to the tendon and usually does not affect he bone. Plain radiographs are valuable for two reasons. The first is for diagnosis and localization of the calcific deposit. The second is to follow changes during treatment. A routine shoulder series (anteroposterior [AP] views in internal rotation [IR] and external rotation [ER], outlet, and axillary) is initially obtained. These can be supplemented with additional views if further localization of calcium is needed. Calcium deposits located in the supraspinatus tendon can be seen on a true AP view of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 30-1). Internal and external rotation AP views are used to localize deposits further in the infraspinatus and supraspinatus, respectively. In addition, a supraspinatus outlet view helps localize supraspinatus deposits to the anterior subacromial region and deposits in the infraspinatus to the posterior region (Fig. 30-2). Acromial morphology and the presence of any subacromial osteophytes are also detected on an outlet view. The axillary view is useful for identifying deposits within the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 30-3). The Zanca view for the acromioclavicular joint (10-degree cephalic tilt) is part of a routine shoulder series and the calcific deposit is often seen clearly. DePalma and Kruper11 have described calcifications on radiographs as dense and well defined in the formative stage, but cloudlike or irregular in the resorptive phase. Calcific tendinitis must be distinguished from dystrophic calcification associated with rotator cuff disease that occurs closer to the tendon insertion. The latter carries a worse prognosis and is not associated with the eventual resorption of calcium and resolution of symptoms. Stippled calcification or calcification that extends into bone is associated with glenohumeral arthropathy; such degenerative radiologic signs are rare in individuals with calcific tendinopathy.4

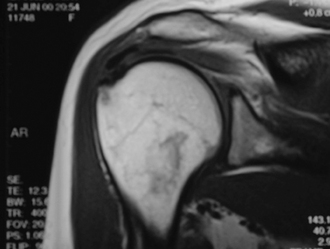

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation is not indicated routinely. The calcifications appear as areas of decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted images, whereas T2-weighted images may show an area of increased signal intensity surrounding the lesion similar to that of edema (Fig. 30-4).

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Although the disease has historically been considered to be self-limiting, spontaneous disappearance of periarticular calcifications was reported in only 9.3% of patients after 3 years and 27% after 10 years.13 Chronic pain is possible along with occasional acute flare-ups, which can cause significant morbidity. The treatment of calcific tendinitis is typically conservative, with the reported success rate between 30% and 85%.14

Nonoperative Treatment

Numerous nonsurgical approaches have been used to treat painful calcific tendinitis. The goal of therapy is to control pain and maintain function. During the acute and/or painful stage of the disorder, patients may need to rest the affected arm in a sling. During all phases of the disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a mainstay. Subacromial steroid injections may be beneficial if the patient shows impingement signs.15 Some authors recommend subacromial injections specifically during the formative (chronic) phase to relieve impingement pain.4 To the contrary, Lippmann has warned that corticosteroids may inhibit the cellular activity that produces disruption of the calcium deposit.16

Once pain is controlled, function may be maintained through exercises for range of motion and rotator cuff strengthening. There is mixed evidence that therapeutic ultrasound is more effective than placebo ultrasound for treating patients with calcific tendinitis.17 However, in a well-designed, randomized, double-blind comparison study of ultrasound and sham treatment in patients with calcific tendinitis, the patients who received ultrasound treatment had greater decreases in pain and greater improvements in quality of life.18 This short-term clinical improvement also correlated well with a decrease in calcium deposit size on radiographs.

Needling a calcium deposit with or without lavage during the resorptive phase is a treatment that has met with variable success.11,19 It is believed to work by decompressing the intratendinous pressure of the calcium deposit. More recent studies have shown that a modified ultrasound-guided needle technique is an effective therapy with a significant clinical improvement and perhaps greater precision in localizing the deposits.20 Using this ultrasound-guided needle technique, Farin and colleagues21 found favorable outcomes in more than 70% of patients. In our practice, if a patient presents with acute pain and difficulty with motion, and demonstrates a calcific deposit on radiographs, an immediate attempt to needle the deposit will be made. A combination of anesthetic and steroid will also be injected into the suspected area of the deposit and into the subacromial space. This will often provide immediate and significant relief. On occasion, a white-colored aspirate is retrieved, indicating a direct hit of the deposit. A therapy program is then initiated.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been postulated to be an effective option for treating calcific tendinitis of the shoulder, and obviates the need for surgery. Shock waves with pressure impulses may be capable of producing fragmentation of calcific deposits with a reduction of pain. High-energy shock wave therapy should be considered before surgery in patients with chronic calcific tendinitis who have undergone a minimum of 6 months of unsuccessful conservative treatment and/or clinical signs of subacromial impingement.22 Loew et and associates23 have suggested that a deposit with a diameter of at least 10 mm should be evident before ESWT is contemplated. Numerous case series, nonrandomized controlled trials, and more recent randomized trials have demonstrated clinical improvement and dissolution of the calcifications with both high- and low-energy ESWT.23–28

Surgical Therapy

If nonsurgical efforts to relieve pain and restore function are unsuccessful, and other diagnoses have been eliminated, a surgical approach to the problem is a viable alternative. This is usually necessary in the chronic formative phase. Traditionally, this was done as an open procedure. Bosworth,8 in 1941, described open surgery as being the quickest and most dependable way to eliminate the pain and avoid an impending frozen shoulder. More recently, arthroscopic techniques have been developed to excise the calcific deposit. Advantages may include a shorter rehabilitation time, better functional result, and better cosmetic appearance. Several studies have attempted to establish the efficacy of arthroscopic treatment for refractory cases of calcific tendinitis.29–31

Ark and coworkers29 treated 23 patients with an arthroscopic excision of their calcific deposit. Concomitant subacromial decompression was performed in 3 patients who exhibited a “bony acromial overhang.” Of their patients, 91% had a good or satisfactory result. In this series, complete removal of calcium was not achieved in 14 patients, but significant pain relief was obtained in 12 of these patients. The authors concluded that complete excision of the calcium deposit is not necessary, nor is an acromioplasty, unless significant signs and symptoms of impingement are present.

Jerosch and colleagues30 evaluated 48 of 57 patients treated arthroscopically for calcific tendinitis. Constant scores improved from 38 before surgery to 86 after surgery. In their series, an acromioplasty was not associated with a significant improvement in the results. High success rates for arthroscopic excision of the calcific deposit were reported by Molé and associates31 in a multicenter study conducted by the French Society of Arthroscopy. Of their patients, 88% had complete disappearance of the calcific deposit and 82% were satisfied with the result. In this series, acromioplasty did not influence outcome. Seil and coworkers32 confirmed these previously reported successful results of arthroscopic treatment of calcific tendinitis. In their case series of 58 consecutive patients who underwent arthroscopic removal of calcific deposits in the supraspinatus tendon, 78% of patients returned to work within 6 weeks, irrespective of their profession. At the final follow-up (24 months), 92% of patients were very satisfied with the outcome.

Surgical Principles

To ensure optimal results, complete removal of the calcium deposit should be attempted. Therefore, accurate localization of the deposit prior to surgery is essential. As noted, this can be achieved with the use of radiographs in different planes to highlight different areas of the shoulder. Other studies, such as MRI and/or ultrasound, may provide additional three-dimensional information about calcium location. A recent study by Kayser and colleagues33 has demonstrated that preoperative ultrasound-guided marking of calcific deposits significantly improves the clinical results of arthroscopic surgery. When a clear understanding of the location of the deposit is known, the surgical procedure may be undertaken. The preoperative radiographs and MRI should be available in the operating room for further review.

Surgical Technique

The procedure may be performed under interscalene regional block or general endotracheal tube anesthesia. Positioning may be beach chair or lateral decubitus. We perform the procedure under general anesthesia in the lateral decubitus position with 5 to 7 pounds of suspension. The posterior soft spot of the shoulder is palpated. This is approximately 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterior lateral corner of the acromion. The exact position is then localized with an 18-gauge spinal needle directed anteriorly into the joint toward the coracoid tip. Fifty mL of saline are injected into the joint, and brisk backflow of fluid through the spinal needle confirms placement within the joint and suggests an intact cuff. Fluid distention allows for an easier entry into the joint with less chance of damaging articular surfaces. Because most of the work is to be carried out in the subacromial space, this portal can be placed slightly superiorly to facilitate placement of the arthroscope into this space. This allows easier maneuvering superior to the humeral head.

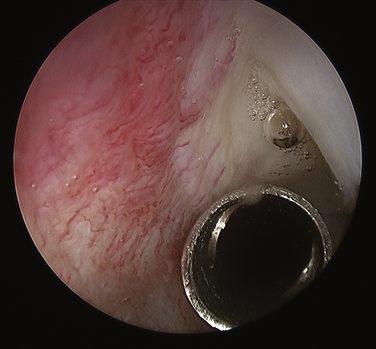

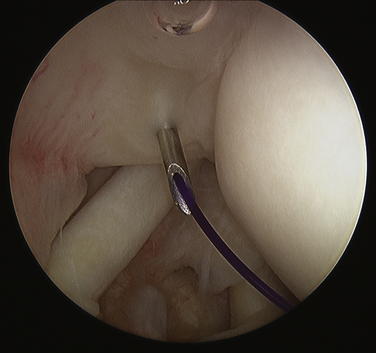

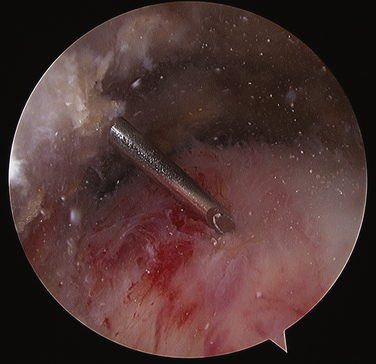

Routine glenohumeral arthroscopy is carried out. On entering the glenohumeral joint, there will usually be moderate inflammation of the synovium. Careful inspection of the undersurface of the rotator cuff, particularly in the area of the suspected calcium deposit, is performed, looking for a suspicious bulge, an area of hyperemia, or any signs of capsule or tendon damage (Fig. 30-5). To delineate the location of the calcium, we generally will bring an 18-gauge spinal needle approximately 1 cm lateral to the acromion, in line with the posterior aspect of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. The needle transgresses the supraspinatus just posterior to the biceps tendon, which is a typical location for calcium deposits. Often, when the needle enters the joint, one can see some calcium crystals at the end of the needle. When the suspicious area is identified, a no. 1 colored monofilament suture is introduced through the needle as a marking stitch (Fig. 30-6). This PDS (polydiaxonone) suture can be identified in the subacromial space and will assist in locating the deposit. The suture is pushed well into the joint so that it remains across the tendon when the needle is removed. Careful planning is used to keep the lateral entry of the suture away from the anterior lateral portal that will be created to perform the subacromial portion of the procedure. We also take into account the confines of the bursa when placing the marking suture, because the posterior aspect of the bursa is usually located at about the midportion of the acromion. If the suture is placed outside the bursa, usually posteriorly, it will be more difficult to identify. If the calcific deposit is located more posteriorly, however, this may be unavoidable.

A subacromial decompression is usually performed, because many of these patients also have impingement caused by thickening of the cuff. If preoperative imaging demonstrates a subacromial spur, it is removed to create a flat acromion. If, on the other hand, no spur is present, a minimal acromioplasty is performed to create slightly more space for the supraspinatus, which may thicken slightly after the procedure from scarring. If a patient demonstrated preoperative acromioclavicular tenderness and arthritic changes on x-ray, a distal clavicle resection can be performed at this time.

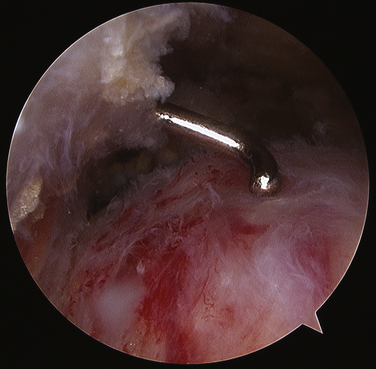

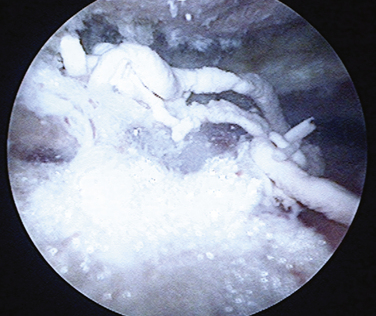

At this point, attention is turned toward the rotator cuff. There is usually a thin veil of bursa remaining overlying the rotator cuff. It can be removed with a full-radius resector with little or no bleeding. The blue color of the Prolene marking suture is identified (Fig. 30-7). Sometimes this requires the abduction of the arm back up to the 70-degree position if the suture is placed too far laterally. With internal or external rotation of the shoulder and abduction as needed, the involved area of the tendon can be brought into clear view, within easy access of the anterior lateral portal. If the calcium deposit is not easily identified, an 18-gauge spinal needle is used to penetrate the rotator cuff in the region of the marking stitch until the calcium deposits become apparent. If a marking suture has not been placed, the bursal surface of the tendon is inspected for a suspicious bulge, an area of hyperemia, or any signs of damage. This region is then needled to identify the calcium deposit (Fig. 30-8).

FIGURE 30-8 Needling the rotator cuff in the area of suspected calcification, with resultant calcium snow storm (same view as in Fig. 30-7).

As the deposit is needled, calcium is liberated and will often be seen as a snow storm (see Fig. 30-8). With the precise location of the calcium identified, an attempt is made to remove the entire deposit. If the calcium is fairly acute and liquid, it will start to ooze out through the spinal needle hole. Once the calcium is located, the spinal needle is used to create a 5- to 7-mm opening in the cuff, in line with its fibers. The probe is used to put pressure on the surrounding cuff and milk the calcium out of the deposit (Fig. 30-9). If there is any question as to whether any calcium remains, or the location cannot be identified, an intraoperative radiograph can be taken. Fluoroscopy can also be used (see Fig. 30-5). In the event that insufficient calcium is excised, or if the deposit cannot be found, a miniopen approach can be used and the cuff palpated manually to find the calcium deposits.

FIGURE 30-9 Toothpaste-like appearance of the calcium deposit as it is milked out of the rotator cuff tendon.

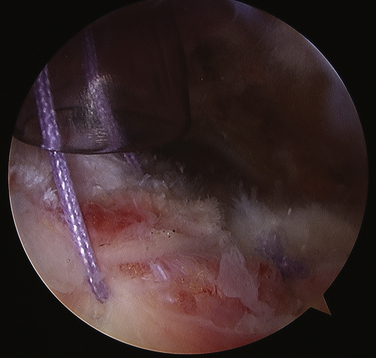

The resulting damage to the tendon must now be assessed. If the tendon involvement is superficial or if there is a small longitudinal split, no further treatment is necessary. If the split appears more involved or if the tendon is damaged to the point of concern, sutures can be placed arthroscopically to close the defect (Fig. 30-10). We prefer using long-acting, braided, absorbable sutures. If the tendon insertion to the greater tuberosity is found to be disrupted, it must be repaired using a suture anchor technique, either arthroscopically or with a miniopen approach.

FIGURE 30-10 Closure of the defect in the supraspinatus tendon after removal of the calcium deposit.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

1. Welfing J, Kahn MF, Desroy M, et al. Les calcification de l’epaule. La maladie des calcifications tendineuses multiples. Rev Rhum. 1965;32:325-334.

2. Ruttimann G Uber die Haufigkeit roentgenologischer Veranderungen bei Patienten mit typischer Periarthritis humeroscapularis und Schultergesunden Dissertation. Zurich, Switzerland: University of Zurich; 1959.

3. Uhthoff HK, Sarkar K. Calcifying tendonitis. In: Rockwood CAJr, Matsen FAIII, editors. The Shoulder. Vol 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:774-790.

4. Uhthoff HK, Loehr JW Calcific tendinopathy of the rotator cuff: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 5; 1997:183-191.

5. McLaughlin HL. Lesions of the musculotendinous cuff of the shoulder. Observations on the pathology, course and treatment of calcific deposits. Ann Surg. 1946;124:354-362.

6. Painter C. Subdeltoid bursitis. Boston Med Surg J. 1907;156:345-349.

7. Codman EA. Calcified deposits in the supraspinatus. In: Codman EA, editor. The Shoulder: Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon and Other Lesions in or About the Subacromial Bursa. Boston: Thomas Todd; 1934:78-215.

8. Bosworth BM. Examination of the shoulder for calcium deposits. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:567-577.

9. Ross G, Cooper J, Minos L, Steinmann S Acute calcific tendinitis of the shoulder mimicking infection: arthroscopic evaluation and treatment—a case report. Am J Orthop, 35; 2006:572-574.

10. Neer CS. Less frequent procedures. In: Neer CS, editor. Shoulder Reconstruction. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:421-485.

11. DePalma AF, Kruper JS. Long-term study of shoulder joints afficted with and treated for calcific tendonitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1961;20:61-72.

12. Jim YF, Hsu HC, Chang CY, et al Coexistence of calcific tendinitis and rotator cuff tear: an arthrographic study. Skeletal Radiol, 22; 1993:183-185.

13. Bosworth BM Calcium deposits of the shoulder and subacromial bursitis: survey of 12122 shoulders. JAMA, 116; 1941:2477-2482.

14. Gaertner J. Tendinosis Calcarea-Behandlungsergebnisse mit dem needling. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1993;131:461-469.

15. Wolf WBIII. Shoulder tendinoses. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:871-890.

16. Lippmann RK. Observations concerning the calcific cuff deposit. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1961;20:49-60.

17. Robertson VJ, Baker KG A review of therapeutic ultrasound: effectiveness studies. Phys Ther, 81; 2001:1339-1350.

18. Ebenbichler GR, Erdogmus CB, Resch KL, et al. Ultrasound therapy for calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1533-1538.

19. Rokito AS, Loebenberg MI. Frozen shoulder and calcific tendonitis. Curr Opin Orthop. 1999;10:294-304.

20. Aina R, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ, et al Cacific shoulder tendinitis: treatment with modified US-guided fine needle technique. Radiology, 221; 2001:45-61.

21. Farin PU, Rasanen H, Jaroma H, Harju A Rotator cuff calcifications: treatment with US-guided percutaneous needle aspiration and lavage. Skeletal Radiol, 25; 1996:551-554.

22. Spindler A, Berman A, Lucero E, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave treatment for chronic calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1161-1163.

23. Loew M, Jurgowski W, Mau HC, et al Treatment of calcifying tendinitis of rotator cuff by extracorporeal shock waves: a preliminary report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 4; 1995:101-106.

24. Rompe JD, Zoellner J, Nafe B. Shock wave therapy versus conventional surgery in the treatment of calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;387:72-81.

25. Maier M, Stabler A, Lienemann A, et al. Shock wave application in calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder—prediction of outcome by imaging. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:493-498.

26. Wang C, Yang K, Wang F, et al. Shock wave therapy for calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:425-430.

27. Albert J, Meadeb J, Guggenbuhl P, et al. High-energy extracorporeal shock-wave therapy for calcifying tendinitis of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:335-341.

28. Hsu C, Wang D, Tseng K, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:55-59.

29. Ark JW, Flock TJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Arthroscopic treatment of calcific tendonitis of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:183-188.

30. Jerosch J, Strauss JM, Schmiel S. Arthroscopic treatment of calcific tendonitis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:30-37.

31. Molé D, Kempf J, Gleyse P, et al. Results of endoscopic treatment of non-broken tendinopathies of the rotator cuff. 2. Calcifications of the rotator cuff. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1993;79:532-541.

32. Seil R, Litzenburger H, Kohn D, Rupp S. Arthroscopic treatment of chronically painful calcifying tendinitis of the supraspinatus tendon. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:521-527.

33. Kayser R, Hampf S, Seeber E, Heyde C. Value of preoperative ultrasound marking of calcium deposits in patients who require surgical treatment of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:43-50.