C

Cachexia, see Malnutrition

• Indications include: previous CS; pre-existing maternal morbidity (e.g. cardiac disease); complications of pregnancy (e.g. pre-eclampsia); obstetric disorders (e.g. placenta praevia); fetal compromise; failure to progress.

• Specific anaesthetic considerations:

physiological changes of pregnancy.

physiological changes of pregnancy.

difficult tracheal intubation and aspiration of gastric contents associated with general anaesthesia (GA) have been major anaesthetic causes of maternal mortality. Mortality is higher for emergency CS than for elective CS.

difficult tracheal intubation and aspiration of gastric contents associated with general anaesthesia (GA) have been major anaesthetic causes of maternal mortality. Mortality is higher for emergency CS than for elective CS.

aortocaval compression must be minimised by avoiding the supine position at all times.

aortocaval compression must be minimised by avoiding the supine position at all times.

neonatal depression should be avoided, but maternal awareness may occur if depth of anaesthesia is inadequate.

neonatal depression should be avoided, but maternal awareness may occur if depth of anaesthesia is inadequate.

• The usual preoperative assessment should be made, with particular attention to:

the indication for CS (e.g. pre-eclampsia) and other obstetric or medical conditions.

the indication for CS (e.g. pre-eclampsia) and other obstetric or medical conditions.

whether CS is elective or emergency, and whether the fetus is compromised.

whether CS is elective or emergency, and whether the fetus is compromised.

maternal preference for general or regional anaesthesia.

maternal preference for general or regional anaesthesia.

if used in labour, the quality of existing epidural analgesia should be assessed.

if used in labour, the quality of existing epidural analgesia should be assessed.

assessment of the lumbar spine and any contraindications to regional anaesthesia.

assessment of the lumbar spine and any contraindications to regional anaesthesia.

• Regimens used to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonitis:

antacid therapy: 0.3 M sodium citrate (30 ml) directly neutralises gastric acidity; it has a short duration of action and should be given immediately before induction of anaesthesia.

antacid therapy: 0.3 M sodium citrate (30 ml) directly neutralises gastric acidity; it has a short duration of action and should be given immediately before induction of anaesthesia.

H2 receptor antagonists: different regimens are employed in different units, with most reserving prophylaxis, e.g. with ranitidine, for women at risk of operative intervention or receiving pethidine (causing reduced gastric emptying). For elective CS, ranitidine 150 mg orally the night before and 2 h before surgery is often given. For emergency CS, ranitidine 50 mg iv may be given; cimetidine 200 mg im is an alternative as it has a more rapid onset than ranitidine.

H2 receptor antagonists: different regimens are employed in different units, with most reserving prophylaxis, e.g. with ranitidine, for women at risk of operative intervention or receiving pethidine (causing reduced gastric emptying). For elective CS, ranitidine 150 mg orally the night before and 2 h before surgery is often given. For emergency CS, ranitidine 50 mg iv may be given; cimetidine 200 mg im is an alternative as it has a more rapid onset than ranitidine.

omeprazole and metoclopramide have also been used, to reduce gastric acidity and increase gastric emptying, respectively.

omeprazole and metoclopramide have also been used, to reduce gastric acidity and increase gastric emptying, respectively.

Sedative premedication is usually avoided because of the risk of neonatal respiratory depression and difficulties over timing.

– wide-bore iv access (16G or larger).

– cross-matched blood available within 30 min.

– routine monitoring and skilled anaesthetic assistance, with all necessary equipment and resuscitative drugs available and checked.

– ergometrine has been superseded by oxytocin as the first-line uterotonic following delivery because of the former’s side effects (e.g. hypertension and vomiting).

– rapid sequence induction with an adequate dose of anaesthetic agent is required to prevent awareness; a ‘maximal allowed dose’ based on weight may be insufficient. Neonatal depression due to iv induction agents is minimal. Suxamethonium is still considered the neuromuscular blocking drug of choice by most authorities, although rocuronium (especially with the advent of sugammadex) is an alternative.

– difficult and failed intubation (the latter ~1 : 300–500) is more likely in obstetric patients than in the general population. Contributory factors include a full set of teeth, increased fat deposition, enlarged breasts and the hand applying cricoid pressure hindering insertion of the laryngoscope blade into the mouth. Laryngeal oedema may be present in pre-eclampsia. Apnoea rapidly results in hypoxaemia because of reduced FRC and increased O2 demand.

– IPPV with 50% O2 in N2O is commonly recommended until delivery; however, in the absence of fetal distress, 33% O2 is associated with similar neonatal outcomes.

– 0.5–0.6 MAC of volatile agents (with 50% N2O) reduces the incidence of awareness to 1% without increasing uterine atony and bleeding, or neonatal depression; however, at 0.8–1.0 MAC, awareness falls to 0.2% and the uterus remains responsive to uterotonics. Placental blood flow is thought to be maintained by vasodilatation caused by the volatile agents, and high levels of vasoconstricting catecholamines associated with awareness are avoided. Delivery of higher concentrations of volatile agents (‘overpressure’) in 66% N2O has been suggested for the first 3–5 min whilst alveolar concentrations are low, to reduce awareness. Factors increasing the likelihood of awareness include lack of premedication, reduced concentrations of N2O and volatile agents, and withholding opioid analgesic drugs until delivery. Up to 26% awareness was reported in early studies using 50% N2O and no volatile anaesthetic agent.

– normocapnia (4 kPa/30 mmHg in pregnancy) is considered ideal; excessive hyperventilation may be associated with fetal hypoxaemia and acidosis due to placental vasoconstriction, impairment of O2 transfer associated with low PCO2, and reduced venous return caused by excessive IPPV.

– all neuromuscular blocking drugs cross the placenta to a very small extent. Shorter-acting drugs (e.g. vecuronium and atracurium), are usually employed, since postoperative residual paralysis associated with longer-lasting drugs has been a significant factor in some maternal deaths.

– opioid analgesic drugs are withheld until delivery of the infant, to avoid neonatal respiratory depression.

– advantages: usually quicker to perform in emergencies. May be used when regional techniques are inadequate or contraindicated, e.g. in coagulation disorders. Safer in hypovolaemia.

– disadvantages: risk of aspiration, difficult intubation, awareness and neonatal depression. Hypotension and reduced cardiac output may result from anaesthetic drugs and IPPV. Postoperative pain, drowsiness, PONV, blood loss and DVT risk all tend to be greater.

– facilities for GA should be available.

– bupivacaine 0.5% or lidocaine 2% (the latter with adrenaline 1 : 200 000) is most commonly used in the UK, often in combination. Addition of opioids (e.g. fentanyl) is common (though may not be necessary if many epidural doses have been given during labour). Bicarbonate has also been added to shorten the onset time, (e.g. 2 ml 8.4% added to 20 ml lidocaine or lidocaine/bupivacaine mixture), but risks errors from mixing up to 4–5 different drugs, especially in an emergency. Commercial premixed solutions of lidocaine/bupivacaine and adrenaline may be unsuitable as they have a low pH (3.5–5.5) and contain preservatives. Ropivacaine 0.5–0.75% or levobupivacaine 0.5% is also used. 0.75% bupivacaine is associated with a high incidence of toxicity, and has been withdrawn from obstetric use. Chloroprocaine is available in the USA and a small number of European countries (but not the UK); it has a rapid onset and offset. Etidocaine has also been used in the USA.

– L3–4 interspace is usually chosen.

– on average, 15–20 ml solution is required for adequate blockade (from S5 to T4–6). Loss of normal light touch sensation is a stronger predictor of intraoperative comfort than loss of cold sensation, although either may be used to assess the block. Smaller volumes are required for a specified level of block than in non-pregnant patients, as dilated epidural veins reduce the available volume in the epidural space.

– opioids (e.g. diamorphine 2–4 mg or fentanyl 50–100 µg) are routinely given epidurally for peri- and postoperative analgesia; maternal respiratory depression has been reported, albeit rarely.

– hypotension associated with blockade of sympathetic tone may be reduced by preloading with iv fluid; however, the use of vasopressors to prevent and treat hypotension in the euvolaemic patient is thought to be a more effective and rational approach. Ephedrine 3–6 mg or phenylephrine 50–100 µg is commonly given by intermittent bolus; continuous infusions are also effective. Phenylephrine appears to be associated with a better neonatal acid–base profile than large doses of ephedrine (thought to be due to ephedrine crossing the placenta and causing increased anaerobic glycolysis in the fetus via β-adrenergic stimulation).

– nausea and vomiting may be caused by hypotension and/or bradycardia.

– during surgery many women feel pressure and movement, which may be unpleasant; all women should be warned of this possibility and of the potential requirement for general anaesthesia. Inhaled N2O, further epidural top-ups, small doses of iv opioid drugs (e.g. fentanyl or alfentanil), iv paracetamol and ketamine may be useful. Shoulder tip pain may result from blood tracking up to the diaphragm and may be reduced by head-up tilt. Good communication between mother, anaesthetist and obstetrician is especially important when performing CS under regional anaesthesia, and the obstetrician should warn the anaesthetist before exteriorising the uterus or swabbing the paracolic gutters.

– disadvantages: risk of dural tap, total spinal blockade, local anaesthetic toxicity, severe hypotension. It may be slow to achieve adequate blockade with a risk of patchy block. Inability to move the legs may be disturbing.

spinal anaesthesia (SA):

spinal anaesthesia (SA):

– general considerations as for EA.

– 0.5% bupivacaine is used in the UK; plain bupivacaine (e.g. 3 ml) produces a more variable block than hyperbaric bupivacaine (e.g. 1.8–2.8 ml), which is the only form licensed for spinal anaesthesia. Plain levobupivacaine is also licensed in the UK. Hyperbaric tetracaine (amethocaine) 0.5% (1.2–1.6 ml) is used in the USA.

– injection is usually at the L3–4/L4–5 interspace.

– disadvantages: single shot; i.e. may not last long enough if surgery is prolonged. Spinal catheter techniques allow more control over spread and duration but are technically more difficult. Risk of post-dural puncture headache (reduced to under 1% if 25–27 G pencil-point needles are used). Hypotension is of faster onset and thus may be more difficult to control; has been associated with poorer neonatal acid–base status compared with EA/GA. Remains the most popular anaesthetic technique for CS in the UK.

combined spinal–epidural anaesthesia (CSE):

combined spinal–epidural anaesthesia (CSE):

– general considerations as for EA and SA.

– usually performed at a single vertebral interspace (needle-through-needle method)

(For contraindications and methods, see individual techniques)

See also, Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths; Fetus, effects of anaesthetic agents on; I–D interval; Induction, rapid sequence; Intubation, difficult; Intubation, failed; Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia; U–D interval

Caffeine. Xanthine present in tea, coffee and certain soft drinks; the world’s most widely used psychoactive substance. Also used as an adjunct to many oral analgesic drug preparations, although not analgesic itself. Causes CNS stimulation; traditionally thought to improve performance and mood, whilst reducing fatigue. Increases cerebral vascular resistance and decreases cerebral blood flow. Half-life is about 6 h. Has been used iv and orally for treatment of post-dural puncture headache. Acts via inhibition of phosphodiesterase, increasing levels of cAMP and as an antagonist at adenosine receptors.

• Side effects: as for aminophylline, especially CNS and cardiac stimulation.

Caisson disease, see Decompression sickness

Calcitonin. Hormone (mw 3500) secreted from the parafollicular (C) cells of the thyroid gland. Involved in calcium homeostasis; secretion is stimulated by hypercalcaemia, catecholamines and gastrin. Decreases serum calcium by inhibiting mobilisation of bone calcium, decreasing intestinal absorption and increasing renal calcium and phosphate excretion. Acts via a G protein-coupled receptor on osteoclasts. Calcitonin derived from salmon is used in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia, postmenopausal osteoporosis, Paget’s disease and intractable pain from bony metastases.

Calcium. 99% of body calcium is contained in bone; plasma calcium consists of free ionised calcium (50%) and calcium bound to proteins (mainly albumin) and other ions. The free ionised form is a second messenger in many cellular processes, including neuromuscular transmission, muscle contraction, coagulation, cell division/movement and certain oxidative pathways. Binds to intracellular proteins (e.g. calmodulin), causing configurational changes and enzyme activation. Intracellular calcium levels are much higher than extracellular, due to relative membrane impermeability and active transport mechanisms. Calcium entry via specific channels leads to direct effects (e.g. neurotransmitter release in neurones), or further calcium release from intracellular organelles (e.g. in cardiac and skeletal muscle). Extracellular hypocalcaemia has a net excitatory effect on nerve and muscle; hypocalcaemic tetany can result in life-threatening laryngospasm.

Ionised calcium increases with acidosis, and decreases with alkalosis. Thus for accurate measurement, blood should be taken without a tourniquet (which causes local acidosis), and without hyper-/hypoventilation. Ionised calcium is measured in some centres, but total plasma calcium is easier to measure; normal value is 2.12–2.65 mmol/l. Varies with the plasma protein level; corrected by adding 0.02 mmol/l calcium for each g/l albumin below 40 g/l, or subtracting for each g/l above 40 g/l.

vitamin D: group of related sterols. Cholecalciferol is formed in the skin by the action of ultraviolet light, and is converted in the liver to 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (in turn converted to 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the proximal renal tubules). Formation is increased by parathyroid hormone and decreased by hyperphosphataemia. Actions:

vitamin D: group of related sterols. Cholecalciferol is formed in the skin by the action of ultraviolet light, and is converted in the liver to 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (in turn converted to 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the proximal renal tubules). Formation is increased by parathyroid hormone and decreased by hyperphosphataemia. Actions:

– increases intestinal calcium absorption.

– increases renal calcium reabsorption.

– increases bone mineralisation.

parathyroid hormone: secretion is increased by hypocalcaemia and hypomagnesaemia, and decreased by hypercalcaemia and hypermagnesaemia. Actions:

parathyroid hormone: secretion is increased by hypocalcaemia and hypomagnesaemia, and decreased by hypercalcaemia and hypermagnesaemia. Actions:

– increases renal calcium reabsorption.

– increases renal phosphate excretion.

– increases formation of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol.

calcitonin: secreted by the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland. Secretion is increased by hypercalcaemia, catecholamines and gastrin. Actions:

calcitonin: secreted by the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland. Secretion is increased by hypercalcaemia, catecholamines and gastrin. Actions:

– decreases intestinal absorption of dietary calcium.

Calcium is used clinically to treat hypocalcaemia, e.g. during massive blood transfusion. It is also used as an inotropic drug. Although ionised calcium concentration may be low after cardiac arrest, its use during CPR is no longer recommended unless persistent hypocalcaemia, hyperkalaemia or overdose of calcium channel blocking drugs is involved. This is because of its adverse effects on ischaemic myocardium and on coronary and cerebral circulations.

Calcium channel blocking drugs. Structurally diverse group of drugs that block Ca2+ flux via specific Ca2+ channels (largely L-type, slow inward current). Effects vary according to relative affinity for cardiac or vascular smooth muscle Ca2+ channels.

• Classified according to pharmacological effects in vitro and in vivo:

class I: potent negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, e.g. verapamil. Acts mainly on the myocardium and conduction system; reduces myocardial contractility and O2 consumption and slows conduction of the action potential at the SA/AV nodes. Thus mainly used to treat angina and SVT (less useful in hypertension). Severe myocardial depression may occur, especially in combination with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists.

class I: potent negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, e.g. verapamil. Acts mainly on the myocardium and conduction system; reduces myocardial contractility and O2 consumption and slows conduction of the action potential at the SA/AV nodes. Thus mainly used to treat angina and SVT (less useful in hypertension). Severe myocardial depression may occur, especially in combination with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists.

– nifedipine: acts mainly on coronary and peripheral arteries, with little myocardial depression. Used in angina, hypertension and Reynaud’s syndrome. Systemic vasodilatation may cause flushing and headache, especially for the first few days of treatment.

– nicardipine: as nifedipine, but with even less myocardial depression.

– nimodipine: particularly active on cerebral vascular smooth muscle, it is used to relieve cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage.

class III: slight negative inotropic effects, without reflex tachycardia: diltiazem is used in angina and hypertension.

class III: slight negative inotropic effects, without reflex tachycardia: diltiazem is used in angina and hypertension.

The above drugs act mainly on the L-type calcium (long-lasting) channels; these are more widely distributed than the T-type (transient) channels which are confined to the sinoatrial node, vascular smooth muscle and renal neuroendocrine cells. N-type calcium channels are concentrated in neural tissue and are the binding site of omega toxins produced by certain venomous spiders and cone snails. A derivative of the latter, ziconotide, is available for the treatment of chronic pain.

Overdose causes hypotension, bradycardia and heart block. Treatment includes iv calcium chloride, glucagon and catecholamines. Heart block is usually resistant to atropine and hypotension may not respond to inotropes or vasopressors. High-dose insulin has been successful in reversing refractory hypotension.

Calcium resonium, see Polystyrene sulphonate resins

Calcium sensitisers. New class of inotropic drugs, now established as effective treatment of acute heart failure; examples include levosimendan and pimobendan. Act directly on cardiac myofilaments without increasing intracellular calcium, thus improving myocardial contractility without impairing ventricular relaxation. Levosimendan also has vasodilatory effects through opening of K+ channels.

Parissis JT, Rafouli-Stergiou P, Mebazaa A et al (2010). Curr Opin Crit Care; 16: 432–41

Calibration. Process of standardising the output of a measuring device against another measurement of known and constant magnitude. Reduces measurement error due to drift. One-point calibration is sufficient to address offset drift; two-point calibration is required for the mitigation of gradient drift. Essential for the accurate functioning of many measurement devices (e.g. arterial blood pressure monitor, blood gas analyser, expired gas analyser).

Calorie. Unit of energy. Although not an SI unit, widely used, especially when describing energy content of food.

1 cal = energy required to heat 1 g water by 1°C.

1 kcal (1 Cal) = energy required to heat 1 kg water by 1°C = 1000 cal.

Calorimetry, indirect, see Energy balance

CAM-ICU, see Confusion in the intensive care unit

Campbell–Howell method, see Carbon dioxide measurement

Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. Official journal of the Canadian Anesthetists’ Society. Launched in 1954 as the Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal. Became the Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia in 1987 and the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia in 1999.

Candela. SI unit of luminous intensity, one of the base (fundamental) units. Definition relates to the luminous intensity of a radiating black body at the freezing point of platinum.

Cannabis. Hallucinogenic drug obtained from the Cannabis sativa plant. A mixture of at least 60 chemicals (cannabinoids) including the main psychoactive δ-9-tetra-hydrocannibinol. Cannabinoid receptors have been identified in central and peripheral neurones (CB1 receptors) and lymphoid tissue (e.g. spleen) and macrophages (CB2); both types are G protein-coupled receptors.

Capacitance vessels. Composed of venae cavae and large veins; normally only partially distended, they may expand to accommodate a large volume of blood before venous pressure is increased. Innervated by the sympathetic nervous system in the same way as the arterial system (resistance vessels), they act as a blood reservoir. 60–70% of blood volume is within the veins normally.

Capacitor, see Capacitance

Capillary circulation. Contains 5% of circulating blood volume, which passes from arterioles to venules via capillaries, usually within 2 s. Controlled by local autoregulatory mechanisms, and possibly by autonomic neural reflexes. Substances that readily cross the capillary walls (mainly by diffusion) include water, O2, CO2, glucose and urea. Hydrostatic pressure falls from about 30 mmHg (arteriolar end) to 15 mmHg (venous end) within the capillary. Direction of fluid flow across capillary walls is determined by hydrostatic and osmotic pressure gradients (Starling forces).

Capnography. Continuous measurement and pictorial display of CO2 concentration (capnometry refers to measurement only). During anaesthesia, used to display end-tidal CO2; this may be achieved using:

The equipment used must have a very short response time in order to produce a continuous display (for uses and capnography traces, see Carbon dioxide, end-tidal).

Capreomycin. Cyclic polypeptide antibacterial drug used to treat TB resistant to other therapy (especially in immunocompromised patients). Also used in other mycobacterial infections. Poorly absorbed orally, peak levels occur within 2 h of im injection. Excreted unchanged in the urine.

Capsaicin. Component of hot chilli peppers; activates heat-sensitive Ca2+ channels (vanilloid receptors), located on Aδ and C pain fibres, producing a burning sensation. Initial stimulation is followed by depletion of substance P by reducing its synthesis, storage and transport. Applied topically for the treatment of neuralgias (e.g. postherpetic neuralgia) and arthritis. Should be applied 6–8-hourly. Takes 1–4 weeks to produce its effect. Application of a single high-concentration (8%) capsaicin patch can produce 3 months’ relief from neuropathic pain.

Captopril. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, used to treat hypertension and cardiac failure (including following MI), and diabetic nephropathy. Shorter acting than enalapril; onset is within 15 min, with peak effect at 30–60 min. Half-life is 2 h. Interferes with renal autoregulation; therefore contraindicated in renal artery stenosis or pre-existing renal impairment.

Carbamazepine. Anticonvulsant drug, used to treat all types of epilepsy, except petit mal. Acts by stabilising the inactivated state of voltage-gated sodium channels. Has fewer side effects than phenytoin, and has a greater therapeutic index. Also used for pain management (e.g. in trigeminal neuralgia) and in manic-depressive disease.

• Side effects: dizziness, visual disturbances, GIT upset, rash, hyponatraemia, cholestatic jaundice, hepatitis, syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion. Blood dyscrasias may occur rarely. Enzyme induction may cause reduced effects of other drugs, e.g. warfarin.

Contraindicated in atrioventricular conduction defects and porphyria.

Carbapenems. Group of bactericidal antibacterial drugs; contain the β-lactam ring and thus, like the penicillins, impair bacterial cell wall synthesis. Include imipenem, meropenem and ertapenem.

Carbetocin. Analogue of human oxytocin, licensed for prevention of uterine atony after delivery by caesarean section under regional anaesthesia. Acts within 2 min of injection, its effects lasting over an hour.

Carbicarb. Experimental buffer composed of 0.3 M sodium carbonate and 0.3 M sodium bicarbonate; unlike bicarbonate, there is no net generation of CO2, when treating acidosis.

Carbocisteine, see Mucolytic drugs

Carbohydrates (Saccharides). Class of compounds with the general formula Ca(H2O)b, hence their name, although they are not true hydrates. a usually exceeds 3, and may or not equal b. Notable examples of monosaccharides are ribose and glucose, where a = 5 and 6 respectively (pentoses and hexoses). Disaccharides are formed from condensation reactions between two monosaccharides (e.g. sucrose = glucose + fructose). Large polysaccharides include starch, cellulose and glycogen. Metabolites often contain phosphorus. Some polysaccharides are combined with proteins, e.g. mucopolysaccharides. Act as a source of energy in food, e.g.:

Carbon dioxide (CO2), Gas produced by oxidation of carbon-containing substances. Average rate of production under basal conditions in adults is about 200 ml/min, although it varies with the energy source (see Respiratory quotient).

Isolated in 1757 by Black. CO2 narcosis was used for anaesthesia in animals by Hickman in 1824. Used to stimulate respiration during anaesthesia in the early 1900s, to maintain ventilation and speed uptake of volatile agents during induction; also used to assist blind nasal tracheal intubation. Administration is now generally considered hazardous because of the adverse effects of hypercapnia; CO2 cylinders have now been largely removed from anaesthetic machines. Manufactured by heating calcium or magnesium carbonate, producing CO2 and calcium/magnesium oxide.

colourless gas, 1.5 times denser than air.

colourless gas, 1.5 times denser than air.

mw 44.

mw 44.

boiling point −79°C.

boiling point −79°C.

critical temperature 31°C.

critical temperature 31°C.

non-flammable and non-explosive.

non-flammable and non-explosive.

supplied in grey cylinders; pressure is 50 bar at 15°C, about 57 bar at room temperature.

supplied in grey cylinders; pressure is 50 bar at 15°C, about 57 bar at room temperature.

[Joseph Black (1728–1799), Scottish chemist]

See also, Acid–base balance; Alveolar gas transfer; Carbon dioxide absorption, in anaesthetic breathing systems; Carbon dioxide dissociation curve; Carbon dioxide, end-tidal; Carbon dioxide measurement; Carbon dioxide response curve; Carbon dioxide transport

Carbon dioxide absorption, in anaesthetic breathing systems. Investigated and described by Waters in the early 1920s, although used earlier. Exhaled gases are passed over soda lime or a similar material (e.g. baralyme) and reused. In closed systems, only basal O2 requirements need be supplied; absorption may also be used with low fresh gas flows and a leak through an expiratory valve.

less wastage of inhalational agent.

less wastage of inhalational agent.

warms and humidifies inhaled gases.

warms and humidifies inhaled gases.

if N2O is also used, risk of hypoxic gas mixtures makes an O2 analyser mandatory.

if N2O is also used, risk of hypoxic gas mixtures makes an O2 analyser mandatory.

failure of CO2 absorption may be due to exhaustion of soda lime or inefficient equipment; thus capnography is required.

failure of CO2 absorption may be due to exhaustion of soda lime or inefficient equipment; thus capnography is required.

resistance and dead space may be high with some systems, and inhalation of dust is possible.

resistance and dead space may be high with some systems, and inhalation of dust is possible.

trichloroethylene is incompatible with soda lime.

trichloroethylene is incompatible with soda lime.

chemical reactions between the volatile agent and soda lime if the latter dries out excessively (see Soda lime).

chemical reactions between the volatile agent and soda lime if the latter dries out excessively (see Soda lime).

• Methods:

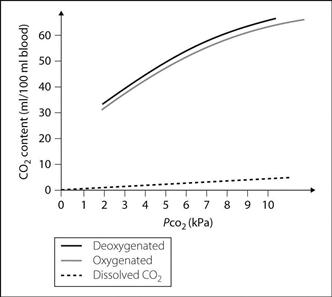

Carbon dioxide dissociation curve. Graph of blood CO2 content against its PCO2 (Fig. 29). The curve is much steeper than the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve, and more linear. Different curves are obtained for oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, the latter able to carry more CO2 (Haldane effect). The difference between the dissolved CO2 and the oxygenated haemoglobin curves represents the CO2 carried as bicarbonate ion and carbamino compounds.

Carbon dioxide, end-tidal. Partial pressure of CO2 measured in the final portion of exhaled gas. Approximates to alveolar PCO2 in normal anaesthetised subjects; the difference is normally 0.4–0.7 kPa (3–5 mmHg), increasing with  mismatch and increased CO2 production. Continuous monitoring (e.g. using infrared capnography or mass spectrometry) is considered mandatory during general anaesthesia.

mismatch and increased CO2 production. Continuous monitoring (e.g. using infrared capnography or mass spectrometry) is considered mandatory during general anaesthesia.

efficient cardiac massage or return of spontaneous cardiac output in CPR.

efficient cardiac massage or return of spontaneous cardiac output in CPR.

PE (including fat and air embolism): PECO2 falls due to increased alveolar dead space and reduced cardiac output.

PE (including fat and air embolism): PECO2 falls due to increased alveolar dead space and reduced cardiac output.

MH: PECO2 rises as muscle metabolism increases.

MH: PECO2 rises as muscle metabolism increases.

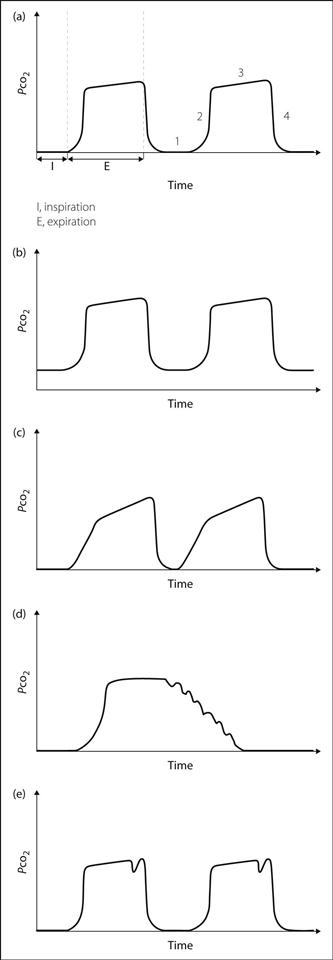

• Display of a continuous trace is more useful than values alone (Fig. 30a):

phase 1: zero baseline during inspiration; a raised baseline indicates rebreathing (Fig. 30b).

phase 1: zero baseline during inspiration; a raised baseline indicates rebreathing (Fig. 30b).

phase 2: dead-space gas (containing no CO2) is followed by alveolar gas, represented by a sudden rise to a plateau. Excessive sloping of the upstroke may indicate obstruction to expiration (Fig. 30c).

phase 2: dead-space gas (containing no CO2) is followed by alveolar gas, represented by a sudden rise to a plateau. Excessive sloping of the upstroke may indicate obstruction to expiration (Fig. 30c).

phase 3: near-horizontal plateau indicates mixing of alveolar gas. A steep upwards slope indicates obstruction to expiration or unequal mixing, e.g. COPD (Fig. 30c).

phase 3: near-horizontal plateau indicates mixing of alveolar gas. A steep upwards slope indicates obstruction to expiration or unequal mixing, e.g. COPD (Fig. 30c).

phase 4: rapid fall to zero at the onset of inspiration.

phase 4: rapid fall to zero at the onset of inspiration.

additional features may be present:

additional features may be present:

– superimposed regular oscillations corresponding to the heartbeat (Fig. 30d).

– small waves representing spontaneous breaths between ventilator breaths, e.g. if neuromuscular blockade is insufficient (Fig. 30e).

Carbon dioxide measurement. Estimation of arterial PCO2:

direct: Severinghaus CO2 electrode consisting of a glass pH electrode separated from arterial blood sample by a thin membrane. CO2 diffuses into bicarbonate solution surrounding the glass electrode, lowering pH. pH is measured and displayed in terms of PCO2. Requires maintenance at 37°C, and calibration with known mixtures of CO2/O2 before use. Samples are stored on ice or analysed immediately, to reduce inaccuracy due to blood cell metabolism.

direct: Severinghaus CO2 electrode consisting of a glass pH electrode separated from arterial blood sample by a thin membrane. CO2 diffuses into bicarbonate solution surrounding the glass electrode, lowering pH. pH is measured and displayed in terms of PCO2. Requires maintenance at 37°C, and calibration with known mixtures of CO2/O2 before use. Samples are stored on ice or analysed immediately, to reduce inaccuracy due to blood cell metabolism.

Indwelling intravascular CO2 electrodes are available for continuous monitoring of PCO2.

– end-tidal gas sampling (end-tidal PCO2 approximates to alveolar PCO2, which approximates to arterial PCO2).

– chemical: formation of non-gaseous compounds, with reduction of overall volume of the gas mixture (Haldane apparatus).

– physical: capnography and mass spectrometry are most widely used. An interferometer or gas chromatography may also be used.

– transcutaneous electrode: requires heating of the skin; relatively inaccurate and slowly responsive.

– measurement of venous PCO2 and capillary PCO2: inaccurate and unreliable.

– Siggaard-Andersen nomogram: equilibration of the blood sample with gases of known PCO2.

– van Slyke apparatus: liberation of gas from blood sample with subsequent chemical analysis.

Carbon dioxide narcosis. Loss of consciousness caused by severe hypercapnia, i.e. arterial PCO2 exceeding approximately 25 kPa (200 mmHg). Thought to be due to a profound fall in pH of CSF (under 6.9). Increasing central depression is seen at arterial PCO2 greater than 13 kPa (100 mmHg), and CSF pH under 7.1. Other features of hypercapnia may be present.

Used by Hickman in 1824 to enable painless surgery on animals.

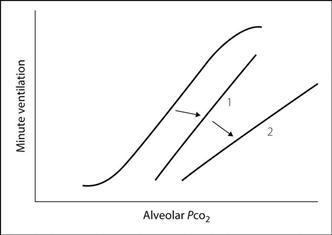

Carbon dioxide response curve. Graph defining the relationship between minute ventilation and arterial CO2 tension. May be obtained by rebreathing from a 6 litre bag containing 50% O2 and 7% CO2, measuring minute ventilation and bag PCO2 periodically. This is easier than increasing inspired CO2 levels and measuring the response after equilibration at each new level. The curve may be used to indicate depression of respiratory drive (Fig. 31); increased threshold is represented by a shift of the curve to the right (1), and decreased sensitivity by depression of the slope (2). Both may follow administration of opioid and other depressant drugs, and in chronic hypercapnia; the opposite occurs in hypoxaemia.

Carbon dioxide transport. In arterial blood, approximately 50 ml CO2 is carried per 100 ml blood, as:

bicarbonate: 45 ml.

bicarbonate: 45 ml.

carbamino compounds with proteins, mainly haemoglobin: 2.5 ml.

carbamino compounds with proteins, mainly haemoglobin: 2.5 ml.

CO2 is rapidly converted by carbonic anhydrase in red cells to carbonic acid, which dissociates to bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. Bicarbonate passes into plasma in exchange for chloride ions (chloride shift); hydrogen ions are buffered mainly by haemoglobin. Haemoglobin’s buffering ability increases as it becomes deoxygenated, as does its ability to form carbamino groups (Haldane effect).

See also, Acid–base balance; Buffers; Carbon dioxide dissociation curve

Carbon monoxide (CO). Colourless, odourless and tasteless gas produced by the partial oxidation of carbon-containing substances. Produced endogenously from the breakdown of haemoglobin, it acts as a neurotransmitter and may have a role in modulating inflammation and mitochondrial activity. Carbon monoxide poisoning may result from exposure to high levels of exogenous CO.

Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, see Diffusing capacity

Carbon monoxide poisoning. May result from inhalation of fumes from car exhausts, fires, heating systems or coal gas supplies. Often coexists with cyanide poisoning. Although not directly toxic to the lungs, carbon monoxide (CO) binds to haemoglobin with 200–250 times the affinity of O2, forming carboxyhaemoglobin, which dissociates very slowly. The amount of carboxyhaemoglobin formed depends on inspired CO concentration and duration of exposure.

Production of CO in circle systems has been reported under certain circumstances.

• Effects:

reduced capacity for O2 transport.

reduced capacity for O2 transport.

oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve shifted to the left.

oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve shifted to the left.

inhibition of the cellular cytochrome oxidase system; tissue toxicity is proportional to the length of exposure.

inhibition of the cellular cytochrome oxidase system; tissue toxicity is proportional to the length of exposure.

aortic and carotid bodies do not detect hypoxia, since the arterial PO2 is unaffected.

aortic and carotid bodies do not detect hypoxia, since the arterial PO2 is unaffected.

non-specific if chronic, e.g. headache, weakness, dizziness, GIT disturbances.

non-specific if chronic, e.g. headache, weakness, dizziness, GIT disturbances.

if acute: as above, with hypoxia, convulsions and coma if severe.

if acute: as above, with hypoxia, convulsions and coma if severe.

the ‘cherry red’ colour of carboxyhaemoglobin may be apparent.

the ‘cherry red’ colour of carboxyhaemoglobin may be apparent.

O2 saturation measured by pulse oximetry may be misleading because carboxyhaemoglobin (which has a unique spectrophotometric profile) is interpreted as oxygenated haemoglobin by some devices. Newer co-oximeters (e.g. Masimo Rainbow) are specifically able to determine blood carboxyhaemoglobin levels by measuring the absorbance of light across a range of wavelengths, thus distinguishing between different species of haemoglobin.

O2 saturation measured by pulse oximetry may be misleading because carboxyhaemoglobin (which has a unique spectrophotometric profile) is interpreted as oxygenated haemoglobin by some devices. Newer co-oximeters (e.g. Masimo Rainbow) are specifically able to determine blood carboxyhaemoglobin levels by measuring the absorbance of light across a range of wavelengths, thus distinguishing between different species of haemoglobin.

O2 therapy: speeds carboxyhaemoglobin dissociation. Tracheal intubation and IPPV may be necessary. Elimination half-life of carbon monoxide is reduced from 4 h to under 1 h with 100% O2; it is reduced further to under 30 min with hyperbaric O2 at 2.5–3 atm. At this pressure, dissolved O2 alone satisfies tissue O2 requirements. Hyperbaric O2 has been suggested if the patient is unconscious, has arrhythmias, is pregnant or has carboxyhaemoglobin levels above 40%.

O2 therapy: speeds carboxyhaemoglobin dissociation. Tracheal intubation and IPPV may be necessary. Elimination half-life of carbon monoxide is reduced from 4 h to under 1 h with 100% O2; it is reduced further to under 30 min with hyperbaric O2 at 2.5–3 atm. At this pressure, dissolved O2 alone satisfies tissue O2 requirements. Hyperbaric O2 has been suggested if the patient is unconscious, has arrhythmias, is pregnant or has carboxyhaemoglobin levels above 40%.

– 0.3–2%: normal non-smokers (some CO from pollution, some formed endogenously).

Hampson NB, Piantadosi CA, Thom SR, Weaver LK (2012). Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 186: 1095–101

Carbon monoxide transfer factor, see Diffusing capacity

Carbonic anhydrase. Zinc-containing enzyme catalysing the reaction of CO2 and water to form carbonic acid, which rapidly dissociates to bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. Absent from plasma, but present in high concentrations in:

Carboprost. Prostaglandin F2α analogue, used for the induction of second-trimester abortion; also used to treat postpartum haemorrhage unresponsive to first-line therapy. Given as the trometamol salt.

Carboxyhaemoglobin, see Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carcinogenicity of anaesthetic agents, see Environmental safety of anaesthetists; Fetus effects of anaesthetic agents on

Carcinoid syndrome. Results from secretion of vasoactive and other substances from certain tumours, found in the GIT (70%) or the bronchopulmonary system. Secreted compounds are metabolised by the liver so that symptoms are absent until hepatic metastases are present. May be associated with neurofibromatosis.

endocardial fibrosis involving the tricuspid and pulmonary valves may cause right-sided cardiac failure.

endocardial fibrosis involving the tricuspid and pulmonary valves may cause right-sided cardiac failure.

Symptoms are traditionally ascribed to secretion of 5-HT (diarrhoea) and kinins (flushing), but many more substances have been implicated, e.g. dopamine, substance P, prostaglandins, histamine and vasoactive intestinal peptide. Diagnosis includes measurement of urinary 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a breakdown product of 5-HT.

– somatostatin analogues, e.g. octreotide: inhibits release of inflammatory mediators and has become the first-line treatment of many authorities.

– 5-HT antagonists: ketanserin, cyproheptadine, methysergide.

invasive cardiovascular monitoring and careful fluid balance.

invasive cardiovascular monitoring and careful fluid balance.

use of cardiostable drugs where possible; avoidance of drugs causing histamine release.

use of cardiostable drugs where possible; avoidance of drugs causing histamine release.

suxamethonium has been claimed to increase mediator release via fasciculations but this is uncertain.

suxamethonium has been claimed to increase mediator release via fasciculations but this is uncertain.

drugs should be prepared for treatment of bronchospasm and hyper-/hypotension.

drugs should be prepared for treatment of bronchospasm and hyper-/hypotension.

Kinney MA, Warner ME, Nagorney DM, et al (2001). Br J Anaesth; 87: 447–52

Cardiac arrest. Sudden circulatory standstill. Common cause of death in cardiovascular disease, especially ischaemic heart disease. May also be caused by PE, electrolyte disturbances (e.g. of potassium or calcium), hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, hypotension, vagal reflexes, hypothermia, anaphylaxis, electrocution, drugs (e.g. adrenaline) and instrumentation of the heart.

VF: usually associated with myocardial ischaemia. The most common ECG finding (about 60%), with the best prognosis.

VF: usually associated with myocardial ischaemia. The most common ECG finding (about 60%), with the best prognosis.

asystole: occurs in about 30%. More likely in hypovolaemia and hypoxia, especially in children. May also follow vagally mediated bradycardia.

asystole: occurs in about 30%. More likely in hypovolaemia and hypoxia, especially in children. May also follow vagally mediated bradycardia.

electromechanical dissociation (EMD)/pulseless electrical activity (PEA). May occur in widespread myocardial damage. The least common ECG finding, with the worst prognosis, unless due to mechanical causes of circulatory collapse, e.g. PE, cardiac tamponade, pneumothorax.

electromechanical dissociation (EMD)/pulseless electrical activity (PEA). May occur in widespread myocardial damage. The least common ECG finding, with the worst prognosis, unless due to mechanical causes of circulatory collapse, e.g. PE, cardiac tamponade, pneumothorax.

Asystole and EMD/PEA may convert to VF, which eventually converts to asystole if untreated.

Only 15–20% of patients leave hospital after cardiac arrest. Up to 30–40% survival is thought to be possible if prompt CPR is instituted. Permanent hypoxic brain damage usually occurs within 4–5 min unless CPR is instituted. The prognosis is better if the patient regains consciousness within 10 min of the circulation restarting.

See also, Advanced life support, adult; Basic life support, adult; Cerebral ischaemia

Cardiac asthma. Acute pulmonary oedema resembling asthma. Both may feature dyspnoea, decreased lung compliance and widespread rhonchi, although pink frothy sputum is suggestive of pulmonary oedema. Increased airway resistance may result from true bronchospasm or from bronchial oedema.

Cardiac catheterisation. Passage of a catheter into the heart chambers for measurement of intracardiac pressures and O2 saturations, or for injection of radiological contrast media for radiological imaging (angiocardiography). Used to investigate ischaemic heart disease, valvular heart disease and congenital heart disease; also used therapeutically (e.g. balloon valvotomy, atrial septostomy for transposition of the great arteries and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty).

access is via a peripheral vein or artery, e.g. femoral or brachial vessels, using either a cut-down technique or percutaneous guidewire (Seldinger technique).

access is via a peripheral vein or artery, e.g. femoral or brachial vessels, using either a cut-down technique or percutaneous guidewire (Seldinger technique).

the right side of the heart is approached as for pulmonary artery catheterisation.

the right side of the heart is approached as for pulmonary artery catheterisation.

pressure values, waveforms and gradients between chambers.

pressure values, waveforms and gradients between chambers.

saturation values; greater than expected values on the right side indicate a left-to-right shunt.

saturation values; greater than expected values on the right side indicate a left-to-right shunt.

cardiac output may be measured using the Fick principle.

cardiac output may be measured using the Fick principle.

Approximate normal pressures and measurements are shown in Table 14.

Table 14 Normal pressures and O2 saturations obtained during cardiac catheterisation

| Site | Pressure (mmHg) | Saturation (%) |

| Right atrium | 1–4 | 75 |

| Right ventricle | 25/4 | 75 |

| Pulmonary artery | 25/12 | 75 |

| Left atrium | 2–10 | 97 |

| Left ventricle | 120/10 | 97 |

| Aorta | 120/70 | 97 |

Fig. 32 Cardiac cycle (see text)

Cardiac compressions, see Cardiac massage

Cardiac contractility, see Myocardial contractility

Cardiac cycle. Sequence of events occurring during cardiac activity; often represented by the Wiggers’ diagram, which details changes in vascular pressures (especially arterial BP), heart chamber pressures, ECG and phonocardiography tracings during normal sinus rhythm (Fig. 32).

phase 4: isometric ventricular relaxation: lasts until the tricuspid and mitral valves open.

phase 4: isometric ventricular relaxation: lasts until the tricuspid and mitral valves open.

phase 5: passive ventricular filling: most rapid at the start of diastole.

phase 5: passive ventricular filling: most rapid at the start of diastole.

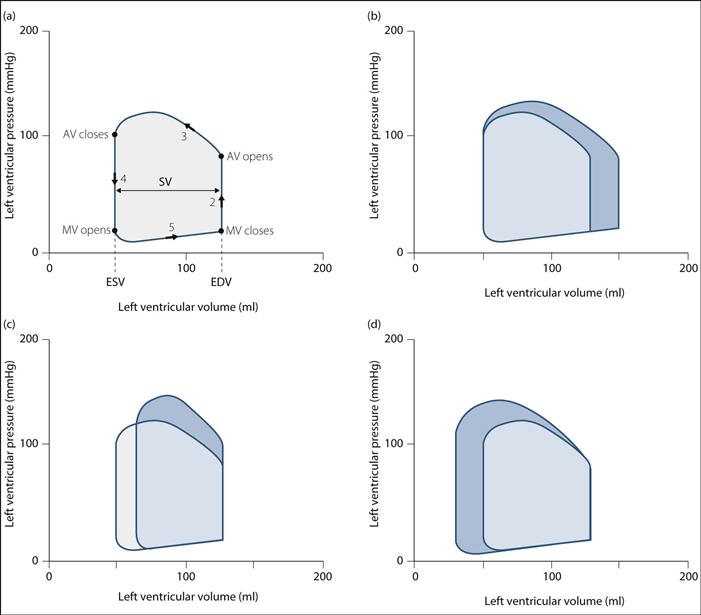

• May also be described in terms of the changes in pressure and volume within the left ventricle during the cardiac cycle – the left ventricular pressure–volume ‘loop’ (Fig. 33):

consists of four phases corresponding to phases 2–5 of the Wigger’s diagram, as described above – the transition between phases is marked by opening/closure of mitral/aortic valves (MV/AV) (Fig. 33a).

consists of four phases corresponding to phases 2–5 of the Wigger’s diagram, as described above – the transition between phases is marked by opening/closure of mitral/aortic valves (MV/AV) (Fig. 33a).

stroke volume (SV) is the difference between end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV).

stroke volume (SV) is the difference between end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV).

stroke work corresponds to the area within the loop.

stroke work corresponds to the area within the loop.

changes in preload, afterload and myocardial contractility result in predictable changes in the shape of the loop, with corresponding changes in SV and work (Fig. 33b–d):

changes in preload, afterload and myocardial contractility result in predictable changes in the shape of the loop, with corresponding changes in SV and work (Fig. 33b–d):

– increased preload or EDV results in increased force of contraction (see Starling’s law); SV and work increase.

– increased afterload results in increased ESV; SV decreases.

– increased contractility results in decreased ESV; stroke volume and work are increased.

Cardiac enzymes. Enzymes normally within cardiac cells; released into the blood after injury (e.g. after MI or cardiac contusion), thus aiding diagnosis:

– rises 4–6 h after MI, peaks at 12 h, falls at 2–3 days.

aspartate aminotransferase (AST):

aspartate aminotransferase (AST):

– rises after 12 h, peaks at 1–2 days.

– normally < 300 iu/l (depends on the assay).

– rises after 12 h, peaks at 2–3 days, falls after 5–7 days.

Have been largely replaced by troponins as indicators of myocardial damage (see Acute coronary syndromes).

Cardiac failure. Usually defined as inability of the heart to produce sufficient output for the body’s requirements. The diagnosis is clinical, ranging from mild symptoms on exertion only to cardiogenic shock. Several terms have been used to describe different forms of cardiac failure:

forward or backward failure: the former refers to failure with reduced cardiac output; the latter refers to failure with venous congestion.

forward or backward failure: the former refers to failure with reduced cardiac output; the latter refers to failure with venous congestion.

high-output failure: associated with increased preload and increased cardiac output.

high-output failure: associated with increased preload and increased cardiac output.

diastolic failure: recently recognised form in which the ejection fraction may be normal but ventricular filling is impaired.

diastolic failure: recently recognised form in which the ejection fraction may be normal but ventricular filling is impaired.

– preload:

– aortic/mitral regurgitation.

– severe anaemia, fluid overload, hyperthyroidism.

– pulmonary/aortic stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

– MI, ischaemic heart disease.

– cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis (right side).

– reduced ventricular compliance, e.g. amyloid infiltration.

• Effects:

ventricular end-diastolic pressure increases, leading to compensatory mechanisms:

ventricular end-diastolic pressure increases, leading to compensatory mechanisms:

– increased force of contraction (Starling’s law).

– neuroendocrine response: mainly increased sympathetic activity, with tachycardia, vasoconstriction and increased contractility. Aldosterone, renin/angiotensin and vasopressin activity are increased, especially in chronic failure, but mechanisms are unclear. Salt and water retention result.

ventricular compliance is reduced, leading to increased atrial pressure and atrial hypertrophy. Eventually, ventricular dilatation occurs, with higher wall tension required to produce a given pressure (Laplace’s law).

ventricular compliance is reduced, leading to increased atrial pressure and atrial hypertrophy. Eventually, ventricular dilatation occurs, with higher wall tension required to produce a given pressure (Laplace’s law).

coronary blood flow is reduced by tachycardia, raised end-diastolic pressure and increased muscle mass.

coronary blood flow is reduced by tachycardia, raised end-diastolic pressure and increased muscle mass.

left-sided failure may lead to pulmonary oedema, pulmonary hypertension,

left-sided failure may lead to pulmonary oedema, pulmonary hypertension,  mismatch, decreased lung compliance and right-sided failure.

mismatch, decreased lung compliance and right-sided failure.

right ventricular failure: CVP and JVP increase, with peripheral oedema and hepatic engorgement.

right ventricular failure: CVP and JVP increase, with peripheral oedema and hepatic engorgement.

reduced peripheral blood flow leads to increased O2 uptake and reduction of mixed venous PO2.

reduced peripheral blood flow leads to increased O2 uptake and reduction of mixed venous PO2.

sodium and water retention exacerbate oedema.

sodium and water retention exacerbate oedema.

reduced cardiac output may result in hypotension, confusion and coma.

reduced cardiac output may result in hypotension, confusion and coma.

– peripheral shutdown, basal crepitations, left ventricular hypertrophy. Extra heart sounds, e.g. gallop rhythm and heart murmurs, may be present. Cheyne–Stokes respiration may accompany low output.

– dependent oedema, e.g. ankles if ambulant, sacrum if bed-bound.

– hepatomegaly/ascites; the liver may be tender.

– right ventricular hypertrophy.

CXR may reveal cardiomegaly, upper-lobe blood diversion, fluid in the pulmonary fissures, Kerley lines, pleural effusion and pulmonary oedema. ECG may reveal ventricular hypertrophy and strain and arrhythmias.

CXR may reveal cardiomegaly, upper-lobe blood diversion, fluid in the pulmonary fissures, Kerley lines, pleural effusion and pulmonary oedema. ECG may reveal ventricular hypertrophy and strain and arrhythmias.

general: of underlying cause, rest, sodium restriction; O2 therapy if acute.

general: of underlying cause, rest, sodium restriction; O2 therapy if acute.

ACE inhibitors: inhibit ventricular remodelling, reducing mortality and morbidity. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists have similar efficacy.

ACE inhibitors: inhibit ventricular remodelling, reducing mortality and morbidity. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists have similar efficacy.

diuretics: reduce salt and water retention, providing symptomatic relief; a thiazide in combination with a loop diuretic is frequently used. Spironolactone may be added in low dosage to ACE inhibitor/diuretic therapy in severe, non-responsive failure.

diuretics: reduce salt and water retention, providing symptomatic relief; a thiazide in combination with a loop diuretic is frequently used. Spironolactone may be added in low dosage to ACE inhibitor/diuretic therapy in severe, non-responsive failure.

β-adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g. carvedilol, bisoprolol): first-line agents in stable left ventricular systolic failure, reducing mortality and morbidity.

β-adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g. carvedilol, bisoprolol): first-line agents in stable left ventricular systolic failure, reducing mortality and morbidity.

other vasodilator drugs (e.g. nitrates, hydralazine) have been used in patients unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.

other vasodilator drugs (e.g. nitrates, hydralazine) have been used in patients unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.

inotropic drugs: oral drugs are mostly disappointing. The most effective drugs are administered by iv infusion.

inotropic drugs: oral drugs are mostly disappointing. The most effective drugs are administered by iv infusion.

digoxin: may improve symptoms and performance but not mortality.

digoxin: may improve symptoms and performance but not mortality.

calcium sensitisers, e.g. levosimendan.

calcium sensitisers, e.g. levosimendan.

atrial-synchronised biventricular pacemakers have been shown to improve symptoms and mortality in patients with severe failure.

atrial-synchronised biventricular pacemakers have been shown to improve symptoms and mortality in patients with severe failure.

emergency treatment: as for pulmonary oedema and cardiogenic shock.

emergency treatment: as for pulmonary oedema and cardiogenic shock.

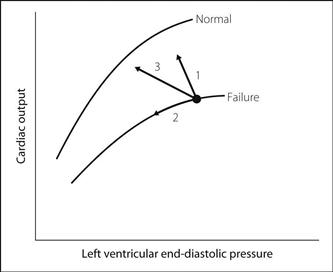

• Response to treatment (Fig. 34):

1: inotropic drugs/arterial vasodilators.

1: inotropic drugs/arterial vasodilators.

2: diuretics/venous vasodilators.

2: diuretics/venous vasodilators.

– drug combinations, e.g. inotropes + vasodilators; often produce the greatest improvement

– intra-aortic counter-pulsation balloon pump.

treatment as above. Electrolyte disturbances and digoxin toxicity may occur.

treatment as above. Electrolyte disturbances and digoxin toxicity may occur.

anaesthetic drugs should be given in small doses and slowly, because:

anaesthetic drugs should be given in small doses and slowly, because:

– arm–brain circulation time is increased.

Cardiac glycosides. Drugs derived from plant extracts; used to control ventricular rate in atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter and for symptomatic relief in cardiac failure. Actions are due to inhibition of the sodium/potassium pump and increased calcium mobilisation. The drugs have long half-lives (e.g. ouabain 20 h; digoxin 36 h; digitoxin 4 days), large volumes of distribution (e.g. digoxin 700 litres) and low therapeutic index.

• Actions:

increase myocardial contractility and stroke volume.

increase myocardial contractility and stroke volume.

• Side effects: as for digoxin. They are increased by hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia and hypomagnesaemia. Toxicity is also more likely in renal failure and pulmonary disease.

Digoxin is most widely used. Ouabain is more rapidly acting.

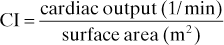

Cardiac index (CI). Cardiac output corrected for body size, expressed in terms of body surface area:

Cardiac massage. Periodic compression of the heart or chest in order to maintain cardiac output, e.g. during CPR. Both open (internal) and closed (external) cardiac massage were developed in the late 1800s. The latter became more popular in the 1960s following clear demonstration of its value in dogs and humans, and was subsequently adopted by the American Heart Association and the Resuscitation Council (UK) as method of choice.

Technique in children up to 8 years:

Technique in children up to 8 years:

theories of mechanism (both may occur):

theories of mechanism (both may occur):

– thoracic pump: the theory arose from arterial and cardiac chamber pressure measurements during CPR, and from the phenomenon of cough–CPR. Positive intrathoracic pressure pushes blood out of heart and chest during compressions; reverse flow is prevented by cardiac and venous valves, and collapse of the thin-walled veins. During relaxation, blood is drawn into the chest by negative intrathoracic pressure.

– automatic chest compressor (‘chest thumper’).

Improved blood flows and outcome have been claimed but further studies are awaited.

increasingly used, because blood flows and cardiac output are greater than with closed massage. Also, direct vision and palpation are useful in assessing cardiac rhythm and filling, and defibrillation and intracardiac injection are easier.

increasingly used, because blood flows and cardiac output are greater than with closed massage. Also, direct vision and palpation are useful in assessing cardiac rhythm and filling, and defibrillation and intracardiac injection are easier.

may also be performed per abdomen through the intact diaphragm; the heart is compressed against the sternum. Minimally invasive direct cardiac massage via a small thoracostomy has recently been described.

may also be performed per abdomen through the intact diaphragm; the heart is compressed against the sternum. Minimally invasive direct cardiac massage via a small thoracostomy has recently been described.

European Resuscitation Council (2010). Resuscitation; 81: 1219–76

Cardiac output (CO). Volume of blood ejected by the left ventricle into the aortic root per minute. Equals stroke volume (litres) × heart rate (beats/min). Normally about 5 l/min (0.07 litres × 70 beats/min) in a fit 70-kg man at rest; may increase up to 30 l/min, e.g. on vigorous exercise. Often corrected for body surface area (cardiac index).

Of central importance in maintaining arterial BP (equals cardiac output × SVR) and O2 delivery to the tissues (O2 flux).

Affected by metabolic rate (e.g. increased in pregnancy, sepsis, hyperthyroidism and exercise), drugs, and many other physiological and pathological processes that affect heart rate, preload, myocardial contractility and afterload.