Chapter 51 Burns and Smoke Inhalation

BURNS

1 How common are burns and fire-related deaths among children?

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: www.cdc.gov/ncipc

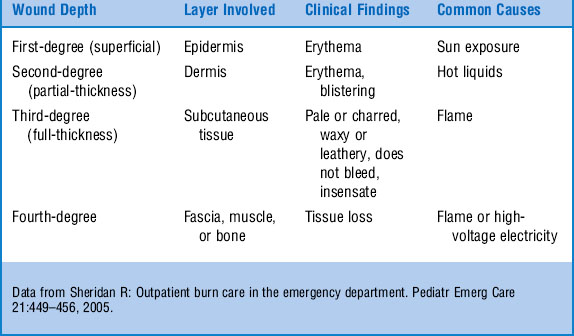

4 What are the common sources of burns in children?

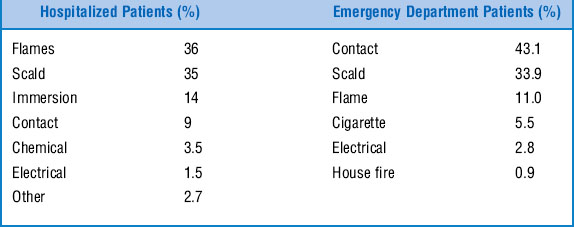

The cause of burns in children varies with the setting in which they are evaluated and the age of the child (Table 51-2). Common burns treated in an emergency department (ED) differ from those requiring hospitalization. Contact and scald burns make up a higher proportion of burns treated on an outpatient basis. The true pattern of burn injuries in children, including those not seeking medical care, may be substantially different. Scald burns predominate in the younger age group. Most of these occur when the child pulls over a hot liquid from the surface of a table or stove. Burns due to flames account for most hospital admissions in older children.

5 How long must the skin be in contact with hot water to cause a burn?

| Temperature | Time |

|---|---|

| 160°F | 1 seconds |

| 150°F | 2 seconds |

| 140°F | 5 seconds |

| 130°F | 30 seconds |

| 120°F | 300 seconds |

6 Why is it important to interview the paramedics who arrive with fire victims?

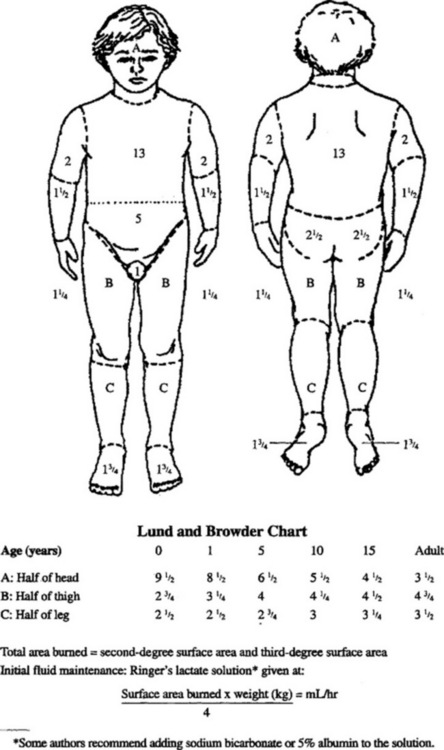

7 Name the methods commonly used to estimate the percentage of body surface area (BSA) damaged by burns in a child

The distribution of BSA is different in children and adults. The standard “rule of nines” used in adults is not as accurate in children. The young child has a greater proportion of the BSA in the head and less in the lower extremities. Nagel and Schunk demonstrated that the entire palmar surface of a child’s hand (including the fingers) is approximately 1% of BSA. The Lund and Browder chart (Fig. 51-1) provides useful estimates of larger contiguous burn areas in children younger than 10 years of age. First-degree burns are not generally included in the calculation of total BSA burned.

Lund C, Browder N: The estimation of areas of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet 79:352–358, 1944.

8 What is the initial treatment of major burns in a child?

1 Address and stabilize the airway, breathing, and circulation.

2 Remove clothing and any remaining hot or burning material.

3 Obtain IV access and begin fluid resuscitation, as needed, for severe burns.

5 Monitor and maintain core temperature.

6 Assess the extent and depth of burns.

7 Irrigate with lukewarm sterile saline.

8 Gently remove devitalized tissue with sterile gauze.

9 Perform escharotomies, as needed, for full-thickness circumferential burns.

10 Apply topical antibiotics to partial-thickness burns.

11 Cover large burn areas with sterile sheets.

9 Name some recommended topical therapies for burns

Bacitracin ointment—burns on the face

Bacitracin ointment—burns on the face

Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment—burns around the eye

Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment—burns around the eye

1% silver sulfadiazine cream—burns on the body

1% silver sulfadiazine cream—burns on the body

11.1% mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon)—burns on the external ear. Mafenide acetate penetrates the burn eschar to reach and protect the cartilage of the ear.

11.1% mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon)—burns on the external ear. Mafenide acetate penetrates the burn eschar to reach and protect the cartilage of the ear.

Synthetic membranes are also available to cover burn wounds. These dressings do not require daily changes but are much more expensive.

Synthetic membranes are also available to cover burn wounds. These dressings do not require daily changes but are much more expensive.

Monafo WW: Current concepts: Initial management of burns. N Engl J Med 335:1581–1586, 1996.

10 How should blisters be treated?

Reed JL, Pomerantz WJ: Emergency management of pediatric burns. Pediatr Emerg Care 21:118–129, 2005.

12 What are the indications for referral to a regional burn center?

Burns accompanied by respiratory injuries or major trauma

Burns accompanied by respiratory injuries or major trauma

Major chemical or electrical burns

Major chemical or electrical burns

Partial-thickness and full-thickness burns covering over 10% BSA in children under 10 years of age, or over 20% in children older than 10 years

Partial-thickness and full-thickness burns covering over 10% BSA in children under 10 years of age, or over 20% in children older than 10 years

Full-thickness burns over 2% BSA

Full-thickness burns over 2% BSA

Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical conditions affecting management or prognosis

Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical conditions affecting management or prognosis

Burn injury in patients requiring special social, emotional, or long-term rehabilitative intervention

Burn injury in patients requiring special social, emotional, or long-term rehabilitative intervention

13 A 15-year-old male presents with circumoral burns consistent with frostbite injury. What should you suspect?

14 Describe the patterns of burns commonly associated with child abuse

Immersion burns. This pattern of injury occurs as the result of a body part being dipped in a hot liquid. These burns are often circumferential with a sharply demarcated border. Burns in a glove-and-stocking distribution are a classic example.

Immersion burns. This pattern of injury occurs as the result of a body part being dipped in a hot liquid. These burns are often circumferential with a sharply demarcated border. Burns in a glove-and-stocking distribution are a classic example.

Doughnut burn. This term describes the sparing of the central area of the buttocks when it is held in contact with the cooler ceramic of the bathtub floor. The surrounding areas of skin remain in contact with the water and sustain more severe burns. Burns involving the genitals, the buttocks, or perineum are unlikely to be accidental.

Doughnut burn. This term describes the sparing of the central area of the buttocks when it is held in contact with the cooler ceramic of the bathtub floor. The surrounding areas of skin remain in contact with the water and sustain more severe burns. Burns involving the genitals, the buttocks, or perineum are unlikely to be accidental.

Contact burns on the dorsum of the hands. Children are more likely to sustain accidental burns by reaching for hot objects and grasping them with the palmar surface.

Contact burns on the dorsum of the hands. Children are more likely to sustain accidental burns by reaching for hot objects and grasping them with the palmar surface.

Markings consistent with an object, such as a cigarette or iron, held to the skin.

Markings consistent with an object, such as a cigarette or iron, held to the skin.

SMOKE INHALATION

16 What are the indications for intubation of the trachea of a fire victim?

Early-onset stridor. The presence of stridor or hoarseness suggests upper airway injury that can be expected to progress. Laryngeal edema does not peak until 2–8 hours after exposure. Intubation for this cause frequently requires an endotracheal tube with a smaller internal diameter than standard calculations suggest because of airway swelling.

Early-onset stridor. The presence of stridor or hoarseness suggests upper airway injury that can be expected to progress. Laryngeal edema does not peak until 2–8 hours after exposure. Intubation for this cause frequently requires an endotracheal tube with a smaller internal diameter than standard calculations suggest because of airway swelling.

Severe burns of the face or mouth. Patients are at significant risk for upper and lower airway injury.

Severe burns of the face or mouth. Patients are at significant risk for upper and lower airway injury.

Progressive respiratory insufficiency. Respiratory insufficiency may be diagnosed clinically or by the finding of a widening arterial-alveolar gradient or rising levels of partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Hypercarbia may result from depressed mental status, pain associated with chest wall movement, restriction of chest wall movement secondary to burns, pulmonary restrictive or obstructive injury, or upper airway swelling and obstruction.

Progressive respiratory insufficiency. Respiratory insufficiency may be diagnosed clinically or by the finding of a widening arterial-alveolar gradient or rising levels of partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Hypercarbia may result from depressed mental status, pain associated with chest wall movement, restriction of chest wall movement secondary to burns, pulmonary restrictive or obstructive injury, or upper airway swelling and obstruction.

Inability to protect the airway due to coma or profuse tracheobronchial secretions.

Inability to protect the airway due to coma or profuse tracheobronchial secretions.

Carboxyhemoglobin levels > 50. Intubation and active ventilation provide increased oxygen concentrations and help to decrease levels more rapidly.

Carboxyhemoglobin levels > 50. Intubation and active ventilation provide increased oxygen concentrations and help to decrease levels more rapidly.

18 What precautions must be taken when interpreting an arterial blood gas sample from a victim of smoke inhalation?

20 How is the half-life of carboxyhemoglobin affected at different oxygen concentrations?

23 What are the criteria for hyperbaric oxygen therapy?

Severe neurologic symptoms on presentation (seizures, focal neurologic findings, coma)

Severe neurologic symptoms on presentation (seizures, focal neurologic findings, coma)

Myocardial ischemia diagnosed by history or electrocardiography

Myocardial ischemia diagnosed by history or electrocardiography

Cardiac dysrhythmias (ventricular, life-threatening)

Cardiac dysrhythmias (ventricular, life-threatening)

Persistent neurologic symptoms and signs after several hours of 100% oxygen therapy at ambient pressure (mental confusion, visual disturbance, ataxia)

Persistent neurologic symptoms and signs after several hours of 100% oxygen therapy at ambient pressure (mental confusion, visual disturbance, ataxia)

Pregnancy (symptomatic, carboxyhemoglobin level > 15%, evidence of fetal distress)

Pregnancy (symptomatic, carboxyhemoglobin level > 15%, evidence of fetal distress)

Carboxyhemoglobin level > 20–25%

Carboxyhemoglobin level > 20–25%

Abnormal results on neuropsychological examination

Abnormal results on neuropsychological examination

Age < 6 months with symptoms (lethargy, irritability, poor feeding) or involved in same exposure as adults with any of the above criteria

Age < 6 months with symptoms (lethargy, irritability, poor feeding) or involved in same exposure as adults with any of the above criteria

Children who have underlying diseases (i.e., sickle cell anemia) for whom hypoxia may have deleterious effects

Children who have underlying diseases (i.e., sickle cell anemia) for whom hypoxia may have deleterious effects

24 List the major therapeutic actions of hyperbaric oxygen

27 What treatments are available for cyanide poisoning?

Sodium thiosulfate can be administered intravenously as an infusion of a 25% solution of sodium thiosulfate at a dose of 1.65 mL/kg. It is the rate-limiting compound in the conversion of cyanide to thiocyanate, which is excreted harmlessly in the urine.

Sodium thiosulfate can be administered intravenously as an infusion of a 25% solution of sodium thiosulfate at a dose of 1.65 mL/kg. It is the rate-limiting compound in the conversion of cyanide to thiocyanate, which is excreted harmlessly in the urine.

Amyl nitrate and sodium nitrate convert hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which preferentially binds cyanide in the form of cyanmethemoglobin. This therapy is generally not recommended for smoke inhalation because it further reduces the level of normal hemoglobin in fire victims who already have a significant amount of dysfunctional hemoglobin.

Amyl nitrate and sodium nitrate convert hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which preferentially binds cyanide in the form of cyanmethemoglobin. This therapy is generally not recommended for smoke inhalation because it further reduces the level of normal hemoglobin in fire victims who already have a significant amount of dysfunctional hemoglobin.

Hydroxocobalamin is used to treat cyanide poisoning in Europe but is not available for this use in the United States.

Hydroxocobalamin is used to treat cyanide poisoning in Europe but is not available for this use in the United States.

Kulig K: Cyanide antidotes and fire toxicology. N Engl J Med 325:1801–1802, 1991.

28 What is the role of steroids in the setting of smoke inhalation?

Ruddy RM: Smoke inhalation injury. Pediatr Clin North Am 41:317–336, 1994.

30 What is the most effective measure in reducing mortality from burns and smoke inhalation?

Anticipatory guidance and preventive care have the greatest potential to reduce deaths from burns and house fires. It is estimated that over 50% of fire-related deaths could be avoided with the proper use of smoke detectors. Over 90% of childhood deaths from fires occur in homes without properly functioning smoke detectors, and most children in house fires die from smoke inhalation rather than burns. Smoke detectors should be installed on every level of the house and tested regularly. Batteries should be replaced twice a year. Families should be educated about the planning of escape routes, evaluating fire risks in the house and in the use and storage of fire extinguishers. Careless (or any) cigarette use should be avoided. Lowering the setting on the water heater to deliver water at a maximum temperature of 120°F (48.8° C) substantially increases the time it takes for direct exposure to induce a full-thickness burn (see question 5). Boiling liquids should be placed on the back burners of the stove where they are out of the reach of young children. Children should be dressed in flame-retardant sleepwear.