Chapter 31. Burns

The following information should be sought in all cases of burn injury:

• Time of the burn

• Burning agent

• Is the patient complaining of pain?

• Has the patient jumped or been involved in an explosion?

• Was the patient in a confined space?

• Has the patient lost consciousness at any time?

• A brief medical history, drug and allergy history (AMPLE)

• Tetanus status of the patient.

Simple erythema

Simple erythema is a superficial burn with no skin loss, e.g. sunburn. The skin is red and tender; this heals in 5–10 days with no scarring.

Superficial partial-thickness burn

Blisters are thin-walled and the burn is extremely painful. The skin is red and moist with a granular appearance and the germinal layer is not penetrated; an example is a scald from boiling water. Healing takes 10–20 days and there is minimal scarring.

Deep partial-thickness burn

A deep partial-thickness burn can be produced, e.g. by boiling fat; it is deeper than the superficial partial-thickness burn and the blisters are thick-walled. The underlying skin is granular and white in appearance, with pinpoint red mottling; sensation may be dulled. Healing is by migration of epithelial cells from the edge of the wound or skin adnexa, which takes 25–60 days.

Deep full-thickness burn

Full-thickness burns are caused by prolonged contact with the burning agent or dry heat. The appearance is white, leathery or charred. Although the areas of full-thickness burn are painless, the depth of the burn is usually shallower around its margins and these areas will be painful. This burn affects the full thickness of the skin and may extend further into fat, muscle or bone; it does not heal. Treatment includes tangential excision and either skin graft or free flap repair, depending on the depth.

Types of burn

• Wet heat

• Dry heat

• Flash burns

• Chemical burns

• Electrical burns

• Radiation burns.

Extent of burn

It is important to assess the extent of the burn accurately. Methods include:

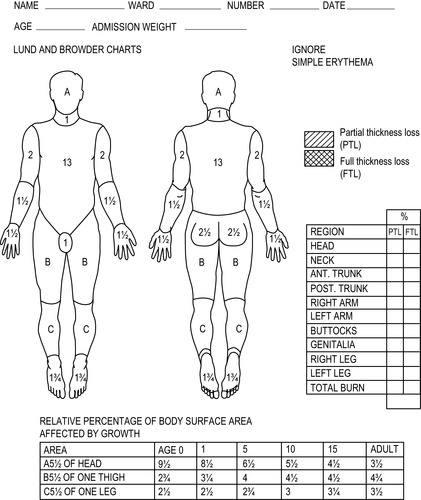

• The Lund and Browder chart (Figure 31.1) – this is more appropriate for in hospital use

|

| Figure 31.1 |

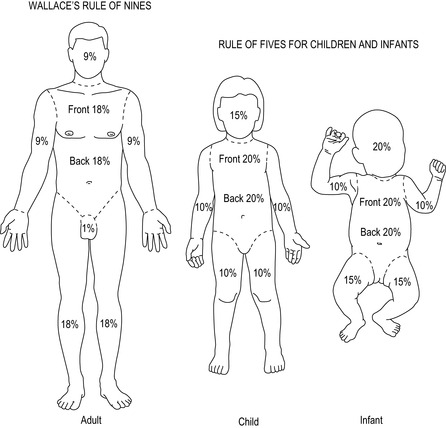

• The rule of nines for adults (Figure 31.2)

• The rule of fives for children and infants (Figure 31.2)

• Using the approximation that the patient’s hand (flat with the fingers together) is equal to 1% of the patient’s body surface area

• Serial halving. Ask ‘Does the patient have 100% burns?’ If not, ‘Does the patient have 50% burns?’ and so on until an estimation is reached that reflects total body surface area burnt (excluding erythema).

As the time of exposure to the burning agent is increased, the severity of the burn increases

Burn site

Burn sites with a poor prognosis are:

• Face

• Hands and feet

• Eyes

• Ears

• Perineum.

Facial burns are often associated with an inhalation injury

Circumferential burns

If there is a circumferential burn to the neck this can cause airway obstruction. Circumferential burns to the limbs produce constriction, causing oedema and distal ischaemia. A circumferential burn to the chest can lead to respiratory failure.

Inhalation injury

Inhalation injury is now the major cause of death in burns and occurs in 15% of burn patients who are admitted to hospital.

There are three different pathological processes:

1. Direct thermal injury from hot gases

2. Inhalation of smoke containing harmful chemicals

3. Systemic poisoning from carbon monoxide or cyanide.

The upper airway is damaged by either direct thermal injury or smoke inhalation. This leads to oedema and sometimes obstruction of the upper airway which can have a rapid onset.

The lower airway is damaged by smoke; in addition, superheated steam can produce thermal damage to the alveoli and this has a poor prognosis.

Smoke inhalation can cause sloughing of the airway lining, producing obstruction and inflammation followed by pulmonary oedema and hypoxia.

Inhalation injury should be rapidly assessed and treated promptly.

Mortality will be higher in patients with an underlying respiratory illness.

If there is any evidence of an inhalation injury or a critical burn, the patient should be given the highest concentration of oxygen available

Features suggestive of inhalation injury

• History of being confined with the fire in a closed space

• History of unconsciousness at the time of the incident

• Exposure to smoke or gas during the incident

• Evidence of burns to the face

• Singed nasal hair

• Cough or carbonaceous sputum

• Blistering or redness in the mouth

• Evidence of laryngeal oedema, e.g. hoarseness, stridor

• Wheezing

• Signs of airway obstruction or respiratory distress

• Full-thickness burns to the nasolabial area of the face or posterior pharyngeal swelling.

Critical burns

Critical burns will normally require specialist management in a burns centre.

Critical burns

• Simple erythema over more than 75% of the body surface area

• Partial-thickness burn exceeding 10% surface area in a child, 15% in an adult and 5% in an elderly patient

• Deep burn over more than 10% of the body surface area

• Inhalation injury

• Burns complicated by a fracture or major soft tissue injury

• Burns in patients with associated medical conditions

• Any chemical or electrical burns.

Safety at the scene

Ensure that the environment is safe. It may be necessary to wait for the fire service to put the fire out or to rescue the burned patient. Simply opening a door or window enhances the oxygen supply to the fire, increasing its intensity or possibly causing a flash-over.

Stopping the burn process

Dry and wet heat

• If the patient’s clothes are on fire, force them to the floor and wrap them in a blanket to extinguish the flames

• If the clothes are smouldering or have hot liquid on them, they must be removed quickly

• If the clothing is stuck or burnt onto the skin the clothes must be cut around the adhesive area and soaked with clean cold water to minimise the burn process

• Burns that are extensive from either dry or wet heat (e.g. flame or scald) can be soaked with clean cold water but cold water must not be left on the burn for more than 10 minutes unless it is less than 5% of body surface area

• It is vital to ensure that patients with burns do not become hypothermic.

Cool the burn; warm the patient

Tar burns

The tar should not be removed but immersed in cold water to cool the area and to stop the burning process.

Chemical burns

• All clothing should be removed from the affected area and any dry powdered chemical brushed off

• The burn should be copiously washed with large quantities of water for up to 10 minutes at the scene. The patient may then be transferred to hospital

• The severity of chemical burns depends upon the agent, the time of contact and the concentration

• Some alkaline substances, such as wet cement, are highly corrosive and will continue to burn until completely removed

• Acid burns usually produce less damage but will continue to burn if left on the skin. An exception to this is hydrofluoric acid which penetrates deeply and produces extensive tissue destruction and pain; these burns require treatment with calcium gluconate applied topically.

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Presentation

If large amounts of carbon monoxide are present, oxygen is displaced from haemoglobin and large quantities of carboxyhaemoglobin are produced.

The binding of carbon monoxide to haemoglobin is much stronger than that of oxygen which reduces oxygen transport and worsens tissue hypoxia.

The half-life of carboxyhaemoglobin in room air is 320 minutes; on 100% oxygen it is 80 minutes and on 100% oxygen at 3 atmospheres (hyperbaric oxygen) it is 23 minutes.

The signs and symptoms of mild carbon monoxide poisoning are:

• Lethargy

• Muscle weakness

• Headache

• Nausea

• Vomiting.

The signs and symptoms of severe carbon monoxide poisoning are:

• Cyanosis

• Coma

• Pulmonary oedema

• Dilated pupils.

Management

Any person with carbon monoxide poisoning should be given 100% oxygen and transferred to the accident and emergency department immediately.

Pulse oximetry will not detect the difference between carboxyhaemoglobin and oxyhaemoglobin and may therefore appear falsely reassuring.

After arrival at hospital, the patient is considered for hyperbaric oxygen if:

• The patient is unconscious at any time

• The carboxyhaemoglobin concentration exceeds 20%

• Neurological signs and symptoms are present

• The patient is pregnant.

Patients with carboxyhaemoglobin levels of 50–60% are comatose and require ventilatory support.

Fluid resuscitation

• Intravenous fluids must be started in a patient with a burn greater than 25% of body surface area or if the transfer time is greater than one hour, as vast quantities of plasma will be lost from the burn

• Look for other injuries as a cause of hypovolaemic shock

• Avoid obtaining intravenous access through burnt skin

• Give 1–2 litres of crystalloid in adults or 10 mL/kg in children.

Analgesia

Partial-thickness burns are extremely painful and either Entonox can be self-administered by the patient or the patient can be given intravenous morphine.

No analgesic drug should be given intramuscularly or subcutaneously in severe or moderate burns, as it will remain unabsorbed owing to poor circulation.

Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs are contraindicated due to the risk of gastrointestinal problems or ulcer formation.

It is essential that hospital medical staff are made aware that opiate analgesia has been given

Dressings

The burned area should be wrapped in clingfilm or sterile towels to reduce pain.

If the burn is less than 5% of body surface area, sterile cold water or saline soaks are placed on top of the clingfilm to reduce contact with the air, reduce pain and cool the burn.

If clingfilm is unavailable, clean sterile towels can be placed on the burn prior to rapid transfer to hospital.

Circumferential clingfilm should never be applied to the thorax or limbs. Individual sheets of cling film should be gently laid on the burned area.

Under no circumstances should any cream (antibiotic or otherwise) be applied to a burn before hospital assessment

Disposal

All burn patients should be transferred to hospital and there a decision can be taken as to whether the patient needs to be transferred to a burns unit, admitted to the hospital from the accident and emergency department or treated as an outpatient. Critical burns should be sent, wherever possible, to a hospital with a burns unit as long as general resuscitative and treatment facilities are available.

For further information, see Ch. 31 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.