3.5 Burns

Pathophysiology

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and its functions include:

The skin is composed of two main layers.

Epidermis: composed of stratified squamous epithelium, which is largely non-viable. It acts as the barrier to infectious agents as well as preventing fluid loss from the body.

Epidermis: composed of stratified squamous epithelium, which is largely non-viable. It acts as the barrier to infectious agents as well as preventing fluid loss from the body.History

Non-accidental injury should be considered if the presentation is delayed or where the history given is inconsistent with the burn sustained or if the burn has distinctive distribution (e.g. glove and stocking). Past medical history and immunisation status, particularly for tetanus, should also be obtained (see Chapter 1.1).

Examination

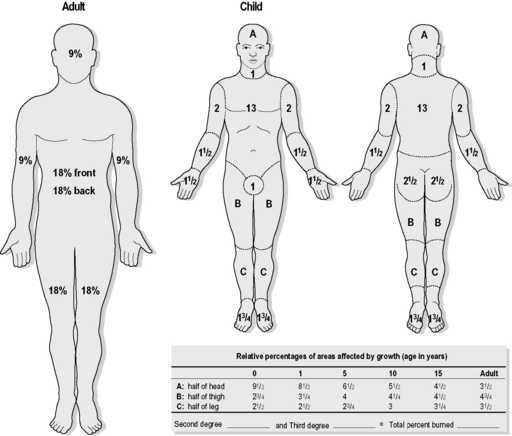

Evaluation of burn area

The extent and depth of the burn should be assessed after the patient has been stabilised. This is usually done from a body chart (Fig. 3.5.1), which can be useful to aid documentation of the burn. This chart is used because the surface area involved will alter depending on the age of the child and the parts of the body where the burn is located. A simple method, using the palmar surface of the child’s hand and fingers, can also be used to estimate the area of burn. This correlates to approximately 1% of the child’s total surface area. The adult formula using the ‘rule of nines’ can be used in adolescents older than 15 years.

Management

Emergency department

Other potential indications for ventilation in major burns include:

Management of burns (Table 3.5.1)

Superficial burns

Electrical burns

Clinical effects

Cardiac

Klein G.L., Herndon D.N. Burns. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25(12):411-416.

Holland A.J.A. Pediatric burns: the forgotten trauma of childhood. J Can Chir. 2006;49(4):272-277.

Sheridan R. Outpatient burn care in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(7):449-456.

Hight D.W., Bakalar H.R., Lloyd J.R. Inflicted bums in children: Recognition and treatment. JAMA. 1979;242:517-520.

Dunn K., Edwards-Jones V. The role of Acticoat™ with nanocrystalline silver in the management of burns. Burns. 2004;30(suppl 1):S1-S9.

Smith M.L. Pediatric burns: Management of thermal, electrical, and chemical burns and burn-like dermatologic conditions. Pediatr Ann. 2000;29(6):367-383.

Patel P.P., Vasquez S.A., Granick M.S., Rhee S.T. Topical antimicrobials in pediatric burn wound management. J Craniofacial Surg. 2008;19(4):913-921.

Walker A.R. Emergency department management of house fire burns and carbon monoxide poisoning in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996;8:239-242.