7 Burns

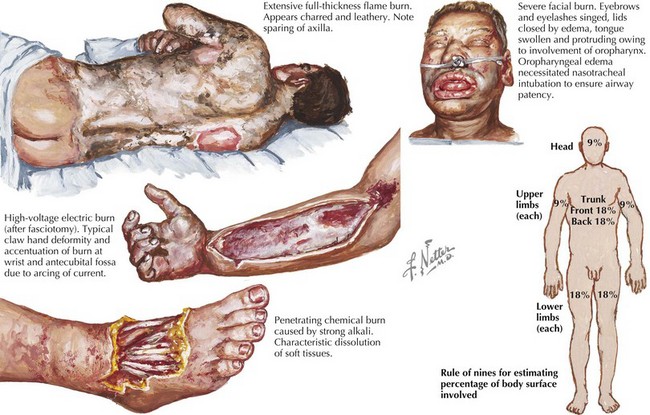

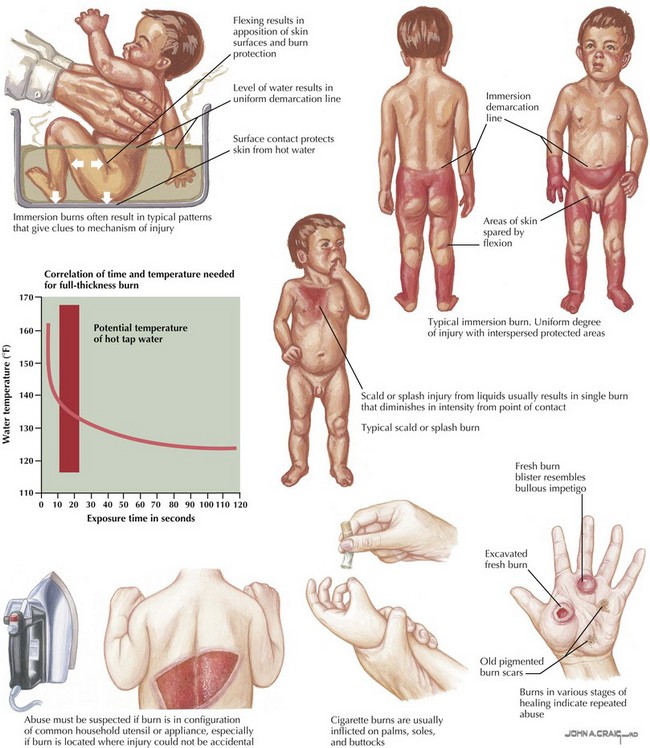

Burns and fire-related injuries account for significant morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population. In children younger than 18 years of age, fires and burns are the third leading cause of death from unintentional injury in the United States. Approximately one-third of all burns occur in children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age. Boys and children younger than 5 years of age are at highest risk of burn injuries. Burns may be thermal (resulting from flame, scald, steam, or contact), electrical, or chemical in cause (Figure 7-1). In children younger than 5 years of age, scalds resulting from bathing injuries or hot liquid spills account for the majority of burns. Fire and flames are the leading causes of burns in children older than 5 years of age. Electrical burns are seen primarily in adolescents. Child abuse accounts for up to 20% of burns in children and thus needs to be considered in all cases of pediatric burns, particularly in those with inconsistent mechanisms or specific patterns of injury (see Chapter 12). Carbon monoxide poisoning can occur with smoke inhalation and is responsible for many early deaths related to fire.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

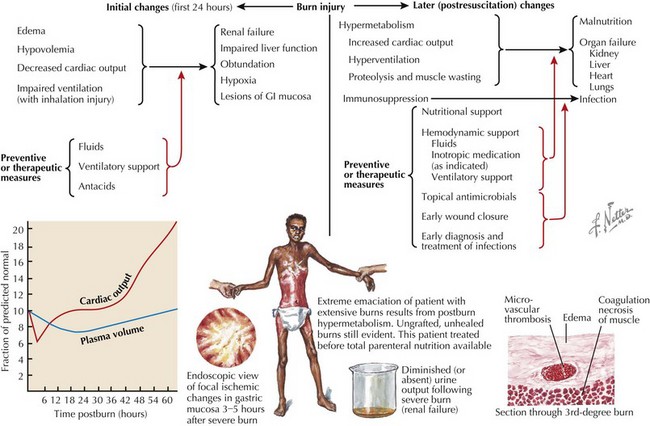

Larger burns may produce systemic effects (Figure 7-2). Bacterial colonization of burned tissue may result in infection caused by disruption of the protective epidermal barrier and the inability of immune system elements and antibiotic agents to penetrate burned tissue. Capillary permeability is increased by the release of osmotically active substances into the interstitial space and the release of vasoactive mediators into the systemic circulation. Edema with resulting intravascular hypovolemia results in both injured and noninjured tissues. Circulating factors reduce myocardial function, thus decreasing cardiac output. Direct heat damage and a microangiopathic hemolytic process result in acute hemolysis of erythrocytes. All of these acute processes may result in renal failure, liver dysfunction, mental status changes, and hypoxia. After the initial injury, a hypermetabolic and immunosuppressive state may ensue, resulting in malnutrition, infection, and multisystem organ failure.

Clinical Presentation

The diagnosis of a burn injury is typically evident from the patient’s history and clinical presentation. The differential diagnosis includes erythroderma, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; however, these are quickly distinguished from burns based on history and presentation. Certain patterns of injury are classic for an intentional burn as a result of child abuse (Figure 7-3). Scald injuries of the buttocks and thighs accompanied by perineal or foot injury that spares the flexion creases is classic for intentional injury with defensive posturing. Symmetric burns of the hands or feet with clear lines of immersion are classic for forced submersion injuries. Small, round, deep burns are suggestive of intentional cigarette burns. Any deep wound with some geometric pattern may suggest a contact burn, such as an iron. Suspicion should be raised for abuse in any case with a nonspecific history, a mechanism that is inconsistent with the clinical presentation, delayed presentation, or a classic injury pattern.

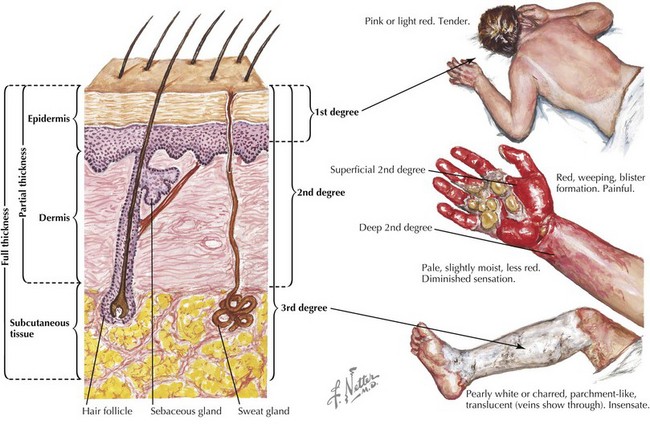

Burns are traditionally classified by the depth of skin injury (Figure 7-4). Superficial burns, formerly known as first-degree burns, involve the epidermis only and present with pain and redness over the affected areas without significant edema or blistering. These burns resolve in 3 to 5 days without residual scarring. Of note, superficial burns are not included in burn surface area (BSA) calculations.

To adequately determine the extent of burn injury, the surface area and burn depth must be assessed. This is essential for guiding therapy, disposition, and prognosis. In adults and children older than age 15 years, the “rule of nines” is used to assess BSA—9% for the head and neck and each upper extremity and 18% for the trunk, back, and each lower extremity (Figure 7-1). The rule of nines cannot be used for children younger than age 15 years because of their proportionally larger head and different body proportions. Specialized charts that estimate burn area based on age can be used to estimate BSA for younger children. A rough estimate may be provided using the child’s palm, which represents approximately 1% of BSA.

Evaluation and Management

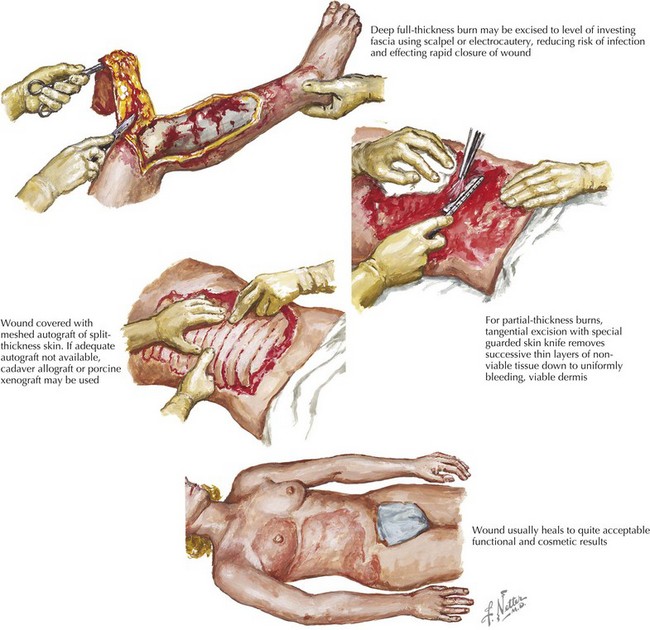

The burn wounds should be covered loosely with clean sheets until they are ready to be assessed and treated to protect the wounds and minimize pain. The wounds should be cleaned with large volumes of sterile warm saline, and loose tissue should be debrided gently with sterile gauze. Temporary skin substitutes, such as Biobrane, may help to reduce pain, facilitate healing, and decrease the length of hospitalization. These dressings consist of a silicone outer layer that acts as a protective epidermal barrier and an inner surface consisting of collagen peptides that bind to wound surface fibrin and facilitate reepithelialization. Topical antibiotics, such as silver sulfadiazine, bacitracin, or mafenide acetate, should be used for larger and more contaminated burns. Escharotomy should be considered in all full-thickness burns that have the potential to threaten circulation to an extremity. Surgical excision and skin grafting should be considered in deep partial-thickness and full-thickness burns (Figure 7-5). Pain control should be attended to promptly in patients with partial-thickness burns, with morphine being the drug of choice for severe burns and acetaminophen or ibuprofen for use with minor burns.

Appropriate disposition of these patients is essential to optimize treatment outcome. Specialized burn centers have been developed that have the resources to provide aggressive medical, psychological, and rehabilitative care to children with significant burns. The American Burn Association has developed criteria for referral of patients to burn centers (Box 7-1). Appropriate and timely treatment and disposition can potentially improve the outcomes and quality of life of children with burn injuries.

Box 7-1

American Burn Association Criteria for Referral to a Burn Center

Excerpted from Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons: Guidelines for the Operation of Burn Centers, Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient, 2006, pp 79-86.

American Burn Association. Available at http://www.ameriburn.org

Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, et al. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):403-434.

Holland AJA. Pediatric burns: the forgotten trauma of childhood. Can J Surg. 2006;49(4):272-277.

Patel PP, Vasquez SA, Granick MS, Rhee ST. Topical antimicrobials in pediatric burn wound management. J Craniofacial Surg. 2008;19(4):913-922.

Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG. Topical treatment of pediatric patients with burns: a practical guide. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(8):529-534.

Schulman CI, Ivascu FA. Nutritional and metabolic consequences in the pediatric burn patient. J Craniofacial Surg. 2008;19(4):891-894.

Whitaker IS, Cantab MA, Prowse S, Potokar TS. A critical evaluation of the use of Biobrane as a biologic skin substitute. Ann Plastic Surg. 2008;60(3):333-337.