Bunionectomies

Joshua Gerbert and Neil McKenna

Definitions

The term “bunion” refers to the any enlargement around the first metatarsal phalangeal joint (MTPJ). The term “hallux valgus” has been used as a catch-all phrase to include all types of bunions without being specific. The actual definition of “hallux valgus” is a frontal plane deformity of the great toe in which the plantar aspect of the toe is beginning to face the second toe. “Hallux abductus” is a transverse plane deformity of the great toe in which it is moving toward, abutting, overriding, or underriding the second toe. In most cases the surgeon will make a diagnosis of “hallux abductus with bunion deformity” (Fig. 32-1) or “hallux abducto-valgus with bunion deformity” depending upon the preoperative position of the great toe. A “dorsal bunion” is an enlargement over the dorsal aspect of the first MTPJ and in most situations is indicative of limited first MTPJ motion known as “hallux limitus.”

Etiologies

Bunion deformities are complex problems and dynamic, meaning that over time the deformity will most likely progress regardless of the conservative measures employed. This is especially true if there is any structural malalignment of the bones that comprise the first ray. Once a “bunion” deformity has developed there are no conservative measures that will reverse the situation. Conservative measures may halt the progression of the deformity and/or reduce the symptoms associated with it. The etiologies are varied and at times are the result of several different causes. The following are the more common causes of bunion deformities:

It should be noted that once the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the LE abnormally function during gait and the patient significantly pronates, the hallux begins to deviate toward the second toe and retrograde forces on the first metatarsal begin to move this bone more medially. The more transverse plane mobility that exists at the first metatarsal cuneiform joint (MCJ), the more the first metatarsal may splay from the second metatarsal. The more sagittal plane mobility that exists at the first MCJ, the more the first metatarsal will migrate dorsally and produce limited first MTPJ motion (hallux limitus rather than a medial bunion deformity with a hallux abductus).

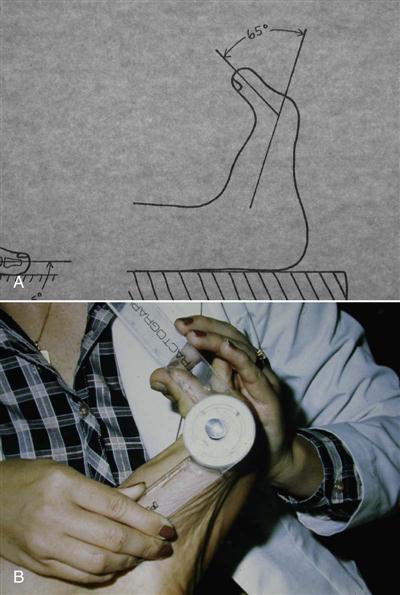

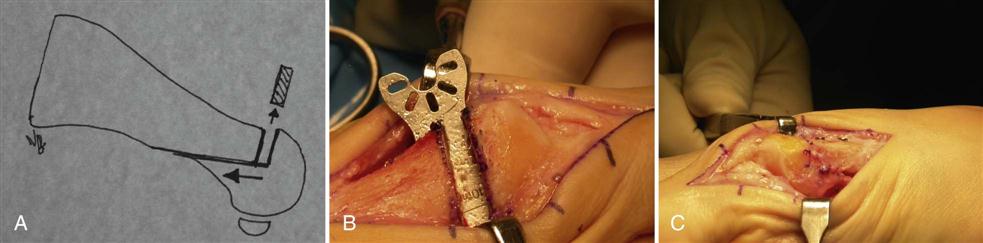

Indications and Considerations for Surgical Correction

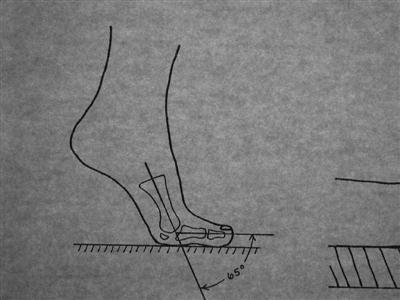

A very detailed clinical examination of the foot and LE is required both non–weight bearing and weight bearing to determine areas of pathology contributing to the “bunion” deformity. Objective measurements of the first MTPJ range of motion (ROM) (dorsiflexion and plantarflexion) are obtained non–weight bearing (Fig. 32-2). The amount of dorsiflexion deemed necessary for a normal propulsive gait is approximately 65° (Fig. 32-3). Since plantarflexion of the first MTPJ is not a motion required for gait, there are really no normal values usually considered other than knowing that the first MTPJ can plantarflex to some degree without discomfort. Evaluation of mobility at the first MCJ on both the transverse and sagittal planes is important to detect any hypermobility. If sagittal plane hypermobility of the first ray appears to exist, then one should dorsiflex the hallux at the first MTPJ and evaluate the motion again. By dorsiflexing the hallux, one is engaging the plantar fascia (windlass mechanism). If the abnormal sagittal plane motion is no longer present, then the use of an orthotic device will most likely halt any deforming forces caused by hypermobility of the first ray, which are usually jamming of the first MTPJ in gait, limited first MTPJ motion, and transfer metatarsalgia. However, if by engaging the windlass mechanism by dorsiflexing the hallux and the hypermobility appears to remain, then a surgical procedure aimed at stopping this motion is usually needed, such as a fusion of the first MCJ known as a Lapidus procedure. Symptoms may not always be the indication for pursuing a surgical correction of the “bunion.” A patient who has a progressive hallux abductus and a bunion deformity in which the hallux is significantly abutting the second toe but is asymptomatic may require a surgical correction of the deformity to prevent deformity of the second toe and dislocation of the second MTPJ.

Weight-bearing radiographic evaluation of the foot is extremely important in the evaluation of the “bunion” deformity to determine any structural malalignment of the first ray and at which level or levels the pathology exists (Fig. 32-4). A unique aspect of the first MTPJ is the presence of two sesamoid bones on the plantar aspect of the metatarsal head (Fig. 32-5), which serve as a fulcrum for the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis muscle that attaches to the plantar aspect of the base of the proximal phalanx. At times the fibular sesamoid bone may become a very powerful deforming force and the surgeon may need to release its soft tissue attachments or excise it (Fig. 32-6). This maneuver can create scar formation to such an extent as to limit first MTPJ dorsiflexion postoperatively.

Various angular measurements are taken and correlated with the clinical examination.

The surgeon must also take into consideration the patient’s overall medical health, body type, age, occupation, and home environment before deciding which surgical procedure or procedures would best correct that patient’s “bunion” deformity. While the clinical and radiographic evaluation data may indicate an “ideal” surgical correction, the specific medical and/or social data on that specific patient may dictate a lesser surgical correction.

Surgical Procedures

Since there are a wide variety of surgical procedures used to correct a “bunion” deformity, and in many cases the surgeon may perform more than one procedure to correct the deformity, I thought it would be beneficial to the physical therapist to put the procedures in categories as they relate to postoperative management and to briefly describe the major aspect of the procedure. This chapter does not allow me to cover every type of procedure used to correct “bunion” deformities. However, the following are the more common ones.

Category 1

Category 1 procedures are those in which the patient can begin immediate propulsive ambulation following surgery and return to high impact activities within 2 to 3 weeks.

1 Soft tissue rebalancing of the first MTPJ—McBride type (rarely performed as an isolated procedure) (Fig. 32-7)

2 First MTPJ prosthesis—total or hemi (Fig. 32-8)

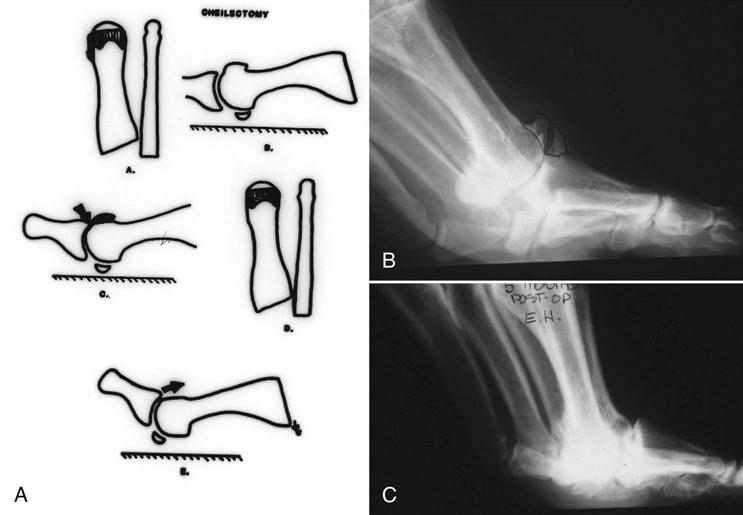

3 Cheilectomy—removal of bone spurs from the dorsal aspect of the first MTPJ in hallux limitus (dorsal bunion deformity) (Fig. 32-9)

4 Resectional arthroplasty of the first MTPJ—Keller type (usually performed in a very elderly patient with a nonsalvageable first MTPJ) (Fig. 32-10)

Category 2

Category 2 procedures are those in which the patient can bear weight immediately; however, the propulsive phase of gait must be eliminated for 2 to 3 weeks following surgery and the patient cannot resume high impact activities for 8 weeks.

Category 3

Category 3 procedures are those in which the patient can bear weight immediately; however, the propulsive phase of gait must be eliminated for 4 to 6 weeks following surgery and the patient cannot resume high impact activities for 12 weeks.

Category 4

Category 4 procedures are those in which the patient must remain non–weight bearing for 6 to 7 weeks following surgery and the patient cannot resume high impact activities for 12 to 16 weeks.

Category 5

Category 5 procedures are those in which a bone graft was used at the osteotomy site or fusion site and the patient must remain non–weight bearing until the bone graft has become incorporated, which depending upon the size of the graft may take 3 months.

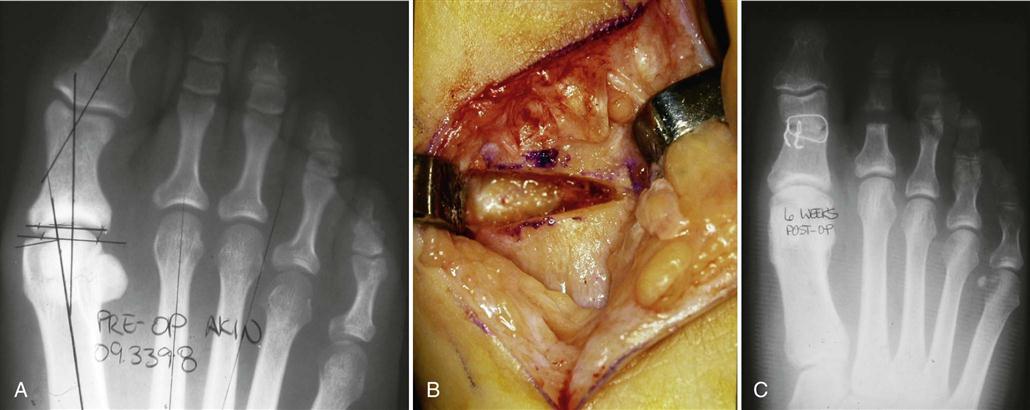

Underlying Pathology

In the majority of “bunion” deformities, the underlying pathology is a combination of both a soft tissue imbalance at the first MTPJ and a structural malalignment involving one or more of the bones comprising the first ray. Therefore the surgeon may need to perform combinations of procedures, such as an Akin osteotomy of the hallux, a McBride soft tissue rebalancing around the first MTPJ, and a metatarsal base osteotomy. The postoperative management would be dictated by the procedure that requires the most protection. So in the example given, the patient would need to remain non–weight bearing for 6 to 7 weeks because of the metatarsal base osteotomy. If the surgeon used rigid internal fixation and believed the patient to be compliant, then the patient may be allowed to begin early first MTPJ ROM and not be placed in a below the knee cast. This would of course allow for faster rehabilitation once the patient could resume weight bearing and return to normal activities.

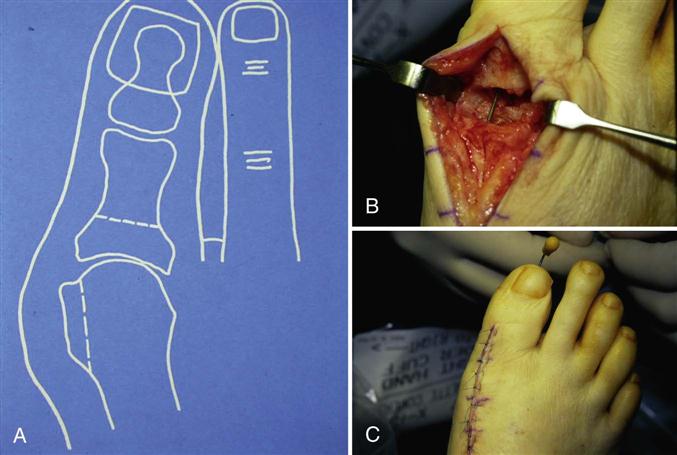

Surgical Procedure for A Metatarsal Head Osteotomy (Category 2) and Soft Tissue Rebalancing of the First MTPJ (Category 1)

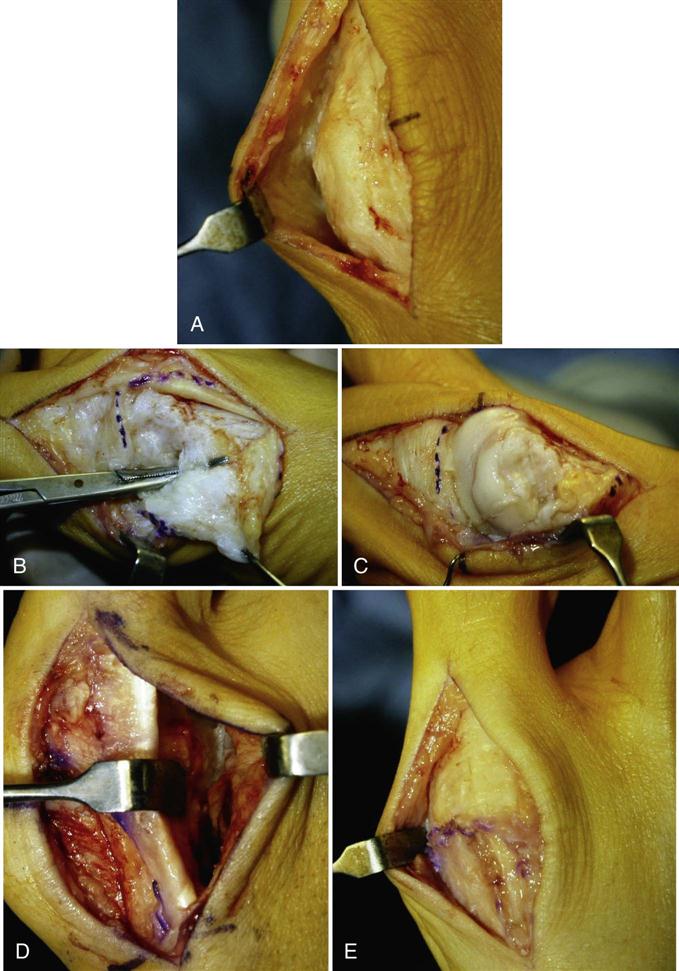

One of the more common bunionectomy procedures involves a first metatarsal osteotomy (Austin or Chevron procedure) and a soft tissue rebalancing (McBride procedure) to correct both a positional and a structural malalignment (see Fig. 32-11, A). A pneumatic ankle cuff is used to stop all blood flow into the foot and allow for a dry field during the procedure, which usually requires 45 to 60 minutes to complete. After a sterile preparation of the foot, a dorsal medial incision is made over the first MTPJ and by using blunt and sharp dissection the subcutaneous tissues and neurovascular elements are separated from the dorsal and medial aspect of the first MTPJ capsule (see Fig. 32-7, A). The surgeon then uses one of many capsulotomies to enter and expose the first MTPJ.

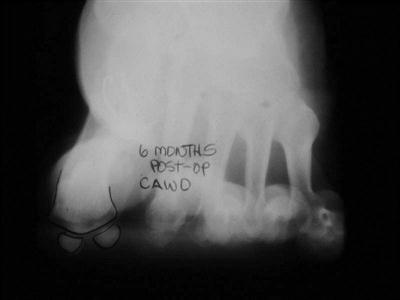

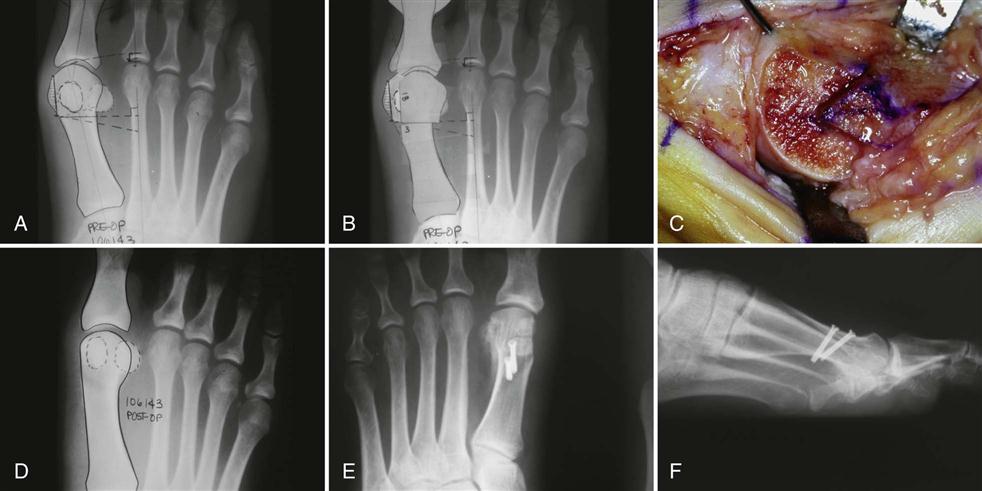

Fig. 32-7, B shows an inverted “L” capsulotomy having been performed and the incision through the medial suspensory and collateral ligaments. Following this maneuver, the surgeon then is able to expose the medial and dorsal aspects of the first metatarsal head as shown in Fig. 32-7, C. Based on the preoperative x-ray and a preoperative template, if constructed, the surgeon is able to determine how much of the medial eminence of the metatarsal head needs to be removed as seen in Fig. 32-11, B. Once the medial eminence has been removed, the surgeon can use a sterile marker and create the proposed osteotomy site. At this time and before performing the osteotomy, the surgeon decides whether to perform a lateral release of the first MTPJ or remove the fibular sesamoid bone; then further dissection is performed in the first interspace as shown in Fig. 32-7, D. Some surgeons elect to perform this maneuver through a second incision over the dorsal aspect of the first interspace. This portion of the procedure is performed to release any abnormally tight soft tissue structures that are holding the hallux in the abductus position. Using some type of power instrumentation, the bone is cut completely through from medial to lateral, severing all cortical surfaces as shown in Fig. 32-11, C. Then based upon the surgeon’s evaluation of the preoperative x-ray and/or preoperative template, the metatarsal head is transposed laterally toward the second metatarsal by a certain number of millimeters. Once the metatarsal head has been transposed to the desired amount, the osteotomy site is fixated based upon the surgeon’s preference and the medial overhang of bone on the metatarsal shaft is removed flush. Fig. 32-11, D is a postoperative radiograph in which the osteotomy site was fixated with absorbable rods, which are radiolucent. Fig. 32-11, E and F, are postoperative radiographs in which the osteotomy site for this type of procedure was fixated with two cannulated screws.

Once fixation is completed, the structural component now has been corrected. The next portion of the procedure is the completion of the soft tissue rebalancing. In this specific example an inverted “L” capsulotomy was performed medially. The surgeon’s assistant holds the hallux into a corrected position on the transverse plane, and the surgeon can then appreciate how much redundant medial capsular tissue is present. This medial redundant tissue is excised and the medial capsule closed using suture material of the surgeon’s preference (see Fig. 32-7, E). The dorsal portion of the capsule is then closed again using suture material of the surgeon’s preference. Some surgeons will elect to close the subcutaneous tissues and others will insert several buried knot sutures in the dermal layer to take the tension off the skin before skin closure. Skin closure is accomplished usually with a nonabsorbable material, again based on the surgeon’s preference.

Bandages are applied in such a manner as to control postoperative edema and reinforce the soft tissue realignment of the first MTPJ. The patient is placed either in a surgical postoperative shoe or a removable walking boot. Both devices allow for the patient to begin immediate ambulation with elimination of the propulsive phase of gait, which is needed because of the osteotomy procedure.

Potential Complications

For the physical therapist to better develop an effective rehabilitation program for a specific patient following a bunionectomy, the therapist needs to appreciate certain inherent anatomic changes associated with the procedures being performed. Furthermore, there are certain complications created intraoperatively by the surgeon that no amount of physical therapy will resolve. If possible the physical therapist should attempt to at least see a preoperative x-ray of the deformity because there are patients who have unrealistic cosmetic expectations of the end result.

The following are some of the more common complications associated with a bunionectomy procedure and possible causes:

1 Chronic edema at the surgical site

c Development of a hematoma, especially in the first interspace

d Prolonged cast immobilization

2 Delayed bone healing following a procedure involving an osteotomy

a Noncompliant patient who ambulated too soon following the procedure

b Poor internal fixation of the osteotomy site

c Medical factors (smoker, systemic steroid usage, osteoporosis, etc.)

d Traumatic event involving the surgical foot following surgery

a Overtightening of soft tissue structures around first MTPJ

b Dorsiflexion of the first metatarsal following an osteotomy of the metatarsal

e Failure of surgeon to create a congruous first MTPJ

f Soft tissue fibrosis and/or damage of the hallucal sesamoids at the plantar aspect of the first MTPJ

g Noncompliant patient who will not exercise first MTPJ or ambulate with a propulsive gait

h Weakness of the peroneus longus muscle or overpowering of the anterior tibial muscle

4 Lack of hallux toe purchase when the patient is standing

d Overtightening dorsally of soft tissue structures at first MTPJ

e Chronic edema at plantar aspect of the first MTPJ (metatarsal head osteotomy procedures)

5 Hallux separation from the lesser toes (Hallux varus)

a Overtightening of soft tissue structures at medial aspect of first MTPJ

Physical Therapy Considerations before Development of A Treatment Plan

The following are some facts that the physical therapist should attempt to know before establishing a treatment plan for a specific patient following a bunionectomy.

Expected Overall Outcome Following A Bunionectomy

For the majority of bunionectomies the following signs and/or symptoms to some extent may be present for 5 to 6 months postoperatively, even if the surgery was performed correctly and the patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

Preoperative Considerations

A biomechanical imbalance of the LE that results in excessive foot pronation is a common cause for bunion deformities. Physical therapists have a role in evaluating this inefficient motor plan. They can get the rehabilitative process started before surgery since this will ultimately need to be addressed. Plantar pressure of the medial foot during normal gait should be included in the preoperative evaluation if the therapist has the means to assess it. First metatarsal phalangeal (MTP) joint dorsiflexion and plantar flexion ROM measurements should be ascertained for baseline purposes. Strength testing of the LE musculature, in particular the peroneals and flexor hallicis longus/brevis, should be performed. Schuh and associates1 recommend using the metatarsophalangeal-interphalangeal score of the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society as a functional survey.

Initial Postoperative Examination

Patients should be both cognizant and compliant with their weight-bearing precautions, depending on the procedure(s) performed, to decrease their risk for complications. Therefore, it is imperative that the physical therapist is aware of the type of surgery that was performed and discusses it with the patient. It is also helpful to view the imaging studies to understand the full extent of the patient’s preoperative deformity. Refer to Box 32-1 for objective measures that should be included in the evaluation.

![]() Please remember that patients who have undergone procedures in categories 4 and 5 (metatarsal base osteotomies with or without a bone graft, fusion of the first MCJ, and fusion of the first MCJ or MTPJ with bone graft) require additional time for healing. Passive range of motion of these joints would be contraindicated if healing is not sufficient at this point. Therefore, it is imperative to consult with the surgeon regarding the integrity of the region before applying any therapist- or patient-generated forces across these joints.

Please remember that patients who have undergone procedures in categories 4 and 5 (metatarsal base osteotomies with or without a bone graft, fusion of the first MCJ, and fusion of the first MCJ or MTPJ with bone graft) require additional time for healing. Passive range of motion of these joints would be contraindicated if healing is not sufficient at this point. Therefore, it is imperative to consult with the surgeon regarding the integrity of the region before applying any therapist- or patient-generated forces across these joints.

Therapy Guidelines

There are no specific time parameters associated with these phases because of the variations in the types of procedures used. Procedures that include a metatarsal base osteotomy require 6 to 7 weeks of non–weight bearing. In comparison, the SCARF procedure allows for immediate weight bearing; however, the propulsive phase of gait cannot begin until the third to fourth week postoperatively.

The use of a bone graft in category 5 of the surgical procedures will preclude a patient from beginning therapy until the fusion site has adequately healed. The surgeon will ascertain this on subsequent postoperative follow-up visits. This may occur as early as 8 weeks, but can take up to 3 months. When this patient can begin physical therapy, you will place him or her in the appropriate treatment category depending on the weight-bearing status and specific postsurgical precautions.

Those patients that receive a procedure in category 4 (metatarsal base osteotomies and fusion of the first MCJ) may begin therapy earlier than those in category 5. The surgeon will refer the patient to physical therapy once the area is adequately healed; however, the patient may still be non–weight bearing.

In summary, selection of the appropriate rehabilitation phase depends on the patient’s weight-bearing status and associated stage of healing. Please refer to the tables for the guidelines related to each specific treatment category.

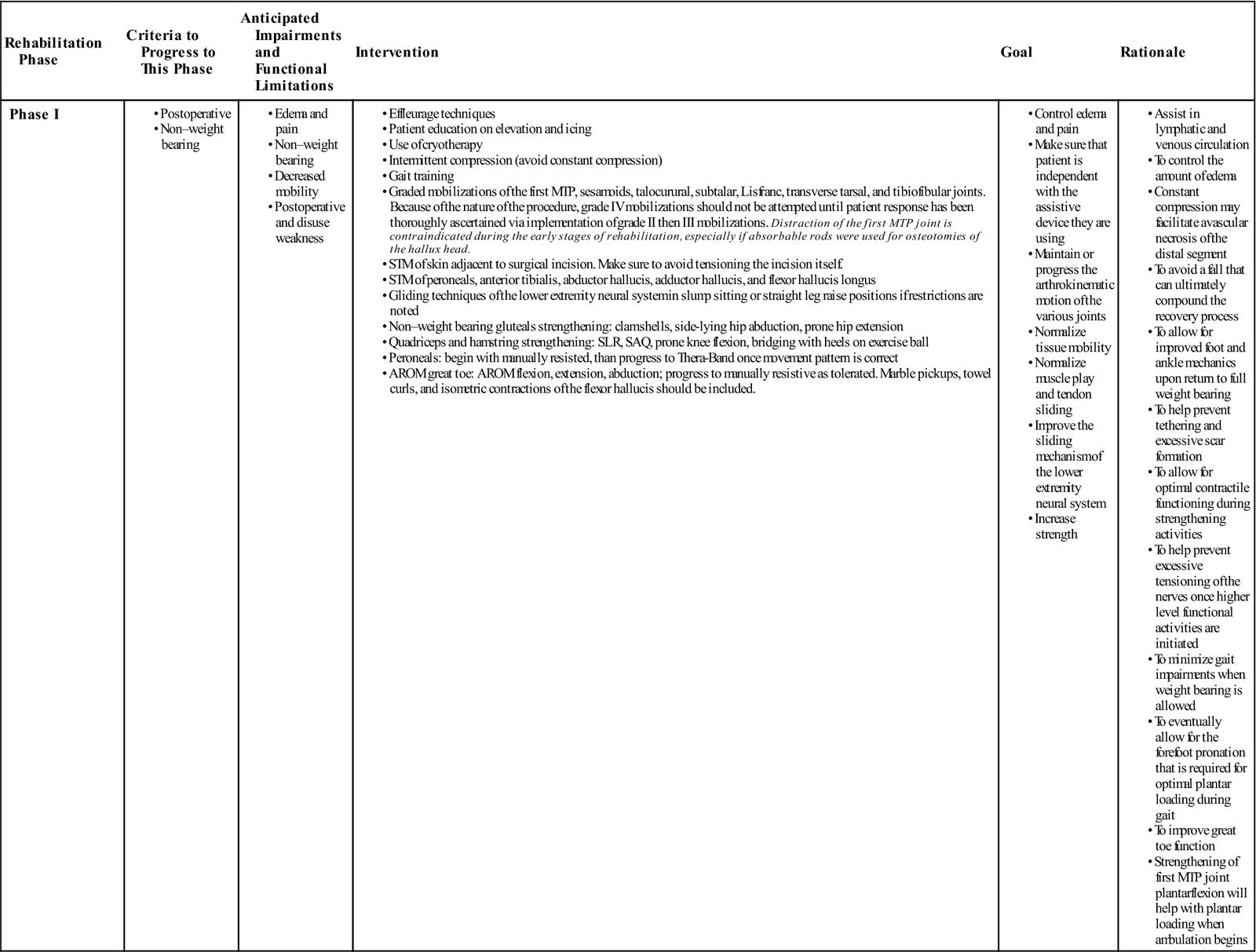

Phase I (Non–Weight Bearing) (Table 32-1)

It is common for the patient to demonstrate edema in the foot after a bunionectomy. It is imperative to control this via modalities, manual treatment, graded exercise, and patient compliancy with limited dependent positioning. Since the patient is non–weight bearing, he or she should be independent in the use of the assistive device. This will help avoid falls and compensatory pain patterns from occurring.

TABLE 32-1

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I |

|

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The ROM limitations that likely result from immobilization of the foot and ankle need to be addressed to avoid contractures that can lead to gait compensations and functional limitations. In the case in which the patient received a bone graft or fusion of a joint, it is imperative to protect the region as mobility is gained elsewhere. The physical therapist should consult with the surgeon before applying any manual forces across a surgically fixated joint. All of the structures that cross the ankle have the potential of demonstrating tightness; therefore the treatment needs to address myofascial and neural mobility as well.

The surgical site needs to be monitored for excessive scar formation and possible tethering because of the decrease in overall functional movement. If this area requires treatment, avoid tensioning the healing skin directly because this may adversely affect wound healing.

Disuse atrophy and weakness is another potential complication resulting from this non–weight bearing status. The physical therapist needs to take into consideration the prior functional level of the patient when creating this portion of the program. For example, if the patient is a tennis player, his program should include core and upper extremity strengthening exercises because of the relative disuse of these systems during this period.

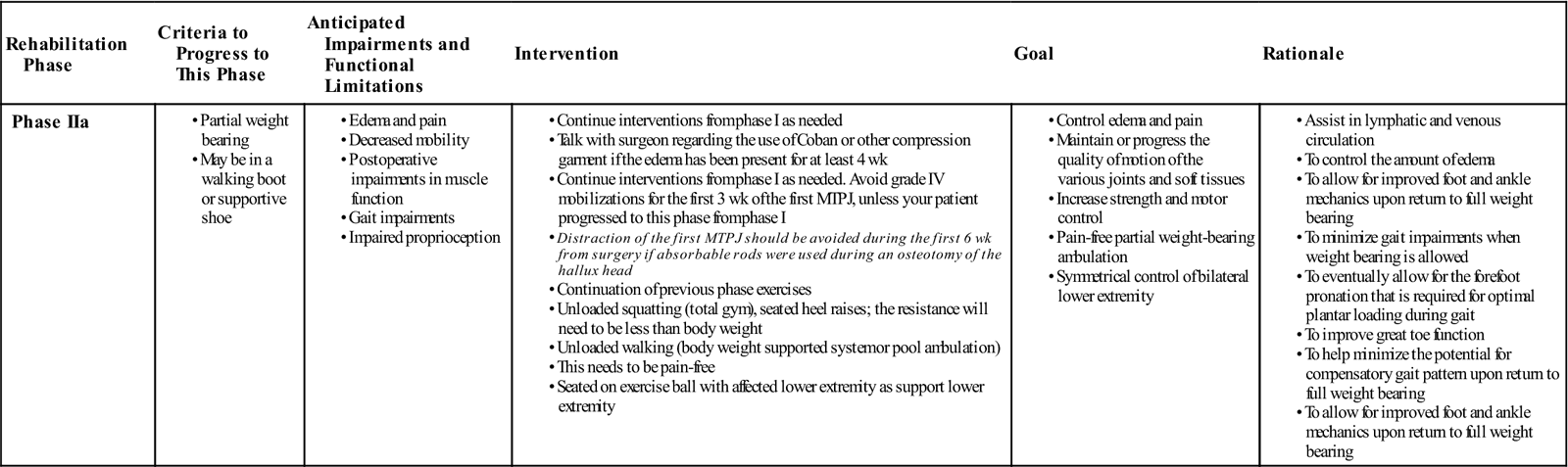

Phase IIa (Partial Weight Bearing) (Table 32-2)

The patient in this category will likely have a walking boot or supportive shoe. Edema control remains imperative at this stage. This is an opportune time to educate the patient on the relationship of swelling and initial weight bearing. It is not uncommon to experience increased swelling as the patient transitions into partial weight bearing. The patient should understand that a large increase in swelling that does not subside with rest may indicate periods of prolonged and/or excessive weight bearing. The patient will therefore need to modify her activity level to help minimize this inflammatory response. Mobility of the foot and ankle complex should be progressed as well. Remember to consider the various tissues that cross the ankle in addition to the arthrokinematics of the foot and ankle. Since the patient is beginning to ambulate, normal talocrural dorsiflexion should be achieved in this stage. Scar tissue monitoring and treatment of the surgical area needs to be included in this stage as well. Direct scar tissue massage on the affected skin should be avoided for the first 4 weeks postoperatively.

TABLE 32-2

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIa |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Strengthening of the LE and other functionally dependent regions should be initiated or maintained. Unloaded exercise is a valuable adjunct to this treatment as it helps to restore neuromuscular coordination associated with functional movement. Since the patient has begun to bear weight, proprioception of the LE becomes very important. Sitting on an exercise ball with unilateral leg support is an effective means for both assessment and treatment. He or she should demonstrate symmetry between both sides by the end of this phase.

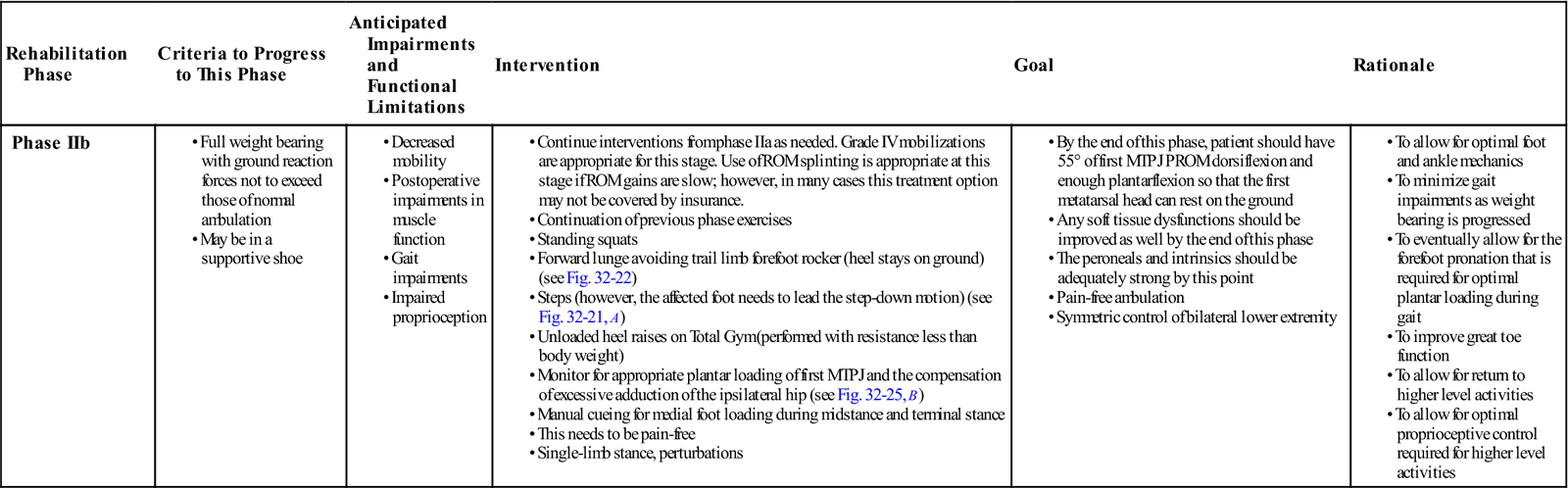

Phase IIb (Initial Full Weight Bearing) (Table 32-3)

The patient in this category may have a walking boot or supportive shoe. The patient will likely demonstrate increased swelling with the onset of full weight bearing. He or she needs to be educated on the direct relationship of excessive and/or prolonged loading and the inflammatory response. This will help to gradually return the patient to pain-free, full weight-bearing status.

Table 32-3

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIb |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

MTPJ, Metatarsal phalangeal joint; PROM, passive range of motion; ROM, range of motion.

The patient should have symmetric ankle dorsiflexion during this stage, and demonstrate at least 55° of first MTP joint dorsiflexion by the end of this stage. There should be enough first MTP joint plantarflexion so that the metatarsal head can rest normally on the ground. Regarding joint mobilizations, manual distraction of the first MTP joint should not occur until the sixth week postoperatively if absorbable rods were used. Symmetric soft tissue integrity of the foot/ankle complex and neural mobility should be accomplished as well. There should be no signs of scar tissue hypomobility by the end of this phase.

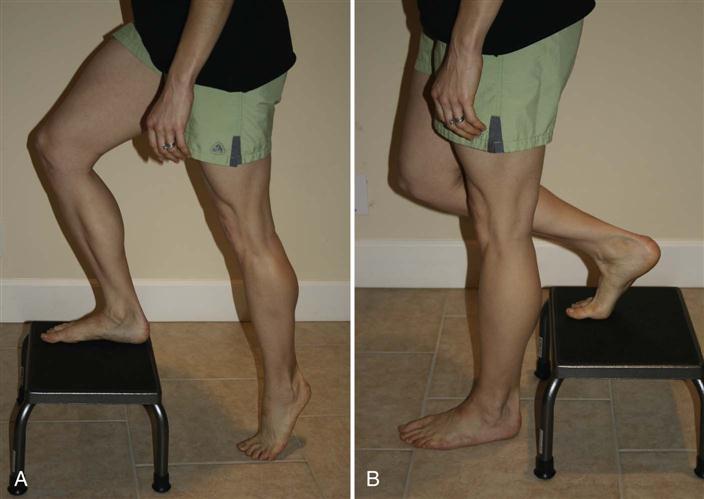

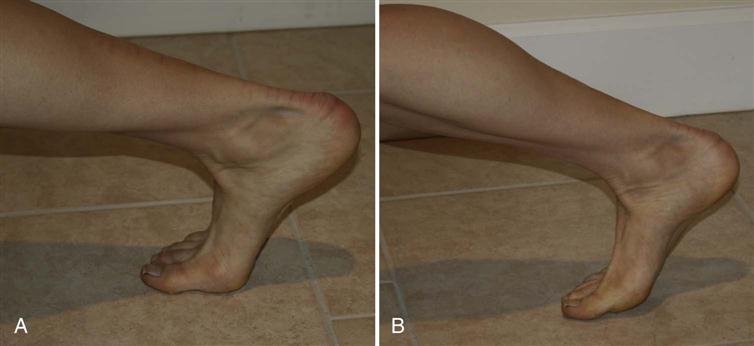

The strengthening program should be progressed to allow for functional weight-bearing exercises, such as squatting, stepping, heel raising, and lunging. Prescription of these exercises depends on the type of procedure. Category 2 procedures do not allow for forward propulsion during the first 2 to 3 weeks postoperatively. Therefore, this patient cannot step down with the nonsurgical foot first, as this will create the dorsiflexion at the affected first MTP joint that occurs during propulsion (Fig. 32-21). This is the same for category 3 patients; however, they need to avoid propulsion for the first 4 to 6 weeks. As a safety precaution, step-downs should begin from a step 7 inches or less in height. Forward lunges are appropriate; however, extension of the affected first MTP joint should again be avoided. This is accomplished by lunging forward in place and avoiding heel-off of the trail leg (Fig. 32-22).

As the patient performs these exercises, the physical therapist needs to monitor the quality and quantity of medial foot loading. Excessive medial loading needs to be immediately controlled. Limited medial loading may result from a combination of several factors: weakness or poor control of the peroneals and/or flexor hallucis brevis/longus, tightness of the medial foot (in the absence of an arthrodesis), limited subtalar joint eversion and/or talocrural joint dorsiflexion, restricted first metatarsal plantarflexion, or limited hip internal rotation. Pain and/or apprehension are another possibility. Once identified, the therapist should include treatment of the impairment(s) in the plan of care. Kernozek and associates2 demonstrated that although patients who received a distal metatarsal osteotomy 12 months prior had favorable outcomes (appropriate joint motion of both the ankle and first MTP joint and decreased pain with ambulation), they did not increase the loading of their medial foot compared with their presurgery data. These patients performed ROM exercises given by the surgeon and did not receive physical therapy. Shamus and associates3 found that increasing the ROM of the first MTP joint, improving the strength of the flexor hallucis, and gait training achieved a decrease in pain that was statistically significant from the control group in those diagnosed with hallux limitus. These studies illustrate the need for gait training and functional exercises that encourage appropriate LE mechanics, especially during this phase of the rehabilitative process.

Proprioception training should progress to standing activities. These should be tailored to the individual’s current impairment level and progressed in a fashion that best replicates the patient’s prior functional level.

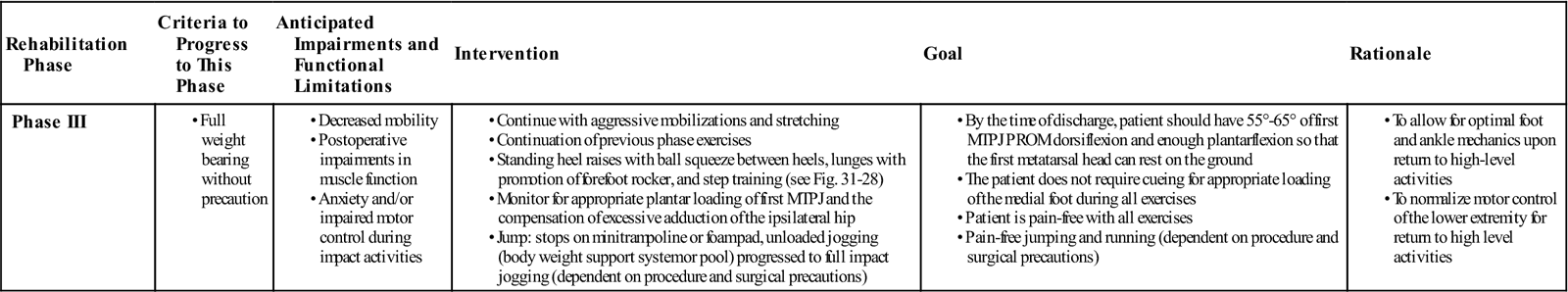

Phase III (Full Weight Bearing Without Precaution) (Table 32-4)

The patient in this category has no restrictions. They may have continued edema because of the progressed functional level. The patient should have symmetric bilateral ankle dorsiflexion, at least 55° to 65° of first MTP joint dorsiflexion, and the first metatarsal head should be resting on the ground naturally during stance.

TABLE 32-4

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

MTPJ, Metatarsal phalangeal joint; PROM, passive range of motion.

The main emphasis during this phase is to achieve the above stated goals and to begin with progressive loading beyond the normal gait pattern. This program should be highly individualized and based primarily on the prior functional level of the patient. The exercises should not produce pain, rather they should gradually progress pain-free loading.

By the end of this phase, the patient should have no gait deviations (especially limited medial foot loading). He or she should be able to perform a bilateral heel raise with full body weight with little to no pain. In terms of higher functioning patients, running and jumping will depend on the precautions associated with the type of procedure they received.

Troubleshooting

The physical therapist may encounter a patient who complains of hyperesthesia near the surgical region toward the onset of therapy. Desensitization techniques are extremely valuable at the onset of care to help manage complex regional pain dysfunctions. The patient should also be educated on the importance of self-desensitization techniques, as well as graded exposure to weight bearing and self-ROM methods to help reduce the patient’s anxiety over great toe function. This patient will require extra helpings of positive feedback regarding their progress throughout therapy.

Nerve entrapment of the superficial nerves surrounding the first MTP joint is another potential problem. As a precaution, activities that encourage toe flexion with concomitant ankle plantarflexion will help to mobilize this region. An example of this would be the use of marble pickups with the patient’s calcaneus hovering above the ground. Soft tissue techniques during the onset of therapy should help to mitigate this problem as well.

In the case that you suspect nerve compression (burning symptoms, cramping of the dorsal region, and/or unrelenting pain), confer with the surgeon regarding the use of iontophoresis.

Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient

The home maintenance section outlines the postoperation rehabilitation the patient is to follow. The physical therapist can use it in customizing a patient-specific program.

Clinical Case Review

1What information can the physical therapist give regarding postdischarge shoe fitting for the patient who received a bunionectomy?

Recommendations from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons4: have the feet measured regularly as this can change with aging; measure both feet and fit to the largest foot; perform the fitting at the end of the day when the feet are the largest; stand during the fitting; make sure there is  to

to  inch from the longest toe to the end of the shoe; the ball of the foot should fit well into the widest portion of the shoe; do not purchase shoes that feel tight in hopes of stretching them to fit; and there should be a minimum amount of heel slippage.

inch from the longest toe to the end of the shoe; the ball of the foot should fit well into the widest portion of the shoe; do not purchase shoes that feel tight in hopes of stretching them to fit; and there should be a minimum amount of heel slippage.

2Katrina comes to the physical therapy department for her initial evaluation. She brings her intake information and her prescription. The prescription states, “s/p bunionectomy, PT evaluation and treat.” Is this enough information for the therapist before he or she manually assesses the foot?

The physical therapist needs to know the type of procedure(s) that were performed for the bunionectomy. Each procedure has its own set of precautions in terms of weight-bearing status, when propulsion during gait can be initiated, and whether or not the therapist can apply manual forces across the joints of the medial forefoot.

3What other areas should be included in a physical therapy evaluation besides assessment of the local region following a bunionectomy?

Because of the functional significance of regional interdependence, the therapist should identify the quality and quantity of motion at the individual “links” of the kinetic chain. This should be conducted with the patient’s surgical precautions in mind. Of particular importance are the hip and ankle joints. To minimize the transverse stress on the first MTP joint, one needs to have appropriate hip extension and ankle dorsiflexion ROM. Weakness of the gluteus medius and/or posterior tibialis may also contribute to poor control of pronation, leading to an increase in stress. There are many other possibilities that may contribute to the hallux valgus deformity. Therefore, the physical therapist should have a thorough understanding of each patient’s functional movement and address what can be improved upon throughout the rehabilitative process.

4Keri received a cheilectomy and McBride soft tissue rebalancing 1 week ago and has come for her physical therapy initial evaluation. Why should the physical therapist assess the integrity of the first medial MTP joint soft tissue during this visit?

A portion of Keri’s medial MTP joint capsule may have been excised during this procedure. There may have been a surgical release of the lateral sesamoid as well. Therefore, it is imperative for the physical therapist to help prevent excessive scarring on the medial and medial-plantar aspects of this joint. This will help to minimize the likelihood of resultant limited hallux adduction, and possibly a hallux valgus deformity.

5What peripheral nerve may be affected in patients who receive a bunionectomy? How would it present if it were affected?

Because of the location of the incision either dorsomedially or medially, the dorsal digital branches of the superficial peroneal nerve may become entrapped if there is excessive scar formation. Paresthesia of the medial great toe, and possibly second and third toes, may be reported. A slump test and/or straight leg raise with superficial peroneal nerve bias would be helpful in identifying altered neurodynamics when compared with the uninvolved side.

6Simone underwent a SCARF procedure 3 weeks ago. During her treatment session, the therapist prescribes marble pickups and great toe flexion isometrics. Why?

Having the appropriate ROM and strength of first MTP joint flexion will facilitate medial foot loading. This motion is important for propulsion during activities such as running and jumping. Decreased medial foot loading may also place increased stress to the lateral foot, lateral knee, hip joint, and lumbar spine.

7Brian underwent a bunionectomy, is currently in stage 3, and has no weight-bearing precautions. He has been performing heel rises at home; however, he has begun to complain of ipsilateral fifth metatarsal pain. What should the physical therapist inspect in relation to this exercise?

Brian may be excessively loading the lateral aspect of his foot upon the heel rise motion. This could be due to many variables, including decreased strength of the flexor hallucis, limited first MTP joint dorsiflexion, pain, apprehension, peroneal weakness, and/or poor movement strategies. If the impairment were apprehension and/or poor movement strategy, placing a ball between both posterior tibias would help to facilitate the plantar loading of the medial foot. Otherwise, the physical therapist would need to treat the impairment and then reassess the response subsequently.

8Bernice received a fusion of the first MCJ with a bone graft 8 weeks ago. She has begun to bear weight, but reports a significant increase in swelling. Should the physical therapist be concerned? Why?

It is common to report an increase in swelling upon an increase in functional demand. However, the therapist needs to always consider the integrity of the graft, especially at transitional times of function. The duration and frequency of weight bearing needs to be gradually progressed within patient tolerance. The presence of ipsilateral pitting edema in the absence of vascular disease may indicate potential strain to the graft and should be communicated to the surgeon.

9When trying to increase dorsiflexion at the first MTP joint, how should the physical therapist mobilize the joint?

Since the head of the metatarsal is convex and the proximal end of the phalanx is concave, the proximal phalanx should be dorsally mobilized to improve dorsiflexion.

10Casey is currently full weight bearing without precaution following her bunionectomy 8 weeks ago. Casey demonstrates minimal loading of the medial aspect of her foot during the stance phase of gait when compared with the nonoperative side. Her ambulation is currently pain-free. The physical therapist has noted that her first MTP joint passive range of motion and active range of motion dorsiflexion and plantarflexion are within normal limits. The manual muscle testing of the flexor hallucis was a 5/5 bilaterally. What could this scenario indicate?

There are many possibilities that can explain this gait pattern. The therapist needs to ascertain if only one factor is responsible, or if there is an interaction of several impairments. Pain and/or apprehension are likely. If Casey demonstrates normal and pain-free squatting and stepping mechanics, then apprehension is the likely culprit. Restrictions in subtalar joint eversion, hip adduction, and hip internal rotation are likely explanations as well. In this case, the therapist would likely observe the same dysfunction upon squatting and stepping motions.