102

Bullous pemphigoid

Pemphigoid begins with a localized area of erythema or with pruritic urticarial plaques that gradually become more edematous and extensive.

The eruption is often symmetric and generalized. The plaques turn dark red or cyanotic in 1–3 weeks, resembling erythema multiforme, as vesicles and tense bullae rapidly appear on the surface.

Bullae rupture within 1 week, leaving an eroded base that does not spread and that heals rapidly.

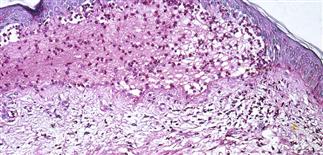

Skin biopsy shows subepidermal bullae with an infiltrate of eosinophils within the dermis and blister cavity.

DESCRIPTION

Uncommon, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease primarily affecting elderly.

HISTORY

• Most patients over 60. • No racial, gender prevalence. • IgG autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosomal proteins present. Trigger factor for formation of autoreactive antibodies unknown. Furosemide, captopril, some non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs implicated. • Untreated bullous pemphigoid may remain localized, undergo spontaneous remission, or may rapidly generalize. • Remission rate: 30% at 2 years, 50% at 3 years. Recurrences may be less severe than initial episode. • Mortality rate (1 year): 19%. Mortality risk from treatment side effects in addition to comorbidities.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

• Most often a generalized blistering eruption with predilection for intertriginous, dependent areas. Begins as itching and hive-like preblistering rash with localized area of erythema or with pruritic urticarial papules coalescing into plaques. Plaques turn deeper red in 1–3 weeks as vesicles and bullae rapidly appear on their surface. Bullae tense. Firm pressure on blister will not result in extension into normal skin, as occurs in pemphigus. Bullae rupture within 1 week, leaving eroded base that does not spread but heals rapidly. • Peripheral blood eosinophilia possible. • Skin biopsy with immunofluorescence recommended for all blistering diseases. Shows subepidermal bullae with an infiltrate of eosinophils and sometimes neutrophils within dermis and blister cavity. • Direct immunofluorescence of skin sampled next to a blister confirms IgG and/or complement C3 in a linear band at the basement membrane zone in about 90% of cases. • Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrates circulating autoantibodies in sera of approximately 70% of patients. Titers do not correlate well with disease activity, unlike in pemphigus.

TREATMENT

• Team approach with dermatologist, primary care provider, visiting nurse care if required. Goal of treatment is to arrest blistering, decrease itching, protect skin, limit secondary infection. • Prednisone probably treatment of choice (1.0–1.5 mg/kg q.d.) until blistering ceases. Most cases controlled in 28 days; can gradually taper dosage to 0.5 mg/kg q.d. (3 months), 0.2 mg/kg q.d. (6 months). • Forty percent of patients respond to dapsone (100 mg q.d.) alone. Addition of dapsone may help produce remission. • Consider adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy with cyclophosphamide or azathioprine if dapsone, prednisone fail. • May control limited disease with group I topical steroids. Apply twice daily until lesions healed, and 2 weeks thereafter. • Steroid-sparing agents include tetracycline 1.0–2.5 g q.d., minocycline 200 mg q.d., niacinamide 1.5–2.5 g q.d.. • Control itching with hydroxyzine 10–50 mg every 4 h as needed. Causes sedation. Use with caution in elderly. • Bedridden patients benefit from air mattress support, other skin-protective measures.