17 Building options into a core curriculum

Background

Information overload is one of the biggest problems facing students today.

In responding to the problem of information overload the teacher should:

• Recognise the need for students to move from simple fact memorisation to higher level learning objectives including searching, analysis and

synthesis of information. A theme running throughout the book is the changing role of the teacher from information provider to someone who opens the door for students and allows them to access and retrieve information for themselves.

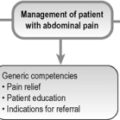

• Rather than teach more than students are able to learn and expect them to remember only a small proportion when they enter practice, it is preferable in the teaching to emphasise the core or essential learning required.

• Provide the opportunity for students to study in more depth areas of their choosing as either electives or student-selected components (SSCs).

Advantages of a core curriculum with options or student-selected components (SSCs)

A core curriculum offers a number of advantages:

• It is consistent with outcome-based education and highlights the essential learning requirements for all students.

• It helps to counter the tendency for increasing specialisation in the curriculum.

• It helps to determine the equivalence of training between different programmes and facilitates the mobility of doctors.

• It provides a standard against which students can be assessed.

When combined with options or student-selected components there are additional advantages:

• Students have the opportunity to cover the breadth of knowledge while at the same time they are able to study in depth selected subjects of their choosing.

• Special study modules may be offered in subjects not normally addressed in the curriculum.

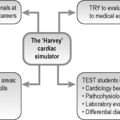

• Experience of a subject during an SSC may help students with regard to their career choice. Completion of a series of SSCs in a subject may count towards postgraduate training in that area, shortening the duration of postgraduate training. While unusual at present, this may be more widely recognised in the future.

• Teachers have the benefit of interacting with an enthusiastic group of students who have a special interest in their subject and who might be the researchers or teachers of the future.

Specification of a core curriculum

The specification of the core curriculum should be the responsibility of all the stakeholders including the clinicians and basic scientists. It should not be left to each discipline or specialty to specify the core curriculum in their area. The content can be determined as described in Chapter 7.

Choice of SSC topics

A wide range of topics can be addressed in SSCs. These may include:

• A more in-depth study of subjects included in the core curriculum. With a reduction in time allocated to basic sciences in the curriculum, students with an interest in the area have an opportunity to study anatomy or another basic science in more depth.

• Special aspects of clinical practice such as plastic surgery not covered in the curriculum.

• Topics unrelated to medicine but of possible relevance to a doctor’s future career, for example the study of a foreign language or business studies.

• Medical education and teaching skills. We have seen students generating useful learning resource material during an SSC.

• Inter-professional experiences, for example working as a member of an inter-professional team or shadowing a nurse. The latter proved a popular SSC in one school but mainly for female students!

Assessment of SSCs

A range of methods may be used. Portfolio assessment, as described in Chapter 31, offers a number of advantages. Problems relating to fairness and equivalence need to be addressed given the varying nature of different electives.

Integration of electives with the core

SSCs can be integrated in the timetable with the core curriculum in different ways:

• Sequential. A block of core teaching, for example 8 weeks, is followed by a 2-week SSC option. This allows the student to explore the subject of the preceding block in more detail, or to study an unrelated subject.

• Intermittent. Blocks of time, for example 4–10 weeks, are allocated for SSCs at set times in the curriculum.

• Concurrent. The SSC topic is scheduled to run on half or one day per week alongside the core but on a topic not necessarily related to the core.

• Integrated. The SSC is integrated within the core topic programme allowing the student to study different aspects of the core in more depth. One option in an endocrinology course we offer is for the student to look at the laboratory investigation of endocrine disease, another to look at surgery and a third to look at the management of endocrine problems in the community.

Reflect and react

1. Whether you are working in undergraduate or postgraduate training, has the appropriate balance between the core curriculum and SSCs been achieved in your programme?

2. Are the learning outcomes for the SSCs clear to the students and supervisors, and are they assessed appropriately?

3. Is a sufficient choice of SSCs available to students and are they given sufficient guidance to make their choice?

Cholerton S., Jordan R. Core curriculum and student-selected components. In: Dent J.A., Harden R.M., editors. A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. third ed. London: Elsevier; 2009:193-201. (Chapter 25)

Harden R.M., Davis M. The core curriculum with options or special study modules. AMEE Education Guide No. 5. Med. Teach.. 2001;23:231-244.

A description of the concept and how it can be implemented in practice.

Riley S.C. Student selected components. AMEE Guide No. 46. Med. Teach.. 2009;31:885-894.