14 Building learning around problems and clinical presentations

Problem-based-learning (PBL)

Definition

Problem-based learning has been widely adopted in medical education as an education strategy but its use has not been without controversy. The principal idea behind PBL is that the starting point for the learning is a clinical problem. This is the focus for the student’s learning and drives the learning activities on a ‘need to know’ basis. PBL has made a major contribution to medical education, but there has been a lack of clarity or a conceptual fog surrounding what is meant by the term. The underpinning educational principle is that students, when presented with examples from clinical practice, work out the principles or rules from the basic and clinical sciences that allow them to understand and interpret the problem (Fig. 15.1).

Reasons for a move to PBL

PBL offers a number of advantages, if implemented correctly:

• Students find the process enjoyable and motivating.

• Students are actively engaged in the learning. Activity is one of the FAIR principles for effective learning described in Chapter 2.

• Learning is related to medical practice and is seen by students as relevant – another FAIR principle.

• PBL addresses learning outcomes such as teamwork and problem solving, competencies often overlooked in the conventional curriculum.

• PBL encourages the development of an integrated body of knowledge that is usable in future clinical practice.

Implementation of PBL

1. Students receive the problem scenario. Traditionally this has been in print format, typically a short description of a patient’s presentation. The problem may be presented using a multi-media approach with a computer, video-tape or simulator. Simulated patients have also been used.

2. Students identify and clarify unfamiliar terms, then define and agree the problem or problems to be discussed. It is important that students do not spend too much time figuring out what they should learn at the expense of time spent learning.

3. Students consider possible explanations of the situation presented on the basis of their prior knowledge and identify areas where further learning is required. The tutor helps to ensure that the learning outcomes identified by the student are appropriate taking into account the learning outcomes for the course and what is achievable in the time available.

4. Students work independently and gather information relating to the learning outcomes. The group may agree to subdivide the task and allocate different responsibilities to individual members. Some of this work may be done online in the small group setting using a search engine such as Google.

5. The group reconvenes and shares the results of their private study. What they learn is then applied to the problem presented.

6. Additional information about the patient may be presented to the students and the above process is repeated.

Various points have been defined on the continuum between a problem-based approach and an information-orientated approach as described in the SPICES model (Harden and Davis 1999). This is summarised in Appendix 9. PBL is usually adopted in the context of an integrated medical curriculum but the strategy can also be used in a curriculum where the emphasis is on subjects or disciplines.

The role of the teacher

• Facilitating the learning in the small group. There is general agreement that the tutor must have skills in facilitation. The tutor need not be a subject expert in the area but some medical knowledge is helpful (although not everyone agrees with this). The greatest problem to arise in the delivery of PBL relates to the quality of the input from the teachers and their ability to act as facilitators in the PBL setting. PBL sessions should not degenerate into a tutorial dominated by the tutor. Staff training to prevent this happening is important.

• Assessment of the student. The teacher may be responsible for assessing and recording the performance of the PBL group and the individual student’s performance in the group. This may relate both to their mastery of the subject and to their performance and their skills as a group member. Student assessment is discussed in Section 5.

• Provision of resource materials. An area of controversy is the extent to which resource materials relating to the subject should be made available to students. Some teachers favour supporting students’ learning by providing extensive handouts and background information that covers the key areas to be studied. Others believe that students should not be ‘spoon fed’ and that it should be left to the student to identify and locate relevant material. If students are to achieve the expected learning outcomes within the set timescale, it is important that they are not faced with unnecessary difficulties or barriers.

• Presentation of the problem. The teacher may also have an input to the development of the problem and to its presentation in print or multi-media format.

• Curriculum planning. The contribution of PBL to the course learning outcomes needs to be made explicit. PBL small group work needs to be integrated with other elements within the curriculum. Lectures may still have a useful part to play as well as clinical and other practical work.

Task-based learning

Definition

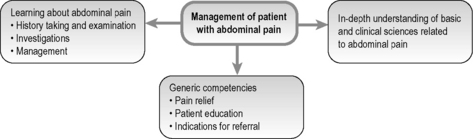

Task-based learning (TBL) incorporates the same educational philosophy as PBL and indeed has been described as part of the PBL continuum as illustrated in Appendix 9 (Harden and Davis 1999). In task-based learning the focus for the learner is not a paper problem simulation but the description of a task addressed by healthcare professionals. An example is ‘the management of a patient with abdominal pain’. In task-based learning the objective is not simply to learn to perform the task but to learn about the basic and clinical sciences relevant to the task and in so doing to gain a more in-depth understanding of the task (Figure 14.1). TBL recognises the need to know not only how to do something but also the principles or basis underlying the required action. In the abdominal pain example, the student’s attention is focused on issues such as the relevant anatomy and physiology of the abdomen, on the understanding of the mechanism of pain, on abdominal pathologies, and on the different approaches to investigation and management of a patient with abdominal pain.

TBL in a clinical setting

TBL is useful as an approach to curriculum integration and PBL in the clinical clerkships (Harden et al 2000). In the example given of the management of a patient with abdominal pain, students may concentrate on different aspects of the task in each of the clerkships through which they rotate:

• Acute abdominal pain and the emergency diagnosis and management in a surgical clerkship.

• Approaches to the investigation of a patient in a medical clerkship.

• Specific aspects relating to gynaecological causes in a gynaecological clerkship.

• Age-related differences in a geriatric or paediatric attachment.

• Psychosomatic aspects in a psychiatry attachment.

• The roles of different members of the healthcare team, early diagnosis, decision making and coping with uncertainty in a General Practice attachment. When for example should a patient complaining of abdominal pain be investigated and referred to hospital?

• Geographical and cultural differences in an overseas elective

Implementation of TBL

Medical schools that adopt a TBL approach generate usually about 100–150 clinical presentations as the focus for the curriculum. A list of the 104 presentations adopted in one school is given in Appendix 3. Grids or blueprints should be produced that identify how each task contributes to the learning outcomes and to the range of learning experiences in which the students engage. As described above, abdominal pain is a focus for the students’ learning in a range of clinical clerkships, each contributing in a different way to the students’ mastery of the learning outcomes of the course.

TBL provides a structure and focus for postgraduate education that previously was all too often lacking. It helps resolve what may be perceived to be a conflict between service delivery and the education of the student or trainee. Six tasks performed routinely by trainee dentists were identified as the basis for a postgraduate dental training programme. The expected learning outcomes were specified for each task as illustrated in the grid in Appendix 11.

The tasks specified in the curriculum documents can provide a framework for a student’s portfolio and this can be used for assessment as described in Chapter 31.

Reflect and react

1. PBL has proved attractive as an educational strategy for many teachers who have been intent on improving their courses. Others have been reluctant to adopt a teaching approach that seems alien to what they believe to be ‘good teaching’. Where do you stand? If you are a sceptic you may be converted if you see examples of good PBL in practice and talk with the students and other teachers who are involved.

2. Where are you on the PBL continuum as described in Appendix 9?

3. If you have adopted PBL in your teaching do you make full use of the new technologies to present the problem to the learner?

4. If you have undergraduate or postgraduate responsibilities for clinical teaching, you may wish to explore the concept of TBL. It may also be used to introduce a clinical focus in the early years of the curriculum.

Colliver J.A. Effectiveness of problem-based learning curricula: research and theory. Acad. Med.. 2000;75:259-266.

A review of problem-based learning.

Davis M.H., Harden R.M. Problem-based Learning: A Practical Guide. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 15. Dundee: AMEE, 1999.

The underpinning principles and an outline of the advantages and disadvantages of the approach.

Harden R.M., Davis M.H. The continuum of problem-based learning. Med. Teach.. 1999;20:317-322.

A model for analysing the level at which PBL is introduced into a curriculum.

Harden R.M., Crosby J.R., Davis M.H., et al. Task-based learning: the answer to integration and problem-based learning in the clinical years. Med. Educ.. 2000;34:391-397.

A description of TBL in the clinical years of a medical school’s programme.

Harden R.M., Laidlaw J.M., Ker J.S., Mitchell H.E. Task Based Learning: An educational Strategy for Undergraduate, Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 7. Dundee: AMEE, 1998.

An introduction to TBL. Eight aspects of implementing TBL are described in this Guide.

Taylor D., Miflin B. Problem-Based Learning: Where Are We Now?. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 36. Dundee: AMEE, 2010.

A current review of the role of problem-based learning in medicine.