37 Bronchiolitis and Wheezing

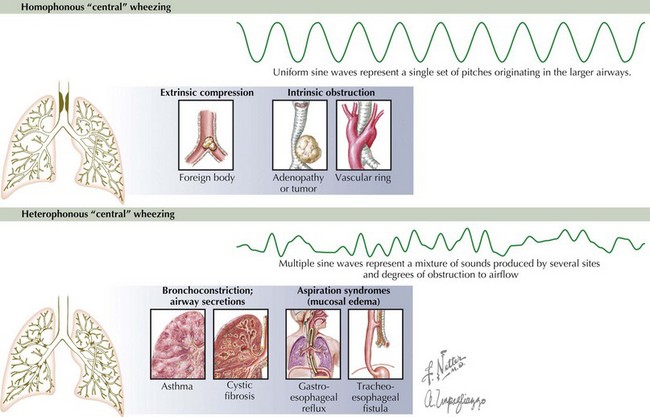

Wheezing is heterophonous or polyphonic in nature when there is diffuse narrowing of the airways. This widespread involvement of the airways produces a mixture of sounds associated with various degrees of obstruction to airflow. Multiple varied degrees of obstruction typically occur in the presence of bronchospasm, edema, or intraluminal secretions. The most common causes of heterophonous wheezing in the pediatric population are viral bronchiolitis and asthma (see Chapter 38). Conversely, homophonous wheezing refers to a single set of pitches that originates in the larger airways but that can be transmitted widely. Common causes of homophonous wheezing include tracheomalacia, bronchomalacia, foreign body aspiration, and anatomic compression of the airways (Figure 37-1).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The majority of wheezing in infants is caused by viral bronchiolitis or asthma, but many other entities can also cause wheezing at this age (Box 37-1).

Box 37-1 Differential Diagnosis of Wheezing in Infants and Young Children

Bronchiolitis

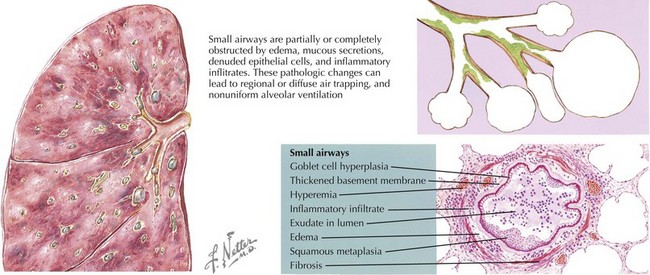

The infectious cause of acute bronchiolitis typically includes viruses with specific tropism for bronchiolar epithelium. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is responsible for more than 50% of cases, but other viruses are increasingly recognized as causes of this clinical entity. Viral infection of the lower airways can induce severe changes in the epithelial cell and mucosal surfaces of the human respiratory tract. Bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis, ciliary disruption, and peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltration are the earliest lesions. Edema of the small airways and mucus secretion, mixed with denudated epithelial cells, elicits obstruction and narrowing of the airways (see Figure 37-2). The generation of atelectasis is often associated with ventilation/perfusion mismatch and consequent hypoxemia. Heterogeneous ventilation and dynamic collapse of the airways during exhalation can lead to air trapping and pulmonary hyperinflation (see Figure 37-2). With severe obstructive lung disease and respiratory muscle fatigue, hypercapnia can also arise.

Asthma

Asthma is another important cause of wheezing in infants and children (see Chapter 38). This clinical entity is characterized by recurrent episodes of airway obstruction that are at least partially reversible with bronchodilators. Another pathogenic feature of the disease is chronic inflammation of the airways. Whereas extensive bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis and T-helper cell type 1 (Th1) cytokines like interferon-γ are present in viral bronchiolitis, inflammation in asthma is often driven by allergic (Th2) cytokines such as interleukin-13 (IL-13), IL-4, and IL-5. Other abnormalities of the asthmatic airway include constriction and hypertrophy of the airway smooth muscle, mucosal edema, hypertrophic mucous glands, and sometimes eosinophilic infiltration.

Other Causes of Wheezing

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is another important cause of acute or chronic wheezing in infants and children. Wheezing in GER is caused by pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents or by a vagal reflex that induces bronchospasm without aspiration. Other conditions associated with widespread involvement of the intrathoracic small airways such as cystic fibrosis (CF), primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), or immunodeficiency can present with heterophonous wheezing as well (see Figure 37-1).

The presence of homophonous wheezing is suggestive of narrowing or obstruction in the large central airways. Homophonous wheezing is commonly heard in children with tracheomalacia, bronchomalacia or anatomic abnormalities (i.e., vascular ring). In addition, an isolated homophonous wheeze localized in just one area may signal bronchial obstruction by an extrinsic compression or intraluminal foreign body (see Figure 37-1).

Clinical Presentation

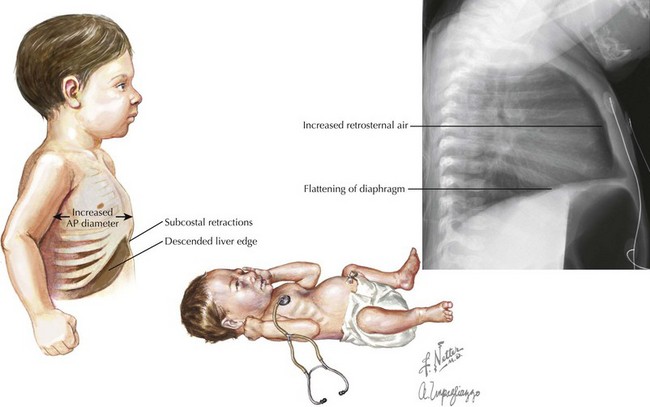

When evaluating an infant with an acute respiratory illness a critical question to answer is whether or not there is involvement of the lower airways. In RSV infection, non-specific upper respiratory tract symptoms consisting of nasal discharge and mild cough begin about 3 to 5 days after exposure. The progression of the disease to the lower respiratory tract is characterized by the presence of tachypnea, hypoxemia, nasal flaring and intercostal or subcostal retractions. The typical course for a previously healthy infant older than 6 months is one of improvement over the subsequent 2 to 5 days. Significant hypoxemia, grunting and marked use of accessory muscles are signs of severe disease and impending respiratory failure (Figure 37-3). Central apnea can also be an early manifestation of RSV infection, at times also resulting in respiratory failure.

Viral bronchiolitis is one of several syndromes associated with obstruction of the intrathoracic small airways; thus, the presence of expiratory heterophonous wheezing is a common but non-specific sign of the disease. Wheezing in infants can be better appreciated on pulmonary auscultation when elicited by gentle chest compression (so-called “squeeze the wheeze”) to induce forced expiratory flow. A marked reduction in amplitude of breathing sounds suggests very severe disease with nearly complete bronchiolar obstruction. Auscultation in bronchiolitis may also reveal inspiratory crackles as small airways re-open, and prolongation of the expiratory phase. The other cardinal feature of small airways obstruction is pulmonary hyperinflation. This clinical feature helps to localize the disease in the small airways as it is a manifestation of alveolar air trapping. The key signs of hyperinflation are an increase in antero-posterior diameter of the chest wall, the presence of subcostal retractions and the palpation of a normal sized liver below the costal margin (see Figure 37-3).

Congenital malformations cause homophonous wheezing in early infancy when they externally compress the airway or cause intrinsic obstruction of the airway lumen. Vascular rings secondary to abnormal development of the aortic arch can produce considerable constriction of the subjacent trachea (see Figure 37-1). Virtually any type of congenital intrathoracic lesion, depending on its size and location, can potentially cause external compression of the airways. Other causes of external compression include mediastinal lymphadenopathy secondary to infections (e.g., tuberculosis) or malignancies (e.g., lymphoma) (see Figure 37-1). Intrinsic obstruction of the airway lumen may be caused by foreign body aspiration, hemangiomas, and rarely carcinoid tumors (see Figure 37-1). Airway hemangiomas should be suspected particularly when they are present in other areas of the body (e.g., skin).

Castro-Rodriguez JA, Rodrigo GJ. Efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in infants and preschoolers with recurrent wheezing and asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e519-e525.

Meissner HC. Bronchiolitis. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009:241-245.

Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al. Oral prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus-induced wheezing. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):329-338.

Panitch HB. The relationship between early respiratory viral infections and subsequent wheezing and asthma. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46(5):392-400.

Panitch HB. Treatment of bronchiolitis in infants. Pediatr Case Rev. 2003;3(1):3-19.

Plint AC, Johnson DW, Patel H, et al. Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC): Epinephrine and dexamethasone in children with bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(20):2079-2089.

Weinberger M, Abu-Hasan M. Pseudo-asthma: when cough, wheezing, and dyspnea are not asthma. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):855-864.

Zhang L, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Wainwright C, et al: Nebulized hypertonic saline solution for acute bronchiolitis in infants, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(4):CD006458, 2008.