Chapter 393 Bronchiectasis

Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis

In the developed world, cystic fibrosis (Chapter 395) is the most common cause of clinically significant bronchiectasis. Other conditions associated with bronchiectasis include primary ciliary dyskinesia, foreign body aspiration, aspiration of gastric contents, immune deficiency syndromes (especially humoral immunity), and infection, especially pertussis, measles, and tuberculosis. Bronchiectasis can also be congenital, as in Williams-Campbell syndrome, in which there is an absence of annular bronchial cartilage, and Marnier-Kuhn syndrome (congenital tracheobronchomegaly), in which there is a connective tissue disorder. Other disease entities associated with bronchiectasis are right middle lobe syndrome (chronic extrinsic compression of right middle lobe bronchus by hilar lymph nodes) and yellow nail syndrome (pleural effusion, lymphedema, discolored nails).

Diagnosis

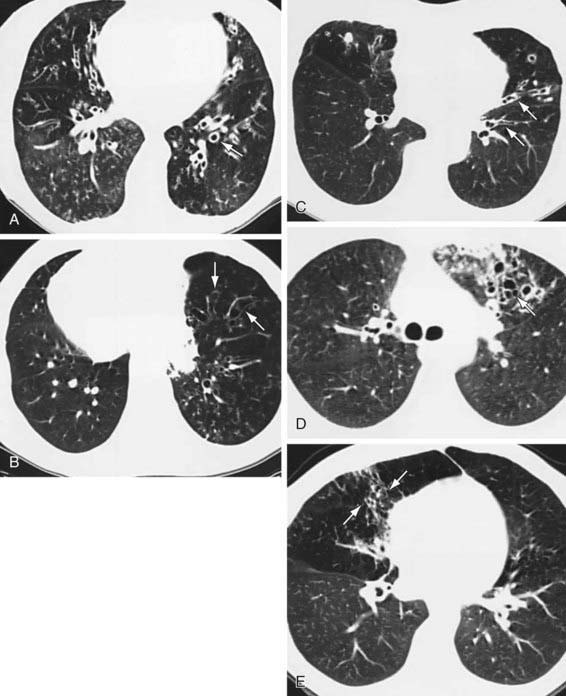

Conditions that can be associated with bronchiectasis should be ruled out by appropriate investigations (e.g., sweat test, immunologic work-up). Chest radiographs of patients with bronchiectasis tend to be nonspecific. Typical findings can include increase in size and loss of definition of bronchovascular markings, crowding of bronchi, and loss of lung volume. In more severe forms, cystic spaces, occasionally with air-fluid levels and honeycombing, may occur. Compensatory overinflation of unaffected lung may be seen. Thin-section HRCT scanning is the gold standard, because it has excellent sensitivity and specificity. CT provides further information on disease location, presence of mediastinal lesions, and the extent of segmental involvement. The addition of radiolabeled aerosol inhalation to CT scanning can provide even more information. The CT findings in patients with bronchiectasis typically include cylindrical (“tram lines,” “signet ring appearance”), varicose (bronchi with “beaded contour”), cystic (cysts in “strings and clusters”), or mixed forms (Fig. 393-1). The lower lobes are most commonly affected.

Barker AF. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of bronchiectasis. UpToDate, last revised December 30, 2008, http://www.uptodate.com.

Bilton D. Update on non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Curr Opin Pulmon Med. 2008;14:595-599.

Boren EJ, Teuber SS, Gershwin ME. A review of non-cystic fibrosis pediatric bronchiectasis. Clin Rev Allerg Immunol. 2008;34:260-273.

Evans DJ, Bara AI, Greenstone M: Prolonged antibiotics for purulent bronchiectasis in children and adults, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD001392, 2007.

Fall A, Spenser D. Paediatric bronchiectasis in Europe: what now and where next? Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006;7:268-274.

Guran T, Turan S, Karadag B, et al. Bone mineral density in children with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respiration. 2008;75:432-436.

Kapur N, Bell S, Kolbe J, et al: Inhaled steroids for bronchiectasis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD000996, 2009.

Rama M, Yousef E. Bronchiectasis and chronic asthma: how common in pediatrics? Allergy Asthma Proc. 2006;27:354-358.

Santamaria F, Montella S, Camera L, et al. Lung structure abnormalities, but normal lung function in pediatric bronchiectasis. Chest. 2006;130:480-486.

Sirmali M, Karasu S, Turut H, et al. Surgical management of bronchiectasis in childhood. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2007;31:120-123.

Stafler P, Carr SB. Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: its diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:73-82.