CHAPTER 6 Bridging External Fixation with Pin Augmentation

External fixation is fundamental to the principles of orthopaedic trauma. It provides a rapid, simple, and effective surgical treatment for osseous, articular, and soft tissue injuries. Patients with fractures and injuries of the distal radius have and continue to achieve good results after immediate and definitive treatment with external fixation.1–4

The term “bridging” refers to the design of the frame in which the radiocarpal joint is spanned, and fracture stability is achieved via distraction and ligamentotaxis, which refers to the support provided by soft tissue tension to align and hold the reduction.5 Additional fixation is supplemented by Kirschner wire (K-wire) pins, which are percutaneously or internally placed into the distal radius. This is the concept referred to collectively as “bridging external fixation with pin fixation” or “augmented external fixation.”6 “Nonbridging external fixation” refers to a frame design that fixes the metaphyseal/articular fragments to the proximal diaphysis without spanning the wrist joint, sparing the capsule and the ligaments from the potentially damaging effects of traction.7–11

Although the specific roles of external and internal methods of fixation in the treatment of distal radius fractures continue to evolve, restoration of articular congruity, radial length, radial height, and dorsal tilt remains a common tenet to all modes of treatment.12 After Vidal and colleagues5 introduced the concept of ligamentotaxis as a means to align bony fragments using soft tissue tension, the use of the external fixator soared. A decade later after widespread adoption of the technique internationally, an increased awareness of its limitations and attendant complications, such as loss of reduction, digital and wrist stiffness, and complex regional pain syndrome, unfolded.13,14

As we have developed an improved and more sophisticated understanding of fracture healing and wrist biomechanics, we have been better able to refine the application of external fixation for distal radius fractures. Its combined use with limited internal,15 arthroscopic,16–20 and percutaneous fracture reduction techniques,21 and supplemental bone graft or bone graft substitutes has enhanced the stability of the fixation construct,22–30 and simultaneously minimized the dependency on traction for maintenance of reduction.

Despite its effectiveness, and similar to other forms of treatment, external fixation has its problems and concerns. These include poor patient tolerance or acceptance, pin tract infection, iatrogenic injury to the small branches of the superficial radial nerve, loss of fixation, settling, radioulnar joint dysfunction, radiocarpal arthrofibrosis, and, as stated previously, hand and digital stiffness.13,31–34 In addition, external fixation without supplementation inherently lacks the capacity to fix rigidly impacted or comminuted articular “die-punch” fragments and, by itself, has been associated with loss of articular reduction and articular incongruency.35 In the last few years, the ease of application and increased fixation strength of volar locking plates have led to an unprecedented increase in the popularity of internal fixation and a concomitant shift away from external fixation of distal radius fractures.

Although correct principles of application of augmented external fixation are in danger of becoming a lost art among orthopaedic surgical training programs, the technique continues to be the only viable treatment option in certain situations. In addition, more recent randomized clinical studies attest not only to its clinical utility, but also to improved functional and satisfaction outcomes compared with internal fixation.1–3 It is imperative that hand and upper extremity surgeons who routinely provide care for fractures and injuries of the distal radius be well versed in techniques of external fixation and prepared to use this form of treatment when applicable.

Basic Science

In contrast to nonbridging applications of external fixation to long bones, such as the tibia, femur, or humerus, peculiar to the distal radius is the need to span the neighboring radiocarpal and intercarpal joints, and the associated deleterious effect of distraction on the intrinsic and extrinsic carpal ligaments. Although it is important to gain reduction of fracture fragments, it is crucial that the principle of ligamentotaxis not compromise soft tissue viability or tendon gliding by prolonged maintenance of traction. Lengthy or excessive traction predictably results in digital stiffness and joint contractures,37 and the resultant dysfunction of the hand and wrist negates any of the goals of fracture healing with external fixation.

Principles of Augmented External Fixation

Augmentation with percutaneous or open pin fixation or bone graft or both is needed to provide increased stability to the external fixator construct and reduce the need for applied distraction.27,38 Although application of an external fixator can acutely restore radial height and correct angular rotation alignment, there is a tendency for the fracture fragments to settle over time because of the stress-relaxation of the surrounding collagenous soft tissue envelope.38 This settling of fracture fragments especially occurs when there is metaphyseal comminution and bone loss, which precludes firm bony contact, diminishing construct stability. In addition, traction alone does not restore articular congruency when there is impaction and displacement of intra-articular fragments, in which case a limited open incision is required to attain reduction.27,29

Biomechanical studies have shown that supplemental pin fixation decreases the dependency on ligamentotaxis for maintenance of reduction by minimizing the extremes of positioning and need for distraction.33 A pin placed through the radial styloid neutralizes the deforming force of the brachioradialis38 and the powerful wrist radial deviators of the first dorsal compartment. A single pin placed dorsally (dorsal transfixation wire [DTW]) provides a statistically significant increase in resistance to deformation, by gaining purchase on the stout volar metaphyseal cortex and directly opposing the strong dorsally deforming forces of the wrist and digital extensors. The increased stability gained by the augmentation pins more than offsets the biomechanical differences in the material strength of different external fixation models39; consequently, a fixator should be chosen because of ease of application and use, rather than because of its size or material properties.

Bone Grafting with Augmentation of External Fixation

Several studies have shown that the addition of bone graft or bone graft substitutes supports the articular surface and effectively prevents fragment settling.22,28,40 Leung and colleagues22–24 showed that bone graft application into the metaphyseal void that is created after reduction of dorsally displaced and articular impaction injuries enables earlier removal of the external fixator by expediting healing and providing firm support for the reduced articular surface. Subsequent studies have shown that bone graft substitutes are equally effective in provision of articular support and minimization of fracture fragment settling.25,30

Indications

The patient should be apprised of the different options and expected outcomes and be involved in the decision-making process. The patient may accept the additional risk of open reduction and internal fixation to allow for a shorter period of cast immobilization. The patient should understand that an initial attempt at minimally invasive percutaneous reduction before open reduction is an acceptable treatment algorithm that is well supported by clinical studies.1–3 Kreder and colleagues3 showed that if an optimal and stable reduction is achieved with percutaneous fixation, open reduction is unnecessary, and function is superior.

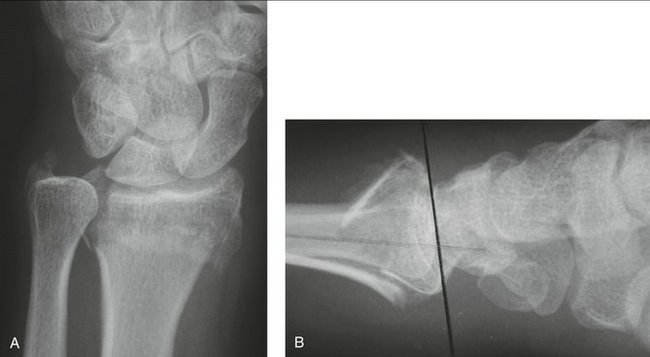

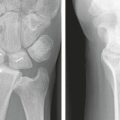

The ideal candidate for external fixation with pin augmentation is a patient who has an unstable intra-articular fracture of the distal radius (Fig. 6-1). Specific indications for operative management include articular depression (1 mm) after attempted closed reduction, or loss of reduction, defined as a dorsal tilt exceeding 10 degrees, loss of radial length exceeding 5 mm, or articular depression exceeding 1 mm.12,28 The technique of augmented external fixation is useful for a variety of fracture patterns, however, which may include intra-articular and extra-articular fractures that are displaced and unstable. Other indications for external fixation include injuries with soft tissue compromise, grossly contaminated open fractures, and unstable multitrauma patients who are brought to the operating room for other life-threatening injuries. These emergent situations potentially apply to patients of all age groups. Percutaneous techniques for fracture fixation should not be delayed longer than 10 to 14 days because of the early callus and soft tissue scarring that would preclude closed fracture manipulation and the effects of ligamentotaxis.

Surgical Technique

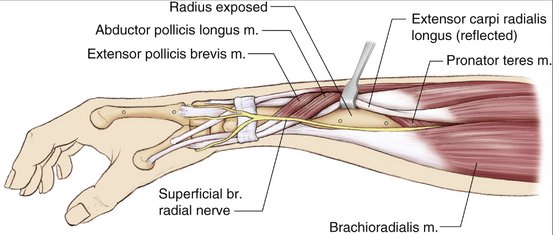

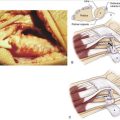

A 2.5-cm longitudinal incision is made at the level of the mid radial shaft about 10 cm proximal to the radial styloid and a minimum of 3 cm from the most proximal fracture line. We prefer this mini-incision approach over percutaneous placement of the external fixator pins because of the unpredictable proximity of the superficial branch of the radial nerve (SBRN) and the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.29 The preferred interval is between the extensor common radialis brevis and longus muscles,41 such that the fixator lies in an oblique plane midway between the coronal and sagittal planes of the forearm. A deep muscular interval between the brachioradialis and extensor radialis longus38 also is acceptable, although there is an increased risk of neurapraxic injury or irritation of the radial sensory nerve (Fig. 6-2). Soft tissue is reflected sharply off the bone without stripping periosteum to allow for secure positioning of the pin guide.

Two 4-mm-diameter pins are drilled across two cortices of the shaft. Whether the pins are placed in parallel or convergent depends on the particular fixator design, and there is some suggestion that the obliquity of convergent pin placement increases bone purchase. Although various pin sizes are available, 4-mm pins have been shown to have the best pullout strength and resistance to bending without increasing risk of pin site fracture.42 Pin placement is confirmed with fluoroscopy.

A 2-cm longitudinal incision is made in the oblique plane over the index metacarpal distal to the flare of the metacarpal base. The extensor tendon and first dorsal interosseous muscle are sharply reflected to allow exposure to the bone (see Fig. 6-2). Care is taken to avoid injury to the small branches of the SBRN. With the index metacarpophalangeal joint flexed to tension the intrinsics properly, two 3-mm pins are drilled across two cortices in a similar fashion as was done for the radius. Bicortical purchase is again confirmed with fluoroscopy.

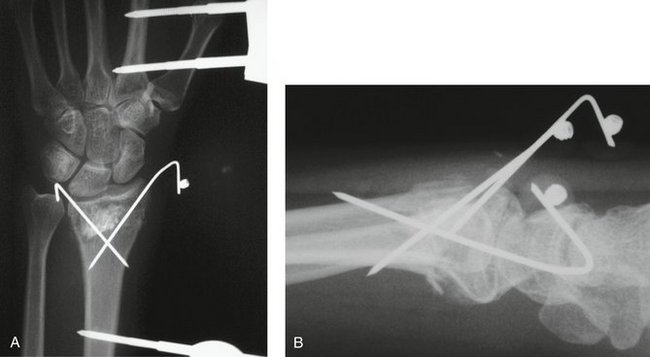

The external fixator frame is applied (Fig. 6-3). Most systems comprise a single radiolucent bar that is secured with metal clamps to the stainless steel pins. Subtle variations exist, and technical guidelines should be studied and learned before use.

The frame is first loosely applied to the pins, and the final reduction is guided by intraoperative fluoroscopy. A surgical assistant is helpful during the manipulation to provide a gentle countertraction force on the proximal forearm; the assistant also may be asked to secure and tighten the bar to the distal pins while the fracture reduction is held. An alternative method that may be useful when an assistant is unavailable is to suspend the hand with sterile finger traps and apply 5 to 10 lb of countertraction.21

Fracture reduction is achieved by a combination of longitudinal traction, ulnar deviation, and dorsal or volar translation of the carpus relative to the shaft of the radius.43,44 Manual pressure placed directly on the tip of the radial styloid by the surgeon’s thumb helps to restore radial length and inclination. When the fracture is displaced dorsally, a palmarly directed translation force on the carpus is helpful at this time to optimize reduction. When the fracture is displaced volarly, a dorsally directed translation force combined with slight wrist extension and supination is performed. The external fixator is then provisionally locked in position.

A closed reduction alone is usually attainable with fractures that have a simple intra-articular component.29 Additional reduction maneuvers are then required, however, to fix individual fracture fragments directly and obviate the need for maintenance of distraction or extremes of positioning. K-wire placement into the major fracture fragments can be used as joysticks to help guide reduction.

Because of the indirect nature of the external fixator, the frame alone is insufficient to reduce impacted articular fragments. After the larger fragments are aligned or provisionally fixed with K-wires, we perform percutaneous, limited open reduction as described by Fernandez and Geissler.21,45 Reduction of these fragments is achieved with a 2- to 3-cm longitudinal dorsal mini-incision that is based slightly ulnar to Lister’s tubercle. The interval between the third and fourth dorsal compartments is dissected, and the extensor pollicus longus tendon is transposed radially. The fracture lines in the metaphysis are identified and exposed, and lifting a single large dorsal cortical fragment (trapdoor) exposes the entire metaphysis and the impacted articular pieces. A Freer elevator or dental pick is used to elevate the impacted articular fragments (Fig. 6-4). The displaced fragment is reduced against the lunate; it is important at this phase of the procedure that traction is reduced to allow the lunate and scaphoid to act as a guide to a congruent reduction.

Bone graft or bone graft substitute is packed behind the reconstituted subchondral bone (Fig. 6-5). The articular surface is supported with a subchondral 0.045- or 0.062-cm K-wire placed transversely from the radial styloid directed toward the dorsal radial cortex of the sigmoid notch, taking care not to penetrate the radioulnar joint.21,45 Restoration of radiocarpal articular congruency is guided and confirmed with fluoroscopy. In addition, congruency of the distal radioulnar joint should be ensured at this stage.

FIGURE 6-5 Intraoperative fluoroscopic image after application of bone graft or bone graft substitute.

One (or two) additional K-wires are inserted through the tip of the radial styloid just dorsal to the crossing of the first dorsal compartment and positioned at a relatively acute angle to the radial shaft to cross the fracture and gain purchase in the strong diaphyseal ulnar cortex of the radial shaft. A 14-gauge or 16-gauge angiocatheter is important as a drill guide to prevent injury to the nearby branches of the radial sensory nerve. (If using more than one wire through the styloid, we prefer a parallel configuration.) A DTW is placed in a 45-degree angle to the sagittal plane of the radial shaft through the dorsal rim of the distal radius between the fourth and fifth dorsal compartments. This wire is positioned to cross the fracture site and capture the stout volar cortex of the radial shaft. The placement of this DTW in combination with the pin placed through the radial styloid (Fig. 6-6) has been shown to provide maximal stability to the external fixation construct.38

Lastly, the distal radioulnar joint should be assessed for stability after radiocarpal fixation. If grossly unstable, numerous techniques can be used to effect stability. Casting in the position of maximal stability (usually partial or complete supination) for 3 to 4 weeks is effective for restoration of stability.26,46,47 Alternatively, an ulnar styloid pin or two cross pins can be placed through radial and ulnar cortical shafts approximately 5 to 6 cm proximal to the joint and left proud to facilitate removal in the event of fatigue failure. Large basi-styloid fragments can be fixed with K-wires, tension bands, or a small cannulated screw as needed to reattach the disrupted dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments, which insert at its fovea.

Technical Pearls and Pitfalls

Postoperative Course and Rehabilitation

The wrist and hand should be elevated for the first 48 to 72 hours. Digital motion exercises are begun immediately after surgery. The skin sutures and postoperative dressing are maintained for 10 to 14 days, and then twice daily pin site care is begun with diluted hydrogen peroxide. If the distal radioulnar joint is determined to be stable at surgery, forearm supination and pronation exercises are begun at the first postoperative visit. Patients are encouraged to use their hand for light activities, such as eating, writing, dressing, and light typing. Lifting, squeezing, and gripping are prohibited until all hardware has been removed. Patients may shower with the frame in place, provided that all wounds are healed and dry, but should avoid immersion in standing water. Fracture healing and maintenance of fracture reduction are checked with plain radiographs every 2 to 3 weeks. Hand therapy is generally instituted early in the postoperative course, especially if stiffness or edema develops. Peroxide pin tract care is supplemented by a short course of oral antibiotics if pin erythema develops; frank pin tract infection requiring premature removal is rare.

Results

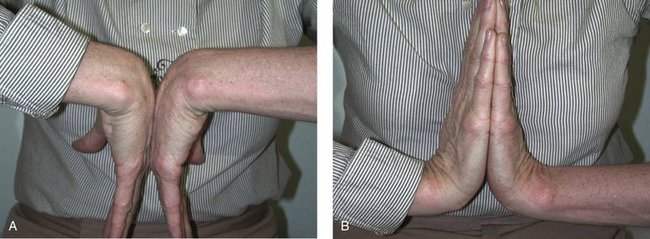

Although biomechanical studies suggest superior fixation strength with internal fixation compared with augmented external fixation,38,48 clinical studies show little significant difference in functional outcome between dorsal plating, augmented external fixation, or closed reduction and casting.1,4,49 With augmental external fixation, we have achieved excellent radiographic healing (Fig. 6-7) and restoration of functional wrist motion (Fig. 6-8). In a retrospective cohort of 21 patients consecutively treated with augmented external fixation and bone graft, wrist motion averaged 90% of the uninjured wrist, and grip strength measured 75% of the uninjured side. Of cases, 94% had good or excellent radiographic results by the modified Lidstrom radiographic scoring system and were rated as good or excellent by the criteria of Gartland and Werley. The average DASH functional/symptom score was 90.3 (maximum 100). Radiographic parameters were restored to an average of 12 mm radial length, 4 degrees volar tilt, 23 degrees radial inclination, and 0.6 mm ulnar-positive variance. Articular reduction was maintained in all patients.28

There are few level I studies that effectively compare internal fixation and external fixation; the studies that exist support percutaneous fixation over the added surgical dissection and risk of internal fixation, provided that articular congruence and stability can be achieved.1,3 Although a few more recent studies suggest superiority of locked volar plate fixation,50,51 no randomized trials have been reported to date. More data are needed to compare sufficiently various fixation techniques that are stratified to patient demographics and specific fracture patterns. Under many circumstances, external fixation with pin augmentation continues to be an ideal method of treatment, supported by decades of clinical and basic research. With proper planning and surgical technique, excellent results can be achieved in a wide variety of fracture patterns.

1. Grewel R, Perey B, Wilmink M, et al. A randomized trial on the treatment of intra-articular distal radius fractures: open reduction internal fixation with dorsal plating versus mini open reduction, percutaneous pinning and external fixation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:764-772.

2. Kapoor H, Agarwal A, Dhaon BK. Displaced intra-articular fractures of distal radius: a comparative evaluation of results following closed reduction, external fixation and open reduction with internal fixation. Injury. 2000;31:75-79.

3. Kreder HJ, Hanel DP, Agel J, et al. Indirect reduction and percutaneous fixation versus open reduction and internal fixation for displaced intra-articular fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:829-836.

4. Margaliot Z, Haase SC, Kotsis SV, et al. A meta-analysis of outcomes of external fixation versus plate osteosynthesis for unstable distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:1185-1199.

5. Vidal J, Buscayret C, Fischbach C, et al. New method of treatment of comminuted fractures of the lower end of the radius: “ligamentary taxis.”. Acta Orthop Belg. 1977;43:781-789.

6. Seitz WHJr, Froimson AI, Leb R, et al. Augmented external fixation of unstable distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:1010-1016.

7. McQueen MM. Non-spanning external fixation of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 2005;21:375-380.

8. McQueen MM. Metaphyseal external fixation of the distal radius. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1999;58:9-14.

9. McQueen MM. Redisplaced unstable fractures of the distal radius: a randomised, prospective study of bridging versus non-bridging external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:665-669.

10. Slutsky DJ. Nonbridging external fixation of intra-articular distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2005;21:381-394.

11. Gradl G, Jupiter JB, Gierer P, et al. Fractures of the distal radius treated with a nonbridging external fixation technique using multiplanar K-wires. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:960-968.

12. Lafontaine M, Hardy D, Delince P. Stability assessment of distal radius fractures. Injury. 1989;20:208-210.

13. Cooney WPIII, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. Complications of Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62:613-619.

14. Sanders RA, Keppel FL, Waldrop JI. External fixation of distal radial fractures: results and complications. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:385-391.

15. Cooney WP, Berger RA. Treatment of complex fractures of the distal radius: combined use of internal and external fixation and arthroscopic reduction. Hand Clin. 1993;9:603-612.

16. Wolfe SW, Easterling KE, Yoo H. Arthroscopic-assisted reduction of distal radius fractures. J Arthr Rel Surg. 1995;11:706-714.

17. Freeland AE, Geissler WB. The arthroscopic management of intra-articular distal radius fractures. Hand Surg. 2000;5:93-102.

18. Geissler WB. Arthroscopically assisted reduction of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 1995;11:19-29.

19. Geissler WB, Freeland AE. Arthroscopic management of intra-articular distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 1999;15:455-465. viii

20. Geissler WB, Freeland AE. Arthroscopically-assisted reduction of intraarticular distal radial fractures. Clin Orthop. 1996;327:125-134.

21. Geissler WB, Fernandez DL. Percutaneous and limited open reduction of the articular surface of the distal radius. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5:255-264.

22. Leung KS, Shen WY, Leung PC, et al. Ligamentotaxis and bone grafting for comminuted fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:838-842.

23. Leung KS, Shen WY, Tsang HK, et al. An effective treatment of comminuted fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:11-17.

24. Leung KS, So WS, Chiu VD, et al. Ligamentotaxis for comminuted distal radial fractures modified by primary cancellous grafting and functional bracing: long-term results. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5:265-271.

25. Pike LM, Wolfe SW. Alternatives to bone graft in the treatment of distal radius fractures. Atlas Hand Clin. 1997;2:125-150.

26. Ruch DS, Weiland AJ, Wolfe SW, et al. Current concepts in the treatment of distal radial fractures. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:389-401.

27. Swigart CR, Wolfe SW. Limited incision open techniques for distal radius fracture management. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32:317-327. ix

28. Wolfe SW, Pike L, Slade JFIII, et al. Augmentation of distal radius fracture fixation with coralline hydroxyapatite bone graft substitute. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:816-827.

29. Seitz WHJr, Putnam MD, Dick HM. Limited open surgical approach for external fixation of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:288-293.

30. Herrera M, Chapman CB, Roh M, et al. Treatment of unstable distal radius fractures with cancellous allograft and external fixation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:1269-1278.

31. Sanders RA, Keppel FL, Waldrop JI. External fixation of distal radial fractures: results and complications. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:385-391.

32. Seitz WHJr. Complications and problems in the management of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 1994;10:117-122.

33. Seitz WHJr, Froimson AI, Leb RB. Reduction of treatment-related complications in the external fixation of complex distal radius fractures. Orthop Rev. 1991;20:169-177.

34. Weber SC, Szabo RM. Severely comminuted distal radial fracture as an unsolved problem: complications associated with external fixation and pins and plaster techniques. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1986;11:157-165.

35. Catalano LW, Cole RJ, Gelberman RH, et al. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the distal aspect of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:1290-1302.

36. Pollak AN, Ziran BH. Principles of external fixation. In Browner B, Jesse B, Jupiter JB, et al, editors: Skeletal Trauma, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2003.

37. Kaempffe FA, Wheeler DR, Peimer CA, et al. Severe fractures of the distal radius: effect of amount and duration of external fixator distraction on outcome. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1993;18:33-41.

38. Wolfe SW, Swigart CR, Grauer BS, et al. Augmented external fixation of distal radius fractures: a biomechanical analysis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:127-134.

39. Wolfe SW, Austin G, Lorenze MD, et al. Comparative stability of external fixation: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:516-524.

40. Ladd AL, Pliam NB. The role of bone graft and alternatives in unstable distal radius fracture treatment. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;30:337-351.

41. Raskin KB, Rettig ME. Distal radius fractures: external fixation and supplemental K-wires. Atlas Hand Clin. 2006;11:187-196.

42. Seitz WHJr, Froimson AI, Brooks DB, et al. Biomechanical analysis of pin placement and pin size for external fixation of distal radius fractures. Clin Orthop. 1990;251:207-212.

43. Agee JM, Szabo RM, Chidgey LK, et al. Treatment of comminuted distal radius fractures: an approach based on pathomechanics. Orthopedics. 1994;17:1115-1122.

44. Agee JM. Distal radius fractures: multiplanar ligamentotaxis. Hand Clin. 1993;9:577-585.

45. Fernandez DL, Geissler WB. Treatment of displaced articular fractures of the radius. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:375-384.

46. Cole DW, Elsaidi GA, Kuzma KR, et al. Distal radioulnar joint instability in distal radius fractures: the role of sigmoid notch and triangular fibrocartilage complex revisited. Injury. 2006;37:252-258.

47. Ruch DS, Lumsden BC, Papadonikolakis A. Distal radius fractures: a comparison of tension band wiring versus ulnar outrigger external fixation for the management of distal radioulnar instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:969-977.

48. Dodds SD, Cornelissen S, Jossan S, et al. A biomechanical comparison of fragment-specific fixation and augmented external fixation for intra-articular distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:953-964.

49. Harley BJ, Scharfenberger A, Beaupre LA, et al. Augmented external fixation versus percutaneous pinning and casting for unstable fractures of the distal radius—a prospective randomized trial. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:815-824.

50. Orbay JL, Fernandez DL. Volar fixed-angle plate fixation for unstable distal radius fractures in the elderly patient. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:96-102.

51. Wright TW, Horodyski M, Smith DW. Functional outcome of unstable distal radius fractures: ORIF with a volar fixed-angle tine plate versus external fixation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:289-299.