CHAPTER 18 Breastfeeding and Botanical Medicine

BREASTFEEDING AND HERBS: A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS AND BREASTFEEDING CONCERNS FOR THE MOTHER–INFANT DYAD

Lactation is a healthy function of the postnatal female body; it benefits the woman and provides the child with the only known perfect food for humans—human milk.1 The breast and breast milk are what the human baby is evolutionarily adapted to “expect” after birth. Breastfeeding is what the woman’s body also “expects” after birth. Although a full description of benefits of breastfeeding is well beyond the scope of this chapter, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) statement on breastfeeding provides a succinct summary (Box 18-1).1

BOX 18-1 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Policy Statement on Breastfeeding

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics Work Group on Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk, Pediatrics 100(6):1035-1039, 1999.

The AAP identifies breastfeeding as the ideal method of feeding and nurturing infants and recognizes breastfeeding as primary in achieving optimal infant and child health, growth, and development. The following are excerpts from the extensive AAP policy statement on breastfeeding, Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, Section on Breastfeeding Pediatrics 115;496-506, 2005. The full text is available at http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/2/496. Many of these recommendations are identical for high-risk infants, and a section devoted to the nursing of these babies is included in the AAP statement.

Recommendations on Breastfeeding for Healthy Term Infants

Role of Pediatricians and Other Health Care Professionals in Protecting, Promoting, and Supporting Breastfeeding

General

Education

Clinical Practice

As a society, encouraging breastfeeding of our young is one of the most important health measures we can take. The established risks of not breastfeeding include increased incidence of otitis media, GI infections, respiratory infections, juvenile diabetes, lymphoma, and lowered cognitive function for the baby; the mother is at increased risk for breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and osteoporosis. The beneficial effects of breastfeeding are generally dose related: Exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months, followed by significant breastfeeding for at least the first year and beyond is recognized as optimal.1,2 This “dose” provides the gold standard of nutrition, with which all else must be compared. Benefits to both mother and child are now considered so extensive that the protection, promotion, and support of breastfeeding is a recognized global health activity in all countries; the WHO and UNICEF are but two global organizations that have consistently worked toward the goal of increasing breastfeeding rates and duration. Chemical risk to the breastfeeding dyad must be considered relative to the importance of breastfeeding in the optimal manner for the optimal duration.

HERBS AND BREASTFEEDING

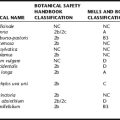

Concerns involving herbs and breastfeeding have become commonplace among health care providers. Written information to date is often inadequate for counseling clients/patients: herbal product label information provides insufficient safety information, and reference texts generally present extremely limited data focused only on infant risk. 3 4 5 6 Few authors explain the rationale behind contraindications, nor do they provide documentation of adverse reactions, and the criteria for determining risk is typically not defined. Exceptions are McKenna et al.,7 which features an introductory essay on the parameters of herb risk during lactation as well as more detailed discussion of lactation use for each monographed herb, and Mills and Bone,8 with its extensive chapter on the safety of herbs during pregnancy and lactation. Some texts discourage or contraindicate all herb use during lactation, rendering such books particularly useless.9 In sharp contrast, the Herbal PDR only rarely mentions that use of an herb may require caution during lactation, even when perhaps when it is merited. The German Commission E3 as well as AHPA’s Botanical Safety Handbook10 provide generally reliable guidelines for the safe use of herbs during lactation.

Detailed information is now available on pharmaceutical drug use during lactation, providing the health care practitioner with sufficient information to counsel breastfeeding mothers. Most prescription drugs have been demonstrated to carry some degree of compatibility with breastfeeding.11,12 Lactation pharmacology generally has shown limited drug entry into breast milk and few adverse reactions in the infant for most chemical entities. Weaning in order to use a medication is only rarely considered necessary.11 Given this, herb safety cannot be evaluated in isolation from drug safety, and the relative safety of most herbs during lactation may be taken as an extension, because of the relatively limited side effects and adverse events from herbs as compared to pharmaceutical drugs.

Each mother–child nursing pair, or dyad, is considered a unit. Dyads are as unique as any individual, requiring information fitted to their own situation. Just as with drugs, categorical recommendations cannot be made about herbs. Ruth Lawrence, an internationally recognized expert in lactation, ended her discussion on herbs in a US government publication about risk with a simple summary statement: “The medicinal use of herbs per se is not a contraindication to breastfeeding.”13 Assessment of risk is possible but must be individualized using basic principles. This first requires an understanding of both lactation and lactation pharmacology.

HOW CHEMICALS ENTER BREAST MILK: WHAT WE KNOW

The science of lactation pharmacology and toxicology has greatly advanced over the last 20 years so that recognized principles of chemical entry into breast milk can be used to determine drug and environmental contaminant risk, even when some information is lacking.12 Recognition of these principles has greatly advanced the knowledge base and clinical practice of drug prescribing with breastfeeding women.

Almost any chemical a breastfeeding mother ingests that gains entry to her bloodstream will enter her milk to some degree; however, it appears that most substances will only gain entry in minute doses. The oft-quoted rule is 1% of the maternal dose of any medication will enter the milk, and with some exceptions, up to about 10%.12,14 Pharmaceuticals, especially single-chemical preparations noted for their “magic bullet” effect on target systems, can have profound effects on the mother, yet it is the exception when the infant-received dose is large enough to elicit any pharmacological effect. In general, no adverse effects are noted when the milk dose of a substance is less than 10% of the mother’s ingested dose. Such a dose is typically too small to elicit a pharmaceutical response. From ingestion to milk entry, the same pharmacologic principles for drugs apply to herbs, and there is no a priori reason to think that phytochemicals would be exceptional regarding milk entry.

Factors Affecting Impact on Child by Substances Taken by the Mother during Lactation

other volatiles, tend to diffuse more rapidly into and out of milk, with milk levels closely reflecting maternal serum levels. Lipid-soluble chemicals, such as most central nervous system drugs, also tend to enter into milk more readily, and can exhibit higher than expected levels. The blood–breast barrier somewhat resembles the blood–brain barrier in this regard.12

Chemical entry into milk is restricted by a secretory epithelium with tight junctures between the alveolar cells of the mammary structure. However, colostrum, produced in the first 3 to 10 days postpartum, is produced before these tight junctures close. Until the alveolar cells swell with high-volume milk production, maternal proteins such as immunoglobulins and most chemicals in the serum have enhanced access to the milk compartment, passing freely between the alveolar cells. Lactation experts agree that relatively larger doses of chemicals enter milk during this time.12,15 After this time, chemicals can only gain access to the milk compartment through the two cell membranes of the alveolar cells, usually by diffusion.

Asking the mother the age of the child as well as nursing pattern will quickly place the dyad on the relative risk continuum. The age and weight of the child are largely predictive of the impact of any given herb/medication dose. Another important factor is the maturity of the child’s metabolic and eliminative functions. The newborn is the most vulnerable to chemicals ingested by the mother, being born with immature gut, liver, and kidney function. By about the age of 2 weeks, however, the liver is able to effectively metabolize ingested chemicals competently.15 Kidney clearance capacity increases and becomes fully by 4 to 5 months of age. The adult half-life of a chemical is commonly used to give some measure of whether a drug is likely to accumulate in an infant, even though pediatric half-life is not known for most drugs. Chemicals with half-lives of over 24 hours are of greatest concern as they will accumulate in the infant.12 For neonates with immature metabolic capacity and small body size, serum levels can rise to pharmacologically significant levels more quickly, even with drugs of shorter half-lives. Thus, great caution is required with premature and low birth-weight infants.15

RISKS

Risks of Medications

The American Association of Pediatrics, in 1994, 1997, and 2001, reviewed research and clinical information about drug use in lactation with the latest statement supporting the safety of the use of the vast majority of drugs during breastfeeding. Generally, only the most toxic drugs, such as cancer chemotherapeutics and long half-life radioactive iodine compounds, are absolutely contraindicated. Known adverse events are usually associated with premature or small for gestational weight babies, and such effects often reflect the known side effects in adults. Prediction of risk includes the nature and degree of adverse effects. Certain categories of drugs, such as antidepressants, may be of concern. Although clinical use of many of these substances is widespread, despite the AAP’s concerns, most lack significant adverse effects.12 The safety of antidepressant medications during lactation was discussed in Chapter 16.

Measurement of the degree of milk entry of many types of pharmaceutical substances has led to the realization that few drugs can be expected to cause toxic effects in the infant. Animal lactation studies have been done for some, but not all drugs. Newer prescription drugs often lack studies. Yet, lack of specific lactation studies is not considered reason enough to contraindicate a drug. Indeed, many drugs lack even preliminary study of milk entry in animals or humans. The pharmacokinetic characterization of almost all pharmaceuticals does allow more precise prediction of milk entry, although few fall outside of the 1% to 10% milk entry rule predicted simply from maternal oral ingestion. The clinical evidence for use of most drugs has accumulated through publication of case studies, anecdotes, and experimental study of individuals or very small groups made up of a few mother–baby pairs (often fewer than 10). Typically, milk entry is only characterized for one stage of lactation. Very few drugs have been studied over long-term use, where the child has been exposed to the drug over weeks or months though some drugs are indeed administered in this way. Despite this narrow basis of experimental evidence or quantitative data on drugs during lactation, the increased prescription of medications during lactation has resulted in the documentation of few adverse reactions in children. It is worthy to note here that even drugs such as digoxin, a cardioactive alkaloid with a narrow therapeutic index, is considered compatible with breastfeeding, although close monitoring of mother and baby is necessary to ensure dose limitation.11 As reassuring as this is to lactation experts, it is clear that the actual evidence for safety is quite limited when compared to the evidence for safety in adults. Thus, we know a lot about how a pharmaceutical is metabolized in the mother (pharmacokinetics), allowing tolerably accurate prediction of milk dose, yet have an almost nonexistent experimental base of information regarding actual milk entry or effects in large numbers of infants or over all stages of lactation. Quantification of milk entry and infant serum levels for most drugs is surprisingly limited.

In the Absence of Lactation Studies: Herbs vs. Medications

The powerful nature of pharmaceuticals that inherently generates side effects and drug interactions, as well as their use in complex medical situations results in a relatively high rate of adverse events associated with their use when compared with herbal medicines.16 When comparing the merits of medications vs. herbs, the relatively narrow basis of evidence for safe use of medications during lactation must still be balanced by the fact that most medications are more completely studied, particularly regarding their metabolism and that more elaborate pharmacovigilance systems are in place to monitor their use.17 However, information gained from traditional use cannot be ignored or discarded; traditional information is the basic study material for the scientific discipline of ethnopharmacology after all. Nor can drug data provided by the pharmaceutical industry be entirely trusted to always provide an objective measure of safety. Indeed, the PDR’s statements regarding safety during lactation are singularly useless to guide clinical practice.12,15 Regarding efficacy, the principle of proportionality should not be overlooked.18 Are we talking about the mother having cancer or a cold? How important is efficacy in the risk–benefit analysis? The advantages of an herbal treatment that may not work as quickly or as well compared with a pharmaceutical must be balanced against the need for efficacy.

Herb Risks: Herbs with Pharmacokinetic Information

De Smet and Brouwers provide a systematic review of the state of herbal pharmacokinetics, evaluating the complexities of phytoconstituent bioavailability and pharmacokinetics, and providing a short list of plant constituents where serum levels have been measured.18 The authors advocate pharmacokinetic study of herbs with narrow safety margins or those commonly used for life-threatening disorders, but point out that for herbs with wide safety margins, available in high-quality preparations and used for minor health disorders, the need for such characterization is unnecessary. Yet, bioavailability and serum levels are two measures that are of great utility in assessing herb safety during lactation, if for no other reason than to reassure the doubtful health practitioner. Assessment of herb risk during lactation is hindered by the fact that useful information such as serum levels, half-life, and protein binding are not yet characterized for many phytochemicals. Dose information for any one constituent, usually the “active” constituent, is often available for most controversial or well-researched herbs, and the simple application of the 1% rule to estimate maternal serum levels from oral dose will yield a ballpark estimate of milk entry for the chemical of toxicologic interest. Even if you assume a worse-case scenario and use 10% as the rule, this number is still likely to be very small. Hypericin and soy isoflavones are two examples where serum levels have been measured. Hypericin is a constituent of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) that has been considered active, even though more recent studies indicate a number of other constituents may actually be responsible for the antidepressant activity. In any event, hypericin serum levels have been measured at 8.5 ng/mL following a dose of 900 mg/day of the dried herb.19 This amount represents a very small dose available to diffuse into the milk. The soy isoflavone, genistein, was recently measured in breast milk at concentrations of 0.2 μmol/L in breast milk following ingestion of soy nuts containing a 20 mg of genistein.20 Genistein entry into breast milk appears extremely limited in this study as serum levels were measured at 2.0 μmol/L plasma, representing a 1:10 milk:plasma ratio. This amount is tiny compared to what babies receive when fed soy formula.21

Another class of relatively well-studied herbs is the stimulant laxatives that breastfeeding women are cautioned about for good reason; diarrhea can result from local activity of constituents within the GI tract (compartmental effect). In a study described in Hale, sennosides A and B could not be detected in milk in one study of 20 breastfeeding women using Senokot tablets containing a dose of 8.6 mg sennosides/day.12 Most (15/23) women in the study reported loose stool, of these, two had babies also had loose stools. In another study rhein, an active laxative metabolite of sennosides, was measured in 100 milk samples drawn from 20 women.22 A daily dose of 15 mg sennosides were consumed for 3 days before sampling; 0 to 27 ng/mL was found, with over 90% of the milk samples containing less than 10 ng/mL of rhein. None of the infants had loose stools. However, the senna was combined with the bulking agent, Plantago ovata, which may have slowed or lowered absorption of the laxative constituents into the mothers’ bloodstreams. In contrast to the German Commission E, senna and cascara are considered compatible with breastfeeding; this statement assumes the necessary short-term use of a standardized product in appropriate doses; occasional diarrhea has been noted in neonates but not older children.11

Herb Risk to the Child

Herbs that present a well-documented risk to adults [i.e., those containing aristolochic acid (AA) or toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs)] logically can be expected to present some degree of risk to the breastfeeding child. However, most herbs of commerce lack serious side effects when used appropriately, and thus would not be expected to be able to produce them in infants in the tiny doses of phytoconstituents received in breast milk. Synthetic hormones such as progesterones, estrogens, thyroid replacements, and insulins are compatible with breastfeeding at least infant safety.11 Thus, regarding, the proportional risk posed to the child by the relatively much weaker phytohormones would seem slight. This is not to say that adverse effects cannot occur. Herbs that do have adverse side effects when used appropriately or with narrow therapeutic safety range would be predicted to be much more likely to cause similar problems in the breastfeeding child. These herbs must be used with caution when breastfeeding, even in standardized or OTC forms. Yet, documented infant effects are rarely seen even in the more vulnerable neonates. And, in those instances where the infant has received the plant chemicals through breast milk alone, the adverse effects have been reversible. Appropriate use of herbs by mothers of nursing toddlers is not expected to pose a risk to the child. Still, the mother needs counseling on what appropriate use is, and what potential side effects should be watched for in the child. The strategy of using the medicinal and watching the child for expected side effects is advocated by lactation experts.12,14 If side effects should appear in the infant, the dose is lowered or a different medicinal is used. Obviously, use of questionable herbs during lactation always needs a close look: Alternative approaches that may or may not include the use of other herbs need to be explored or recommended to the mother. A questionable herbal product should not be used by the nursing mother, regardless of the herb. This pragmatic aspect of herb safety cannot be ignored. Education on product selection should be part of any guidance provided to a mother.

The Pregnancy and Lactation Confusion

When reading herbal literature, it is important to determine whether precautions distinguish between pregnancy and lactation. Numerous authors do not make this distinction. To further complicate matters, many authors do not differentiate between self-directed use and supervised use of herbs; thus, it is not at all clear under what use conditions such contraindications are thought necessary.

A prime example of confusing pregnancy and lactation precautions is seen in herbs where many authors contraindicate their use during “pregnancy and lactation due to hormonal influences.”6 For oxytocic or uterotonic herbs, this confounding of pregnancy and lactation is unfortunate as the following discussion shows. Note that “oxytocic” describes an agent capable of causing uterine contractions leading to the delivery of the fetus or placenta. Not all uterotonics are oxytocic, or capable of inducing true labor. “Oxytocin” is the hormone mainly responsible for labor resulting in birth; it is absolutely required for the milk ejection reflex (MER) to occur. Without oxytocin, there is no milk production. (It is worth noting here that women with a healthy pregnancy, who continue to nurse their child do not run an increased risk of premature labor.) Agents that are called oxytocic do not necessarily replace oxytocin, although many probably interact in some way at the oxytocin receptor. A synthetic form (Pitocin) is used to promote labor as well as trigger the MER after birth; it can act at peripheral receptor sites but cannot access the receptor sites within the CNS. At present, there is no information available on plant constituent interactions with oxytocin or its receptors in the brain or at peripheral sites. Although oxytocic herbs are properly contraindicated for self-use during pregnancy, there is a wealth of data on their usefulness in lactation. Galactagogues are herbs used with the intent of increasing milk production. Most herbal galactagogues common in clinical practice in Western countries have some degree of uterotonic or even oxytocin activity. Indeed, many of the hundreds of herbs traditionally used as oxytocics, i.e., speeding labor and delivery of both infant and placenta, are also traditionally used as galactogogues. 23 24 25 Recent lactation research has verified that frequent adequate milk removal is the primary mechanism by which milk production can be increased or maintained.26 Adequate removal of milk immediately increases the rate of milk synthesis in that breast for the next several hours. Oxytocin is needed to remove milk and it is known that increasing the activity of the oxytocin system results in an increased milk flow from the breast, an immediate galactogogue effect. This boost in milk production can stimulate a flagging synthesis rate for a sustained galactogogue effect. Herbs with noted oxytocic effects have been noted to help trigger the MER as well as to increase milk flow. Both these actions can indeed aid lactation. However, a mother needing help with milk production is best served by consulting with a lactation specialist; judicious use of oxytocic herbs can play an important but complementary role.

Maternal Plant Use and Risks to the Infant

A study done in Minnesota examined the dietary habits of experienced breastfeeding mothers to determine what foods might be associated with colic symptoms in infants.27 Researchers found a strong association between the consumption of cruciferous vegetables and the degree of crying and other colic symptoms. Clearly, constituents from the mother’s diet are able to enter breast milk in sufficient quantity to cause the baby discomfort. It is worth noting that vegetables (foods) are consumed in much larger doses than most medicinal plants. No other systematic studies looking at food and adverse reactions in babies have apparently been done, although mothers are routinely told to avoid hot peppers, garlic, and onions by their doctors and others.

Capsaicin, the “hot” constituent in hot peppers, has been noted to cause problems with episodic consumption by the mother, including fussiness, diarrhea, and a red bottom in the baby. However, many mothers who eat hot peppers daily report no such problems. Additionally, infants accustomed to drinking “spicy” milk will readily eat spicy foods when introduced later in the first year. In the Botanical Safety Handbook, the authors classify garlic as an herb to use with caution, and cite references where infant ingestion of garlic resulted in death.10 Clearly, the authors underestimated the dose difference between direct ingestion of a substance, and indirect ingestion of phytochemical constituents through breast milk. Although direct exposure of infants to large quantities of raw garlic may be potentially dangerous, the daily diet of many countries contains medicinal quantities of garlic, yet there are no documented adverse effects of garlic on nursing infants. Garlic is even used as a galactogogue in India. In one human trial, neither efficacy nor harm was demonstrated.25 New lactation studies of garlic have been done, yielding no adverse effects.28 Hale infers it is not known whether garlic constituents enter milk, which overlooks the pioneering work of Julie Mennella et al. who studied the effect of garlic on breastfeeding infants.12 In an earlier study, these authors demonstrated greater interest and longer nursing times in infants whose mothers had ingested a dose of garlic. In a 1993 follow-up study in which mothers ingested garlic daily, the novelty wore off, and the infants went back to their usual nursing patterns. None of the infants suffered adverse effects during these tests. Given the widespread use of garlic as a food, and the existence of studies of garlic and breastfeeding infants, the maternal use of garlic to prevent or treat maternal breast candidiasis (thrush) should be considered a relatively safe and inexpensive alternative to certain medications, such as fluconazole, a powerful antifungal with potential serious adverse effects on the liver.

Allergy and Associated Risks of Direct Feeding on the Baby and Breastfeeding

The risk of allergic reaction to plant chemicals is real and most likely in the first months of life, yet significantly reduced when exposure is restricted through breastfeeding. Not only are the range of plant chemicals reaching the bloodstream reduced but the dose received by the child is very small. Mothers with allergies or atopic and autoimmune diseases will need guidance with allergenic plants, for both her and the baby’s protection. It is also important to determine the father’s allergy history. When possible, initial use of simple rather than combination remedies will assist identification of the culprit if an allergy should occur in a mother or baby. Allergy, atopic, and autoimmune diseases are rampant in modern society, now in this third generation of widespread formula feeding experimentation. Besides being proved as a major preventative of allergenic and atopic disease,15 exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life is also preventative against an enormous range of diseases of both childhood and adulthood;1 direct feeding of substances (whether these are considered food, herbs, or drugs) other than breast milk is clearly an introduced risk.1,29 The young baby’s GI tract is not mature and is still quite “leaky” or permeable to ingested substances, even proteins. Early exposure of the GI tract and flora to foreign substances is thought to set the child up for subtle and frank infections as well as allergy. These effects may have permanent consequences.14 Associated risks go hand in hand with premature direct feeding. It is possible to confuse a baby with bottle or pacifier nipples when used to administer a remedy or drug; replacing breast milk with other fluids will lessen his desire to nurse. (Young babies may only take 2 ounces at a time, an amount easily undermined with frequent “tonic” feeds.) For mothers already experiencing latching or other breastfeeding difficulties, these risks can become considerable, a fact that is not yet recognized in much of herbalist literature. Alternative treatment methods should be sought first. In some instances (e.g., colic), the mother can pass beneficial plant constituents through the milk without risking disruption of baby’s pristine GI tract or throwing her breastfeeding relationship off-track. This wise and much safer method has been long known and is still used by mothers all over the world.

Herbs That Commonly Cause Adverse Effects in Infants: Coffee and Chocolate

Cases of adverse reactions to chemicals, whether drugs or herbs, usually involve newborns. Lawrence and Lawrence state that adverse drug reactions often can be traced to accumulation of the chemical in the infant, leading to adverse effects with increasing serum levels.15 Just about the only herbs that are clearly and consistently able to cause adverse effects seen in infants are CNS-stimulant herbs, most commonly those that contain caffeine and other stimulant xanthine alkaloids: coffee, tea, chocolate, yerba mate, cola, and guarana. Even with its strongly alkaloidal nature, caffeine enters into milk in only tiny amounts. However, it tends to accumulate in the neonate, and can cause fussiness and hyperalertness. This effect is used with premature infants in whom tiny controlled doses of caffeine are given directly to prevent apnea. Despite the fact that mild adverse reactions have been documented in some newborns, caffeine is considered safe for use by breastfeeding mothers. Many mothers can ingest one to two cups of coffee per day without incident, even when breastfeeding neonates, although some babies, like some adults, are acutely sensitive to caffeine and react to any amount of caffeine even as they grow older. Mothers soon find out to what degree coffee, tea, or other caffeine-containing herbs are the cause of their baby’s irritability and adjust their dose accordingly.30

Other Documented Adverse Reactions of Herbs during Breastfeeding

There is a body of literature describing adverse effects when young infants are directly fed herbal preparations or milk substitutes.1,29 Yet, very few cases of adverse reactions are documented involving infants ingesting medicinal phytochemicals through breastfeeding, and those that do exist usually of involve herb ingestion during pregnancy as well. Farnsworth notes one case involving infant death attributed to the mother having used coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) and butterbur (Petasites officinalis) during pregnancy as well as after birth while breastfeeding.16 Both these plants contain hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Without suggesting that the use of such herbs is hazard free during breastfeeding, it is reasonable to suggest that use during pregnancy alone could have produced significant liver damage before any amount was received through the milk. This case involved toxins that cause irreversible liver damage and death in adults, and underscores the need for contraindication of such substances in plant medicine more than that herbs per se are dangerous during breastfeeding. However, it remains entirely possible that the developing fetus as well as the newborn may be particularly susceptible to the toxic forms of pyrrolizidine alkaloids; there are other incidents of children being harmed through direct ingestion of these chemicals. There is no safe dose level established for children and a very stringent one set for adults in Germany. As the liver can sustain damage without immediate symptoms, it remains necessary to encourage nursing mothers to avoid consuming herbs with any amounts of these toxic substances that can cause irreversible adverse effects. Comfrey and borage are commonly used herbs known to contain various amounts of toxic PAs. The other widely recognized dangerous plant toxin is aristolochic acid, which is present in essentially all members of the Aristolochiaceae family. This toxin is associated with permanent and sometimes fatal kidney failure.16,18 The limited elimination capacity of infants may place them at greater risk to this toxin.

The “hairy baby” story has entered the lactation textbooks, even though the original report has subsequently been shown to be incorrect.15,16, 31 32 33 A woman, thinking she was ingesting ginseng throughout pregnancy, was using twice the dose suggested by the label. She developed signs of androgenization during pregnancy, and the baby was born with significant hirsutism and other signs of androgenization. This incident reported ginseng as the likely culprit. A more thorough investigation showed that the package was actually labeled Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus), and that the product was adulterated with the potentially toxic plant, Periploca sepium, although Farnsworth noted that in vitro hormonal studies of the adulterant did not show androgenic activity.16 It was concluded that no likely cause of the hirsutism could be determined. This case has limited application in evaluating the risk of properly prepared herbal medicines during pregnancy or lactation. The “hairy baby story,” however, illustrates the number one deficiency in anecdotal reporting of adverse events involving herbs in medical literature: lack of verified identification of the actual substance consumed.

The first case identified in the literature that involves breastfeeding only was reported by Rosti et al.34 In a letter published in JAMA, the authors tell how two mothers were taking high doses (2 L/day) of an herbal tea with the intention of stimulating lactation, twice the usual dosage of galactogogue teas considered appropriate. Assuming a typical tea, prepared in a standard infusion form, a more typical dose would be 1 L/day total at most. Both of their newborns presented with symptoms that included “reduced growth, poor feeding and sucking, restlessness, emesis, hypotonia, lethargy, and weak cry.” It is not clear how the babies could be both lethargic and restless at the same time. Poor breast milk intake alone could soon cause symptoms involving poor growth, suck and feeding, lethargy, low muscle tone, and a weak cry but would not explain restlessness or emesis. Obviously something was going on with these babies. The tea was reported to contain “a variety of active ingredients” that the authors listed as “licorice, fennel, anise, and goat’s rue.” Symptoms resolved in both infants after the mothers discontinued the herbal teas.34 Although it is common for mothers to ingest teas made from any or all of these ingredients without precipitating a visit to the emergency room, licorice (Glycyrrhiza spp.) and goat’s rue (Galega officinalis) may be worth examining more closely, simply because of their capacities to induce side effects with excessive or prolonged use. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and anise (Pimpinella anisum) both contain trans-anethole, a sweet-tasting compound thought capable of altering CNS activity, at least in high doses. It is quite possible that these babies may have simply been consuming breast milk containing too high a concentration of constituents, too early in the neonatal period, although a distinct lack of other similar adverse events points to other factors. First is the widespread use of such herbs where these mothers come from. In Italy, new mothers as a matter of course go out to buy galactogogue teas in pharmacies, whether they need them or not. Fennel and anise in particular, are favored there, as they have been for thousands of years. Goat’s rue is very commonly used in France, a practice that dates back to antiquity as well. However, plant materials were not positively identified in the article, and adulteration of the presumed plant material is always a possibility, as occurred with the Periploca case. Given that fennel and anise both bear striking resemblance to a number of very toxic relatives (i.e., anise and the potentially toxic star anise have similar flavor), the question of plant identity must be raised. The letter does not indicate whether these women presented independently or were somehow connected. Since the letter’s publication, no further corroborating cases involving any of these herbs have been published. Very little actual knowledge can be gained from such a letter, as the information was not scrutinized by plant or lactation experts and thus is incomplete and unverified.

A report involving the use of dong quai (Angelica sinensis) was published as a letter.35 In this instance, a Chinese-American woman, 3 weeks postpartum, developed an acute onset of headache, weakness, lightheadedness, and vomiting and came to the emergency room for evaluation. In the ER she was found to be hypertensive (195/85). She had no history of hypertension, as verified from her medical record at birth. Blood chemistry and other studies were normal. Earlier that day, she had twice eaten a traditional postpartum soup made by her mother. The soup was reported as being made from Angelica sinensis rhizome that the grandmother had purchased in Malaysia before visiting her daughter. Within 12 hours of arrival at the ER, her blood pressure was once again within normal limits and other symptoms had disappeared. The next day, the baby was evaluated by a pediatrician and found to also have elevated blood pressure, which was treated by withholding breast milk. Within 48 hours, his blood pressure was normal. The authors clearly state that as they could not obtain a sample of the actual soup ingested, they could confirm neither the identity of the actual substance ingested, nor its dose. Use of other herbals or other medicines was denied by the mother. The authors did do the next best thing though, and obtained samples of the same product the mother purchased in Malaysia for analysis by a Chinese medicinal expert (unnamed) who said it was indistinguishable from Angelica sinensis. What is not mentioned in this article is the lack of any other cases in which ingestion of Angelica sinensis has led to high blood pressure. Indeed, the herb is known to be if anything, hypotensive in studies. Thus, the development of hypertension must be considered atypical. This is especially so given that it is a very widespread ancient tradition to use dong quai in postpartum soups for new mothers in Asia. A traditional Chinese medical practitioner in North America has commented that although most ordinary people would know when a new mother is already too “hot” and would not give the soup, it is entirely possible for such a mistake to be made. Further, botanicals imported from China are notorious for being contaminated—it is possible that it was not the herb, per se, but contaminants that, if at all, were associated with this episode.

External Use of Herbs on the Breast and Nipple

Products used to treat thrush or bacterial infections need to be nontoxic and nonallergenic to best ensure safety to the infant, who will be ingesting some share of such products.31 The taste of an external substance can sometimes cause problems. Some babies refuse the breast upon tasting bitter substances and can quickly develop an aversion to the breast. To avoid this, babies must be nursed before external applications and the nipples rinsed before nursing if there are still obvious residues on the nipple. It is possible that many substances in the cream may be absorbed into the breast tissue and thus enter the nearby milk ducts in relatively large amounts; wiping may not avert all potential problems with a questionable product. The use of potentially toxic herbs such as comfrey (which contains PAs) should clearly be seen as being an unnecessary risk to an infant, despite the herb’s excellent healing properties. Safer alternatives, such as Calendula officinalis, should be selected. The use of essential oils on the breast and nipple is in general riskier than use of less-concentrated water-based herb preparations. Yet, tea tree oil is often suggested to treat nipple thrush, a practice that not only lacks evidence of efficacy but may be particularly unwise. First, babies exposed to tea tree oil near their faces and mouths may gag, or in a worst-case scenario, suffer respiratory collapse. This is a well-known phenomenon also known to occur with essential oils of peppermint, camphor, neroli, and cajeput, the last two being from close relatives of tea tree.3 Tea tree oil can be irritating and sensitizing, leading to contact dermatitis, and there are two cases of toxicity associated with its use.3 In one case, an adult developed petechiae and leukocytosis after ingesting about 7 cc of the essential oil; in another, a 17-month-old toddler developed ataxia and drowsiness after swallowing less than 10 cc of the essential oil.12 Taken altogether, tea tree oil should not be used or suggested for nipple thrush and safer alternatives should be sought.

Risks to the Mother

The lactating breast is metabolically extremely active. All components of the milk are brought through the bloodstream and incorporated directly or assembled in the secretory cells. The breast has dermatologically unique areas—the areola and nipple. The nipples mark the boundary between mucous membranes of the internal ducts and external skin of the areola. The skin of the areola is very thin compared with other skin; both areas are extremely sensitive. It is known that breast sensitivity increases during lactation; this facilitates oxytocin release that is triggered in the brain by suckling. There is reason to believe that the lactating breast may be more unusually sensitive to externally applied substances, perhaps because of increased permeability of the skin.25,36 It is known that very sensitive mothers can develop eczema from food residues in their babies’ mouths. The permeability of the breast has not been directly studied, however. Care should be taken for the mother’s safety when applying external products to the breast and nipple.

There are a number of reports of allergic reaction to herbs applied to the nipple, most often in an effort to heal sore nipples. One short communication gives two case histories that involved Roman chamomile Chamaemelum nobile. The herbal cream was applied to sore nipples and resulted in severe exudative eczema on the nipples and the areola.37 In both cases, the mothers used a product marketed for sore nipples. One mother had used the product with her previous child without difficulty. Roman chamomile is much more frequently reported as a cause of allergic reactions than its relatively innocent cousin, German chamomile (Matricaria recutita).

Another case described the use of garlic on the breast, which resulted in skin burns.36 Although the letter did not include this fact, garlic is a known allergen.3 The mother was self-treating a rash on her breast that she thought was “thrush,” in and of itself a likely misdiagnosis. She placed fresh garlic on the rash and left the area covered for 4 days. The baby had access to the nipple and continued to nurse uninterrupted. The mother immediately experienced pain at the site, which continued for the entire time, but she did not remove the garlic plaster. When she presented to the emergency room, she was found to have third-degree burns to the site. Through the whole ordeal, the baby was not deterred from breastfeeding, and suffered no consequences. The authors do a first-rate job of differentiating between the risks and benefits of garlic ingestion vs. external application, clearly saying that this case has nothing to do with internal garlic use and cannot be used as an argument against it. They also do a good job of finding the rather numerous reports of fresh garlic having caused burns when used externally, and correctly point out that the mother’s persistence of use contributed greatly to the event.

Risks and Benefits of Lactation-Modulating Herbs

The risk of herbs during lactation is, in the minds of most practitioners, limited to risk to the infant. Until very recently, both the herbal and pharmaceutical literature restricted consideration of risk to the infant and completely ignored the impact of a medicinal substance on milk supply or fertility.3, 10 11 12 There are some signs of this changing, perhaps related to the widespread successful use of herbal and pharmaceutical lactation modulators.

Hundreds of plants from all cultures are used as galactogogues.25 Only a few of these are known and commonly used in the United States and Europe. Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) (Fig. 18-1), blessed thistle (Carduus marianum), fennel, anise, nettle (Urtica dioica), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), marshmallow (Althea officinalis), and goat’s rue have gained acceptance and see widespread, if mostly undocumented, use by lactation specialists. A well-recognized lactation consultant, Kathleen Huggins, wrote of her extensive use of fenugreek in helping hundreds of women increase milk supply.38 Few side effects were experienced by either mother or baby, although isolated cases of diarrhea or allergic reaction in the mother were noted. Very rarely, an infant may experience diarrhea. Since that report, fenugreek use has become increasingly common and accepted. Combinations of fenugreek and blessed thistle have been recognized to help if taken in sufficient amounts; doses of up to 3 g/day of each have been found efficacious.14 Mothers need to divide the doses and may find that gradual introduction over a few days avoids side effects. Fears of lowering blood sugar, an effect of fenugreek when consumed at 15 to 100 g/day are unfounded at this dose range.39

Formal studies are rare, however. One pilot study of fenugreek showed a positive effect on pumped milk volume in women.40 The most commonly used alternative pharmaceutical, metoclopramide, enters the blood–brain barrier and can cause maternal depression after extended use; domperidone does not enter the CNS and is relatively free of side effects, but because of its orphan status in the United States, it has limited availability.

This is truly a situation in which herbs can be viewed as preferable. Galactagogues are useful only when a true low supply issue exists; their role is secondary to basic lactation techniques to building milk supply. General marketing of herbal galactagogues to breastfeeding women is considered unethical, because it preys upon new mothers’ often unfounded fears of inadequate milk. If a real problem exists, sole reliance on an herb may delay effective assistance without fixing the basic problem. It is critical to point out here that failure to establish a good supply in the early week or two of breastfeeding often results in a permanently reduced supply or weaning. Both herbs and pharmaceuticals can be very helpful in inducing and re-establishing lactation and are sometimes used in combination.14

Risks to Lactation

Herbal risks to milk production are not well discussed in the herbal literature. Most reference texts seem to focus entirely on the toxicity risk to the infant, and are not very consistent in identifying which herbs are traditionally used to increase or decrease milk. For example, the German Commission E entries for fennel make no mention of the herb’s widespread use as a galactogogue, nor does it mention the use of sage for weaning.3 The American Herbal Products Association’s comprehensive review of a large number of herbs is to be commended for considering lactation separately from pregnancy, but likewise neglects to consider an herb’s potential to increase or decrease milk production.10 Feltrow and Avila, although contraindicating just about every other herb in their book, did not contraindicate dill, citing its traditional use as a galactogogue.8 However, the idea that increasing supply is safe, that is always beneficial during breastfeeding, is simply not true. Some mothers may have an overactive milk ejection reflex and produce more milk than their babies can handle; the reasons for this development are unknown. But negative consequences are widely recognized by lactation specialists.30 Herbalist lactation consultant, Mechelle Turner, suggests discontinuing prenatal alfalfa and nettles about 2 weeks before birth, so that their galactogogue influence will not cause or worsen oversupply problems in the early weeks of breastfeeding. Unintentional use of weaning herbs can also cause problems. “Green drinks” that contain parsley juice have been noted to lower supply. Use for oversupply, weaning, or unintentional lowering of milk supply has not been formally studied. These effects are reported in anecdotes gathered by lactation specialists but are in agreement with the traditional lactation use of these herbs. The mechanisms by which herbs may modulate synthesis or supply are far from understood, although for the galactagogues many potential mechanisms, and possibly active constituents, have been summarized in Bingel and Farnsworth’s review of galactogogues.25

Herbs That Influence Prolactin

Endocrine stimulation of the breasts after birth drives the initial production of milk. In this stage, serum prolactin is high with even higher pulses released in response to a nursing session.15 Later, autocrine control mechanisms prevail and each breast independently produces milk in response to milk removal.26 Prolactin levels in later lactation are near normal between nursing sessions but spike after each feeding. Frequent and high prolactin spikes are associated with good milk supply as well as the maintenance of lactation amenorrhea.15 Nonlactating women do not normally show elevated prolactin levels; indeed, hyperprolactinemia is generally seen as a stress response, and is associated with PMS symptoms and some associated infertility states (see Vitex in McKenna et al.).7

Herb influences on prolactin levels during human lactation have not been studied; studies done in this area have used men or nonlactating women, with the exception of chaste berry (Vitex agnus-castus), which has been studied in lactating women.41 Although the studies were done before the discovery of prolactin, and suffer from serious lactation study methodology flaws, the findings consistently indicated a galactogogue effect, in line with the herb’s ancient and traditional use in Germany. Recent in vitro and in vivo animal studies found an antiprolactin and antigalactogogue effect after intraperitoneal injection with rats. 42 43 44 However, the question of dose has been raised. In one tantalizing study, low doses of a chaste berry extract raised prolactin, whereas high doses lowered prolactin in men.45 It is far from clear just what effect chaste berry truly has on human lactation. It is well known, however, that it can be used to induce or re-establish normal ovulation in women with high prolactin levels. Mohr related that those lactating women who were instructed to continued using chaste berry tincture for more than 2 weeks reported an unexpectedly early return of the menstrual cycle.41 This return of the menses and fertility after only a few weeks after birth needs to be seen as a loss of benefit to breastfeeding mothers; decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer is related to the lower estrogen states that are especially prevalent during lactation amenorrhea. On the other hand, other breastfeeding mothers may find this same property of chaste berry of great benefit. Mothers of nursing toddlers may find their fertility is impaired but do not wish to actively wean their children. Chaste berry could restore fertility without the need for stressful mother-led weaning or the use of powerful fertility drugs.

Bugleweed (Lycopus spp.) and prolactin have a complex relationship in which at least some studies have found an antiprolactin effect mediated to some degree through its antithyroid actions.46 Thus, it is generally contraindicated during breastfeeding. Given the many unknowns about bugleweed as well as prolactin, and the necessity of seeking expert medical guidance for situations involving the very complex but critical thyroid gland, general avoidance of this herb during lactation unless under the guidance of a qualified practitioner seems sensible.

HEALTH ISSUES AS SEEN IN THE CULTURAL CONTEXT OF THE BREASTFEEDING WOMAN

Herbal literature has shown little understanding of some health issues pertinent to breastfeeding women. Advice on herbs is generally presented in a vacuum, without consideration of larger cultural issues that are pressuring a breastfeeding mother. These may need to be countered first, to ensure the best protection and support for breastfeeding. Fatigue, depression, anxiety, and weight loss are common health concerns for women in Western cultures. Breastfeeding mothers are like other women and are afflicted with these health concerns. A breastfeeding mother is often isolated and overwhelmed in her role as mother and exclusive source of food for her baby. She often experiences great challenges in taking on her new role as mother, and can easily feel that breastfeeding is to blame for the fatigue, anxiety, and being over her usual weight. Modern Western culture places great importance to a mother getting back to “normal” quickly, even though this is not really possible. The fact is children change everything. Many mothers seek pharmacologic assistance to make these adjustments, and true to our culture’s fondest beliefs, feel that the answer to their problems lies in a pill, whether it is a prescription or an herb capsule. And herein lies the dilemma: Mothers feel they must take “something” to fix problems that are better addressed through finding a network of supporters, sharing in discussions of parenting, breastfeeding with other mothers, or for some seeking counseling. Often, great improvement is experienced once improved communication of her needs is achieved with those closest to her. For example, cognitive therapy is proved to be as helpful as pharmaceutical antidepressants in the treatment of postpartum depression and may be more beneficial in the long term in preventing recurrence with the next child.30

Breastfeeding mothers are terribly sensitive to any information that suggests she is taking a risk in using any medicinal agent yet are culturally conditioned to greatly underestimate the risks inherent in formula use. Thus, she is easily led to wean if it is even hinted that this would be “safer” than using a medicinal or more typically, weaning to use a drug. Although few women wean in order to use an herb (other than tobacco), they may very easily be led to believe that the herbal option is always more dangerous than the pharmaceutical, given the current state of written information. On the other hand, some mothers will not consider anything but the herbal option, thus making it necessary for a rational decision to be made about a particular herb (Box 18-2). It is with these conditions in mind that the following discussion on controversial herbs is offered.

BOX 18-2 Questions to Consider in Assessing Herb Use during Lactation

A Note about Alcohol and Tinctures

Tinctures are sometimes contraindicated during lactation out of concern for the infant receiving some alcohol through the milk. In pregnancy, any amount of alcohol can have negative consequences to the fetus, as exposure comes at a much more sensitive time in development. However, an occasional drink or regular light drinking (one or fewer drinks per day) is considered compatible with breastfeeding.11,30 Heavier drinking (two or more drinks every day) may inhibit the milk ejection reflex.30 Of course, heavy drinking renders the mother unfit for parenting, regardless of how the baby is fed.14 Appropriate use of tinctures, on the other hand, would not be expected to represent this level of alcohol consumption. Tincture use during breastfeeding would seem to be a nonissue, because there is no evidence of harm from a mother enjoying a beer with dinner or a glass of wine or two at a party.30

Unsafe Compared with What? Psychoactive Herbs

Depression and anxiety are two issues that often lead a mother to the doctor’s office. Antidepressants and anxiolytics have commonly been prescribed during lactation, although their use is not entirely accepted given the potential for alteration of brain chemistry in the infant.11 However, some antidepressants enter the milk supply to such a small extent that they cannot be detected in the baby’s serum at all. These drugs are not absolutely contraindicated in lactation because the risks of formula are greater than any observed effects in the baby and untreated depression in the mother also has been shown to impact the baby’s normal development.14 Of course, such agents are not ever to be used lightly and at the lowest dose and shortest time possible. When needed, they should not be withheld or weaning forced.

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is an example of a well-studied herb for which considerable evidence has accumulated suggesting it is efficacious for the treatment of mild to moderate depression.3,7,47 It is expected to be no more of a risk for infant health than any other antidepressant, and perhaps a better risk because it causes fewer side effects in the mother. Few if any effects would be expected in the baby. In a recent study, St. John’s wort has been shown to have an acute negative effect on prolactin levels; within hours of ingestion, prolactin levels drop. However, after 2 weeks extending the same animal model, the herb has been found to increase prolactin levels well above those of the control group, SSRIs have been found to elicit the same drop in prolactin, with levels later returning to baseline.48 However, no study of prolactin response in breastfeeding women exists, and the German Commission E report indicated no known problems with milk supply in this widely used herb.3 If there are no other contraindications to the use of this herb (i.e., concomitant contraindicated medication use), there seems little reason to contraindicate it is a possible therapy for postpartum depression (see Postpartum Depression). There are also a number of other noncontroversial herbal alternatives for many nervous conditions. Valerian, passion flower, and oat straw are just a few of the psychoactive herbs that can be expected to be safe to use during breastfeeding. It is known that anxiolytics such as benzodiazepine can cause sedation in very young infants; necessary use is compatible with breastfeeding when the baby is closely monitored.11 Nervine and sedative herbs are very mild compared with their pharmaceutical counterparts, and the amount of constituents entering breast milk unlikely to be sufficient to sedate a baby. Even though these would be expected to readily enter milk, no adverse events are known. Skullcap has been known to be contaminated with the toxic plant germander, so its use should be limited to reliable sources.

Weight Loss and the Infamous Ephedra Dilemma

Ephedra alkaloids are stimulants that are known to cause overstimulation and sleeplessness in breastfeeding babies.30,49 As well, pseudoephedrine has recently been confirmed to lower milk supply by lowering prolactin levels at least on an acute basis.12 In fact, some practitioners use pseudoephedrine in small doses to lower an overactive milk supply. It is interesting to note that the German Commission E did not contraindicate ephedra in doses of up to 300 mg ephedrine per day during lactation, recognizing its utility for asthma while apparently finding little evidence for risk during lactation when used in a traditional episodic manner.3 Given the stimulant nature of ephedra alkaloids and caffeine, combination products would be expected to yield an additive stimulant effect. Indeed, incidents of serious harm associated with the use of ephedra products typically involve such combination products.

COMMON LACTATION CONCERNS: ENGORGEMENT, CRACKED NIPPLES, MASTITIS, AND INSUFFICIENT BREAST MILK

Herbal treatments for problems associated with breastfeeding can be identified in botanical writings as far back as ancient Egypt. Arabian physician Avicenna describe massaging the breast to improve insufficient milk production, and giving the mother black cumin, carrot, clover, dill, fennel, fenugreek, and leek mixed with fennel water, honey, and clarified butter. Herbs to induce lactation used by seventeenth-century midwives and physicians included aniseed, barley, cumin, dill, fennel, and flax—as well as the traditional well-known treatment—ale. Herbs such as St. John’s wort, poppy oil, and red rose water, usually mixed in some form of oil or fat, were applied directly to the nipples for the treatment of sore, cracked nipples.50 The medieval compendium of women’s medicine, The Trotula, mentions applying plasters of vinegar and clay to the breasts for the pain of breast engorgement and mastitis.

SORE, CRACKED NIPPLES

General Prevention and Treatment

Medical Treatment

The medical treatment of breastfeeding-related nipple problems includes the general strategies listed in the preceding, as well as the addition of antibiotic ointments in the treatment of fungal or bacterial infection. Such preparations are applied after each nursing, for 2 to 5 days, and are considered safe for use during breastfeeding. A lanolin ointment may be recommended in the absence of infection, though some women report sensitivity to lanolin and cannot use it. One report recommended that concentrated vitamin E oil preparations be avoided because they can be toxic to the baby in high doses.51

Herbal Treatment

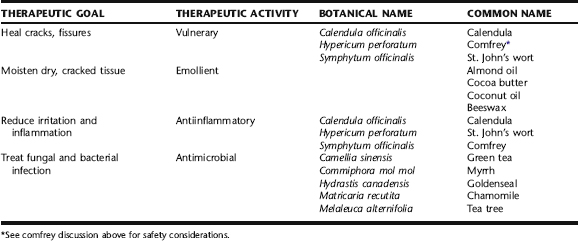

In additional to the general treatment strategies described above, a number of topical herbal preparations are used to assist in the healing of irritated tissue, and as topical anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agents (Table 18-1). Herbal applications for dry, cracked, painful nipples are usually applied as extracted oil or salve, carefully rubbed on the nipple several times daily after nursing. Excess remaining on the nipple can be wiped off prior to subsequent feeding. When there is infection, antimicrobial herbs may be used as tincture diluted in water (1:4), also after feeding, repeated throughout the day.

Discussion of Botanicals

Calendula

Calendula has a long history of use as a vulnerary herb. It is approved by ESCOP and the German Commission E for the treatment of minor inflammations of the skin and mucosa, and as an aid in the healing of minor wounds.52 It is used as an oil extract and in salve for the treatment of inflamed, irritated, sore, or cracked nipples. Hydroethanolic extracts have exhibited antimicrobial and antifungal activity, and may be used as a topical rinse when there is infection.52 There are no data in the scientific literature that supports or refutes the safety of use during lactation. There are no known or expected risks from minimal ingestion by via short-term maternal use on the nipple.

Chamomile

The use of chamomile is supported by the German Commission E and ESCOP for the treatment of skin inflammations and bacterial skin diseases.3,52 There are no expected contraindications or side effects. Rarely, allergic sensitization has occurred from prolonged use of the herb; however, the risk appears very low, especially when Matricaria spp. is used.52,53 The oil of Matricaria has demonstrated activity against Candida albicans at a concentration of 0.7%.52 Several studies evaluating the efficacy of chamomile ointments and hydroethanolic extract in the treatment of topical inflammation and dermatitis have demonstrated improvement, either comparable or superior to cortisone.52 It is frequently included in herbal salves for the nipples, in combination with other herbs discussed in this chapter.

Goldenseal

Goldenseal is positively regarded by herbalists for its efficacy as a topical antimicrobial. There are no human clinical trials studying the antimicrobial effects of goldenseal. Goldenseal extract has shown in vitro and in vivo efficacy in the treatment of Candida infection on the mucous membranes.7 It is commonly used in herbal salve to treat nipple infection and promote tissue healing. Berberine is sometimes listed as contraindicated during lactation. This is based on evidence from animal studies that goldenseal has bilirubin displacing effects and may lead to neonatal jaundice, as well as on the observation that after ingestion of berberine containing herbs, babies with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) developed hemolytic anemia and jaundice.7 After these herbal products were banned for use by the Singapore government, the incidences of neonatal jaundice dropped; yet, they remained high among infants in southern China and Hong Kong, where they were not banned.7 The issue of safety of goldenseal use during lactation remains inconclusive. Blumenthal et al. state that there are no known contraindication during lactation, but its use should be avoided during lactation until further research has been conducted.54 No research has been conducted on the minimal amount that might be ingested by an infant from the use of goldenseal in salve on the mother’s nipples. No adverse effects, nor neonatal jaundice, has been observed or reported from such use in midwifery practice.

Green Tea

A prospective, randomized trial was conducted of 65 primiparas with sore nipples who were breastfeeding after a vaginal delivery at 37 or more weeks gestation, who were 36 hours or less postpartum, and had combined mother–infant care. Participants were assigned randomly to one of six treatment groups with one of three regimens (tea bag compress, water compress, or no compress) randomly assigned to right or left sides. Participants applied the treatments at least four times a day, from Days 1 to 5 postpartum. Tea bag and water compresses were more effective than no treatment, with no statistically significant difference between the two types of compresses. The authors concluded that tea bag compresses are an inexpensive, effective treatment for sore nipples during the early postpartum period.55 Additionally, green tea has demonstrated efficacy against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.56 Water extracts of green tea, or green tea bags, may be applied directly to the nipple. There are no known adverse effects or contraindications to use.

Myrrh

Local anesthetic, antibacterial, and antifungal effects have been reported with use of the sesquiterpene fractions of this herb.57 It is almost always used as an ethanol extract, as it is not highly water soluble; it is also used in powdered form in ointments and directly on weeping, sore tissue. The German Commission E Monographs support its use for the topical treatment of mild inflammations of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa. The diluted tincture (1:4 with water) is dabbed on the affected area two to three times daily, or the mouth is rinsed with 5 to 10 drops of tincture diluted in a glass of water.3 It may be used diluted and applied to the nipples several times daily, and is sometimes used as a rinse in the baby’s mouth if this is the source of the thrush. Hans Schilcher, a German pediatrician, recommends its use as a treatment for oral thrush in Phototherapy in Paediatrics: Handbook for Physicians and Pharmacists.58 There are no known safety contraindications to its use for mother or baby in this manner, with oral doses of up to 3 g/kg showing no major side effects.56

Tea Tree

Current research, presented in a thorough review by Carson et al., supports the use of tea tree oil (TTO) as an antibacterial and antifungal, as well as an anti-inflammatory.59 Limited studies have been done on TTO’s use as an antiviral, but a few trials have indicated possible activity against enveloped and nonenveloped viruses.59 Several studies have demonstrated efficacy against C. albicans; however, to date, no clinical trials have been done. A rat model of vaginal candidiasis supports the use of TTO for VVC.59 The mechanisms of antimicrobial action are similar for bacteria and fungi and appear to involve cell membrane disruption with increased permeability to sodium-chloride and loss of intracellular material, inhibition of glucose-dependent respiration, mitochondrial membrane disruption, and inability to maintain homeostasis. 60 61 62 63 Perhaps what has attracted the most interest in this herb is that it has demonstrated activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Further, its use in Australia since the 1920s has not led to the development of resistant strains of microorganisms, nor have studies that have attempted to induce resistance, with the exception of one case of induced in vitro resistance in Staphylococcus aureus.64,65 Tea tree oil applied directly to the nipple can be caustic and irritating, and should only be used highly diluted (1:10 with a carrier oil such as almond oil). Further, there is no established safe dose of this for babies. There are several reported cases of ataxia and drowsiness in young children who consumed 10 mL or less of the oil; therefore, TTO is not recommended for use as an oral rinse for babies with thrush, and if it is used to treat nipple thrush, the nipple should be rinsed off thoroughly before nursing.56

Breast Engorgement

National surveys in the United Kingdom have shown that painful breasts are the second most common reason for giving up breastfeeding in the first 2 weeks postpartum.66 One factor contributing to pain is breast engorgement. Views differ as to how engorgement arises, although restrictive feeding patterns may be contributory.66 Engorgement refers to swelling of the breast associated with breastfeeding. Engorgement is classified as early or late in onset, depending on when in the postpartum period it arises. Early engorgement occurs because of edema, inflammation, and accumulated milk, whereas late engorgement is caused by accumulated milk only. Early engorgement typically occurs between 24 and 72 hours postpartum but may occur any time in the first postpartum week. Even a significant amount of engorgement may occur following birth, with a sense of fullness, warmth, and heaviness in the breasts, a normal physiologic change owing to an increase in the vascular supply.66 In some women, milk production exceeds the baby’s demand, and excess milk builds up, leading to distention of the alveolar sacs, and consequently hot, tender, swollen, and painful breasts. Edema may occur, if untreated, because of pressure of the surrounding tissue on lymph nodes, preventing their draining.

General Prevention and Treatment

Medical Treatment

In addition to the practical strategies described in the preceding, analgesics may be considered for severe pain. The American Academy of Pediatrics considers acetaminophen and ibuprofen safe and effective for pain relief during breastfeeding.68 Serrapeptase, a proteolytic enzyme product, is commonly used throughout Europe for the treatment of inflammatory and traumatic swelling, as an alternative to salicylates, ibuprofen, and other NSAIDs. Serrapeptase has been used in the treatment of fibrocystic breast disease and breast engorgement. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 70 patients complaining of breast engorgement were randomly divided into a treatment group and a placebo group. Serrapeptase was superior to placebo in improving breast pain, breast swelling, and induration, with 85.7% of the patients receiving serrapeptase reporting moderate to marked improvement.69 A review by the Cochrane database found that serrapeptase (Danzen) and bromelain/trypsin complex (OR 8.02, 95% CI 2.8–23.3) improved symptoms of engorgement, compared with placebo. Serrapeptase is available as an over-the-counter nutritional supplement. No data are available regarding its entry into milk or potential side effects in breastfeeding infants.66

Herbal Treatment

Midwives routinely use the common sense strategies described under General Prevention and Treatment. These are usually adequate to prevent or relieve engorgement. If there is mastitis, botanical treatment strategies are added (see the following). A popular folk remedy for the treatment of breast engorgement is the application of cabbage leaves to the swollen breasts. Fresh, refrigerated leaves are slightly crushed, for example, by rolling under a rolling pin, and are applied to the breast to draw out heat and inflammation. The leaves are left on until they become warm, and then are changed. This is repeated several times daily. According to a Cochrane review, cabbage leaves were no more effective than the use of gel packs for relieving discomfort.66

PLUGGED DUCTS AND MASTITIS

Milk ducts can become plugged, distended, inflamed, and tender owing to localized milk stasis. In mastitis, the plugged ducts are accompanied by infection. The differential diagnosis between plugged ducts and mastitis is the absence of signs of systemic infection including fever, local redness, and myalgia. Plugged ducts are most often easily treated by applying heat and gently expressing the blocked milk. Rarely, a galactocele may form in which the milk congeals into a thick consistency and requires aspiration. Factors contributing to plugged ducts are similar to those for breast engorgement (see the preceding), and similar prevention strategies should be employed, including ensuring proper position of the baby on the nipple during feedings, and using gentle massage and heat to facilitate milk release from the duct. It may take several days to completely empty the duct and for residual soreness to resolve.

Mastitis is a breast infection affecting at least 1% to 3% of lactating women. Symptoms include a hard, tender, inflamed area of one breast, accompanied by fever which can become quite elevated (as high as 104° F). Women almost invariably complain of chills, achiness, and malaise. Infection is commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Escherichia coli. Fungal mastitis may also occur, typically owing to Candida infection, with sharp, shooting pains a common symptom. Risk factors for developing mastitis include cracked nipples or nipple sores, recent antibiotic use, use of antifungal nipple preparations within 3 weeks, and use of a manual breast pump. Diabetes, steroid use, and oral contraceptive use also increase the risk of Candida mastitis. Women with mastitis with a previous child have an increased likelihood of a repeated episode.70 Breast abscess may occur in 5% to 11% of women with mastitis.71 Relapse is common with mastitis; therefore, care must be taken to treat completely, and ensure adequate rest and nutrition, as well as avoiding contributing factors (e.g., tight brassieres, improper emptying of the breast).

General Treatment

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment of mastitis includes regular complete emptying of the affected breast (breastfeeding, pumping), bed rest, pain management with anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., ibuprofen), and a 10- to 14-day course of antibiotics. The World Health Organization protocol suggests that breast milk be cultured and antibiotics prescribed according to sensitivity testing in cases in which there is no response to antibiotics in 48 hours, the infection is hospital acquired, there is relapse, or the case is severe.72 Nystatin treatment is given to the mother and infant for Candida mastitis. Should abscess occur, draining may be accomplished with needle aspiration.73 Women with unresponsive and intractable mastitis should also have other causes ruled out, such as breast cancer.

Herbal Treatment

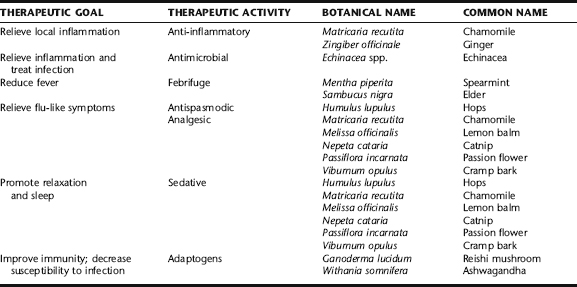

Herbal treatment for mastitis consists of herbs to treat local inflammation and infection, and those to relieve systemic symptoms associated with fever such as myalgia and chills (Table 18-2). Improvements are usually seen within 12 to 24 hours, and complete recovery usually occurs in 48 hours. Should symptoms worsen, abscesses form, or treatment not lead to adequate results within 72 hours, medical treatment should be sought. Following the general instructions for plugged ducts and mastitis (see the preceding), along with herbal treatment, is essential for good results. As mastitis commonly recurs, general recommendations such as consuming adequate fluids, avoiding tight-fitting bras, and regularly emptying the breasts by breastfeeding are recommended beyond the duration of the infection as a general practice. Women with recurrent mastitis should be evaluated for adequate nutritional intake, particularly iron, protein, vitamin C, and zinc, because deficiencies of these nutrients can lead to susceptibility to infection. Adaptogens should be considered to enhance immunity, particularly if there is fatigue accompanying relapsing mastitis. Herbs to consider while breastfeeding include ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) and reishi mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum). Additional adaptogens were discussed in Chapter 6.

INSUFFICIENT BREAST MILK

General Treatment

Medical Treatment

In addition to the general strategies described in the preceding, medical intervention includes the use of dopamine antagonists as galactagogues to augment lactation. Most exert their pharmacologic effects through interactions with dopamine receptors, resulting in increased prolactin levels and thereby augmenting milk supply. Metoclopramide (Reglan) is the preferred pharmaceutical agent because of its documented record of efficacy and safety in women and infants. Domperidone crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the breast milk to a lesser extent than metoclopramide, decreasing the risk of toxicity to both mother and infant possibly making it an attractive alternative. Traditional antipsychotics, sulpiride and chlorpromazine, have been evaluated, but adverse events limit their use. Human growth hormone, thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH), and oxytocin have also been studied. There are insufficient studies on the safety and efficacy of growth hormone in the infant, TRH is not commonly used for this purpose, and although it was highly effective at increasing milk production in limited studies, oxytocin is no longer available on the market.77

Herbal Treatment

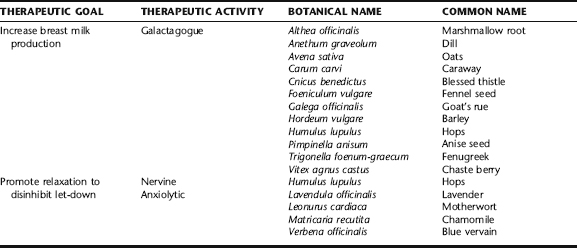

The use of galactagogues to enhance milk production and relaxing herbs (nervines, anxiolytics) to promote let-down is as old as the proverbial hills, with traditional herbals and “recipe” books nearly ubiquitously containing recipes for these purposes (Box 18-3). The use of aromatic spices such as aniseed, caraway, cinnamon, dill, fennel, and fenugreek remains popular today.56 Other commonly used galactagogues include chaste berry, barley, goat’s rue, blessed thistle, oats, hops, nettle leaf, slippery elm bark, and marshmallow root, many of which are discussed in the following. Nervines and anxiolytics are important adjuncts to improving breast milk production and delivery to the baby. Specific herbs for this purpose are listed in Table 18-3; readers are directed to Plant Profiles for detailed discussions of their use and safety during lactation.

Discussion of Botanicals

Anise Seed, Fennel Seed, Caraway, and Dill