Chapter 5 Breast Ultrasound

Technical Considerations

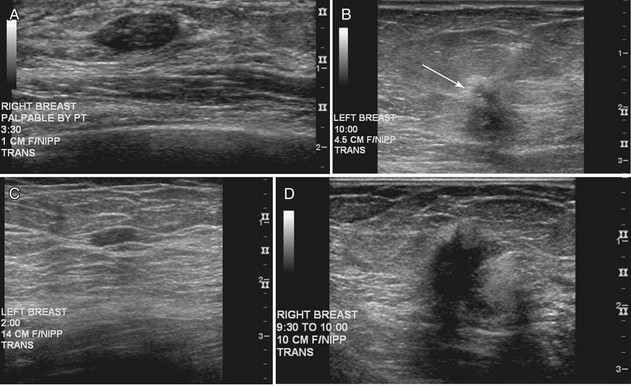

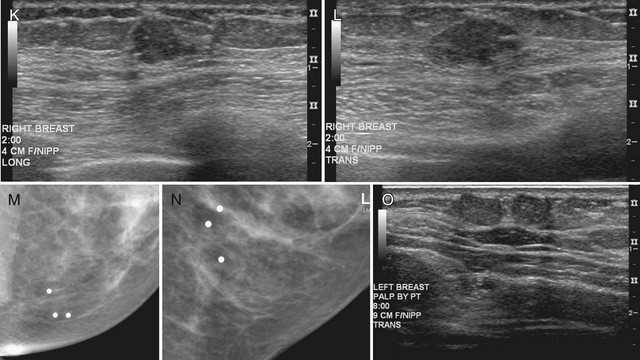

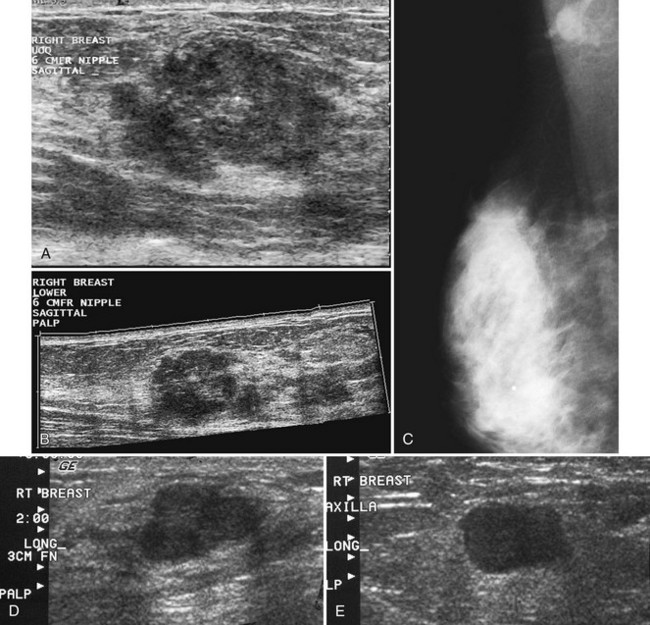

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has made specific recommendations for ultrasound labeling. The sonographer labels each finding according to its location in right or left breast, quadrant or clock position, scan plane (radial or antiradial, longitudinal or transverse), and number of centimeters from the nipple, along with the sonographer’s initials (Box 5-1). The sonographer takes images of the mass with and without measuring calipers. Any other pertinent clinical information, such as whether the lesion is palpable, may also be helpful to note.

Normal Sonographic Breast Anatomy

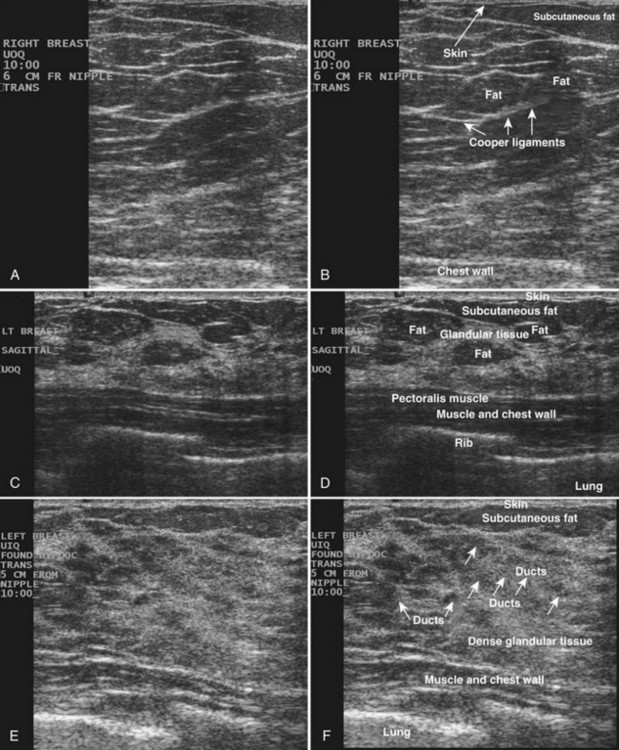

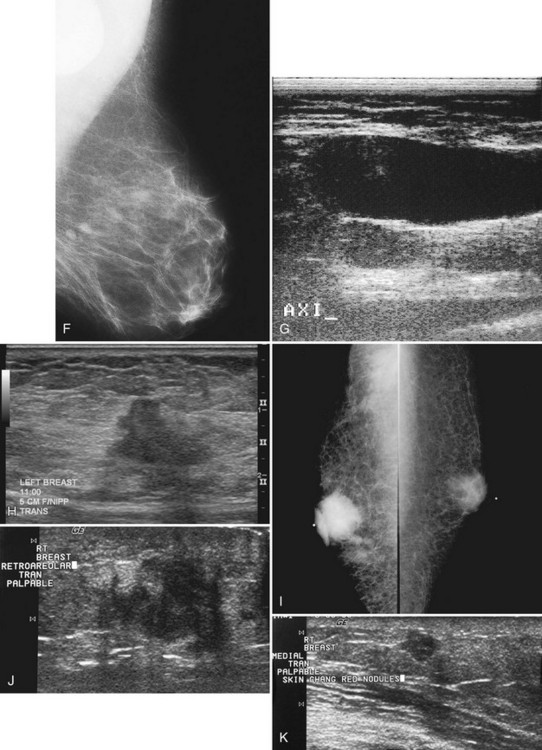

The breast is composed of fibrous connective tissue (Cooper ligaments) arranged in a honeycomb-like structure surrounding the breast ducts and fat (Fig. 5-1A and B). The proportion of supporting stroma to glandular tissue varies widely in the normal population and depends on the patient’s age, parity, and hormonal status. In young women, breast tissue is composed of mostly dense fibroglandular tissue. In later years, dense tissue involutes into fat in varying degrees, producing a mixed fatty and dense breast or an all-fatty breast (see Fig. 5-1C to F).

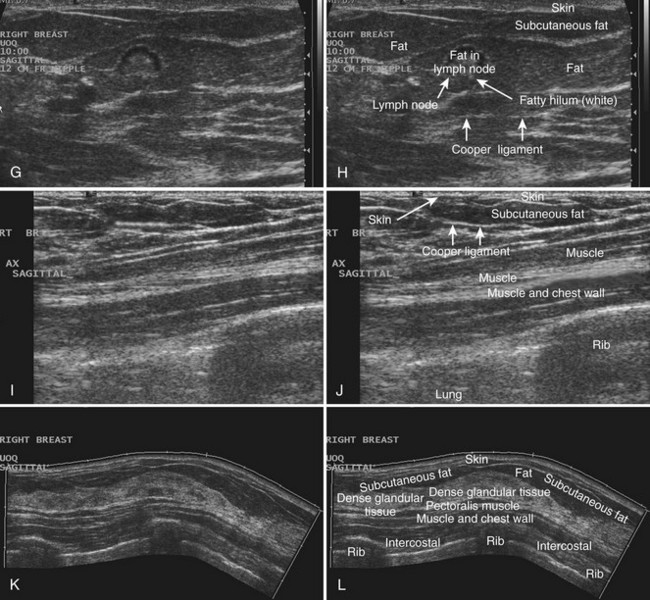

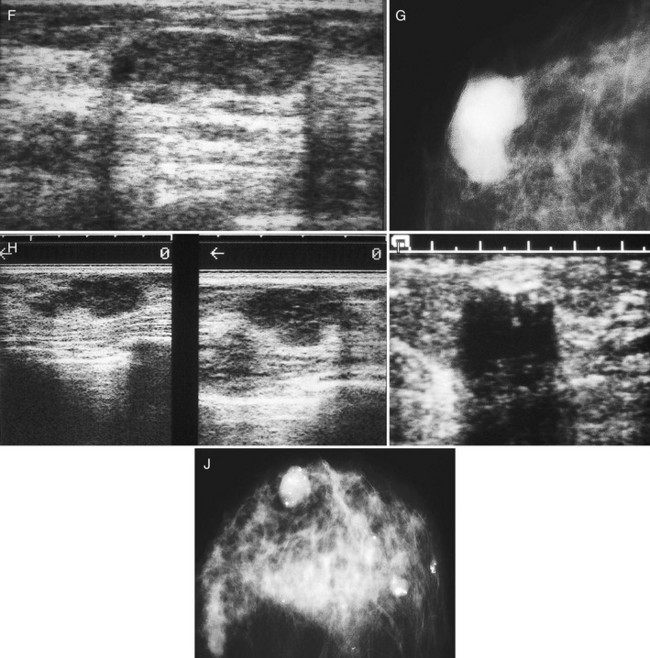

Breast tissues are either echogenic (white) or hypoechoic (black) on ultrasound. The skin is an echogenic line immediately under the transducer in the near field. It is normally about 2 to 3 mm thick and has a hypoechoic layer of dark subcutaneous fat immediately beneath it (Box 5-2). Unlike echogenic or white-appearing fat around the superior mesenteric artery in the abdomen, fat in the breast appears dark or hypoechoic. The only exception to hypoechoic fat in the breast is the echogenic fat in the middle of a lymph node. The normal lymph node is an oval, well-circumscribed mass with a hypoechoic cortex and fatty echogenic hilum, often seen in the upper outer quadrant and axilla, and often near an artery (see Fig. 5-1G and H).

Box 5-2 Normal Ultrasound Appearance of Breast Tissue*

Skin: 2- to 3-mm echogenic superficial line

Fat: hypoechoic (exception: fatty hilum in lymph nodes)

Breast ducts: hypoechoic tubular structures, oval in cross-section

Nipple: hypoechoic, can shadow intensely

Cooper ligaments: thin echogenic lines

Ribs: hypoechoic, round periodic structures at the chest wall

Breast glandular tissue and connective tissue are echogenic or white. Connective tissue has the highest acoustic impedance, fat has the lowest, and glandular parenchyma is of intermediate echogenicity. The Cooper ligaments are thin, sharply defined linear structures that support the surrounding fat and glandular elements (see Fig. 5-1I and J). Cooper ligaments in a fatty breast look like thin, white, gently curving lines surrounding hypoechoic fat. Normally, Cooper ligaments are thin and sharply demarcated. In breast edema, the fat becomes gray and the normally sharp Cooper ligaments become blurred.

The pectoralis muscle is a hypoechoic structure of varying thickness that contains thin lines of supporting stroma coursing along its long axis at the chest wall near the bottom of the image. The pectoralis muscle abuts the intercostal muscles and fascia of the chest wall (see Fig. 5-1K and L). Ribs in between the intercostal muscles are round or oval in cross-section, shadow intensely, and are seen at regular intervals along the chest wall. High-resolution transducers may display calcifications in the anterior portions of the cartilaginous elements of the ribs. Newcomers to breast ultrasound may mistake the ribs for masses, but their periodicity along the chest wall and the fact that one can palpate the ribs along their course will help prevent newcomers from making this mistake.

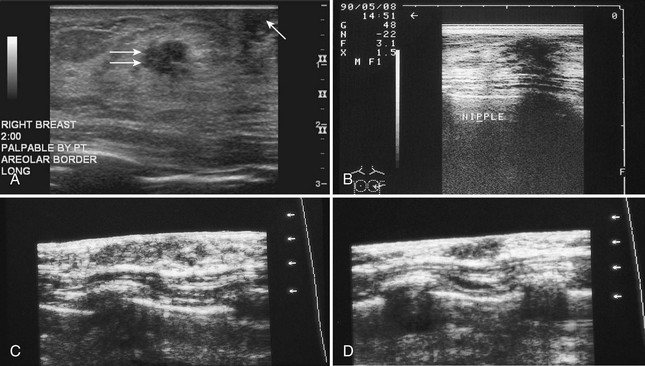

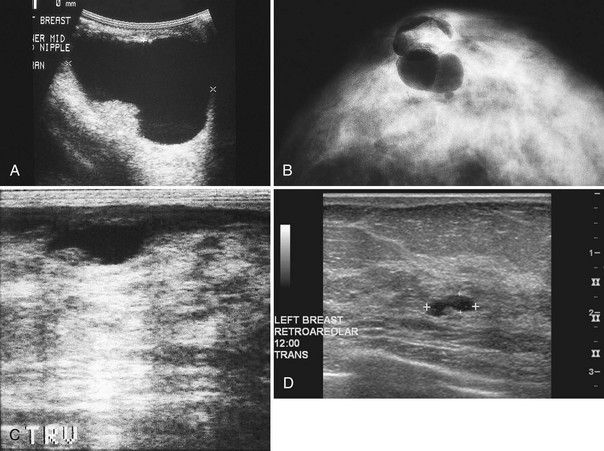

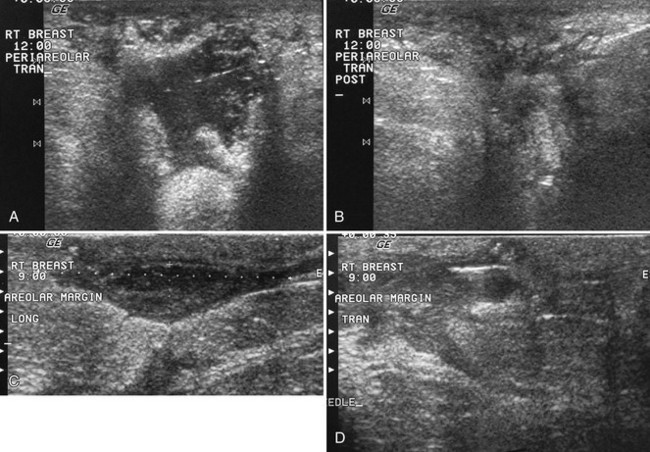

The nipple is a hypoechoic structure at the skin surface that occasionally produces an intense acoustic shadow as a result of the dense connective tissue within it (Fig. 5-2A and B). Because of the presence of retroareolar ducts and blood vessels, there may be marked vascularity in the retroareolar region on color or power Doppler imaging. Newcomers to breast ultrasound may mistake the nipple for a breast mass because of its hypoechoic appearance, shadowing, and the intense vascularity beneath it. However, knowledge of the shadowing, vascularity, and the ability to correlate the mass with the nipple on physical examination will help prevent newcomers from making this mistake.

In children, the breast bud that develops into the adult breast is right underneath the nipple. The breast bud may produce an asymmetric lump under the nipple that may be mistaken for a mass rather than a normal developing structure (see Fig. 5-2C and D). This normal structure should be left alone because surgical removal of the breast bud results in no breast formation on the ipsilateral side.

Ultrasound Evaluation of Mammographically Detected Findings

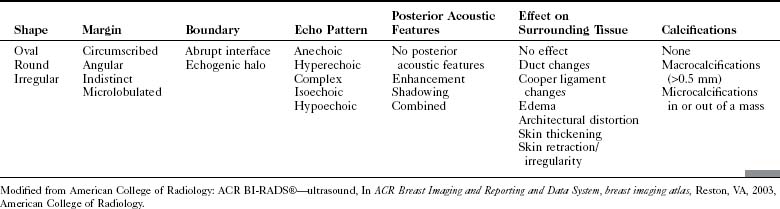

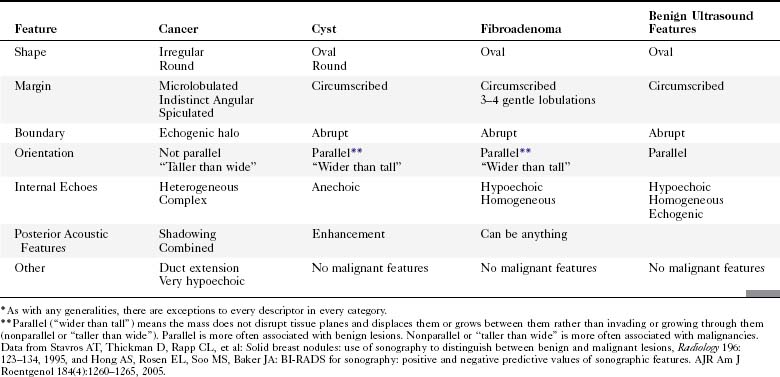

The ACR Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) committee developed an ultrasound lexicon to provide descriptors for findings seen by ultrasound and recommended specific descriptors for breast masses (Table 5-1). Use of the words in the ACR BI-RADS® lexicon helps clarify one’s impression of the finding, improves communication between the radiologist and referring physician, and may trigger specific patient managements. This is because specific ultrasound features described by the lexicon suggest either benign masses or cancer. Although there is some overlap in benign versus malignant ultrasound features, the radiologist can use the lexicon to be reminded of what features should be searched for on the image (Table 5-2).

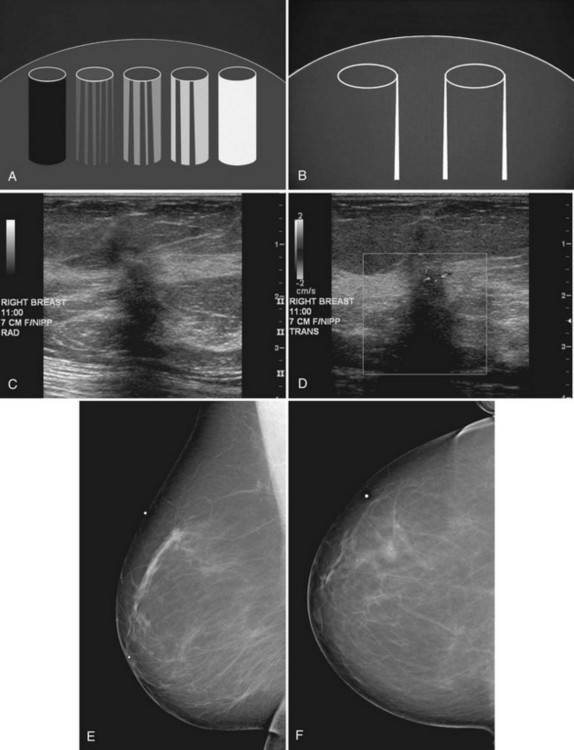

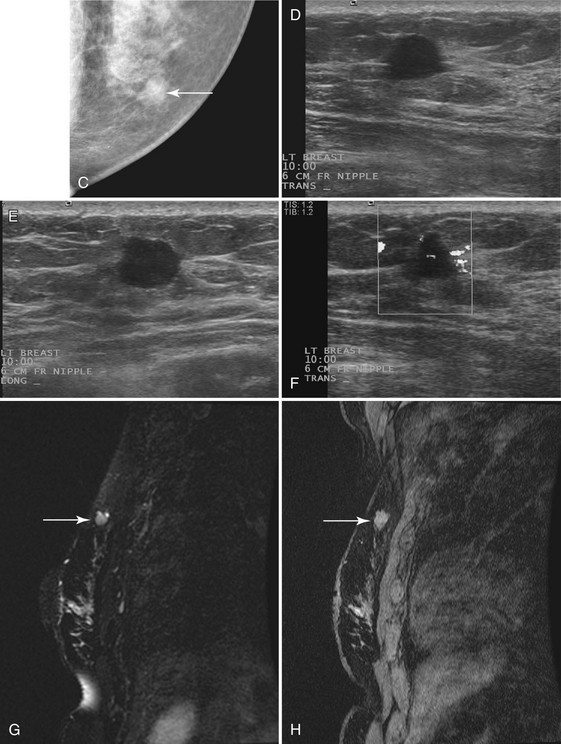

The BI-RADS® ultrasound lexicon descriptors for breast masses and their effect on the surrounding breast tissue are illustrated in Figures 5-3 to 5-6. Mass shapes are reported as oval, round, or irregular. Mass margins are circumscribed, angular, indistinct, microlobulated, or spiculated. The internal echo pattern is described as anechoic (all black inside), hyperechoic (white), complex (mixed black and white), isoechoic (equal), or hypoechoic (dark). Posterior acoustic features are described as no posterior acoustic features, enhancement (white), shadowing (dark), or a combined pattern. The boundary between the mass and the surrounding tissue is described as having an abrupt interface or as containing an echogenic halo (a white blurry band surrounding the mass). Calcifications are described as no calcifications, macrocalcifications (>0.5 mm), microcalcifications within the mass, or microcalcifications outside the mass. Effects of the mass on surrounding breast tissue are described using the terms no effect, duct changes, changes in Cooper ligaments, edema, architectural distortion, skin thickening, skin retraction, and skin irregularity.

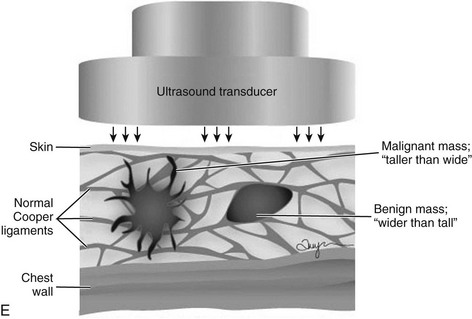

The terms parallel or not parallel relate to tumor growth patterns with respect to normal tissue planes. They are important because they indicate if the mass is growing along or in between tissue planes versus growing through them. A parallel growth pattern indicates a benign finding (wider than tall, as described by Stavros and colleagues) because it indicates a growth pattern along tissue planes. Not parallel or taller than wide indicates that the mass is growing through the normal tissue planes, which is not normal and indicates cancer (see Fig. 5-6E).

Finally, the ultrasound BI-RADS® lexicon suggests standard reporting for masses, as in Box 5-3.

Box 5-3 Ultrasound Mass Reporting

Breast Cysts, Intracystic Tumors, and Cystic-Appearing Masses

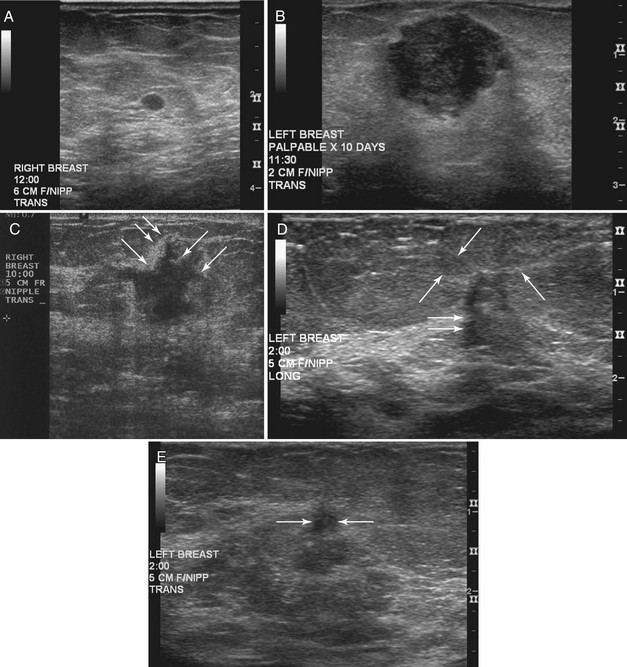

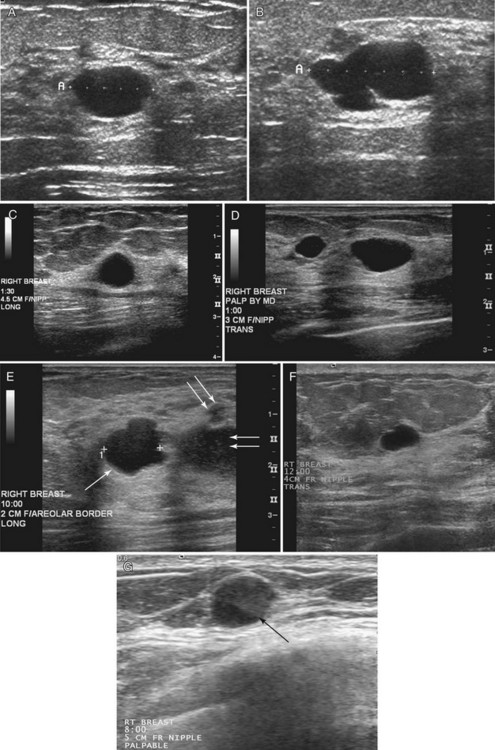

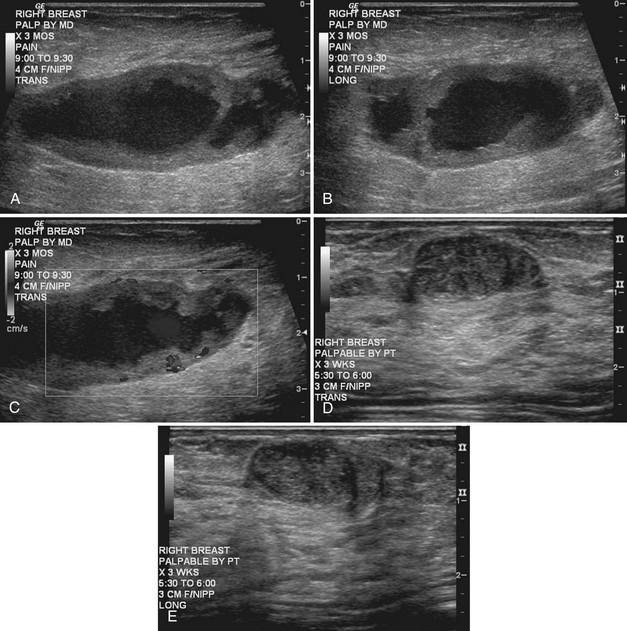

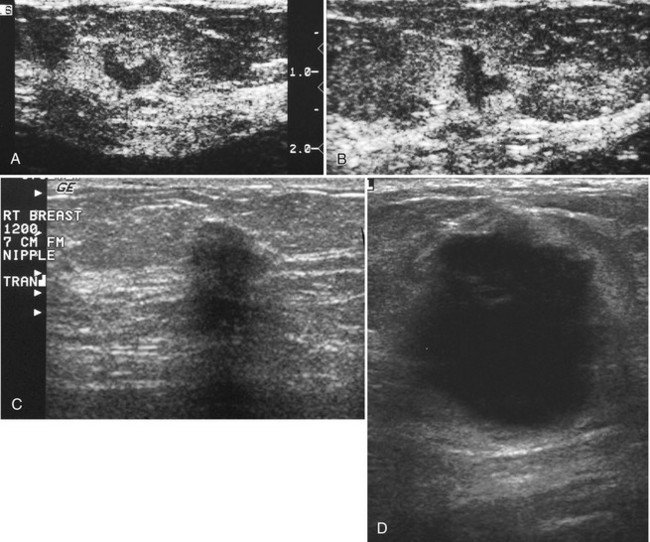

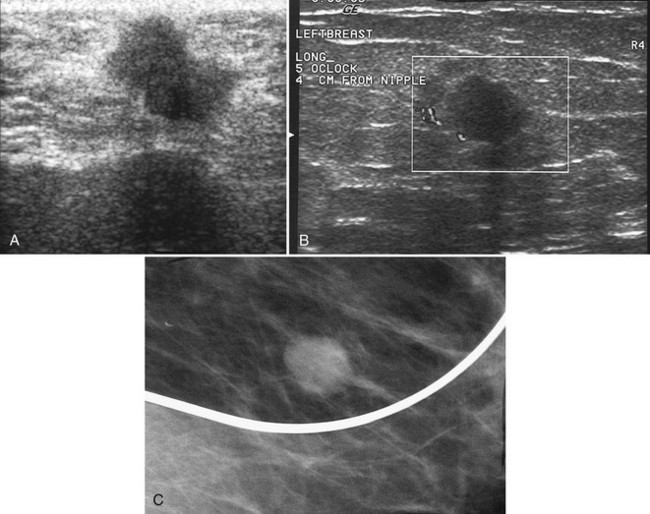

Strict ultrasound criteria for a simple cyst include a mass with well-circumscribed margins, sharp imperceptible anterior and posterior walls, a round or oval contour, absence of internal echoes, and posterior acoustic enhancement (Box 5-4 and Fig. 5-7A). Cysts may be single or multiple, gathered into small clusters, or contain thin septations (see Fig. 5-7B to D). Cysts are not malignant or premalignant, but examination of them is important because they may cause lumps that mimic round cancer on physical examination or mammography. When palpable, a cyst is a smooth, mobile mass on physical examination. Occasionally cysts appear as a visible mass if the patient is supine and the cyst is large. Cysts may be painful and may wax and wane with the patient’s menstrual cycle. If a mass is proven to be a cyst by ultrasound, the patient can be monitored by screening mammography because cysts are not cancer. Symptomatic cysts that are painful or cause a lump that disturbs the patient can be treated by aspiration. Cysts may be simple or “complicated,” meaning that the cyst contains sloughed debris. These complicated cysts contain material within them rather than being anechoic. Some complicated cysts require aspiration to confirm that they are cysts rather than solid masses (see Fig. 5-7E).

Deeply located cysts may not show enhanced through-sound transmission because of their location close to the chest wall, and lateral cyst walls may be obscured by refractive shadows (see Fig. 5-7F). These problems may be resolved by repositioning the patient or the transducer to scan from a different angle. This permits visualization of distal acoustic enhancement or eliminates the refractive shadows obscuring the sharp cyst walls. Acorn cysts contain a fluid/fluid level, with the dark dependent portion of the cyst representing clear fluid (the acorn) and the lighter top representing layering fluid above it (the acorn cap) (see Fig. 5-7G). Changing the patient’s position may cause the layer to move dependently, clinching the diagnosis of an acorn cyst.

The internal characteristics of cysts must be analyzed to exclude mural masses or irregular thick walls, which indicate complex masses. Complex masses contain cystic and solid components; intracystic tumors and necrotic neoplasms are in the differential diagnosis. Complex masses are different from complicated cysts, which contain debris. Complex masses might be cancer, but complicated cysts are benign (Table 5-3 and Boxes 5-5 and 5-6).

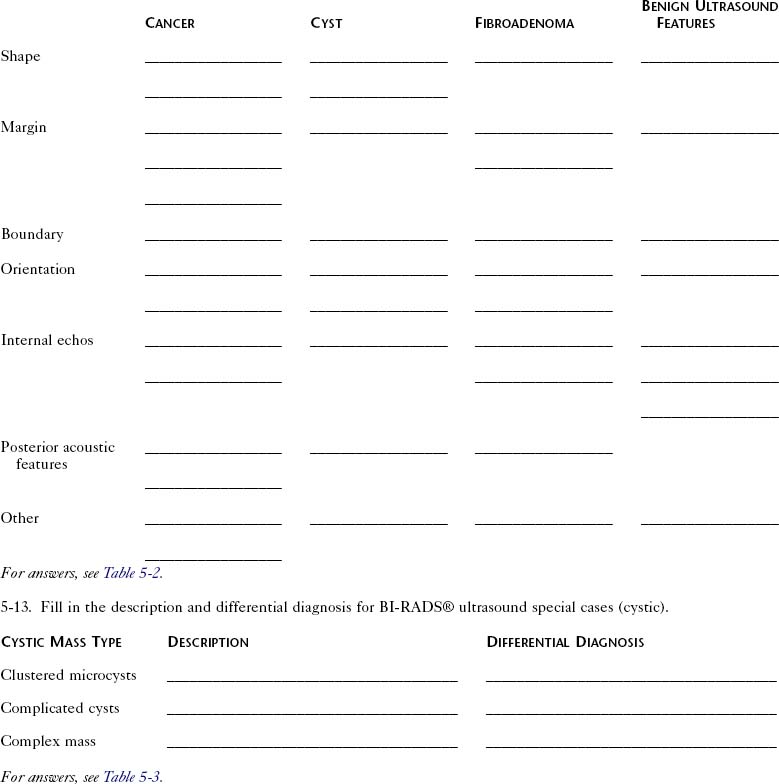

| Cystic Mass Type | Description | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Clustered microcysts |

Modified from American College of Radiology: ACR BI-RADS®—ultrasound, In ACR Breast Imaging and Reporting and Data System, breast imaging atlas, Reston, VA, 2003, American College of Radiology.

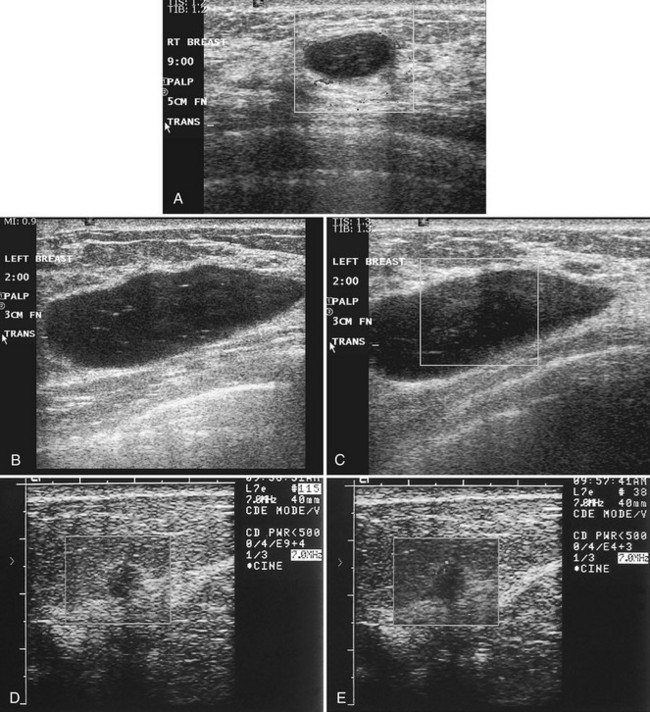

Real-time ultrasound imaging can help distinguish speckle artifact from debris in cyst fluid from a solid mass. Real-time ultrasound can show particulate matter slowly moving inside the cyst. On real-time imaging, the debris causes speckle artifact, which swirls in the cyst like fake snow in a snow globe (Fig. 5-8A to C). Placing the patient in the decubitus position can cause a difference in the sedimentation pattern in the complicated cyst, but not always. Color Doppler or power Doppler ultrasound can detect movement of particulate matter within complicated breast cysts or blood vessels in solid masses (see Fig. 5-8D and E). Doppler imaging will show no blood vessels in breast cysts. Unfortunately, the absence of blood flow in a mass is not diagnostic of a cyst because Doppler imaging does not always detect blood flow in solid masses or even in cancers.

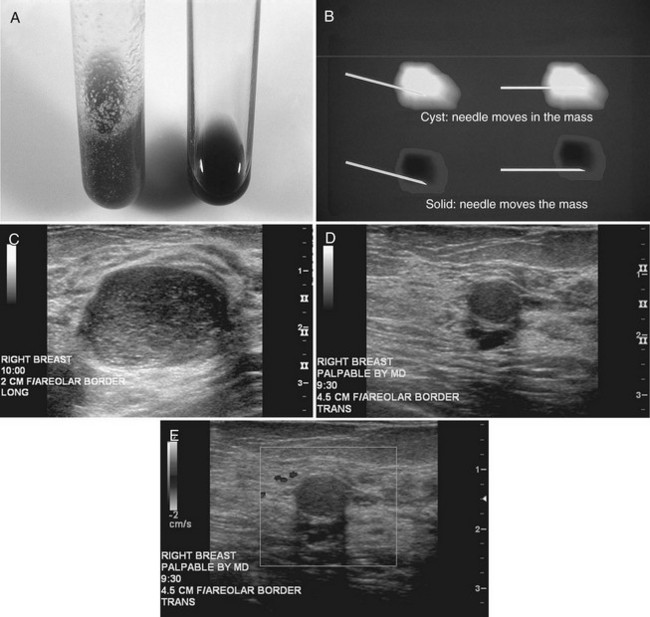

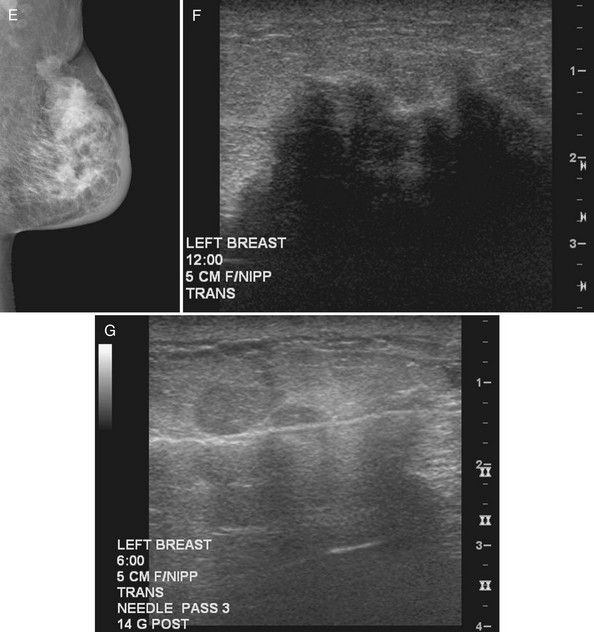

Differentiation of complicated cysts from benign or malignant cystic masses can be tricky (see Table 5-3). Some cysts contain true internal echoes as a result of thick tenacious fluid or hemorrhage from previous aspirations. Some cysts have thick walls as a result of inflammation from cyst fluid leaking into the surrounding tissues. In cases in which all the sonographic criteria of a simple cyst have not been met, fine-needle aspiration may obviate the need for core needle biopsy or surgical biopsy. Once the needle is within the mass, the presence of cyst fluid rather than solid tissue can be confirmed by moving the needle, as suggested by Stavros and colleagues (Fig. 5-9). Cysts that do not fulfill all criteria for simple cysts, in the right clinical setting, require aspiration (see Fig. 5-9C to E). Cyst fluid should be sent for cytologic analysis if it is bloody, if there is an intracystic mass on ultrasound or pneumocystography, or if the patient has had prior intracystic carcinoma. Clear cyst fluid can be discarded if there are no clinical factors that would require cytologic examination.

On the other hand, complex cystic masses (i.e., fluid-filled masses with thick walls or mural projections) require biopsy to exclude the rare intracystic papilloma, intracystic carcinoma, phyllodes tumor with a marked cystic component, or solid cancers with central necrosis. Other complex masses include hematoma, abscess, galactocele, and seroma; management of these masses is based on their appearance and the clinical situation (Fig. 5-10).

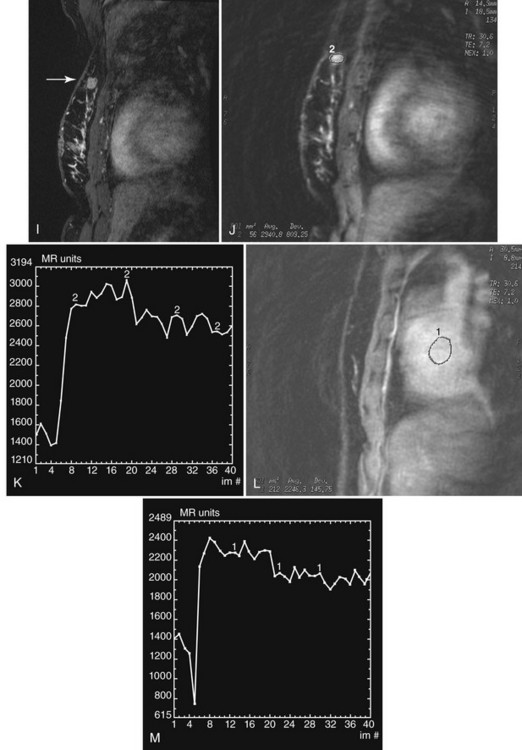

Intracystic carcinomas are a rare subgroup of tumors that arise from the walls of a cyst; they represent 0.5% to 1.3% of all breast cancers (Fig. 5-11A). These tumors have a better prognosis than other malignant breast neoplasms do. On ultrasound, intracystic carcinomas often appear as solid mural excrescences projecting into the cyst fluid. Differentiation of intracystic carcinoma from benign intracystic papilloma is not possible, and surgical biopsy is thus necessary. The finding of a mural nodule within a cyst has the differential of an intracystic carcinoma, papilloma, a cyst with debris, and reverberations in a simple cyst produced by high gain settings (see Fig. 5-11B to D). Color or power Doppler imaging may be helpful if a blood vessel can be identified in the intracystic mass.

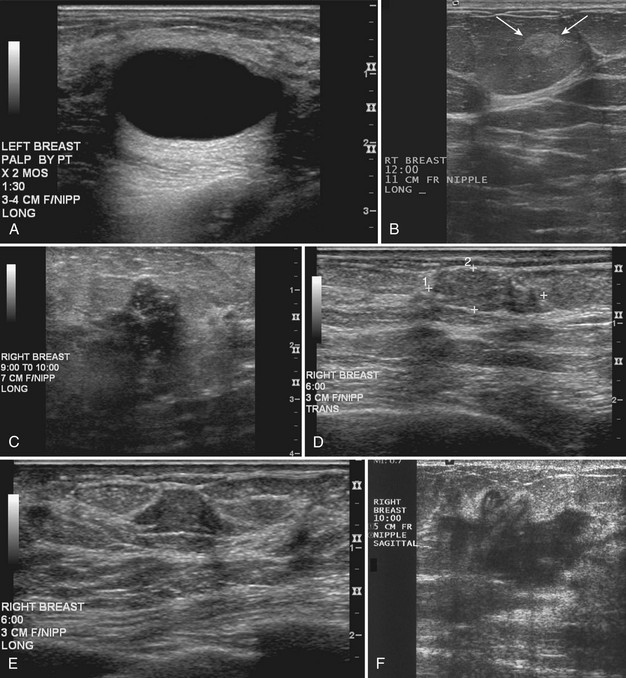

Benign Solid Masses: Fibroadenoma and Fatty Pseudolesions

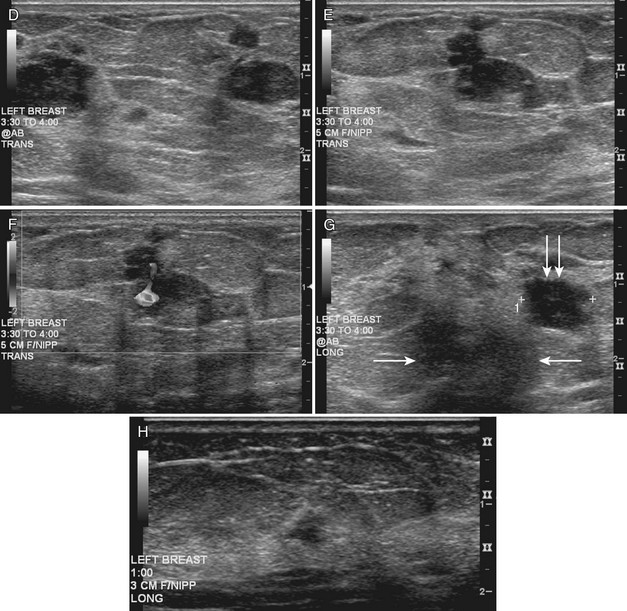

On ultrasound, Cole-Beuglet and colleagues describe typical fibroadenomas as solid masses with well-circumscribed, round or oval borders and containing weak low-level homogeneous internal echoes with enhanced, decreased, or unchanged sound transmission. Stavros and colleagues and Fornage and colleagues have described fibroadenomas as smooth, wider than tall solid masses. Stavros and colleagues further characterize fibroadenomas as having at most four gentle lobulations and homogeneous internal echo texture (Box 5-7 and Fig. 5-12A to C).

Box 5-7

Benign Mass Characteristics

Ellipsoid shape (wider than tall)

Four or fewer gentle lobulations

Intense homogeneous hyperechogenicity (in comparison to fat)

From Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, et al: Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions, Radiology 196:123–134, 1995.

Fibroadenoma appearances, however, can be highly variable (see Fig. 5-12D and E). Fibroadenomas may occasionally display irregular margins, inhomogeneous echo texture, lobulated borders, or posterior acoustic shadowing. These atypical features result in biopsy of the fibroadenoma to exclude cancer.

Stavros and colleagues also described specific ultrasound features of benign solid masses (see Box 5-7): smooth margins with fewer than four gentle lobulations, intense homogeneous hyperechogenicity, thin echogenic pseudocapsule, wider than tall elongated appearance, and no malignant sonographic signs. Suspicious ultrasound findings include acoustic shadowing, microlobulation, microcalcifications, ductal extension, angulated margins, or a very hypoechoic pattern (Box 5-8). In their 1995 study, Stavros and colleagues compared large-core needle or surgical biopsy pathology to prospectively determined ultrasound features of solid breast masses to see if the ultrasound criteria could predict malignancy. When the sonographic findings were benign by their criteria, the results yielded 424 true negatives and 2 false negatives. The negative predictive value was 99.5% and the sensitivity was 98.4% with strict adherence to their benign ultrasound features. However, it is also known that some well-circumscribed carcinomas may simulate fibroadenomas and should undergo biopsy if new or in the appropriate clinical setting (see Fig. 5-12H to J) because not all round or oval solid masses are benign (Box 5-9).

After finding a mass by ultrasound, it is important to re-evaluate the mammogram to make sure the ultrasound findings represent the mammographic findings on the film. The mammogram may provide important clues to the correct diagnosis. For example, if there are calcifications in a mass on ultrasound, the mass may be a typical calcifying fibroadenoma, benign fat necrosis, or calcifying cancer. By placing a skin marker over the ultrasound finding and retaking a mammogram, one can analyze the calcifications further and make a diagnosis. This is especially true if the calcifications found by ultrasound show up on the mammogram as typical for fibroadenoma (popcorn-type) or cancer (pleomorphic) (see Fig. 5-9K and L).

It is also important to scan masses in orthogonal planes and at multiple angles to see all the borders. A mass that appears round in one plane might actually be the cross-section of an oval mass (see Fig 5-9M and N). Scanning carefully in multiple planes allows the sonographer to evaluate both the true mass shape and all the margins of the mass.

Palpable pseudolesions can be produced by fatty deposits or oil cysts in the breast. A mammogram taken with a skin marker on the palpable mass should clarify that the mass is actually a fatty deposit or an oil cyst by showing only fat under the marker. When a fatty pseudomass is scanned from various projections, the masslike appearance of the fatty lobule should blend into the surrounding tissue and lack three-dimensional features. Oil cysts are well-circumscribed cystic or fat echogenic masses on ultrasound. If unsure if an ultrasound finding represents a fatty lobule, the sonographer can place a skin marker over the ultrasound finding and repeat the mammogram (see Fig. 5-9O to Q). If the finding is a fatty mass, there should be only fat under the skin marker.

Other benign solid breast masses include papillomas, hamartomas, lymph nodes, and healed postsurgical scars. In these various benign conditions, the clinical setting and mammographic appearance usually help identify the true nature of the lesion because sonographic features alone are rarely diagnostic (except in the case of lymph nodes). Examples of these masses are shown in Chapter 4.

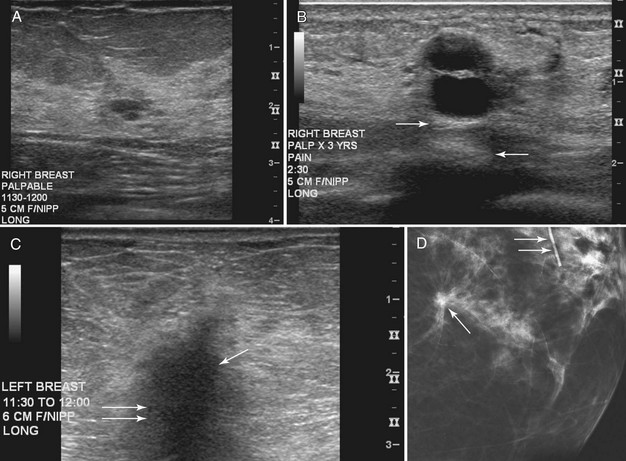

Malignant Solid Masses

Cancers are generally hypoechoic relative to the brightly echogenic normal fibroglandular tissue. They often have irregular or round shapes and angulated or spiculated margins. Cancers often can show invasion by extending through normal breast planes (“taller than wide”) and may have an echogenic halo. They can show posterior acoustic shadowing, which is a dark band posterior to the mass that is reported to occur in 60% to 97% of spiculated carcinomas. Posterior acoustic shadowing is extremely suspicious for cancer and is thought to relate to fibrosis or collagen associated with the tumor. Acoustic shadowing is different from edge shadowing, which is an artifact caused by the edge of the mass against normal breast tissue. To distinguish edge shadowing from true acoustic shadowing, the sonographer scans from different planes. Edge shadowing will not persist in all planes, but true acoustic shadowing will persist. Examples of breast cancers on ultrasound are shown in Figures 5-13 to 5-15.

The ACR BI-RADS® ultrasound lexicon and terms developed by Stavros and colleagues include features that suggest cancer, such as margins that are angulated, indistinct, microlobulated, or spiculated; acoustic shadowing; microcalcifications; ductal extension; an echogenic halo; and a taller than wide configuration (see Box 5-8 and Table 5-2).

However, one cannot always be sure that round, well-circumscribed masses are benign. Unfortunately, round circumscribed solid cancers simulate benign breast masses on ultrasound. The most common round breast cancer is invasive ductal cancer (Box 5-10). The round form of invasive ductal cancer is an uncommon form of the most common cancer. Although the round, circumscribed form is uncommon for invasive ductal cancer, invasive ductal cancers are so common that a round cancer is statistically likely to be invasive ductal cancer (Fig. 5-16A). Other round, circumscribed malignancies include medullary, solid papillary, and colloid (mucinous) carcinoma. These cancers can simulate benign fibroadenomas on ultrasound by appearing round or oval in shape with enhanced transmission of sound (see Fig. 5-16B and C).

Careful attention to the margins of a mass may prompt biopsy and suggest cancer when, at first glance, the margins appear to be circumscribed. The borders of some tumors may appear circumscribed in one scan plane but irregular in another plane, so it is important to scan in multiple planes to evaluate all mass borders for margin irregularity (see Fig. 5-16D).

Necrosis or mucin within cancers may produce anechoic regions, resulting in posterior acoustic enhancement of sound, thereby mimicking the enhanced transmission of sound seen in cysts. Thus, some benign sonographic features of fibroadenomas and benign complex cystic lesions can also be seen in round malignancies (Table 5-4).

| Finding | Look-Alikes |

|---|---|

| Fibroadenoma |

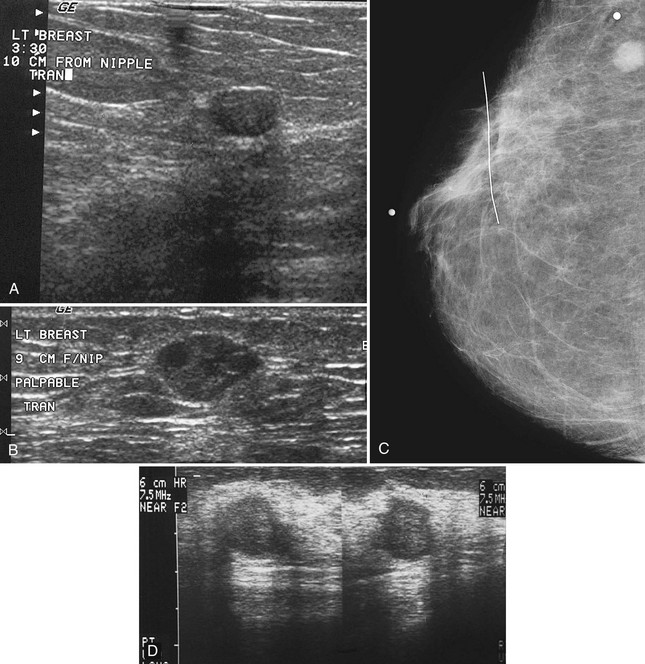

Some of the larger calcifications in breast cancer may be seen by ultrasonography, but this important diagnostic sign is not generally visualized with regularity by ultrasound (Fig. 5-17A and B).

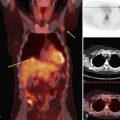

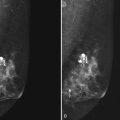

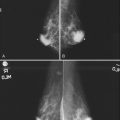

Figure 5-17 Features of malignancy on ultrasound. A, This invasive ductal cancer has microlobulated borders and bright internal echoes, representing calcifications within the tumor. B, A landscape overview shows the invasive ductal cancer of part A with its internal calcifications and a smaller second tumor slightly inferior and lateral to it. C to G, Axillary metastasis. C, A mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram shows a dense breast with an abnormal dense lymph node in the axilla. D, Ultrasound of a palpable mass in the breast tissue on the ipsilateral side, not seen on the mammogram, shows a circumscribed lobulated mass with enhanced transmission of sound that represents an invasive ductal cancer. E, Ultrasound of the abnormal lymph node in the axilla shows a hypoechoic mass without a fatty hilum that represents lymphadenopathy from the metastasis. Contrast the abnormal lymph node with the normal lymph node shown in Figure 5-1G. F, On the MLO mammogram, a huge dense abnormal lymph node is evident in the axilla. G, Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic mass so homogeneous that it almost looks like a cyst. Biopsy findings were consistent with lymphoma. H, A hypoechoic, irregular invasive ductal cancer with angulated margins is not parallel and has indistinct borders. I to K, Inflammatory cancer in a male with red skin nodules. I, MLO mammograms show bilateral gynecomastia with an irregular right retroareolar mass, skin and nipple thickening, and a second mass in the axilla. J, Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic spiculated and angulated retroareolar mass with acoustic shadowing and thickening of the areola–nipple complex. K, Ultrasound of the skin changes and red nodules shows marked skin thickening and a hypoechoic mass in the skin from inflammatory cancer.

Abnormal lymph nodes in the axilla are hypoechoic oval masses without a fatty hilum (see Fig. 5-17C to E). Lobulated or irregular abnormal lymph node borders or a thickened lymph node cortex can also indicate metastatic disease. Benign reactive lymph nodes cannot be reliably differentiated from lymph nodes containing metastases or lymphoma (see Fig. 5-17F and G). On the other hand, one cannot tell if a normal-appearing lymph node contains occult metastases. In the setting of known cancer, referring physicians may request needle biopsy of lymph nodes to make a diagnosis of metastatic disease before surgery or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Secondary signs of breast cancer include skin thickening, architectural distortion, breast edema, and retraction of Cooper ligaments (Box 5-11; see also Fig. 5-17H). Inflammatory carcinomas may have all of these signs, as well as marked attenuation of the sound beam due to breast edema (see Fig. 5-17I to K).

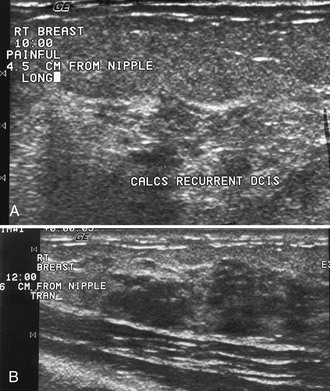

Breast Calcifications

Although mammography effectively detects calcifications in DCIS, ultrasound is limited in finding calcifications because the calcifications may be lost in the normal speckle artifact of normal breast tissue (Fig. 5-18A). On ultrasound, DCIS looks like multiple dark hypoechoic nodules or enlarged knobby ducts that may conglomerate into a mass. This is because DCIS expands normal ducts. Ultrasound is much better at finding invasive breast cancer as breast masses than in detecting breast calcifications, unless the calcifications are associated with a mass. In a 2004 study of 111 women with breast cancer by Berg, mammography was compared with ultrasound for detection of invasive and noninvasive breast cancer. Ultrasound showed 12% (129/139) of invasive breast cancers and 47% (18/38) of DCIS, whereas mammography depicted 71% (99/139) of invasive cancers and 55% (21/38) of DCIS. Thus, mammography is better at showing calcifications than ultrasound.

On occasion, highly aggressive DCIS shows up on ultrasound as hypoechoic masses, as reported by Soo and colleagues, Huang and colleagues, and Moon and colleagues (see Fig. 5-18B). Nondetection of DCIS calcifications is reported by others when ultrasound is used as a primary and stand-alone method of breast cancer screening. The nondetection of calcifications alone may limit ultrasound’s use as a stand-alone screening modality, discussed in this chapter in the section, “Breast Cancer Screening with Ultrasound.”

Palpable or Mammographically Detected Findings Undetected by Ultrasound

Benign fibrofatty nodules, areas of dense glandular tissue, benign breast tissue, or breast cancer all may be felt as a mass or lump by the patient or her physician. Ultrasound can be normal when scanning directly over the palpable finding (Fig. 5-19). If the mammogram is normal, the patient is directed back to her referring physician for management of the palpable mass. In these cases, management of the palpable mass is based on clinical grounds alone. The decision may be made to perform biopsy based solely on the physical examination because some cancers are missed by both mammography and ultrasound, and the only indication of cancer is the palpable breast lump.

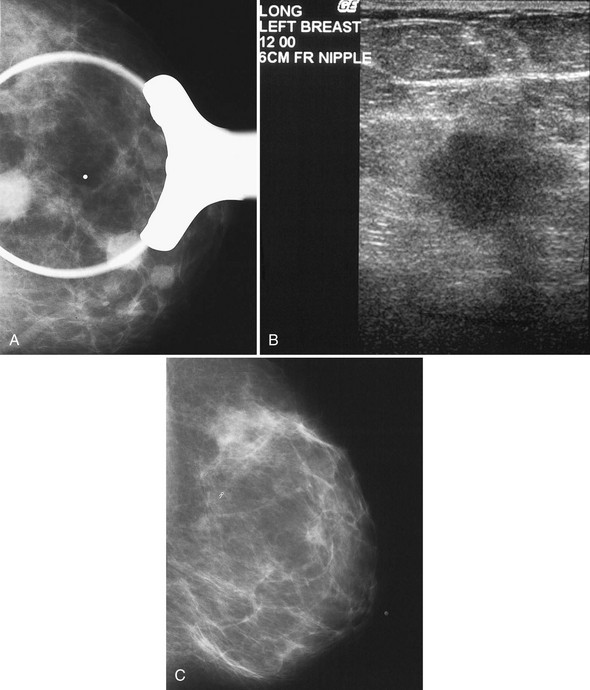

Young Patients and Palpable Findings in Dense Breasts

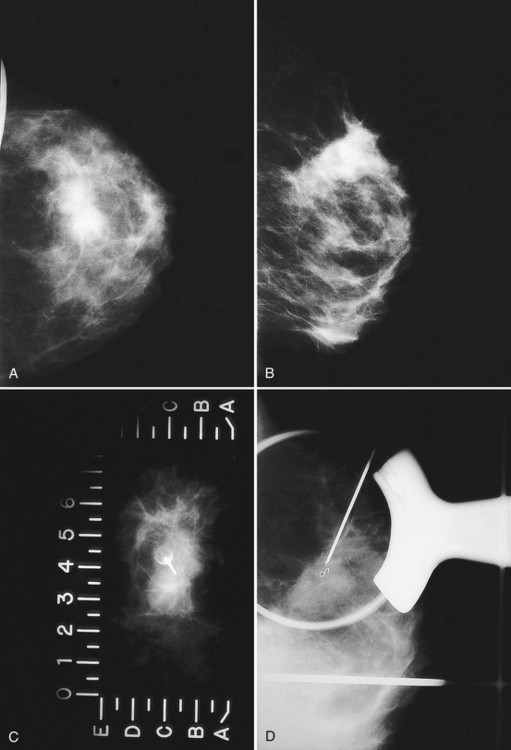

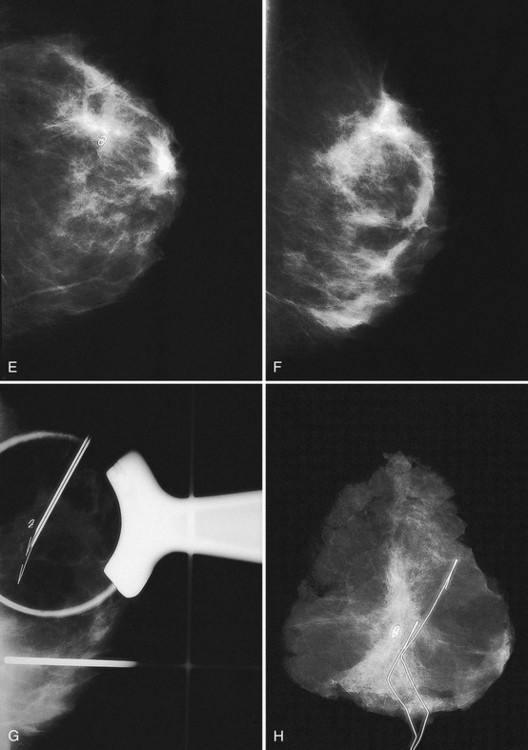

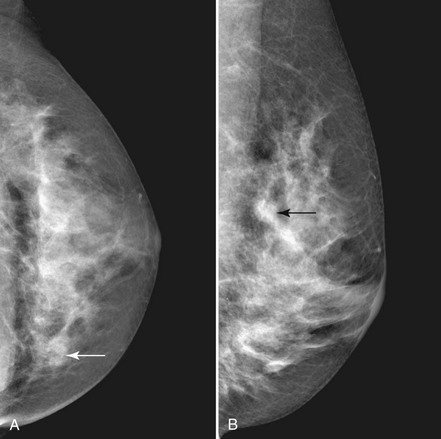

Invasive cancers can hide in the dense breast tissue on some views and may initially be seen as a “one-view-only” finding. Some invasive cancers may be palpable but not seen at all by mammography. Ultrasound can be extremely helpful when one suspects a mass that can be seen on only one view or if it is palpable and suspicious. However, ultrasound should be used only after the full mammographic workup is complete (Fig. 5-20).

Ultrasound may confirm that a suspicious finding on one view only is actually overlapping breast tissue rather than a real mass (see Fig. 5-20H). If no mass is seen on breast ultrasound, the decision for biopsy of the palpable finding is based on clinical grounds alone because some cancers are “invisible” to ultrasound.

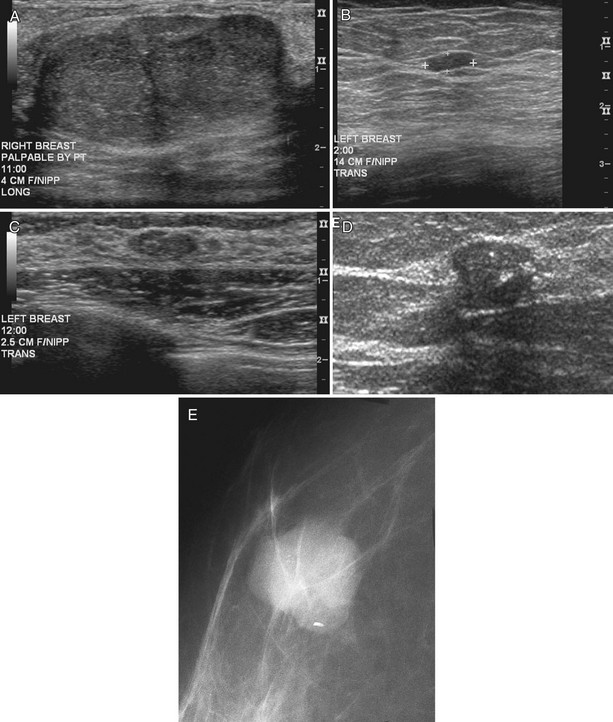

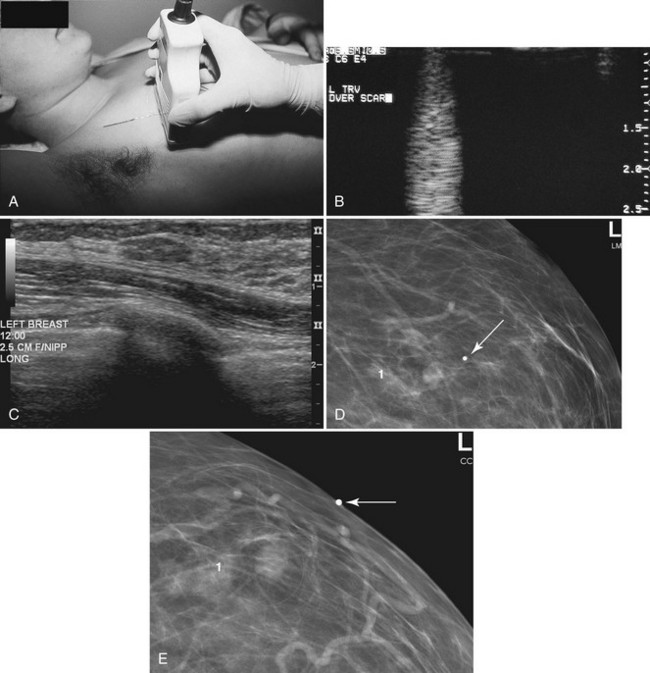

Correlating Mammographic Findings with Ultrasound Findings

When ultrasound finds a mass that was initially discovered by mammography, the next step is to determine whether the ultrasound finding and the mammographic finding represent the same thing. To accomplish this, the sonographer places a metallic skin marker over the ultrasound finding and repeats the mammogram. To determine where to place the skin marker, the sonographer scans directly over the finding and slides a finger, jumbo paper clip, or cotton-tipped swab under the transducer so that it overlies the ultrasound finding (Fig. 5-21A). This produces a ring-down shadow over the finding (see Fig. 5-21B). Once the ring-down shadow overlies the finding, the sonographer removes the transducer, leaving the fingertip, paper clip, or cotton-tipped swab on top of the skin over the mass. The sonographer marks that spot on the skin with a permanent ink marker, then places a radiopaque skin marker on the ink spot and takes a craniocaudal and mediolateral mammogram. The skin marker should correlate with the mammographic finding if the ultrasound and mammography findings are one and the same. Because the lesion may be deep in the breast, the skin marker may be compressed a few centimeters away from the lesion on the follow-up mammogram (see Fig. 5-21C to E).

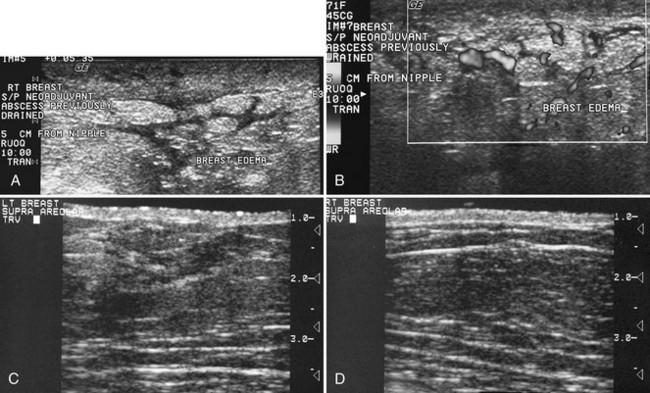

Breast Edema

Breast edema occurs in women with mastitis, inflammatory cancer, radiation therapy, postbiopsy trauma, or blockage of lymphatic drainage by various etiologies (Box 5-12). On physical examination an edematous breast is heavy and boggy. The skin may show peau d’orange, or orange-peel skin, in which skin pitting occurs where hair follicles hold the skin down and the surrounding tissues rise up with edema. On ultrasound, breast edema shows skin thickening greater than 2 to 3 mm. When compared with the contralateral breast, the edematous subcutaneous fat is gray as a result of fluid leakage, the normally sharp Cooper ligaments are less well defined, and breast tissue loses the sharp clarity of individual structures because the edema blurs normal breast landmarks. On occasion, dermal and subdermal lymphatics may become engorged and filled with fluid, producing fluid-filled branching tubules simulating blood vessels or ducts (Fig. 5-22A). Fluid-filled lymphatics can be distinguished from blood vessels by Doppler ultrasound; blood vessels will show pulsation, but fluid-filled lymphatics will show no flow (see Fig. 5-22B). Fluid-filled lymphatics will parallel the skin surface and branch quickly along the superficial layers of the breast. Fluid-filled lymphatics are easily distinguished from normal fluid-filled breast because breast ducts are larger than lymphatics and should branch and converge on the nipple.

The key to identifying breast edema is to look for fat that is grayer and skin that is thicker in comparison to the normal contralateral breast (see Fig. 5-22C and D). In a normal breast the fat is dark, and Cooper ligaments and breast structures are sharply demarcated. In an edematous breast the fat is gray, and normal breast structures are less well defined.

Breast edema in inflammatory breast cancer can cause tremendous skin thickening and breast enlargement that attenuates both the x-ray and ultrasound beams because of the enlarged, dense breast tissue filled with fluid and tumor (see Fig. 5-22 E to G).

Mastitis and Breast Abscess

On ultrasound, an abscess is an irregular but focal fluid collection that is ill-defined along its edges in the early phases and may be either irregular or well encapsulated in later phases (Fig. 5-23A). A breast abscess usually does not contain air (unlike abscesses in other parts of the body). The abscess can be hard to see because surrounding breast edema obscures normal breast structures. An abscess may contain only one pocket of pus that can be drained by a needle (see Fig. 5-23B); at other times, they may have multiple septae, contain debris or thick pus that cannot be drained without using a larger needle or leaving a catheter in place (see Fig. 5-23C and D). In larger abscesses, percutaneous drainage may help palliate the patient until surgery can be arranged. Although air does not usually occur in breast abscess, percutaneous abscess drainage can introduce air into the biopsy cavity.

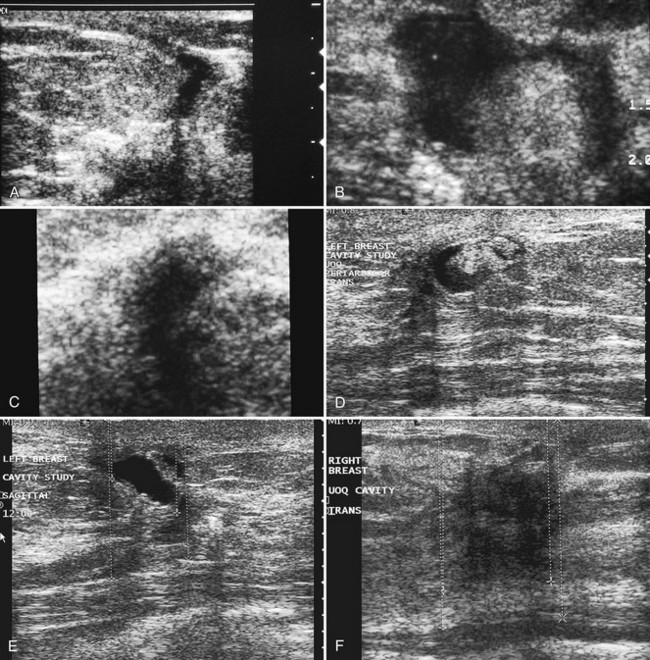

Breast Biopsy Scars

In patients undergoing lumpectomy for cancer, the surgeon excises the tumor and closes only the subcutaneous tissues and the skin above the cavity. The lumpectomy cavity fills with fluid afterward. Right after surgery, the biopsy bed is a fluid-filled pocket on ultrasound, is hypoechoic, and may have a sharp or ill-defined edematous rim with or without shadowing. Careful scanning over the skin biopsy scar shows the thickened skin at the incision and distortion of breast tissue along the incision from the skin surface to the biopsy scar (Fig. 5-24A). Later, serous fluid in the biopsy cavity may be totally clear or may contain solid debris or fibrous septa that move during real-time scanning (see Fig. 5-24B). Subsequently, the biopsy scar fills in with granulation tissue and becomes fibrotic, forming a hypoechoic spiculated mass with or without acoustic shadowing that mimics a spiculated breast cancer (see Fig. 5-24C to F).

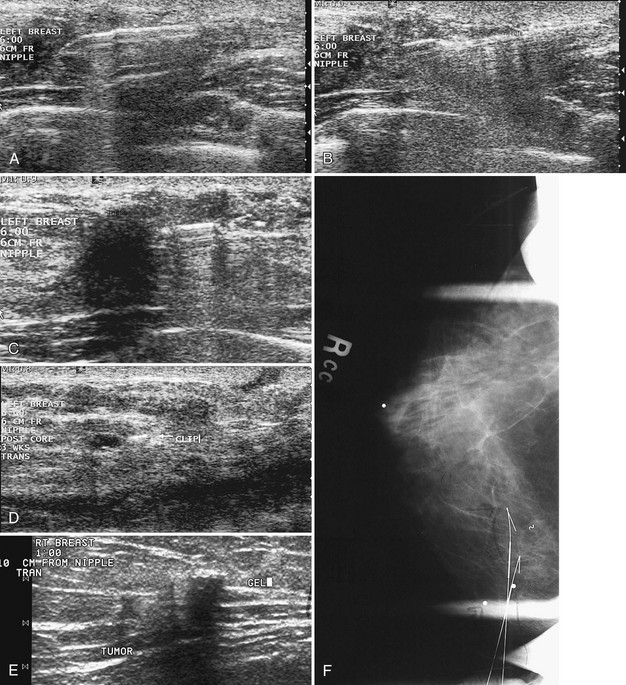

Cancers Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

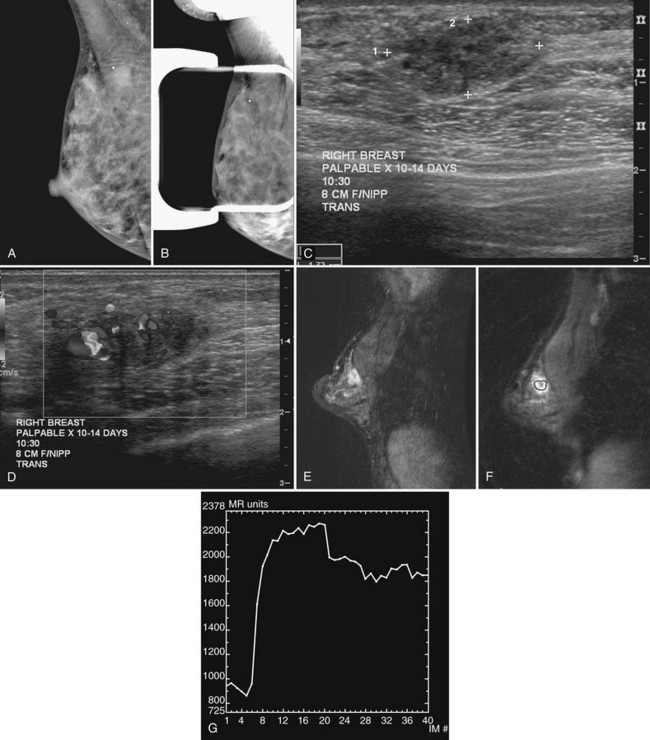

In the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, ultrasound can guide percutaneous biopsy to establish a histologic diagnosis as needed, determine initial tumor size and extent, document treatment response, and evaluate for residual tumor after chemotherapy (Fig. 5-25). Magnetic resonance imaging is another tool used for detecting both disease extent and chemotherapy response. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the original tumor site is often resected to establish the type and extent of residual tumor. This information is important for predicting prognosis. A complete pathologic response (no residual cancer in the original tumor bed by histology) is a good prognostic indicator. Surgical lumpectomy with negative margins also helps to determine whether breast-conserving therapy is an option.

Because some tumors become undetectable by both clinical examination and imaging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the radiologist may place a metallic marker in the tumor under imaging guidance before the patient undergoes chemotherapy (Fig. 5-26). Then, if all traces of the tumor fade with chemotherapy, the marker will show the location of the original tumor site and can be used for subsequent preoperative needle localization to excise the now-invisible tumor bed.

Postbiopsy Breast Markers and Core Biopsy Sites

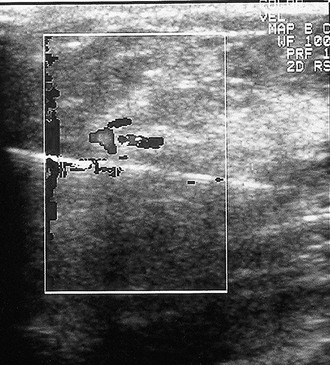

Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy methods may actually remove an entire lesion. Usually, air or fluid is present in the biopsy track, in the biopsy site, or in a hematoma immediately after vacuum-assisted core biopsy. Air and fluid are absorbed relatively quickly after biopsy. After hematoma resorption, the only ultrasound findings are often residua of the original mass, if any remains (Fig. 5-27A to C). This is a problem if the entire lesion is removed and shows cancer, requiring surgical excisional biopsy. Fluid, air, or blood accumulating in the biopsy cavity may resorb before the surgery date and cannot be relied on to guide the surgeon. To solve this problem, tiny permanent metallic markers were developed to place in the biopsy site during percutaneous needle biopsy. The metallic marker provides a landmark in the biopsy cavity to guide subsequent mammographic or ultrasonographic preoperative needle localization.

On ultrasound, the metallic markers look like tiny bright echogenic lines, but the metallic marker echo can be lost in the speckle artifact of normal breast tissue (see Fig. 5-27D). To overcome problems in imaging the metallic markers by ultrasound, some manufacturers encase the markers in echogenic pledgets composed of various materials. The radiologist places the pledgets and their encased metallic markers through a vacuum-assisted biopsy probe or directly through a separate needle deployment device under ultrasound guidance. The pledgets are radiolucent and invisible to mammography, but they are detectable as echogenic lines or plugs on ultrasound (see Fig. 5-27E). These pledgets are absorbed by the body at a slower rate than blood or seromas and were developed primarily to be targets for subsequent ultrasound-guided preoperative needle localization. If using these pledgets, the radiologist should be familiar with the pledget resorption rate for the specific manufacturer.

Color Doppler, Power Doppler, Ultrasound Contrast Agents, Three-Dimensional Imaging, and Elastography

Color Doppler and power Doppler ultrasound depict the location of blood vessels when planning the trajectory of a percutaneous breast biopsy needle (Fig. 5-28). As a diagnostic tool, color and power Doppler imaging may show swirling debris in cysts or pulsating blood vessels within breast masses (Fig. 5-29).

Key Elements

Breast ultrasound is a useful adjunct to mammography and clinical examination, particularly for the diagnosis of cysts and in certain other limited settings.

Ultrasound results should be considered in conjunction with mammographic and clinical findings to avoid misdiagnosis.

Cysts are anechoic, round or oval, well-circumscribed masses with imperceptible walls and enhanced transmission of sound.

Fibroadenomas are classically described as ellipsoid, well-circumscribed masses with fewer than four gentle lobulations, and they are wider than tall.

Overlap is noted in the ultrasound appearance of benign fibroadenomas and well-circumscribed breast cancers.

Suspicious ultrasound findings in solid masses include acoustic spiculation; shadowing; taller than wide configuration; angulated, indistinct, microlobulated, or spiculated margins; irregular shape; and an echogenic halo.

Secondary signs of breast cancer on ultrasound are changes in Cooper ligaments, breast edema, architectural distortion, skin thickening, skin retraction or irregularity, and suspicious microcalcifications.

Cystic breast masses include breast cysts, complex breast cysts, intracystic carcinoma or papilloma, mucinous cancer, necrotic cancer, abscess, seroma, hematoma, and galactocele.

Solid round or oval masses include fibroadenoma, papilloma, cancer (invasive ductal, medullary, mucinous, papillary), metastasis, and phyllodes tumor.

The most common round cancer is invasive ductal cancer, an uncommon form of a very common tumor.

Multiple solid masses include fibroadenomas, papillomas, multiple breast cancers, and metastases.

Breast edema is characterized by skin thickening, gray fat, loss of crisply defined breast structures, increased breast thickness when compared with the contralateral side and, occasionally, fluid-filled lymphatics.

Breast abscesses are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus, are generally subareolar, and cause a hot, painful hypoechoic pus-filled mass with surrounding breast edema.

Breast biopsy scars look just like cancer on ultrasound after the seroma is resorbed, and correlation with the skin scar and surgical history is necessary.

Metallic markers may be placed in breast biopsy cavities or in tumors before neoadjuvant chemotherapy to guide subsequent preoperative needle localization.

Mammography is the gold standard for breast cancer screening, and supplemental screening by MRI produces the highest cancer sensitivity.

Mammography with ultrasound as a supplemental study might be an option for women with dense breasts who cannot undergo MRI, but there is a shortage of trained sonographers and no insurance reimbursement for screening ultrasound in the United States.

Abe H, Schmidt RA, Kulkarni K, et al. Axillary lymph nodes suspicious for breast cancer metastasis: sampling with US-guided 14-gauge core-needle biopsy—clinical experience in 100 patients. Radiology. 2009;250:41-49.

American College of Radiology. American College of Radiology Standards. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2002. pp 593–595

American College of Radiology: Illustrated Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®), ed 4. Reston, VA, American College of Radiology (in press).

Baker JA, Soo MS. Breast US: Assessment of technical quality and image interpretation. Radiology. 2002;223:229-238.

Bedi DG, Krishnamurthy R, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Cortical morphologic features of axillary lymph nodes as a predictor of metastasis in breast cancer: in vitro sonographic study. AJR. 2008;191:646-652.

Berg WA. Rationale for a trial of screening breast ultrasound: American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) 6666. AJR. 2003;180:1225-1228.

Berg WA. Sonographically depicted breast clustered microcysts: is follow-up appropriate? AJR. 2005;185:952-959.

Berg WA. Tailored supplemental screening for breast cancer: what now and what next? AJR. 2009;192:390-399.

Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al. Lesion detection and characterization in a breast US phantom: results of the ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Radiology. 2006;239:693-702.

Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB. Operator dependence of physician-performed whole-breast US: lesion detection and characterization. Radiology. 2006;241:355-365.

Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs. mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:2151-2163.

Berg WA, Campassi CI, Ioffe OB. Cystic lesions of the breast: sonographic–pathologic correlation. Radiology. 2003;227:183-191.

Berg WA, Gutierrez L, Ness Aiver MS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, US, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Radiology. 2004;233:830-849.

Birdwell RL, Ikeda DM, Jeffrey SS, et al. Preliminary experience with power Doppler imaging of solid breast masses. AJR. 1997;169:703-707.

Brookes MJ, Bourke AG. Radiological appearances of papillary breast lesions. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1265-1273.

Buchberger W, DeKoekkoek-Doll P, Springer P, et al. Incidental findings on sonography of the breast: clinical significance and diagnostic workup. AJR. 1999;173:921-927.

Burnside ES, Hall TJ, Sommer AM, et al. Differentiating benign from malignant solid breast masses with US strain imaging. Radiology. 2007;245:401-410.

Chao TC, Chao HH, Chen MF. Sonographic features of breast hamartomas. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(4):447-453.

Chopra S, Evans AJ, Pinder SE, et al. Pure mucinous breast cancer—mammographic and ultrasound findings. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:421-424.

Cole-Beuglet C, Soriano RZ, Kurtz AB, Goldberg BB. Ultrasound analysis of 104 primary breast carcinomas classified according to histologic type. Radiology. 1983;147:191-196.

Cole-Beuglet C, Soriano RZ, Kurtz AB, Goldberg BB. Fibroadenoma of the breast: sonomammography correlated with pathology in 122 patients. AJR. 1983;140:369-375.

Corsetti V, Ferrari A, Ghirardi M, et al. Role of ultrasonography in detecting mammographically occult breast carcinoma in women with dense breasts. Radiol Med (Torino). 2006;111:440-448.

Corsetti V, Houssami N, Ferrari A, et al. Breast screening with ultrasound in women with mammography-negative dense breasts: evidence on incremental cancer detection and false positives, and associated cost. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:539-544.

Dennis MA, Parker SH, Klaus AJ, et al. Breast biopsy avoidance: the value of normal mammograms and normal sonograms in the setting of a palpable lump. Radiology. 2001;219:186-191.

Doshi DJ, March DE, Crisi GM, Coughlin BF. Complex cystic breast masses: diagnostic approach and imaging—pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(Suppl 1):S53-S64.

DuPont WD, Page DL, Pari FF, et al. Long-term risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;351:10-15.

Fornage BD, Lorigan JG, Andry E. Fibroadenoma of the breast: sonographic appearance. Radiology. 1989;172:671-675.

Gordon PB. Ultrasound for breast cancer screening and staging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:431-441.

Gordon PB, Goldenberg SL. Malignant breast masses detected only by ultrasound. A retrospective review. Cancer. 1995;76:626-630.

Graf O, Helbich TH, Hopf G, et al. Probably benign breast masses at US: is follow-up an acceptable alternative to biopsy? Radiology. 2007;244:87-93.

Hashimoto BE, Kramer DJ, Picozzi VJ. High detection rate of breast ductal carcinoma in situ calcifications on mammographically directed high-resolution sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:501-508.

Hilton SW, Leopold GR, Olson LK, Wilson SA. Real time breast sonography: application in 300 consecutive patients. AJR. 1986;147:479-486.

Huang CS, Wu CY, Chu JS, et al. Microcalcifications of nonpalpable breast lesions detected by ultrasonography: correlation with mammography and histopathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:431-436.

Jain A, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Lange J, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of axillary nodes in the staging of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:462-471.

Kaplan SS. Clinical utility of bilateral whole-breast US in the evaluation of women with dense breast tissue. Radiology. 2001;221:641-649.

Kim EK, Ko KH, Oh KK, et al. Clinical application of the BI-RADS final assessment to breast sonography in conjunction with mammography. AJR. 2008;190:1209-1215.

Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Occult cancer in women with dense breasts: detection with screening US—diagnostic yield and tumor characteristics. Radiology. 1998;207:191-199.

Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165-175.

Kopans DB, Meyer JE, Lindfors KK, et al. Breast sonography to guide cyst aspiration and wire localization of occult solid lesions. AJR. 1984;143:489-492.

Kopans DB, Meyer JE, Lindfors KK. Whole-breast US imaging: four year follow-up. Radiology. 1985;157:505-507.

Lee E, Wylie E, Metcalf C. Ultrasound imaging features of radial scars of the breast. Australas Radiol. 2007;51:240-245.

Lee JW, Han W, Ko E, et al. Sonographic lesion size of ductal carcinoma in situ as a preoperative predictor for the presence of an invasive focus. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:15-20.

Lehman CD, Isaacs C, Schnall MD, et al. Cancer yield of mammography, MR, and US in high-risk women: prospective multi-institution breast cancer screening study. Radiology. 2007;244:381-388.

Liberman L, Feng TL, Dershaw DD, et al. US-guided core breast biopsy: use and cost-effectiveness. Radiology. 1998;208:717-723.

Mendelson EB, Berg WA, Merritt CR. Toward a standardized breast ultrasound lexicon, BI-RADS: ultrasound. Semin Roentgenol. 2001;36:17-25.

Mercado CL, Guth AA, Toth HK, et al. Sonographically guided marker placement for confirmation of removal of mammographically occult lesions after localization. AJR. 2008;191:1216-1219.

Meyer JE, Amin E, Lindfors KK. Medullary carcinoma of the breast: mammographic and US appearance. Radiology. 1989;170:79-82.

Moon WK, Im JG, Koh YH, et al. US of mammographically detected clustered microcalcifications. Radiology. 2000;217:849-854.

Moon WK, Myung JS, Lee YJ, et al. US of ductal carcinoma in situ. Radiographics. 2002;22:269-280.

Moon WK, Noh DY, Im JG. Multifocal, multicentric, and contralateral breast cancers: bilateral whole-breast US in the preoperative evaluation of patients. Radiology. 2002;224:569-576.

Murphy IG, Dillon MF, Doherty AO, et al. Analysis of patients with false negative mammography and symptomatic breast carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:457-463.

Nicholson BT, Harvey JA, Cohen MA. Nipple–areolar complex: normal anatomy and benign and malignant processes. Radiographics. 2009;29:509-523.

Parker SH, Jobe WE, Dennis MA, et al. US-guided automated large-core breast biopsy. Radiology. 1993;187:507-511.

Raza S, Chikarmane SA, Neilsen SS, et al. BI-RADS 3, 4, and 5 lesions: value of US in management—follow-up and outcome. Radiology. 2008;248:773-781.

Reuter K, D’Orsi CJH, Reale F. Intracystic carcinoma of the breast: the role of ultrasonography. Radiology. 1984;153:233-234.

Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G, et al. Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1040-1047.

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

Schneck CD, Lehman DA. Sonographic anatomy of the breast. Semin Ultrasound. 1982;3:13-33.

Schrading S, Kuhl CK. Mammographic, US, and MR imaging phenotypes of familial breast cancer. Radiology. 2008;246:58-70.

Sickles EA. Sonographic detectability of breast calcifications. SPIE. 1983;419:51-52.

Sickles EA, Filly RA, Callen RW. Breast cancer detection with sonography and mammography: comparison using state-of-the-art equipment. AJR. 1983;140:843-845.

Sickles EA, Filly RA, Callen PW. Benign breast lesions: ultrasound detection and diagnosis. Radiology. 1984;151:467-470.

Skaane P, Sauer T. Ultrasonography of malignant breast neoplasms. Analysis of carcinomas missed as tumor. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:376-382.

Soo MS, Baker JA, Rosen EL, et al. Sonographically guided biopsy of suspicious microcalcifications of the breast: a pilot study. AJR. 2002;178:1007-1015.

Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, et al. Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Radiology. 1995;196:123-134.

Stomper PC, D’Souza DJ, DiNitto PA, Arredondo MA. Analysis of parenchymal density on mammograms in 1353 women 25–79 years old. AJR. 1996;167:1261-1265.

Tabár L, Péntek Z, Dena PB. The diagnostic and therapeutic value of breast cyst puncture and pneumocystography. Radiology. 1981;141:659-663.

The WL, Wilson AR, Evan AJ, et al. Ultrasound guided core biopsy of suspicious mammographic calcifications using high frequency and power Doppler ultrasound. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:390-394.

Thomas A, Warm M, Hoopmann M, et al. Tissue Doppler and strain imaging for evaluating tissue elasticity of breast lesions. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:522-529.

Vade A, Lafita VS, Ward KA, et al. Role of breast sonography in imaging of adolescents with palpable solid breast masses. AJR. 2008;191:659-663.

Weind KL, Maier CF, Rutt BK, Moussa M. Invasive carcinomas and fibroadenomas of the breast: comparison of microvessel distributions—implications for imaging modalities. Radiology. 1998;208:477-483.

Zhi H, Ou B, Luo BM, et al. Comparison of ultrasound elastography, mammography, and sonography in the diagnosis of solid breast lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:807-815.

5-1. Fill in the elements for ultrasound labeling.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-2. Fill in echogenic versus hypoechoic appearances of a normal ultrasound image of breast tissue.

Skin: ____________________________________________

Fat: ____________________________________________

Glandular tissue: __________________________________

Breast ducts: _____________________________________

Nipple: __________________________________________

5-3. Fill in the simple cyst criteria.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-4. Fill in the differential diagnosis for cystic or fluid-containing masses.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-5. Fill in the benign mass characteristics.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-6. Fill in the suspicious ultrasound characteristics of solid breast masses.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-7. Fill in the differential diagnosis of round or oval solid breast masses.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5-8. Fill in the secondary signs of breast cancer seen on ultrasound.

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

| UNILATERAL | BILATERAL (SYSTEMIC PROBLEMS) |

|---|---|

| ____________________________ | ____________________________ |

| ____________________________ | ____________________________ |

| ____________________________ | ____________________________ |

| ____________________________ | ____________________________ |

| ____________________________ |

5-10. Fill in the descriptors for the ACR BI-RADS® ultrasound lexicon.

| Shape | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| ____________________ | ||

| Margin | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| ____________________ | ____________________ | |

| Boundary | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| Echo pattern | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| ____________________ | ____________________ | |

| ____________________ | ||

| Posterior acoustic features | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| ____________________ | ____________________ |

5-11. Fill in the unfortunate ultrasound look-alikes.

| FINDING | LOOK-ALIKES |

|---|---|

| Fibroadenoma | ________________________ |

| Solid benign mass | ________________________ |

| Complex benign mass | ________________________ |

5-12. Fill in the ultrasound features of cancer, cysts, and fibroadenomas.

| CYSTIC MASS TYPE | DESCRIPTION | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|

| Clustered microcysts | ______________________________________ | ______________________________________ |

| Complicated cysts | ______________________________________ | ______________________________________ |

| Complex mass | ______________________________________ | ______________________________________ |