Chapter 14 Breast reshaping after massive weight loss, implant based

• Staging may be appropriate for extremely large or ptotic patients.

• The circumvertical approach is a powerful tool for management of the redundant skin envelope.

• Controlled management of the IMF is key to reducing the number of later revisions.

• Use of an implant can be an excellent adjunct for restoring upper pole fullness.

• Patient education regarding the complex and in some ways potentially imperfect nature of the surgical correction can aid in helping patients understand the potential need for future revisions to obtain the optimal result.

Introduction

Since its development in 1966, bariatric surgery has become an effective modality for sustained weight loss. The growth of bariatric surgery has paralleled the burgeoning obesity epidemic in the United States.1 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has become the most effective and frequently performed means of sustained surgical weight loss, with mean weight loss at 36 months of 41 kg.2,3 Other surgical procedures include biliopancreatic diversion, adjustable gastric banding, and the creation of a gastric sleeve.4–6 Additionally, some patients are able to achieve weight loss with diet and exercise alone. Regardless of the means of weight loss, massive weight loss (MWL) is defined as weight loss of 45 kg (100 pounds) or more.7

Weight loss causes a multitude of both physiologic and anatomic changes. Severe volume loss results in skin redundancy and sagging, which can lead to issues with hygiene and the potential for infection. Song et al elegantly rated the anatomic changes that occur throughout the integumentary system after MWL.8 Additional consideration must be given to the nutritional status of MWL patients. Appropriate preoperative laboratory testing as well as consultation with a nutritionist may be advisable in these types of patients. The psychiatric changes that accompany MWL, and patient motivation for body contouring must also be considered when dealing with MWL patients.9–13

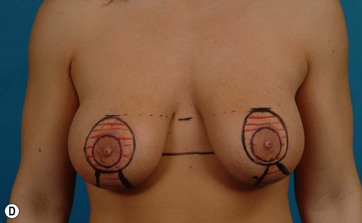

After MWL the breast undergoes a unique set of changes not typically seen in other settings. The breast becomes deflated with a paucity of upper pole tissue. Extreme ptosis of the skin envelope and the nipple can develop, along with inferior malposition of the inframammary fold (IMF). The total amount of volume loss is variable among patients. The nipple areolar complex also often becomes displaced medially. The breast mound itself can be displaced laterally and the chest wall can take on an almost barrel-shaped configuration. Additionally, the skin envelope can become inelastic14–16 (Fig. 14.1A–D). All these anatomic changes serve to make augmentation mastopexy, an already challenging procedure, even more intimidating.

Preoperative Preparation

Proper assessment of the MWL patient begins with ascertaining the method of weight loss. If the patient lost weight through surgical means then determining whether the procedure was restrictive, diversionary or both allows the surgeon to determine what nutritional workup is necessary. Timing of the bariatric procedure and the starting weight at the time of surgery, the amount of weight loss since the procedure, the weight change in the past 3–6 months, and how long the patient has been at the current weight should all be ascertained. Generally, the patient should be at a stable goal weight for 3–6 months or more prior to any plastic surgical procedure. This usually occurs 12–18 months following the weight loss surgery.17

Preoperative assessment of the MWL patient must include a full evaluation of the patient’s nutritional status. This is especially important in patients who have undergone diversionary procedures, and to a lesser extent those undergoing restrictive procedures. MWL patients that were able to lose weight through diet and exercise generally have adequate nutrition and do not need supplementation. Whether or not supplemental Vitamin B12, iron, calcium, and/or multivitamins are being used should be noted, as deficiencies here can lead to altered wound healing. Baseline laboratory values should consist of a complete blood count, electrolytes, prothrombin/partial thromboplastin time, and albumin levels.7 Micronutrients may also need to be assessed in selected cases of possible malnutrition.18–20

Discussion of potential need for revision at the initial consultation helps mitigate some of the later issues that may arise when enhancements of the initial procedure are needed. Meticulous documentation of conversations regarding revisions is also important during the initial visit. Informing patients that scar length is commensurate with the amount of soft tissue resection allows the patient insight into the outcomes of the procedure. Additionally, discussion of recurrent ptosis, or the possibility of breast asymmetry is important in the augmentation mastopexy patient.14 Nipple viability and potential nipple loss must be part included as a potential risk during augmentation mastopexy. Establishing realistic expectations and goals for surgical outcome is an important part of a successful augmentation mastopexy procedure.

Surgical Technique

Primary Augmentation Mammaplasty

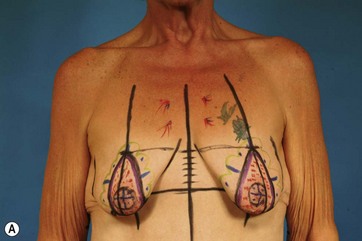

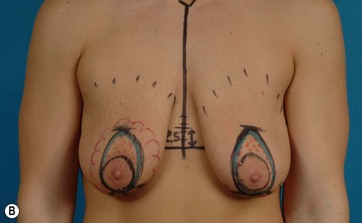

The patient is marked in the standing position with her arms resting gently at her sides (Fig. 14.2A, B). Basic landmarks including the IMF, midsternal line, and breast meridian are marked. The IMF line is communicated across the midline to allow the level of the fold to be identified without the need to manipulate the breast. In the midline, measuring up from the IMF, a distance of 4–6 cm is measured and this point is then transposed in a parallel line over to each breast meridian. This point represents the top of the periareolar pattern. Extending inferiorly, an oval is then drawn around the medial, lateral, and inferior aspect of the existing areola to complete the periareolar pattern. In the vast majority of cases, a vertical skin takeout will also be required to appropriately reduce the redundant skin envelope and lift the breast. The amount of skin to be resected can be estimated by pinching the inferior aspect of the breast below the NAC together until a pleasing shape is created. The medial and lateral aspects of the skin pinch are marked and carried down to the IMF, curving laterally as needed to create a contoured closure (Fig. 14.3A, B).

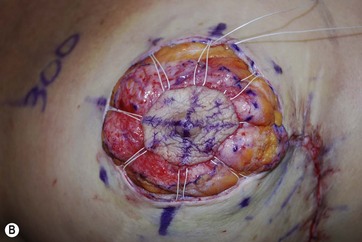

At surgery, the procedure is begun by accessing it through either the periareolar or vertical incision and the desired pocket is created, with care being taken to preserve the attachments of the IMF and avoid disruption of the dominant second intercostal perforator in the superomedial portion of the breast (Fig. 14.4). An implant sizer is then placed to create the desired volume. The skin envelope is then plicated together with staples to create the desired shape. For periareolar approaches, the proposed periareolar opening is stapled down according to the preoperative marks. For circumvertical approaches, the vertical incision is plicated together until the desired lower pole contour is created and then the periareolar portion is added. With the patient upright on the operating table, the shape and symmetry of the result is assessed (Fig. 14.5). Further plication or lifting is performed as needed to create the desired result. The patient is laid back down and the plicated edges are marked with a surgical pen and the staples are removed (Fig. 14.6A, B). With the areola under maximal stretch, a 40 mm areolar outline is marked with the aid of a circular template (Fig. 14.7). The areolar and periareolar incisions are made extending just into the superficial dermis and the redundant skin outlined by the marks is de-epithelialized along the periareolar and vertical segments (Fig. 14.8). The dermis around the periareolar incision is divided 5 mm away from the incised skin edge to create a small dermal shelf that will eventually hold the purse string suture. The edges of this shelf are undermined slightly to allow a contoured periareolar closure to be accomplished without excessive tissue bunching around the incision (Fig. 14.9A, B). With the skin and parenchyma now completely prepared for final closure, the chosen implant is inserted into the pocket. An iodoform occlusive drape is applied to the skin, with a small opening being made in the area of the skin incision. This prevents the implant from contacting the skin during insertion, thus minimizing the potential for bacterial contamination of the implant or the pocket. In circumvertical cases, the vertical segment is now closed (Fig. 14.10). The periareolar defect is managed using the interlocking Teflon suture technique.21 A PTFE suture on a straight needle is passed, joining eight evenly spaced points in both the areolar and periareolar incisions, spanning the intervening areas on the periareolar side by passing the suture in the dermal shelf. Pulling this smooth, strong and permanent suture together in a secure purse string type fashion allows control of the size and shape of the periareolar defect (Fig. 14.11A–C). A little trimming of the de-epithelialized edges to create a perfectly round shape with the final suturing completes the procedure22–27 (Figs 14.12 and 14.13).

FIG. 14.7 With the aid of a circular template, a 40 mm diameter areolar mark is made centered on the nipple.

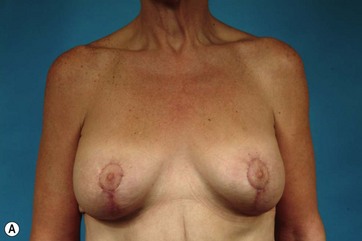

Surgical Technique – Staged Augmentation Mammaplasty

Typically, when the surgeries are staged, the mastopexy is performed first using the same periareolar or vertical approaches described earlier. This allows the surgeon to raise the NAC, reshape the breast, and reduce the breast skin envelope. Once the mastopexy is performed, the patient is allowed to heal and after a minimum of 6 months the surgeon can decide, now with fewer variables to deal with, which implant size and placement would provide the best esthetic result (Fig. 14.14A, B). The advantage of staging is that fewer variables are addressed at each procedure, thereby allowing greater accuracy with fewer complications. The disadvantage of the staged approach is that it is more costly, as two procedures are always planned as opposed to one in the combined approach. And in the case of needing to treat a complication, even a third procedure could well be required, all of which presents as a significant financial challenge for many patients. Additionally, when a combined approach does require revision, typically the revision is of a less demanding nature as opposed to a staged procedure where many of the same variables present challenges for each planned procedure.

Complications and Their Management

Recurrent Ptosis

Even despite attempts to overcorrect the degree of tightening of the breast, particularly along the vertical component, postoperative stretching of the skin with loss of an esthetic lower pole contour can occur. Here, the advantage of the combined procedure comes into play. Very often, simple retightening of the vertical component will provide very esthetic and permanent correction of this complication (Fig. 14.15A–E). When a staged procedure is performed, it can be difficult to assess the degree of tightening needed to create the desired shape. Therefore after the augmentation is performed at the second procedure, postoperative stretching of the skin envelope can then necessitate a third procedure to achieve the final desired result. A related complication relates to widening or shape distortion of the areola despite the use of the interlocking suture. Here, simple reapplication of the interlocking technique usually provides stable and long-term correction of the problem.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. Overweight and obesity: obesity trends: US overweight trends 1985-2009. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html, 2011. Accessed March 4

2 Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547–559.

3 Torres JC, Oca CF, Garrison RN. Gastric bypass: Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy from the lesser curvature. South Med J. 1983;76(10):1217–1221.

4 Mason EE. Vertical banded gastroplasty for obesity. Ann Surg. 1982;117(5):701–706.

5 Kuzmak LI. A review of seven years’ experience with silicone gastric banding. Obes Surg. 1991;1(4):403–408.

6 Scopinaro N, Gianetta E, Pandolfo N, et al. Bilio-pancreatic bypass. Proposal and preliminary experimental study of a new type of operation for the functional surgical treatment of obesity. Minerva Chir. 1976;31(10):560–566.

7 Sebastian JL. Bariatric surgery and work-up of the massive weight loss patient. Clin Plastic Surg. 2008;35(1):11–26.

8 Song AY, Jean RD, Hurwitz DJ, et al. A classification of contour deformities after bariatric weight loss: The Pittsburgh rating scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1535.

9 Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN. Psychiatric considerations of the massive weight loss patient. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35:1–10.

10 Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Fabricatore AN. Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of bariatric surgery. Obes Res. 2005;13(4):639–648.

11 Boccieri LE, Meana M, Fisher BL. A review of psychosocial outcomes of surgery for morbid obesity. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(3):155–165.

12 Herpetz S, Kielmann R, Wolf AM, et al. Does obesity surgery improve psychosocial functioning? A systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(11):1300–1314.

13 van Hout GC, van Oudheusden I, van Heck GL. Psychological profile of the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2002;14(5):479–488.

14 Losken A. Breast reshaping following massive weight loss: principles and techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(3):1075–1085.

15 Rubin JP, Khaci G. Mastopexy after massive weight loss: dermal suspension and selective auto-augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35:123–129.

16 Rubin JP. Mastopexy in the massive weight loss patient: dermal suspension and total parenchymal reshaping. Aesth Surg J. 2006;16:1622–1629.

17 Gusenoff JA, Rubin JP. Plastic surgery after weight loss: current concepts in massive weight loss surgery. Aesth Surg J. 2008;28(4):452–455.

18 Agha-Mohammadi S, Hurwitz DJ. Nutritional deficiency of post-bariatric surgery body contouring patients: what every plastic surgeon should know. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:604–613.

19 Alvarez-Leite JI. Nutrient deficiencies secondary to bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:569–575.

20 Madan AK, Orth WS, Tichansky DS, et al. Vitamin and trace mineral levels after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:603–606.

21 Hammond DC, Khuthaila DK, Kim J. The interlocking Gore-Tex suture for control of areolar diameter and shape. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:804.

22 Hammond DC, Hollender HA, Bouwense CL. The sit-up position in breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(2):572–576.

23 Hammond DC, Alfonso D, Khuthaila DK. Mastopexy using the short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(5):1533–1539.

24 Hammond DC. The short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction (SPAIR) mammaplasty. Semin Plast Surg. 2004;18(3):231–243.

25 Colen SR, Giese SY, Graf R, et al. Treatment of breast ptosis. Aesth Surg J. 2003;23(4):279–285.

26 Hammond DC. The SPAIR mammaplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):411–421.

27 Hammond DC. Short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction (SPAIR) mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(3):890–901.