Chapter 8 Breast disease and breast cancer

Benign breast diseases

The phrase benign breast diseases encompasses a heterogeneous group of lesions that may present a wide range of symptoms or may be detected as attendant microscopic findings. The incidence of benign breast lesions begins to rise during the second decade of life and peaks in the 4th and 5th decades, as opposed to malignant diseases, for which the incidence continues to increase after menopause, although at a significant less rapid pace1, 2, 3

The majority of the lesions that occur in the breast are benign4 and are far more frequent than malignant ones5, 6, 7 With the advent of screening techniques such as mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging of the breast and the extensive use of needle biopsies, the diagnosis of a benign breast disease can be accomplished without surgery in the majority of patients.

The most frequently seen benign lesions of the breast have been summarised as developmental abnormalities, inflammatory lesions, fibrocystic changes, stromal lesions, and neoplasms (see Table 8.1).

| Benign breast conditions |

|---|

| Malignant breast conditions |

Benign breast conditions — fibrocystic breast changes

Fibrocystic breast conditions (FBC) are the most common benign breast problem encountered in women. The following characteristics have been reported:8

Treatment (or management) of FBC

Lifestyle

Lifestyle changes that may be helpful include exercise, which may decrease breast tenderness. In 1study, women who walked approximately 30 minutes on most days reported less breast tenderness as well as improvement in other symptoms, such as anxiety.8

Diets

Some studies have reported that women with FBC drink more coffee than women without the disease,9, 10 whereas other studies do not.11, 12 Eliminating caffeine for less than 6 months does not appear to be effective at reducing symptoms of FBC.13, 14 However, long-term and complete avoidance of caffeine does reduce symptoms of FBC.15, 16 Some women are more sensitive to effects of caffeine than others, so benefits of restricting caffeine are likely to vary from woman to woman. Caffeine is found in coffee, black tea, green tea, cola drinks, chocolate, and many over-the-counter drugs. A decrease in breast tenderness can take 6 months or more to occur after caffeine is eliminated. Breast lumpiness may not go away, but the pain often decreases.

FBC has been linked to excess oestrogen. When women with FBC were put on a low-fat diet, their oestrogen levels decreased.17, 18 After 3–6 months, the pain and lumpiness also decreased.19,20 The link between dietary fat and symptoms appears to be most strongly related to saturated fat.21 Foods high in saturated fat include meat and dairy products. Fish, non-fat dairy, and tofu are replacements to consider.

A recent study from the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial investigated a total of 48 835 post-menopausal women, aged 50–79 years, without prior breast cancer.22 Participants were randomly assigned to the dietary modification intervention group or to the comparison group. The intervention was designed to reduce total dietary fat intake to 20% of total energy intake, and to increase fruit and vegetable intake to ≥5 servings per day and intake of grain products to ≥6 servings per day. Risk for developing benign breast disease varied by levels of baseline total vitamin D intake but it varied little by levels of other baseline variables. Hence, the results suggested that a modest reduction in fat intake and increase in fruit, vegetable, and grain intake do not alter the risk of benign proliferative breast disease. It is difficult to conclude about the importance of diet in such a study without knowing details relating to other lifestyle factors, such as behavioural and exercise habits.

Supplements

Omega-6 fatty acids

In a double-blind research trial, evening primrose oil (EPO) reduced symptoms of FBC,23 though only moderately. One group of researchers reported that EPO normalises blood levels of fatty acids in women with FBC.24 However, even these scientists had difficulty linking the improvement in lab tests with an actual reduction in symptoms. Nonetheless, most reports continue to show at least some reduction in symptoms resulting from EPO supplementation with doses of 3g/day of EPO for at least 6 months to alleviate symptoms of FBC.25, 26

Vitamins

While several studies report that 200–600IU of vitamin E per day, taken for several months, reduces symptoms of FBD,27, 28 most double-blind trials have found that vitamin E does not relieve FBC symptoms.29, 30

Vitamin B6

As with vitamin E, the effectiveness of vitamin B6 remains uncertain. The reduction of symptoms by vitamin B6 supplementation is controversial.31, 32 Since vitamin B6 supplementation is effective for relieving the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS), in addition to breast tenderness, women should discuss the use of vitamin B6 with their health care provider.

Herbal medicines

Vitex agnus castus (Chasteberry)

In 1 double-blind trial, a liquid preparation containing 32.4mg of Vitex agnus castus (VAC) and homeopathic ingredients was found to successfully reduce breast tenderness associated with the menstrual cycle (e.g. cyclic mastalgia).34 VAC is thought to reduce breast tenderness at menses because of its ability to reduce elevated levels of the hormone prolactin.35

Breast cancer — risk modification for prevention

Weight control and energy intake

There are numerous studies that report that controlling weight gain by reducing energy intake is associated with prevention of breast cancer.36, 37 Weight gain in adult life is an important risk factor for breast cancer. Observational studies indicate that pre-menopausal or post-menopausal weight loss is associated with a reduction in risk of post-menopausal breast cancer.38 On current scientific evidence the overall perception is that epidemiologic studies provide sufficient evidence that obesity is a risk factor for both cancer incidence and mortality.39 Moreover, the evidence supports strong links of obesity with the risk for cancer of the breast (in post-menopausal women) as well as numerous other malignancies.40

Environmental factors

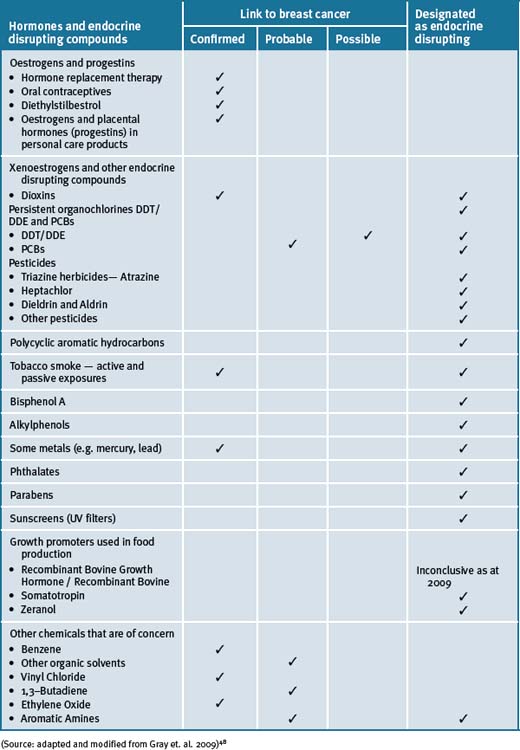

An increasing body of scientific evidence from both human and animal models indicates that exposure of fetuses, young children and adolescents to radiation and or environmental chemicals puts them at considerably higher risk for developing breast cancer in later life.41 These data are consistent with the role of environmental exposures, especially at young ages, in affecting the later incidence of breast cancer in women who have immigrated to relatively industrialised areas from regions of the world with lower risks of breast cancer. There are numerous environmental chemicals that have been associated with breast cancer (see Table 8.2).

The increasing incidence of breast cancer in the decades following World War II paralleled the proliferation of synthetic chemicals. An estimated 80 000 synthetic chemicals have been documented to be in use today in the US, and another 1000 or more are added each year.42 A recent survey indicated that 216 chemicals and radiation sources have been registered by international and national regulatory agencies as being experimentally implicated in breast cancer causation.43, 44 Many of the chemicals (i.e. that include common fuels, solvents and industrial processes) can persist in the environment45 and can accumulate in body fat and may remain in breast tissue for decades.46, 47

Nutritional influences

Soy and phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens present in soy are structurally and functionally similar to oestrogen and have hence received significant attention as potential dietary modifiers of breast cancer risk. A meta-analysis of published studies on soy intake and breast cancer noted a significant protective effect of high soy intake on risk of breast cancer.49 The comparatively high dietary intake of soy in Asian countries has been hypothesised to at least partly explain the lower breast cancer incidence patterns in these countries as compared with the Western world. The hypothesis is however contentious.50, 51

A variety of health benefits, including protection against breast cancer, have been attributed to soy food consumption, primarily because of the soybean isoflavones (genistein, daidzein, glycitein).52 Isoflavones are considered to be possible selective oestrogen receptor modulators but possess non-hormonal properties that also may contribute to their effects.

A recent RCT study did not support the hypothesis however, that soy intake reduced breast cancer risk.53 A diet high in soy protein among post-menopausal women did not decrease mammographic density. A further recent study from Japan supports this notion.54 This prospective study suggested that consumption of soy food had no protective effects against breast cancer and that large-scale investigations eliciting genetic factors may clarify different roles of various soybean-ingredient foods on the risk of breast cancer.

Moreover, no effect on menopausal symptoms was reported in a RCT that investigated oral soy supplements versus placebo for the treatment of menopausal symptoms in patients with early breast cancer.55

It has been proposed though that intake of soy in early life and or in adolescence may be protective for the later development of breast cancer.56 In most Asian countries where the incidence of breast cancer is exceptionally low, soy is consumed 2–3 times daily, and hence it is likely that it is protective.57

Dairy foods

There have been 3 meta-analysis published that have investigated the relationship between dairy food consumption and the risk of breast cancers. The first meta-analysis to combine the results of 5 cohort and 12 case-control studies about dairy product consumption and breast cancer risk found a small increased risk of breast cancer in women with greater intakes of milk.58

In 2002, and forming part of the Pooling Project, a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies was published.59 For this pooled analysis, 8 prospective studies with at least 200 cases of breast cancers each were included, thus bringing a total of 351041 healthy women and 7379 invasive breast cancer cases to the analysis. With respect to dairy products, different food groups were considered. Dairy products were divided into solids (butter and cheese) or liquids (milk, yoghurt, ice cream, etc.). Subgroups were also considered (whole, semi-skimmed or skimmed milk). Thus, ten different subgroups of dairy products were considered. Dairy product intake was analysed as a continuous variable (incrementally of 100g daily consumption for all products except butter and cream, and 10g for cream) and as categorical variable comparing higher versus lower quartiles of consumption. Other dietary and non-dietary factors associated with breast cancer were also considered, such as total energy, alcohol intake, parity, menopausal status and body mass index (BMI; i.e. level of obesity). Women in the 4th quartile of liquid dairy products consumed almost 630g of this kind of dairy product daily, whereas women in the first quartile consumed only 360g daily. No relationship was found between dairy product intake and breast cancer risk, neither treating dairy products as a continuous variable nor treating it as a categorical one. The research did not find statistically significant associations in any of the 10 subgroups of dairy products considered. The analysis concluded that, taking into account data of more than 350 000 women, there was no evidence that a diet rich in dairy products during middle or advanced age could increase or modify the risk of breast cancer in North American or European women.59

A more recent review about consumption of dairy products and risk of breast cancer concluded that published epidemiological data do not provide consistent evidence for an association between the consumption of dairy products and breast cancer risk.60 This study pointed out limitations that must be considered. Namely the moderate reliability of the methods used to assess dairy product intake, which could lead to some misclassifications. Also that consumption of dairy products may be associated with other dietary habits or other variable nutrient content of dairy products (such as vitamin D consumption through food fortifications) that could also influence breast cancer risk.59

Meat consumption

A hypothesis has been advanced that links red meat consumption to the induction of carcinogenesis through it’s highly bio-available iron content, growth-promoting hormones used in animal production, carcinogenic heterocyclic amines formed in cooking, and its specific fatty acid content.61, 62

A meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies reported that there was a modest association of red meat intake with breast cancer incidence,63 but no association was noted in a pooled analysis of prospective studies.64 More recent reports from 2 large prospective cohorts noted an elevated risk with higher red meat consumption. In an analysis of the NHS II (n = 1021 cases that were predominantly pre-menopausal), a positive association between red meat and breast cancer risk was observed, especially for oestrogen receptor-negative and progesterone receptor-positive cancers,65 comparing more than 1.5 servings per day to 3 or fewer servings per week. In the UK Women’s Cohort Study (n = 678 cases), an increased risk of breast cancer was observed among women with a high red meat intake, with a 12% increase in risk per 50g increment of meat each day.66 A study of post-menopausal Danish women (n = 378 cases) showed an elevated risk of breast cancer in those women consuming red meat and processed meat (≥25g per day). This association was confined to women genetically susceptible to carcinogenic aromatic amines due to polymorphisms in N-acetyl transferase.67

Carbohydrates

A number of prospective cohort studies have not shown any consistent associations between total carbohydrate, glycaemic index, glycaemic load, and breast cancer risk, and most results have not been significant.68 However, these findings are not consistent with the association of refined carbohydrates and obesity in Western societies and the link to breast cancer which is opposite to findings in Asian countries (see under ‘Weight control and energy intake’ in this chapter).

Alcohol

Moderate alcohol consumption has been reported to increase sex steroid hormone levels and may interfere with folate metabolism, both of which are potential mechanisms for the observed associations of moderate alcohol intake with several forms of cancer, particularly breast and colorectal.69, 70

A meta-analysis of pooled cohort studies showed that there was a 10% increase in breast cancer risk for every 10g of alcohol consumed per day.71 A similar magnitude of association was noted in 2 pooled analyses.72 A dose-response relationship without a threshold effect has been reported, such that with even 1 drink per day was predictive of a modestly elevated risk for breast cancer.73, 74 Menopausal status and type of alcoholic drink do not seem to modify this association. However, an interaction between folate and alcohol intake suggests that an adequate folate intake (most commonly achieved by taking a multiple vitamin or folate supplement) appears to reduce or eliminate the excess risk due to alcohol consumption.75, 76

A recent descriptive study has reported that alcohol and breast cancer risk may be defined by oestrogen and progesterone receptor status.77 Moreover, the study supported the notion that alcohol was more strongly related to oestrogen positive than to oestrogen negative breast tumours. Furthermore, a further study concluded that although smoking was not related to asynchronous contralateral breast cancer, this study, the largest study of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer to date, demonstrated that alcohol was a risk factor for the disease, as it was for a first primary breast cancer.78

Diets

Mediterranean diet

An early review has pointed out that a number of cancers, such as cancer of the large bowel, breast and other hormonal dependent organs, are less frequent in Mediterranean countries than in northern Europe.79 It has been put forward that a low dietary intake of saturated fat, accompanied by a higher intake of unrefined carbohydrates, and possibly other protective nutrients (phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables) could be the cause of such risk differences.

Recent studies suggested that adherence to a Mediterranean diet may be protective against breast cancer. An Italian study reported that a traditional Mediterranean diet significantly reduced endogenous oestrogen.80 The results of this important study could eventually lead to identifying selected dietary components that more effectively can decrease oestrogen levels and, hence, provide a basis to develop dietary preventive measures for breast cancer. A US study confirms such notions by reporting that in their study, selected dietary patterns (such as those found in the Mediterranean diet) may be protective primarily in the presence of pro-carcinogenic compounds such as those found in tobacco smoke.81

Moreover, Western lifestyles, characterised by reduced physical activity and a diet rich in fat, refined carbohydrates, and animal protein is associated with high prevalence of overweight, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and high plasma levels of several growth factors and sex hormones. Most of these factors are associated with breast cancer risk and, in breast cancer patients, with increased risk of recurrences. Such metabolic and endocrine imbalances can be favourably modified through comprehensive dietary modification, shifting from a Western to Mediterranean and macrobiotic diets.82

Vegetarian diets

A recent study strongly suggests that a diet characterised by a low intake of meat and/or starches and a high intake of legumes is associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer in Asian Americans.83

Further, a recent study investigated the associations of different dietary patterns (Western, Prudent, Native Mexican, Mediterranean, and Dieter) with the risk for breast cancer in Hispanic women (757 cases and 867 controls) and non-Hispanic white women (1524 cases and 1598 controls) from the Four-Corners Breast Cancer Study.84 The results showed that the Western (odds ratio for highest versus lowest quartile) and Prudent dietary patterns were associated with greater risk for breast cancer, and the Native Mexican and Mediterranean dietary patterns were associated with lower risk of breast cancer. Body mass index modified the associations of the Western diet and breast cancer among post-menopausal women and those of the Native Mexican diet among pre-menopausal women. Associations of dietary patterns with breast cancer risk varied by menopausal and body mass index status, but there was little difference in associations between non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women.

It has also been reported that nutrition for primary prevention of breast cancer by dietary means therefore relies on an individually tailored mixed diet, rich in basic foods and traditional manufacturing and cooking methods.85

Nutritional supplements

Multivitamins and/or minerals

The relationship between breast cancer and micronutrients is complex. It includes folate, vitamins, and carotenoids, and has been investigated in large prospective studies using biomarkers of intake. Two recent meta-analyses noted a possible protective effect by folate, especially among women who drank alcohol.86, 87

A recent systematic review of vitamin and mineral supplement use among US adults after cancer diagnosis reported that breast cancer survivors had the highest use.88

A recent double-blinded, randomly controlled, cross-over trial of multivitamins versus placebo in patients with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy was undertaken to evaluate fatigue and quality of life.89 The study results showed that no significant changes were elicited with the use of multivitamins. Hence, multivitamins supplementation did not improve radiation-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer. Moreover, a recent report on multivitamin use and risk of cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) cohorts showed that following a median follow-up of 8.0 and 7.9 years in the clinical trial and observational study cohorts, respectively, the WHI study provided convincing evidence that multivitamin use had no influence on the risk of common cancers, cardiovascular disease (CVD), or total mortality in post-menopausal women.90 However, this study did not include lifestyle factors such as behaviour and exercise and, hence, it is difficult to see how its findings could be conclusive. Moreover, the recent Framingham study found that elevated homocystine was the most important risk factor for CVD which is usually normalised by a multivitamin supplement.91

Vitamin D

Vitamin D, a fat-soluble pro-hormone, is synthesised in response to sunlight. It has been documented that experimental evidence suggests that vitamin D may reduce the risk of cancer through regulation of cellular proliferation and differentiation as well as inhibition of angiogenesis.92

There have been 10 descriptive studies that have investigated the relationship between vitamin D intake and breast cancer risk. Namely, 5 cohort studies 93–97 and 5 case control studies.98–102 Overall, the case control study of Knight et. al.99 examined sunlight exposure and intake of vitamin D-rich foods as well as vitamin D supplements at various ages (10–19, 20–29, 45–54 years). Sun exposure and use of vitamin D supplements or multivitamins between the ages of 10–19 and 20–29 were associated with reduced risk of breast cancer. Of the hospital-based case-control studies, Nunez et. al.96 and the cohort studies of John et. al.,90 Shin et. al.,91 and McCullough et. al.94 provided some evidence for inverse associations, while the results of most of the remaining studies were essentially null.

Vitamins E

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over randomised clinical trial reported a marginal statistical effect of vitamin E (dose used 800IU/day) in the treatment of hot flashes. The treatment duration was for 4 weeks of daily vitamin E consumption and was compared with placebo in 120 breast cancer patients.103 Vitamin E was associated with 1 less hot flash per person per day and did not induce any significant toxicity. A cross-over analysis showed that vitamin E was associated with a minimal decrease in hot flashes. There was no preference for use of vitamin E over placebo when participants were assessed at the end of the study. The study hence suggested that vitamin E at a dose of 800IU daily can be used because it is inexpensive and non-toxic and it might result in a slightly better relief of hot flashes than placebo. The scientific evidence is therefore limited. Thus, more clinical data are warranted and caution is advocated as vitamin E is not registered for this use. However, these studies did not elucidate whether the synthetic or the natural form of vitamin E was used and hence the conclusions reached may be controversial.

Vitamin A and/or vitamin a-analogs

Studies on specific carotenoid intake and breast cancer risk modulation are limited.104 The roles that carotenoids, retinol, and tocopherols may have in breast cancer aetiology remain complex and largely inconclusive.105 It has been suggested though that consumption of fruits and vegetables high in specific carotenoids and vitamins may be the best option that could reduce pre-menopausal breast cancer risk.101, 106 Recently the relationship between plasma carotenoids at enrolment and 1, 2 or 3, 4 and 6 years and breast cancer-free survival in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study participants (N = 3043), who had been diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, concluded that higher biological exposure to carotenoids, when assessed over the timeframe of the study, was associated with greater likelihood of breast cancer-free survival regardless of study group assignment.107

An early study administered vitamin A to randomly allocated patients (n = 100) with metastatic breast carcinoma treated by chemotherapy.108 The daily doses employed indefinitely ranged from 350 000 to 500 000IU according to body weight. There was noted a significant increase in the complete response rate. When subgroups determined by menopausal status were considered in the analysis of the data, it was observed that serum retinol levels were only significantly increased in the post-menopausal group on high dose Vitamin A. Response rates, duration of response and projected survival were only significantly increased in this subgroup.

Chemotherapy, which is fundamental for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, is reported to rarely cure due to the presence of minimal residual disease that has spread to other organs. A pilot study was designed to test whether vitamin A (as retinyl palmitate) in combination with interferon and tamoxifen could improve overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients.109 The results showed that the combination was feasible and showed activity in metastatic breast cancer with an acceptable level of toxicity.

Preclinical models suggest that synthetic retinoids can inhibit mammary carcinogenesis.110 In a recent review of clinical trials with synthetic retinoids for breast cancer chemo prevention it was reported that a phase III breast cancer prevention trial, investigating fenretinide (a synthetic retinoid derivative of vitamin A), showed a durable trend to a reduction of second breast malignancies in pre-menopausal women. This pattern was associated with a favourable modulation of circulating IGF-I and its main binding protein IGFBP-3, which have been associated with breast cancer risk in pre-menopausal women in different prospective studies.111 Moreover, a recent study showed that fenretinide positively balanced the metabolic profile in overweight pre-menopausal women at high risk for breast cancer, and this was postulated to perhaps favourably affect breast cancer risk.112

All trans retinoic acid (ATRA) (also known as Tretinoin) is the acid form of vitamin A. A phase II trial employed all trans retinoic acid so as to evaluate its tumour cytoreduction in patients with metastatic breast cancer and to characterise the initial pharmacokinetics of the compound.113 The study concluded that ATRA did not have any significant activity in patients with hormone refractory metastatic breast cancer.

A phase I–phase II combination clinical trial with tamoxifen and ATRA in patients with advanced breast cancer investigated their additive antitumor effects.114 The study showed that declines in serum IGF-I concentrations observed in patients treated with tamoxifen and ATRA were similar to those observed in patients treated with tamoxifen alone. Additional studies are warranted to further investigate these data.

Lycopene

The epidemiologic literature regarding intake of tomatoes and tomato-based products and blood lycopene (a compound derived predominantly from tomatoes) level in relation to the risk of various cancers was reviewed. The outcome suggested strongly that there was a consistently lower risk of cancer for a variety of anatomic sites (including breast) that was associated with higher consumption of tomatoes and tomato-based products adding further support for current dietary recommendations to increase fruit and vegetable consumptions.115

A recent review concluded that the emerging area of health-derived benefits from food sources such as lycopene requires additional investigations into its effects on breast cancer.116

Integrative management of malignant breast disease

Lifestyle

Breast cancer can spread insidiously. The prevalence in the US during the years 2000–2004 in women aged 20–24 years had the lowest breast cancer incidence rate of 1.4 cases per 100 000 women, and women aged 75–79 years had the highest incidence rate of 464.8 cases per 100 000. The decrease in age-specific incidence rates that occurs in women aged 80 years and older may reflect lower rates of screening, the detection of cancers by mammography before age 80, and incomplete detection.117

An early investigation of approximately 25 000 women diagnosed with breast cancers reported that at diagnosis, 5–15% of patients had metastatic disease and almost 40% had regional spread of the disease.118

Promotion of behaviour patterns that optimise energy balance (i.e. weight control and increasing physical activity) may be viable options for the prevention of breast cancer. Researchers from the US and Peoples Republic of China (PRC) have evaluated the hypothesis that a pattern of behavioural exposures indicating positive energy balance (i.e. less physical activity/sport activity, high BMI, or high energy food intake) would be associated with an increased risk for breast cancer in the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study.119 This population-based study comprised 1459 incident breast cancer cases and 1556 age frequency-matched controls. Participants completed in-person interviews that collected information on breast cancer risk factors, usual dietary intake and physical activity in adulthood. Anthropometric indices were also measured. The study concluded that lack of physical activity/sport activity, low occupational activity, and high BMI were all individually associated with an increased risk for breast cancer (odds ratios [OR] 1.49 to 1.86).

A recent study has summarised that lifestyle changes including continuous or intermittent energy restriction and/or physical activity may be significantly beneficial for preventing breast cancer.120

Mind–body medicine

Cancer is a profoundly stressful experience. A cancer diagnosis is full of trepidation by most people because of its life-threatening implications and the potentially serious side-effects of the treatments. Hence, mind–body therapies have become more popular within cancer populations as methods to treat physical and psychiatric symptoms in conjunction with conventional allopathic care. Interventions such as support groups, educational programs, guided imagery, and expressive writing have been studied and are now frequently incorporated into plans of care for all types of cancer patients.121, 122, 123

Psychotherapeutic and social support interventions provide emotional and other psychological benefits to cancer patients.124 Group, individual and family interventions have been shown to reduce depression and anxiety, improve coping and mobilise social support.125, 126 However, what is more controversial are findings that psychosocial interventions may affect the course of the disease as well as the adjustment to it. Most people are ready to accept that changes in physical status influence cognition and affect.127 In the context of a holistic approach to health that includes the concept of unity of mind and body, it makes sense that intervention at a mental level might have physical consequences.128

Research by a number of investigators has reported that patients who underwent psychological intervention lived longer than the national average.129–132 Some researchers have analysed the psychological attributes associated with patients who survive what is thought to be terminal cancer. Roud133 noted that all long-term survivors believed that there was a direct relationship between the outcomes experienced and their psychological states. They remained confident that they would not die, and felt that these positive expectations were critical to the healing process. They assumed responsibility for all aspects of their lives, including recovery and established relationships with physicians described as trusting, meaningful, and healing.

The key components of effective interventions appear to be:

These interventions help cancer patients prepare for the worst but hope for the best. All have the goal of living better, and improve prognosis.

Mindfulness meditation

Mindfulness meditation is a form of mind–body therapy that is gaining credibility and interest for use in oncology patients.135 It has been reported that the primary emphasis of mindfulness meditation is experiencing life fully and being in touch with the full range of human emotions and sensory experiences. Rather than a method to control or change unpleasant or unwanted emotions, thoughts, or sensations, mindfulness meditation is a way of being engaged in the complete experience of what is happening in the present moment without getting entangled in reflections about previous experiences or an anticipated future.136, 137 Mindfulness meditation will often elicit relaxation, and as a result, offers individuals a way to alleviate suffering that often accompanies pain or emotional discomfort.138

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

MBSR is a well-defined, systematic, educational, patient-focused intervention with formal training in mindfulness meditation and its applications in everyday life, which includes managing physical and emotional pain for cancer patients.136

A recent study demonstrated that MBSR is a significantly effective program that is feasible for women recently diagnosed with early stage breast cancer and the results provided preliminary evidence for beneficial effects of MBSR on immune function, quality of life and coping.139 A further study utilising MBSR to investigate a 1-year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes demonstrated that MBSR program participation was associated with enhanced quality of life and decreased stress symptoms, altered cortisol and immune patterns.140 These results were consistent with less stress and mood disturbances, and decreased blood pressure. The pilot data represented a preliminary investigation of the longer-term relationships between MBSR program participation and a range of potentially important biomarkers in patients with breast cancer.

Overall recent reviews conclude that from all the current available scientific evidence, MBSR may be a potentially beneficial intervention.141, 142 Moreover, a recent clinician’s guide to MBSR concluded that it was a safe, effective, integrative approach for reducing stress. Also both patients and health care providers experiencing stress or stress-related symptoms may benefit from MBSR programs.143 MBSR interventions can be safely and effectively used in a variety of patient populations.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

CBT was found to be helpful for survivors of breast cancer who reported cognitive impairment after chemotherapy in a single-arm pilot study.144 Ferguson et. al. reported that a specialised intervention using CBT principles called ‘memory and attention adaptation training’ was delivered to 29 survivors of breast cancer. The study concluded that participants reported high treatment satisfaction and rated the memory and attention adaptation training as helpful in improving ability to compensate for memory problems. Given these results, the CBT treatment appears to be a feasible and practical cognitive behaviour program that necessitates continued evaluation among cancer survivors who experience persistent cognitive dysfunction.

Few studies have examined the experience of cognitive impairment and how it affects day-to-day life. A small interview-based study with 10 survivors of breast cancer who reported cognitive impairment after chemotherapy showed that the women who reported the most disruption from cognitive impairment were those with high-stress occupations and coping with professional and family commitments.145

A recent Cochrane review that assessed the effects of psychological interventions (educational, individual cognitive behavioural, psychotherapeutic, or group support) on psychological and survival outcomes for women with metastatic breast cancer reported that there was insufficient evidence to advocate that group psychological therapies be recommended to women with metastatic breast cancer.146 However, this review did not analyse the results of other studies that showed benefit for psychological therapies.147

Hypnosis

A recent review has investigated the potential use of hypnosis in reducing the frequency and intensity of hot flashes in women with breast cancer.148 The study concluded that hypnosis may be a preferred treatment because of the few side-effects it elicits and the preference of many women for a non-hormonal therapy. Two recent randomised trials have confirmed this notion.149, 150

In the first study, 60 female breast cancer survivors with hot flashes were randomly assigned to receive hypnosis intervention (5-weekly sessions) or no treatment.147 The study concluded that hypnosis appeared to reduce perceived hot flashes in breast cancer survivors and may have additional benefits, such as reduced anxiety and depression, and improved sleep. In the second trial 150 women with primary breast cancer who experienced hot flashes were randomised to either the intervention group, who received a single relaxation training session and were instructed to use practice tapes on a daily basis at home for 1 month, or to the control group who received no intervention.43 This study concluded that relaxation may be a useful component of a program of measures to relieve hot flashes in women with primary breast cancer.

Environment

Studies have investigated the combined effects of 11 different environmental contaminants — all added at levels so low that they did not have any effects in isolation — and found the various chemicals had additive effects with each other and also with naturally occurring oestradiol.151 Likewise, at concentrations found in the environment, the ubiquitous plasticiser bisphenol A has been reported to significantly increase the effects of oestradiol.152 These combined experimental results show that even at low concentrations, environmental chemicals may exacerbate some of the biological effects of natural oestrogens.

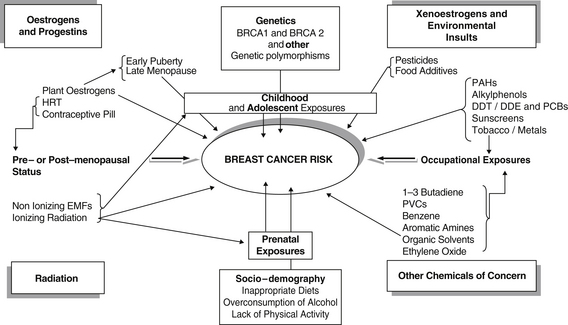

Recent large clinical studies of women with breast cancer have investigated the effects of exposures to environmental chemicals and radiation in combination with other factors. The data from these studies illustrate how complex the interactions among breast cancer risk factors may be (Figure 8.1). The data also help clarify why large epidemiological studies examining the effects of different chemicals on breast cancer risk in women may have contradictory results.

In a study examining the possible link between organochlorin pesticide residues and breast cancer among African American and white women in North Carolina, higher blood (plasma) levels of the chemicals did not match to a diagnosis of breast cancer.153 However, the data did suggest that race/ethnicity, body mass, reproductive history and social factors might make some women more susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of the organochlorin pesticides. Several other studies suggest that specific combinations of genes may make some women more susceptible to specific environmental carcinogens.150, 154, 155

Physical activity

Physical activity is a critical component of energy balance. The daily adherence to physical activity has a significant impact on preventing chronic diseases such as cancer.156 Moreover, current reports clearly support the beneficial role that physical activity and exercise play in reducing the risk for developing breast cancer and preventing or attenuating disease and treatment-related impairments.157

A recent systematic review has reported on 9 randomised clinical trials and the effects of exercise on quality of life in women living with breast cancer.158 The systematic review reported that there was strong evidence that exercise positively influences quality of life in women living with breast cancer. Moreover, a large study with a follow-up of 18 years reported that women who participated in physical activity had half the chance of death as compared with those that did not exercise.159

Adherence to a physical activity program may have additional benefits for women undergoing conventional treatments for breast cancer. A recent small placebo-controlled RCT demonstrated that an exercise intervention administered to breast cancer patients undergoing medical treatment assisted in the alleviation of some treatment side-effects, including decreased total caloric intake, increased fatigue, and negative changes in body composition.160

Recently it was reported in a systematic review that IGF-I and IGFBP-3, can modulate cell growth and survival, and are thought to have important attributes in tumour development.161 The adherence to a prudent physical activity regime may extend survival from cancer through interactions with the IGF–1 axis and in particular IGFBP-3.

A recent RCT demonstrated that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking, decreased IGF-I and IGFBP-3. The exercise-induced decreases in IGF may mediate the observed association between higher levels of physical activity and improved survival in women diagnosed with breast cancer.162 A further study did not support a protective effect of physical activity on breast cancer recurrence or mortality but did suggest that the regular implementation of physical activity was beneficial for breast cancer survivors in terms of total mortality.163

Recently in a study of physical activity and post-menopausal breast cancer patients, it was concluded that only BMI and oestrone were convincingly associated with both post-menopausal breast cancer risk and physical activity. However, it was also reported that aetiologic studies should consider interactions among biomarkers, whereas exercise trials should explore exercise effects independently of weight loss, different exercise prescriptions, and effects on central adiposity.164

Overall, the scientific data is strong for the protective effects associated with physical activity. A study that investigated the associations between recreational physical activity and quality of life in a multiethnic cohort of breast cancer survivors, specifically testing whether associations are consistent across racial and/or ethnic groups after accounting for relevant medical and demographic factors that might explain disparities in quality of life outcomes, showed that meeting recommended levels of physical activity is associated with improved quality of life in non-Hispanic white and black breast cancer survivors.165 These findings may help support future interventions among breast cancer survivors and promote supportive care that includes physical activity.

Yoga

There are not many studies on the efficacy of yoga in women with breast cancer.

Two recent trials have demonstrated benefit in women with breast cancer in abrogating disease and treatment side-effects. The earlier pilot study showed that a home-based yoga program provided participants with significantly lower levels of pain and fatigue, and higher levels of invigoration, acceptance, and relaxation.166 The more recent study, a small RCT carried out by the same research group also showed that women with breast cancer that participated in yoga experienced significantly lower levels of pain and fatigue, and higher levels of invigoration, acceptance, and relaxation.167

Tai chi

There are few studies investigating the efficacy of tai chi as an adjunct intervention in patients with breast cancer as treatment for breast cancer produces side-effects that diminish functional capacity and quality of life. Three studies from the same research group has reported that tai chi can be beneficial and may enhance functional capacity and quality of life among breast cancer survivors.168, 169, 170

However, a recent systematic review has concluded that there is not enough evidence to recommend it as a useful adjunct intervention for women with breast cancer.171

Nutrition

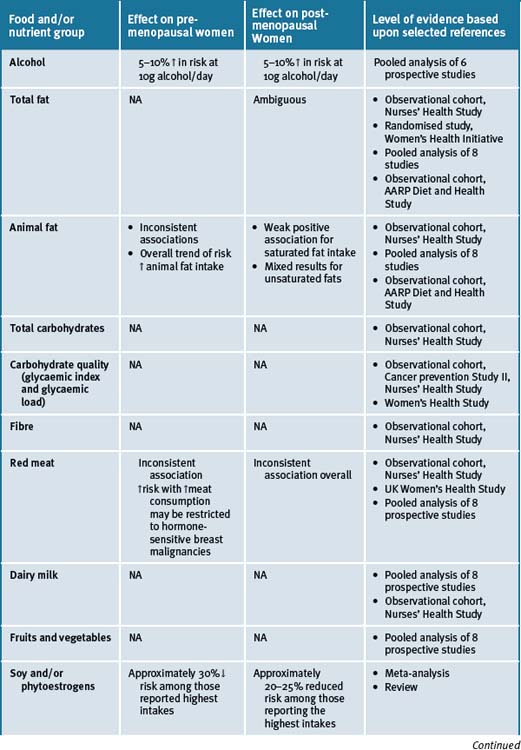

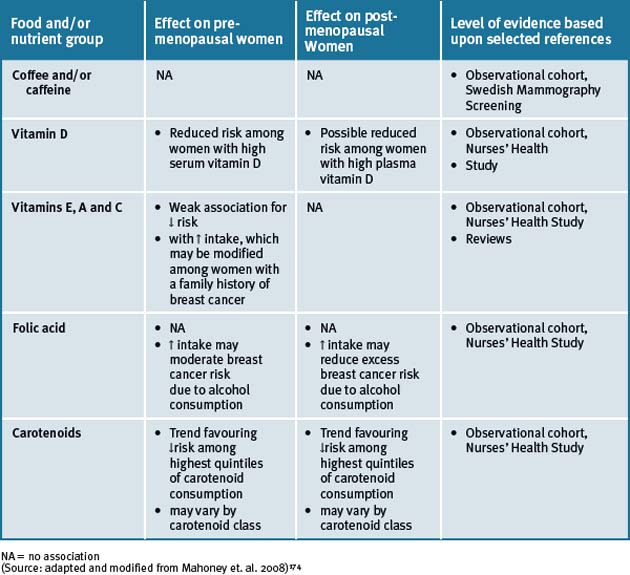

Epidemiological studies show that populations which consume a typical Asian diet have lower incidences of a number of cancers, including breast cancer, than those consuming a Western diet.172 The Asian diet includes mostly plant foods, including legumes, fruits, and vegetables, and is low in fat. The Japanese have the highest consumption of soy foods. The typical Western diet includes large amounts of animal foods, is lower in fibre and complex carbohydrates, and is high in fat. Soy foods are dietary staples in Asia, but are not commonly included in the Western diet.173 The epidemiological data reports that there are a number of food groups that have an association with breast cancer risk in both pre- and post-menopausal women and an overview is presented in Table 8.3.

Dietary fat

The relationship between saturated fat consumption and breast cancer incidence and survival remains controversial. Early descriptive studies have reported that the 5-year survival of women with breast cancer in Tokyo, where dietary fat intake is low, was about 15% greater than that of women from Western countries.175, 176, 177 A recent study supported this premise.178 However, additional recent studies do not support this concept.179, 180

The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study was a large, multi-institutional, randomised trial designed to test if noticeably increasing the consumption of vegetables, fruit, fibre and carotenoids and with concomitant decreases in total and saturated fat consumption (a study design as a putative cancer-preventive dietary guide) would lower the risk of breast cancer events such as recurrences and new primaries for women who had been recently diagnosed (within 4 years of diagnosis) with early-stage breast cancer.181 The recent WHEL report concluded that the difference between study groups of the RECT was significant only in upper baseline quartiles of intake of vegetables, fruit, and fibre and in the lowest quartile of fat. A significant trend for fewer breast cancer events was observed across quartiles of vegetable, fruit and fibre consumption.182

Together with previously reported efficacy results, the WHEL study data suggests that a lifestyle intervention that reduces dietary fat intake and is associated with modest weight loss may favourably influence breast cancer recurrence.183, 184 The WHEL low-fat eating plan can serve as a model for implementing long-term dietary interventions in clinical practice.

Herbal medicines

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

Despite a quite extensive series of laboratory investigations detailing many biological effects of herbal medicine compounds, there are only a few clinical trials that have been completed to test specific hypotheses regarding the mode of action of TCM.185

Juzentaiho–to is a mixture of extracts from 10 medicinal herbs and has been used traditionally to treat patients with anaemia, anorexia or fatigue.186 An early RCT study from Japan demonstrated that Juzentaiho–to supportive therapy improved quality of life in patients with advanced breast cancer.187

Immuno-stimulating polysaccharides extracted from the Chinese medicinal plant Yun Zhi (Coriolus versicolor) have been found to enhance various immunological functions, and Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) to show beneficial effects on the circulatory system.188 A recent study has demonstrated that the regular oral consumption of Yunzhi–Danshen capsules could be beneficial for promoting immunological function in post-treatment of breast cancer patients.189

A recent double-blind RCT of a Chinese herbal medicine as complementary therapy for reduction of chemotherapy-induced toxicity reported that the TCM did not reduce the hematologic toxicity associated with chemotherapy. However, supplementally the TCM did have a significant impact on control of nausea.190 The herbs in this study consisted of 225 types of the commonly used herbs stocked in packaged form. Each package contained 3–10g of water-soluble herbal granules (see: http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/18/4/768).191

Ruyiping is a TCM compound/herbal medicine composed of 5 Chinese herbs for removing toxic materials and dissipating nodules from Runing II, another traditional Chinese compound/herbal medicine for treating breast cancer, and in preventing recidivation and metastasis in breast cancer patients post surgery. The effect of Ruyiping in preventing recidivation and metastasis was similar to that of Runing II.192 Ruyiping is reported as being the essential component of Runing II for preventing recidivation and metastasis. The result provides some clinical evidence for the theory that Yudu Pangcuan (vestigial poison invasion elsewhere) is the essential pathogenesis of breast cancer’s recidivation and metastasis and the utilisation of Sanjie Jiedu (dispersing accumulation and detoxification) is the important therapeutic principle in preventing recidivation and metastasis after breast cancer surgery.

The TCM Shenqi Fuzheng (radix ginseng rubra; radix aconiti lateralis preparata) has traditional immune enhancement activity.193 A study investigating Shenqi Fuzheng injections in combination with chemotherapy in treating metastatic cancer could reduce the occurrence of adverse reactions to chemotherapy, improve clinical symptoms, elevate quality of life and enhance immunity in patients with metastatic disease.194

In a further study investigating the treatment of advanced breast cancer, Shenqi Fuzheng injections alleviated the bone marrow inhibition caused by chemotherapy, improved clinical symptoms and quality of life and prolonged the survival period by regulating cellular immune function of the patients, so as to enhance the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy.195

A recent randomised phase II study using mitomycin/cisplatin regimen with or without Kanglaite (a TCM extracted from a tropical Asian grass called Coix) as salvage treatment was conducted to exploit the herb’s potential effects on patients with advanced breast cancer.196 The study reported no additional benefit when the TCM herb was added to the regimen doublet in the management of advanced breast cancer.

A recent systematic Cochrane review does not support the use of TCM herbs in the management of breast cancer patients.197 This review provides limited evidence of the effectiveness and safety of TCM medicinal herbs in alleviating chemotherapy induced short-term side-effects. TCM medicinal herbs, when used together with chemotherapy, may offer some benefit to breast cancer patients in terms of bone marrow improvement and quality of life, but the evidence is very limited to make any confident conclusions. The requisite is for well-designed clinical trials before any conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness and safety of TCM in the management of breast cancer patients.

Other herbs

There are a number of herbal therapies available for the management of hot flashes in women without breast cancer (see Chapter 25, menopause) that could be useful for those women diagnosed with breast cancer. In this section we have included only those published studies that were specifically investigating the efficacy of herbal remedies in patients diagnosed with breast cancer.

Black cohosh

A study with black cohosh was not significantly more efficacious than placebo against most menopausal symptoms, including number and intensity of hot flashes.198 However, a more recent study with a preparation of black cohosh designated as CR BNO 1055 reported that the combined administration of tamoxifen plus CR BNO 1055 for a period of 12 months allowed satisfactory reduction in the number and severity of hot flushes.199

Femal

A RCT investigating Femal, a herbal remedy elaborated from pollen extracts, demonstrated that the pollen extract significantly reduced hot flushes and certain other menopausal symptoms when compared to placebo.200 Hence this may be useful in breast cancer patients with this symptom.

Ginseng

The scientific literature suggests that fatigue is commonly reported by women during and after breast cancer treatment, where treatment options are often limited. A small 8-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the feasibility of a larger clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of ginseng for treating breast cancer-related fatigue.201 The study encountered numerous methodological problems, which made efficacy reporting impossible to assess. There is a literature though that stipulates that ginseng is widely used in Asian countries as a tonic to increase energy.202

Green and/or black tea polyphenols

Experimental studies have shown that tea and tea polyphenols have anti-carcinogenic properties against breast cancer.203 A number of epidemiologic studies, both case-control and cohort in design, have examined the possible association between tea intake and breast cancer development in humans.204, 205, 206

Recent meta-analytic systematic reviews reporting on the current epidemiologic literature supports the hypothesis that green tea protects against breast cancer.207, 208 Given the relative paucity of human data, prospective cohort studies with a wide range of green tea exposure and longer duration of follow-up are needed to affirm the protective effect of green tea on human breast cancer development. Current epidemiological data do not support a role for black tea in protection against breast cancer in humans. Cohort studies with longer duration of follow-up are also needed to elucidate the effect of black tea on different stages of breast cancer development. Since genetic intertwined with lifestyle and/or dietary cofactors could influence the effect of green and/or black tea on breast carcinogenesis additional studies may have to address the possible interaction effects between tea and other dietary and/or genetic cofactors.209, 210

Aloe vera

Erythema is an effect produced by radiotherapy treatment in breast cancer patients. A recent trial investigating aloe vera for the amelioration of erythema in radiotherapy-treated patients with breast cancer, included 50 women who were selected consecutively to participate in the study.211 All of the participants were subjected to treatment with high-energy electrons (9–20 MeV) after mastectomy, 2 Gy per day to a total dose of 50 Gy. Measurements were performed before the start of radiotherapy and thereafter once a week during the course of treatment. Aloe vera and Essex lotion were applied twice every radiation day in selected sites. The study concluded that there was no additional benefit with the use of aloe vera. An earlier phase III study also concluded that an aloe vera gel did not significantly reduce radiation-induced skin side-effects.212 However, an aqueous cream was useful in reducing dry desquamation and pain related to radiation therapy.

Other supplements

Omega-3 fatty acids (n-3 FA)

A review that examined the scientific evidence on biological mechanisms which may be involved in the inhibition of mammary carcinogenesis by long-chain n-3 FAs, focused on an apoptotic effect by its lipid peroxidation products. It viewed dietary supplements of fish oil rich in n-3 FA as viable alternative supplements for pre-menopausal women over the age of 40 years who are shown to be at increased breast cancer risk.213 A recent review that investigated a large body of literature spanning numerous cohorts from many countries and with different demographic characteristics does not provide evidence to suggest a significant association between omega-3 fatty acids and cancer incidence. The review concluded that dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids was unlikely to prevent cancer.214

Some potential mechanisms for the activity of n-3 fatty acids against cancer include modulation of eicosanoid production and inflammation, angiogenesis, proliferation, susceptibility for apoptosis, and oestrogen signalling. In humans, n-3 PUFA have also been used to suppress cancer-associated cachexia and to improve the quality of life. Moreover, the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs, such as doxorubicin, epirubicin and tamoxifen, and radiation therapy has been improved when the diet included n-3 PUFA.215 A current recommendation is that cancer patients supplement with n-3 fatty acids EPA/DHA at a dose of 8–10 g/day, with good results observed consistently concerning body-weight maintenance, immune function and appetite.216

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

Acupuncture has been studied in breast cancer patients primarily with the intention of reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, menopausal symptoms and pain perception.217, 218, 219 Investigational data supports the efficacy of acupuncture for cancer-related pain220 and reducing the frequency of vomiting.221 These effects, however, were of limited duration.

A review on CAM modalities concludes, though, that the available data on CAMs that includes acupuncture in the treatment of early-stage breast cancer does not support their application.222

A small trial with 38 post-menopausal breast cancer patients who were treated for 12 weeks with electro-acupuncture, reported reducing hot flashes significantly.223

There is an emerging consensus that between one-fifth and one-half of breast cancer patients experience chemotherapy-associated cognitive dysfunction.224 Research shows that patients with cancer are often interested in acupuncture for symptom relief. It has been suggested that a skilled practitioner could use acupuncture to relieve a substantial variety of chemotherapy-induced side-effects, including pain, fatigue, nausea and/or vomiting, xerostomia, and mood disorders.225 A recent review supports this notion.226 There is evidence that acupuncture may be effectively used to manage a range of psychoneurological issues in breast cancer patients, some of which are similar to those experienced by patients with chemotherapy-associated cognitive dysfunction.

Massage therapy

Massage therapy in combination with aromatherapy has been shown to be beneficial for cancer patients in the management of disease and treatment-related symptoms.227

A Cochrane review investigated only 3 studies involving 150 randomised patients. Since none studied the same intervention it was not possible to combine the data. In summary the review documented the following:228

A recent nursing review reported on the various approaches for treating lymphoedema that included skin care, elevation of the affected arm, the use of compression hosiery, multi-layer bandaging, massage (manual lymphatic drainage), and surgery.229 Bandage plus hosiery, massage and compression hosiery were concluded to be effective.

Conclusion

Three decades of intensive experimental and clinical research on cancer prevention have yielded an impressive body of scientific knowledge about cancer epidemiology, causation, and preventative measures. The complexity of the aetiology of breast cancer is significant though (see Figure 8.1, page 178).

Despite our increased understanding in these critical areas, this knowledge is not being translated adequately into initiatives that will impact upon public health. The recent release of the World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research report on diet and lifestyle strategies for cancer prevention — grounded in an evidence-based systematic review of the published literature — is a strong acknowledgment of the benefits of a lifestyle approach to reduce cancer risk.230

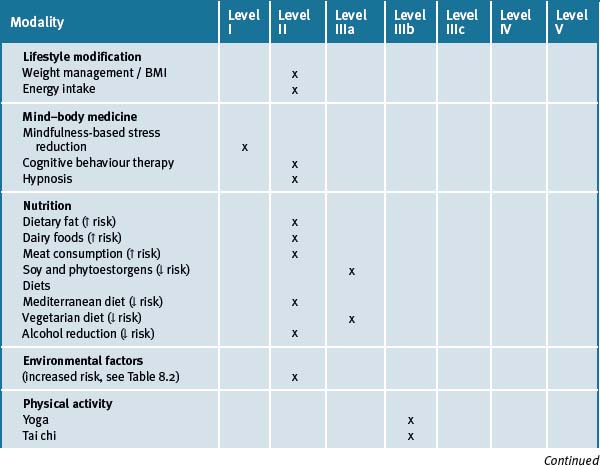

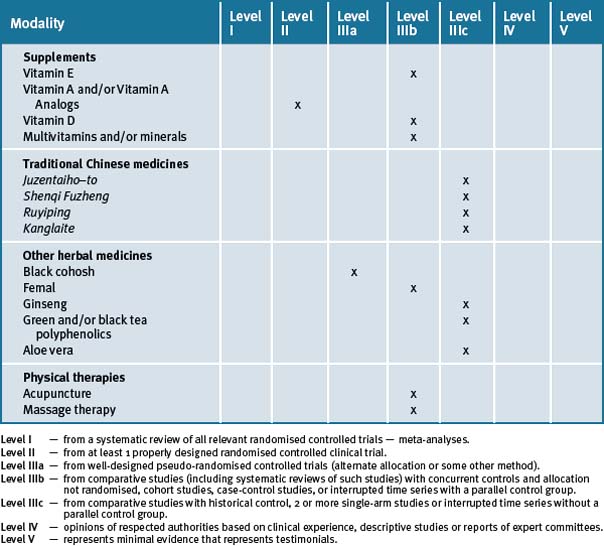

The risk of breast cancer can be reduced by avoidance of weight gain in adulthood and limiting the consumption of alcohol and adherence to a more prudent diet consisting of fish, vegetables and fruit daily, along with physical activity. Table 8.4 summarises the current evidence for CM treatments.

Clinical tips handout for patients — breast disease

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine (most helpful)

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Vitamins and minerals

Multivitamin/mineral

Vitamin D3

Children at risk: 200–400IU daily under medical supervision.

Pregnant and lactating women at risk: under medical supervision.

Vitamin C

Natural vitamin E

Herbal medicines

Evening primrose oil (Oenothera biennis)

1 London S.J., Connolly J.L., Schnitt S.J., et al. A prospective study of benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 1992;267:941-944.

2 Pfeifer J.D., Barr R.J., Wick M.R. Ectopic breast tissue and breast-like sweat gland metaplasias: an overlapping spectrum of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:190-196.

3 McDivitt R.W., Stevens J.A., Lee N.C., et al. Histologic types of benign breast disease and the risk for breast cancer. Cancer. 1992;69:1408-1414.

4 Guray M., Sahin A.A. Benign breast diseases: classification, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11(5):435-449.

5 Sarnelli R., Squartini F. Fibrocystic condition and “at risk” lesions in asymptomatic breasts: a morphologic study of post-menopausal women. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1991;18:271-279.

6 Fitzgibbons P.L., Henson D.E., Hutter R.V. Benign breast changes and the risk for subsequent breast cancer: an update of the 1985 consensus statement. Cancer Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:1053-1055.

7 Kelsey J.L., Gammon M.D. Epidemiology of breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1990;12:228-240.

8 Meisner A.L., Fekrazad M.H., Royce M.E. Breast disease: benign and malignant. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(5):1115-1141.

9 Marshall J.M., Graham S., Swanson M. Caffeine consumption and benign breast disease: a case-control comparison. Am J Publ Health. 1982;72(6):610-612.

10 Lubin F., Ron E., Wax Y., et al. A case-control study of caffeine and methylxanthines in benign breast disease. JAMA. 1985;253(16):2388-2392.

11 Boyle C.A., Berkowitz G.S., LiVoisi V.A., et al. Caffeine consumption and fibrocystic breast disease: a case-control epidemiologic study. JNCI. 1984;72:1015-1019.

12 Vecchia C., Franceschi S., Parazzini F., et al. Benign breast disease and consumption of beverages containing methylxanthines. JNCI. 1985;74:995-1000.

13 Ernster V.L., Mason L., Goodson W.H., et al. Effects of a caffeine-free diet on benign breast disease: a randomised trial. Surgery. 1982;91:263.

14 Allen S., Froberg D.G. The effect of decreased caffeine consumption on benign proliferative breast disease: a randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1987;101:720-730.

15 Minton J.P., Foecking M.K., Webster D.J.T., et al. Caffeine, cyclic nucleotides, and breast disease. Surgery. 1979;86:105-108.

16 Minton J.P., Abou-Issa H., Reiches N., et al. Clinical and biochemical studies on methylxanthine-related fibrocystic breast disease. Surgery. 1981;90:299-304.

17 Rose D.P., Boyar A.P., Cohen C., et al. Effect of a low-fat diet on hormone levels in women with cystic breast disease. I. Serum steroids and gonadotropins. JNCI. 1987;78:623-626.

18 Woods M.N., Gorbach S., Longcope C., et al. Low-fat, high-fiber diet and serum estrone sulfate in pre-menopausal women. AJCN. 1989;49:1179-1183.

19 Rose D.P., Boyar A., Haley N., et al. Low fat diet in fibrocystic disease of the breast with cyclic mastalgia: a feasibility study. AJCN. 1985;41(4):856. (abstract)

20 Boyd N.F., McGuire V., Shannon P., et al. Effect of a low-fat high-carbohydrate diet on symptoms of cyclical mastopathy. Lancet. 1988;ii:128-132.

21 Lubin F., Wax Y., Ron E., et al. Nutritional factors associated with benign breast disease etiology: a case-control study. AJCN. 1989;50:551-556.

22 Rohan T.E., Negassa A., Caan B., et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of benign proliferative breast disease: a randomized, controlled dietary modification trial. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1(4):275-284.

23 Mansel R.E., Harrison B.J., Melhuish J., et al. A randomized trial of dietary intervention with essential fatty acids in patients with categorized cysts. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;586:288-294.

24 Gateley C.A., Maddox P.R., Pritchard G.A., et al. Plasma fatty acid profiles in benign breast disorders. Br J Surg. 1992;79:407-409.

25 Harding C., Harvey J., Kirkman R., et al. Hormone replacement therapyinduced mastalgia responds to evening primrose oil. Br J Surg. 83(Suppl 1), 1996. 24 (abstract # Breast 012)

26 Pye J.K., Mansel R.E., Hughes L.E. Clinical experience of drug treatments for mastalgia. Lancet. 1985;ii:373-377.

27 Abrams A.A. Use of vitamin E in chronic cystic mastitis. NEJM. 1965;272(20):1080-1081.

28 London R.S., Sundaram G.S., Schultz M., et al. Endocrine parameters and alpha-tocopherol therapy of patients with mammary dysplasia. Cancer Res. 1981;41:3811-3813.

29 Ernster V.L., Goodson W.H., Hunt T.K., et al. Vitamin E and benign breast “disease”: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1985;97:490-494.

30 London R.S., Sundaram G.S., Murphy L., et al. The effect of vitamin E on mammary dysplasia: a double-blind study. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:104-106.

31 Brush M.G., Perry M. Pyridoxine and the premenstrual syndrome. Lancet. 1985;i:1399.

32 Smallwood J., Ah-Kye D., Taylor I. Vitamin B6 in the treatment of pre-menstrual mastalgia. Br J Clin Pract. 1986;40:532-533.

33 Krouse T.B., Eskin B.A., Mobini J. Age-related changes resembling fibrocystic disease in iodine-blocked rat breasts. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1979;103:631-634.

34 Halaška M., Beles P., Gorkow C., et al. Treatment of cyclical mastalgia with a solution containing Vitex agnus extract: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind study. The Breast. 1999;8:175-181.

35 Böhnert K.J. The use of Vitex agnus castus for hyperprolactinemia. Quar Rev Nat Med. 1997;Sprg:19-21.

36 Chang S.C., Ziegler R.G., Dunn B., et al. Association of energy intake and energy balance with post-menopausal breast cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):334-341.

37 Silvera S.A., Jain M., Howe G.R., et al. Energy balance and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97(1):97-106.

38 Harvie M., Howell A. Energy balance adiposity and breast cancer – energy restriction strategies for breast cancer prevention. Obes Rev. 2006;7(1):33-47.

39 Fair A.M., Montgomery K. Energy balance, physical activity, and cancer risk. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:57-88.

40 Pan S.Y., DesMeules M. Energy intake, physical activity, energy balance, and cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:191-215.

41 Birnbaum L.S., Fenton S.E. Cancer and developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors. Environ Health Persp. 2003;111:389-394.

42 Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics. Overview: Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics Programs (Internet) 2007. www.epa.gov/oppt/pubs/oppt101c2.pdf (accessed 12 April 2009)

43 Brody J.G., Moysich K.B., Humblet O., et al. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2007;109(Suppl 12):2667-2711.

44 Rudel R.A., Attfield K.A., Schifano J.N., Brody J.G. Chemicals causing mammary gland tumors in animals signal new directions for epidemiology, chemicals testing, and risk assessment for breast cancer prevention. Cancer. 2007;109(Suppl 12):2635-2666.

45 Rudel R.A., Camann D.E., Spengler J.D., et al. Phthalates, alkylphenols, pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds in air and dust. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:4543-4553.

46 Siddiqui M.K., Anand M., Mehrotra P.K., et al. Biomonitoring of organochlorines in women with benign and malignant breast disease. Environ Res. 2004;98:250-257.

47 Nickerson K. Environmental contaminants in breast milk. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2006;51:26-34.

48 Gray J., Evans N., Taylor B., et al. State of the evidence: the connection between breast cancer and the environment. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009;15(1):43-78.

49 Trock B.J., Hilakivi-Clarke L., Clarke R. Metaanalysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. JNCI. 2006;98:459-471.

50 Van Patten C.L., Olivotto I.A., Chambers G.K., et al. Effect of soy phytoestrogens on hot flashes in post-menopausal women with breast cancer: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1449-1455.

51 Messina M.J., Loprinzi C.L. Soy for breast cancer survivors: a critical review of the literature. J Nutr. 131(11 Suppl), 2001. 3095S-108S

52 Messina M.J., Wood C.E. Soy isoflavones, estrogen therapy, and breast cancer risk: analysis and commentary. Nutr J. 2008;7:17.

53 Verheus M., van Gils C.H., Kreijkamp-Kaspers S., et al. Soy protein containing isoflavones and mammographic density in a randomized controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(10):2632-2638.

54 Nishio K., Niwa Y., Toyoshima H., Tamakoshi K., et al. Consumption of soy foods and the risk of breast cancer: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(8):801-808.

55 MacGregor C.A., Canney P.A., Patterson G., et al. A randomised double-blind controlled trial of oral soy supplements versus placebo for treatment of menopausal symptoms in patients with early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:708-714.

56 Duffy C., Perez K., Partridge A. Implications of phytoestrogen intake for breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:260-277.

57 Quak S.H., Tan S.P. Use of soy-protein formulas and soyfood for feeding infants and children in Asia. AJCN. 68(6 Suppl), 1998. 1444S-1446S

58 Boyd N.F., Martin L.J., Noffel M., et al. A meta-analysis of studies of dietary fat and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:627-636.

59 Missmer S.A., Smith-Warner S.A., Spiegelman D., et al. Meat and dairy food consumption and breast cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:78-85.

60 Moorman P.G., Terry P.D. Consumption of dairy products and the risk of breast cancer: a review of the literature. AJCN. 2004;80:5-14.

61 Mignone L.I., Giovannucci E., Newcomb P.A., et al. Meat consumption, heterocyclic amines, NAT2, and the risk of breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(1):36-46.

62 Hanf V., Gonder U. Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123(2):139-149.

63 Boyd N.F., Stone J., Vogt K.N., et al. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1672-1685.

64 Missmer S.A., Smith-Warner S.A., Spiegelman D., et al. Meat and dairy food consumption and breast cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:78-85.

65 Cho E., Chen W.Y., Hunter D.J., et al. Red meat intake and risk of breast cancer among pre-menopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2253-2259.

66 Taylor E.F., Burley V.J., Greenwood D.C., Cade J.E. Meat consumption and risk of breast cancer in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1139-1146.

67 Egeberg R., Olsen A., Autrup H., et al. Meat consumption, N-acetyl transferase 1 and 2 polymorphism and risk of breast cancer in Danish post-menopausal women. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:39-47.

68 Michels K.B., Mohllajee A.P., Roset-Bahmanyar E., et al. Diet and breast cancer: a review of the prospective observational studies. Cancer. 2007;109(suppl):2712-2749.

69 Mukamal K.J., Rimm E.B. Alcohol consumption: risks and benefits. Curr Atherosc Rep. 2008;10:536-543.

70 Kune G.A., Vitetta L. Alcohol consumption and the etiology of colorectal cancer: a review of the scientific evidence from 1957 to 1991. Nutr Cancer. 1992;18(2):97-111.

71 Smith-Warner S.A., Spiegelman D., Yaun S.S., et al. Alcohol and breast cancer in women: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. JAMA. 1998;279:535-540.

72 Hamajima N., Hirose K., Tajima K., et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1234-1245.

73 Chen W.Y., Willett W.C., Rosner B., et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and breast cancer. (abstract). J Clin Oncol, 2005;23(suppl)., 7s. Abstract 515

74 Zhang S.M., Lee I.M., Manson J.E., et al. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in the Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:667-676.

75 Zhang S.M., Willett W.C., Selhub J., et al. Plasma folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and risk of breast cancer. JNCI. 2003;95:373-380.

76 Zhang S., Hunter D.J., Hankinson S.E., et al. A prospective study of folate intake and the risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 1999;281:1632-1637.

77 Deandrea S., Talamini R., Foschi R., et al. Alcohol and breast cancer risk defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2025-2028.

78 Knight J.A., Bernstein L., Largent J., et al. Alcohol intake and cigarette smoking and risk of a contralateral breast cancer: The Women’s Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(8):962-968.

79 Berrino F., Muti P. Mediterranean diet and cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1989;43(Suppl 2):49-55.

80 Carruba G., Granata O.M., Pala V., et al. A traditional Mediterranean diet decreases endogenous estrogens in healthy post-menopausal women. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56(2):253-259.

81 Tseng M., Sellers T.A., Vierkant R.A., et al. Mediterranean diet and breast density in the Minnesota Breast Cancer Family Study. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60(6):703-709.

82 Berrino F., Villarini A., De Petris M., et al. Adjuvant diet to improve hormonal and metabolic factors affecting breast cancer prognosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:110-118.

83 Wu A.H., Yu M.C., Tseng C.C., et al. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. AJCN. 2009;89(4):1145-1154.

84 Murtaugh M.A., Sweeney C., Giuliano A.R., et al. Diet patterns and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: the Four-Corners Breast Cancer Study. AJCN. 2008;87(4):978-984.

85 Hanf V., Gonder U. Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123(2):139-149.

86 Larsson S.C., Giovannucci E., Wolk A. Folate and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. JNCI. 2007;99:64-76.

87 Lewis S.J., Harbord R.M., Harris R., et al. Meta-analyses of observational and genetic association studies of folate intakes or levels and breast cancer risk. JNCI. 2006;98:1607-1622.

88 Velicer C.M., Ulrich C.M. Vitamin and mineral supplement use among US adults after cancer diagnosis: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):665-673.

89 de Souza Fêde A.B., Bensi C.G., et al. Multivitamins do not improve radiation therapy-related fatigue: results of a double-blind randomized cross-over trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30(4):432-436.

90 Neuhouser M.L., Wassertheil-Smoller S., Thomson C., et al. Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women’s Health Initiative cohorts. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):294-304.

91 de Ruijter W., Westendorp R.G., Assendelft W.J. Use of Framingham risk score and new biomarkers to predict cardiovascular mortality in older people: population based observational cohort study. BMJ. 338, 2009. a3083. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3083

92 Ali M.M., Vaidya V. Vitamin D and cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2007;3(4):225-230.

93 John E.M., Schwartz G.G., Dreon D.M., et al. Vitamin D and breast cancer risk: the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1975 to 1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:399-406.

94 Shin M.H., Holmes M.D., Hankinson S.E., et al. Intake of dairy products, calcium, and vitamin D and risk of breast cancer. JNCI. 2002;94:1301-1311.

95 Frazier A.L., Li L., Cho E., et al. Adolescent diet and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:73-82.

96 Frazier A.L., Ryan C.T., Rockett H., et al. Adolescent diet and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:R59-R64.

97 McCullough M.L., Rodriguez C., Diver W.R., et al. Dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and post-menopausalbreast cancer risk in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2898-2904.

98 Simard A., Vobecky J., Vobecky J.S. Vitamin D deficiency and cancer of the breast: an unprovocative ecological hypothesis. Can J Public Health. 1991;82:300-303.

99 Nunez C., Carbajal A., Belmonte S., Moreiras O., Varela G. A case-control study of the relationship between diet and breast cancer in a sample from 3 Spanish hospital populations. Effects of food, energy and nutrient intake. Rev Clin Esp. 1996;196:75-81.

100 Witte J.S., Ursin G., Siemiatycki J., et al. Diet and pre-menopausal bilateral breast cancer: a case-control study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;42:243-251.

101 Levi F., Pasche C., Lucchini F., et al. Dietary intake of selected micronutrients and breast-cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:260-263.

102 Knight J.A., Lesosky M., Barnett H., et al. Vitamin D and reduced risk of breast cancer: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:422-429.

103 Barton D.L., Loprinzi C.L., Quella S.K., et al. Prospective evaluation of vitamin E for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:495-500.

104 Zhang S., Hunter D.J., Forman M.R., et al. Dietary carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:547-556.

105 Tamimi R.M., Hankinson S.E., Campos H., et al. Plasma carotenoids, retinol, and tocopherols. and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:153-160.

106 Sato R., Helzlsouer K.J., Alberg A.J., et al. Prospective study of carotenoids, tocopherols, and retinoid concentrations and the risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(5):451-457.

107 Rock C.L., Natarajan L., Pu M., et al. Longitudinal biological exposure to carotenoids is associated with breast cancer-free survival in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(2):486-494.

108 Israël L., Hajji O., Grefft-Alami A., et al. (Vitamin A augmentation of the effects of chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancers after menopause. Randomized trial in 100 patients). 1985;136(7):551-554. Ann Med Interne (Paris)