chapter 51 Breast disease

BREAST HEALTH

Women of all ages should know the normal look and feel of their breasts—this is known as ‘breast awareness’. There is no evidence to support any specific technique for breast self-examination. For many women there is also a psychological barrier to conducting a technical systematic examination, often suggesting they are not confident in their technique. For these reasons women should be encouraged to get to know what is normal for them through normal activities such as showering, dressing, putting on body lotion, looking in the mirror. Most importantly, women should be encouraged to present early to their GP if they find a change in their breasts—they are not wasting their doctor’s time. This is important even if they have had a recent ‘normal’ mammogram.

Women who have a significant family history should be referred to a familial cancer or genetics clinic, where an individual surveillance program and management advice can be provided and, if appropriate, genetic testing can be conducted.1

BENIGN BREAST DISEASES

BREAST PAIN AND FOCAL BREAST NODULARITY

Breast pain

Management

Evening primrose oil (gamma-linolenic acid) has been shown to reduce pain, nodularity and tenderness, at a dose of 3 g daily.2 It has only minor side effects, including headache, nausea, gastrointestinal upset and possible drug interactions with anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents and phenothiazines. A trial of treatment should last 4 months and be monitored with a pain chart. It does not interact with oral contraceptives.

Several clinical studies in women have suggested that chasteberry (Vitex agnus castus) is efficacious in reducing symptoms associated with premenstrual symptoms (PMS) including mastalgia.2,3 This herb contains steroidal precursors and active moieties including progesterone, testosterone and androstenedione. Chasteberry may interact with oral contraceptives, other hormonal therapy and dopazmine antagonists such as haloperidol and prochlorperazine. Adverse effects reported include nausea, rash, headache and agitation.

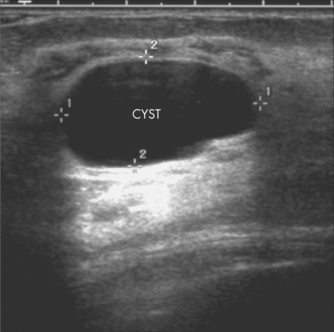

Benign breast lumps

Fibroadenomata

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, fibroadenomata may be managed by either surgical excision or regular clinical and imaging review over 12–18 months until the lesion is proved to be stable. Should the lesion significantly increase in size or develop atypical features on imaging, it should undergo excision biopsy. New palpable fibroadenomas in women aged over 40 years should be referred to a breast surgeon for consideration of excision biopsy, because the likelihood of a new lump being cancer increases with age.4

BREAST CANCER

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer diagnosed in women in developed countries and the greatest cause of cancer-related death in women.1,5 There is very good evidence that survival is related to the size and stage of the disease at diagnosis: the earlier the cancer is diagnosed, the greater the chance of effective treatment.1,5

AETIOLOGY

Despite much research into causes and risk factors for breast cancer, we have no means of preventing this disease.6 There are a number of factors that bear on the probability of a particular symptom being due to a breast cancer.

In general, breast cancer is a disease of ageing, with 75% of breast cancers diagnosed in women aged 50 years or older, and about 6% in women aged under 40 years. However, breast cancer can occur at any age and it is important that younger women who present with symptoms have these adequately investigated. Other factors that may increase risk for a particular woman include whether she has a significant family history of breast or ovarian cancer1 or a relevant inherited gene mutation, whether she has had a previous invasive or in situ breast cancer or a previous biopsy that shows atypical proliferative disease or other marker for increased risk.

Lifestyle factors

The World Health Organization estimates that 10% of breast cancer worldwide can be attributed to physical inactivity. It has also estimated that about 5% of breast cancers are attributable to alcohol consumption, and that overweight and obesity in postmenopausal women (BMI > 28) increases risk by about 30%.

The risk for breast cancer associated with taking the oral contraceptive pill is small, as the underlying risk for breast cancer is small at the age at which women are generally taking the Pill. The risk associated with HRT increases with increased duration of use, irrespective of the preparation or mode of administration. The decision about starting or staying on HRT must be made by the woman after being fully informed and weighing up the risks and benefits in her individual case.7,8

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

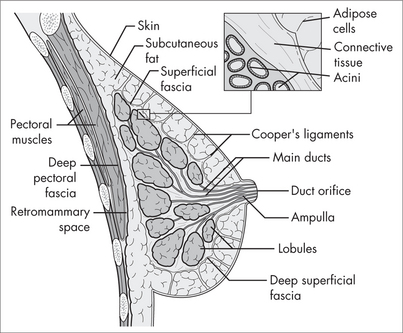

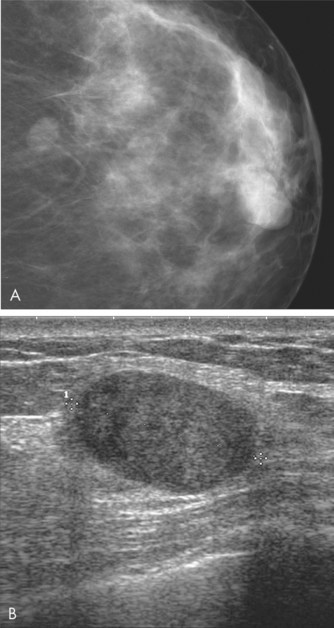

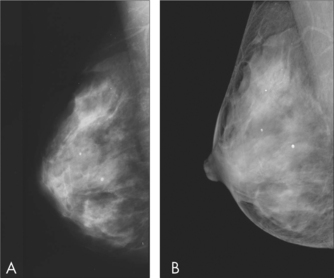

Breast imaging

Patient age is a factor in determining the most appropriate imaging modality. The sensitivity of mammography increases with increasing age. Mammography is recommended as the first imaging modality in women Aged over 50 years and should only be used in women under 25 years if the clinical or ultrasound findings are suspicious for malignancy. Ultrasound is more sensitive in detecting cancer in younger women, and is recommended as the first imaging modality in women aged under 35 years. In practice, both mammography and ultrasound are often used to provide complementary information in the evaluation of symptoms.

TREATMENT

The way in which a clinician relates to and communicates with a cancer patient can affect her wellbeing.9 Communication skills training is available to assist health professionals to manage difficult conversations such as breaking bad news and discussing prognosis.10

When organising referral for patients with breast cancer, GPs should consider both the preferences of the patient and the fact that patient outcomes are better if treated by clinicians who are part of a multidisciplinary team.11

Integrative management

Many patients raise the question of antioxidant use during chemotherapy. Despite the concerns of some oncologists, no trials have reported evidence of significant decreases in efficacy from antioxidant supplementation during chemotherapy.12

Supplements

Supplements may be recommended as adjunctive therapy for nutritional and immune system support, and for reducing the side effects and toxicity of cancer treatment (see ch 24, Cancer).

Psychosocial care

Psychosocial care should be considered alongside medical care for all patients with cancer, whose information and supportive care needs may change over time and should be monitored. It has been estimated that, at 3 months after diagnosis, 10–17% of women meet the criteria for major depression. Patients should be monitored for risk or symptoms of anxiety or depression, and referred to a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist for assessment. Psychological therapies have been shown to improve emotional adjustment and social functioning, reduce stress, and improve quality of life for patients with cancer.11

Cognitive behavioural techniques such as relaxation therapy, guided imagery, systematic desensitisation and problem solving have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing anxiety. Prayer and laughter are also effective for some individuals.11 Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting may benefit from psychological interventions, including cognitive behavioural techniques, relaxation and meditation.11

Traditional Chinese medicine

Chinese medicinal herbs, when used together with chemotherapy, may improve bone marrow function and quality of life.23 Other complementary botanicals are commonly used by cancer patients, although most have not been tested in rigorous clinical trials.

1 National Breast Cancer Centre. Advice about familial aspects of breast cancer and epithelial ovarian cancer: a guide for health professionals. Sydney: NBCC, 2006.

2 Newall C. Herbal medicines: a guide for health care professionals. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 1997.

3 Schellenberg R. Treatment for premenstrual syndrome with agnus fruit extract: prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322:134-137.

4 Houssami N, Cheung MN, Dixon JM. Fibroadenoma of the breast. Med J Aust. 2001;174:185-188.

5 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & National Breast Cancer Centre. Breast cancer in Australia: an overview 2006. Cancer Series No. 34. Cat. no. CAN 29. Canberra: AIHW, 2006.

6 National Breast Cancer Centre. Risk factors report. Sydney: NBCC, 2007.

7 National Health and Medical Research Council. Making decisions: should I use hormone replacement therapy? Canberra: NHMRC, 2005.

8 National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and risk of breast cancer. NBOCC Position Statement.

9 National Breast Cancer Centre. A guide for women with early breast cancer. Sydney: NBCC, 2003.

10 National Breast Cancer Centre. Communication Skills Training Initiative;. Online. Available: http://www.nbcc.org.au/bestpractice/commskills/, 2007. 10 October 2007.

11 National Breast Cancer Centre and National Cancer Control Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Sydney: NBCC/NCCI, 2003.

12 Block KI, Koch AC, Mead MN, et al. Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic efficacy: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(5):407-418.

13 Berstad P, Ma H, Bernstein L, et al. Alcohol intake and breast cancer risk among young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(1):113-120.

14 Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol. 2010; Apr 22. [Epub ahead of print].

15 Chajès V, Thiébaut AC, Rotival M. Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1312-1320.

16 Blask DE. Melatonin, sleep disturbance and cancer risk. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(4):257-264.

17 Lambe M, Wigertz A, Holmqvist M. Reductions in use of hormone replacement therapy: effects on Swedish breast cancer incidence trends only seen after several years. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121(3):679-683.

18 Katalinic A, Rawal R. Decline in breast cancer incidence after decrease in utilisation of hormone replacement therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(3):427-430.

19 Harvard School of Public Health. The nutrition source. Vitamins: the bottom line. HSPH; 2010. Online. Available: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/vitamins/index.html.

20 Nogues X, Servitja S, Peña MJ. Vitamin D deficiency and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women receiving aromatase inhibitors for early breast cancer. Maturitas. 2010; 14 Apr. [Epub ahead of print].

21 Hines SL, Jorn HK, Thompson KM, et al. Breast cancer survivors and vitamin D: a review. Nutrition. 2010;26(3):255-262.

22 Stevens RG. Circadian disruption and breast cancer: from melatonin to clock genes. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):254-258.

23 Zhang M, Liu X, Li J, et al. Chinese medicinal herbs to treat the side effects of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD004921.

24 Ezzo J, Richardson M, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD002285.

25 Carati CJ, Anderson SN, Gannon BJ, et al. Treatment of postmastectomy lymphoedema with low-level laser therapy: a double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1114-1122.