Breast Disease

Development, Anatomy, and Physiology

The first step in development of the embryonic breast is the appearance of a pair of longitudinal streaks, which are ectodermal thickenings on the ventral surface of the embryonic torso called the primitive mammary ridges, and commonly known as the ‘milk lines’.1 Paired lens-shaped placodes appear as thickenings at specific locations along these milk lines. These placodes may be numerous in other mammals, but generally develop as a single pair in humans. Epithelial cells invaginate from the placode into the underlying mesenchyme to form the breast bud. A dense mesenchymal stroma then coalesces around the bud. At the final stage of embryogenesis, proliferating epithelial cells sprout from the mesenchyme into a fat pad that has developed beneath the dermis.

There is a rudimentary ductal tree with lactiferous ducts established by 16 weeks. These ducts eventually coalesce at the developing nipple. The areola is seen first at 20 to 24 weeks, and a true nipple has developed by the final trimester. During the final weeks of gestation, placental estrogens stimulate the breast buds in both genders to enlarge and create a true breast nodule, about 1 cm in size, at birth. The ‘minipuberty of early infancy’, a bimodal surge in hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis activity that occurs after birth, may lead to persistent breast enlargement well into the first few months of life.2 The fall of hormonal levels to baseline at around 6 months of age may stimulate prolactin secretion and the production of small amounts of milk (‘witch’s milk’). Throughout prepuberty, breast tissue is minimal and the nipple lies nearly flush with the skin in both boys and girls.

The onset of puberty is characterized by an increase in pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and gonadotropins that stimulate estrogen production by maturing ovarian follicles.3 The onset of development of a mature breast, known as thelarche, results from estrogen-stimulated ductal development and site-specific adipose deposition. In the absence of significant levels of circulating estrogen, male adolescents fail to produce a significant breast mass. This is not the case in females where the normal stages of the female breast development have been defined by Marshall and Tanner (Table 75-1).4

TABLE 75-1

Normal Stages of Breast Development in Females

| Stage | Description |

| Stage 1 | Preadolescent: elevation of papilla only |

| Stage 2 | Breast bud stage: elevation of breast and areola as a small mound, enlargement of areola diameter |

| Stage 3 | Further enlargement of breast and areola, with no separation of their contours |

| Stage 4 | Projection of areola and papilla to form a secondary mound above the level of the breast |

| Stage 5 | Mature stage: Projection of papilla only, resulting from recession of the areola to the general contour of the breast |

Data from Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291–303.

Pathophysiology

Benign female breast disease in children can be seen as an aberration of normal development and involution (ANDI).5 ANDI links adult breast pathology to events in early breast development. Thus, many of the same disease processes observed in adults may be present in children. Fibroadenoma is a disorder of normal lobular development. Excessive stroma development results in juvenile hypertrophy. Benign conditions that result from ductal involution seen in older adults may be encountered during infancy, such as periductal mastitis, nipple discharge, and nipple retraction.

Breast cancer is extremely rare in children. When it is encountered, it is almost exclusively seen in late adolescence.6 The study of early mammary development has importance because signals that control mammary gland embryogenesis and involution may be deregulated in breast cancer.7

Disorders of Development and Growth

Neonatal Hypertrophy

The newborn breast bud may enlarge in response to newborn prolactin that rises from falling levels of maternal estrogen in the days after birth (Fig. 75-1).8 These involute spontaneously within a few weeks without specific treatment.

Polythelia

Extra nipples, areolae, and occasionally, a true accessory breast, may develop anywhere along the milk line from axilla to pubis in about 5% of children. They are most commonly located on the chest wall below the actual breast (Fig. 75-2).9 Unsightly polythelia should be excised.

Hypoplasia and Aplasia

Breast aplasia and hypoplasia may complicate Poland syndrome. Reconstruction of the chest wall and insertion of a breast prosthesis or breast reconstruction by a variety of flap techniques is usually indicated.10

Breast hypoplasia with an associated abnormality of pubertal development mandates an endocrinologic evaluation for ovarian failure, including gonadal dysgenesis, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and varieties of disorders of sexual development.3 Breast augmentation is an option for these patients.

Incisions during a central venous catheter or chest tube insertion, as well as drainage of a breast abscess, may interfere with later breast growth and development.11 Extreme care must be taken when placing these incisions, particularly in prematurely born infants in whom the breast bud may be barely visible.

Atrophy

Atrophy of the breast may result from weight loss from any cause. Hypothalamic suppression and hypoestrogenism may complicate eating disorders, further retarding breast growth.12 In an otherwise well-nourished adolescent, breast atrophy should prompt a search for endocrine disorders that result in low estrogen or increased androgen.

Premature Thelarche

The differential diagnosis of breast enlargement in females is listed in Box 75-1. Breast development is defined as premature if it occurs before 6 years of age.13 Premature thelarche is defined as isolated breast development without findings of puberty, such as pubic hair, vaginal mucosal estrogenization, linear growth spurt, adult body odor, and pubertal behavioral changes. It is unilateral in 50% of cases, has a peak incidence between 6 months to 2 years, and resolves spontaneously in more than half of patients.

Premature thelarche can be distinguished from physiologic perinatal breast development and precocious puberty.3 Precocious puberty is associated with two or more of the other features of puberty previously listed, and has a peak incidence between 5 and 8 years later than true premature thelarche. Gentle retraction of the labia allows inspection of the vaginal mucosa, which is reddish and delicate during its prepubertal state, and pink and thicker when estrogenized. About 20% of girls with premature thelarche proceed to develop precocious puberty.

Drugs, toxins. and environmental causes of premature thelarche should be considered.14 A number of compounds have been implicated in the disorder, including xenoestrogens (compounds that bind to the estrogen receptor), phytoestrogens (compounds in plants), environmental toxins (pesticides, cosmetics, and packaging material), and estrogens in poultry, cosmetics, and hair products.

Hypertrophy

Virginal breast hypertrophy arises from exaggerated responses to pubertal hormonal fluxes. Both stroma and ducts are hypertrophic. Breast tissue and skin becomes ischemic and necrotic from the weight. Little experience is available with nonoperative treatment, although some improvement has been reported with tamoxifen.15 Reduction mammoplasty is an appropriate procedure for virginal hypertrophy.9 Continued breast growth may require repeated reductions.

Unilateral hypertrophy may produce breast asymmetry. Decisions regarding operation to correct the asymmetry require judgment as asymmetry is often seen between the two breasts. Ongoing breast growth may magnify the asymmetrical differences. Once Tanner stage 5 breast maturity is reached, equalization in the size of the breasts is reasonable with augmentation and reduction techniques.

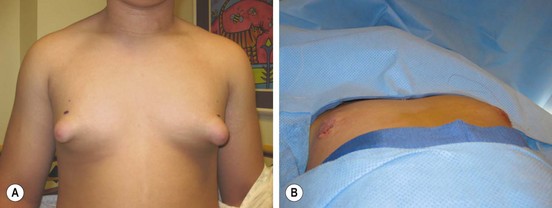

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia is the benign proliferation of glandular tissue of the male breast to the extent that it can be felt or seen as an enlarged breast (Fig. 75-3).16 Male breast enlargement can occur physiologically in the neonate, adolescent, or elderly. Gynecomastia that occurs before puberty warrants an urgent referral to a pediatric endocrinologist. Up to 60% of boys exhibit physiologic or pubertal gynecomastia. Although its etiology is not fully known, one hypothesis is that the effects of testosterone lag behind the estrogen effects at the onset of puberty. However, careful assays have not detected significant hormonal differences in boys with and without gynecomastia. Pubertal gynecomastia first appears between 10 and 12 years of age, with the highest prevalence at 13 to 14 years, corresponding to Tanner stage 3 or 4 (see Table 75-1). Involution is generally complete at 16 to 17 years, but may persist longer in obese boys.

FIGURE 75-3 (A) This teenager has gynecomastia, which was causing him discomfort as well as having negative psychosocial ramifications. (B) On the operating table, the enlarged breast tissue was removed and a nice cosmetic appearance achieved.

Pathologic gynecomastia results from conditions that cause imbalanced estrogen and androgen concentrations. Elevated estrogen levels occur in neoplasms that secrete the hormone or its precursors (e.g., testicular germ cell, Sertoli cell, and Leydig cell tumors) as well as adrenal neoplasms. Feminizing adrenal tumors are generally malignant. Increased aromatase conversion of androgens into active estrogen occurs in obesity and in infants with hepatocellular carcinoma. Decreased androgen levels or androgenic effects can result from gonadal failure that may be primary (e.g., Klinefelter syndrome, mumps orchitis, castration) or secondary (hypothalamic and pituitary disease). Serum levels of sex-hormone binding globulin affect the balance of free testosterone and estrogen. Displacement of androgens from their receptors by the many drugs associated with gynecomastia (Table 75-2) may result in unopposed estrogen effects in sex hormone-sensitive tissue, including the breast.

TABLE 75-2

Drugs Associated with Gynecomastia

| Drug | Examples |

| Hormones | Androgens, anabolic steroids, estrogens, estrogen agonists and human chorionic gonadotropic |

| Antiandrogens/inhibitors of androgen synthesis | Bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide, cyproterone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (leuprolide and goserelin) |

| Antibiotics | Metronidazole, ketoconazole, β-minocycline, isoniazid |

| Anti-ulcer | Cimetidine, ranitidine, omeprazole |

| Abuse | Alcohol, heroin, amphetamines |

| Chemotherapy | Methotrexate, alkylating agents, Vinca alkaloids, cyclophosphamide |

| Cardiovascular | Digoxin, furosemide, spironolactone, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (captopril and enalapril), calcium channel blockers (diltiazem, nifedipine, verapamil), reserpine, amiodarone, α-methyldopa, sprionolactone, and minoxidil |

| Psychiatric/neurologic | Anxiolytic agents (e.g., diazepam), tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, haloperidol, phenytoin, risperidone, clonidine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Other | Antiretroviral therapy for HIV, metoclopramide, penicillamine, phenytoin, sulindac, cyclosporine |

From Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: Pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:1010–15. Reprinted with permission.

Indications for operation include severe pain, tenderness, or embarrassment sufficient to interfere with the patient’s activities. Subcutaneous mastectomy through a periareolar incision and liposuction are both acceptable.9,17 It has been suggested that histologic examination of excised breast tissue from adolescent boys may be unnecessary because breast cancer has never been found in male children with gynecomastia.18 However, a report of bilateral ductal carcinoma in gynecomastia specimens in three adolescent boys is concerning.19 Assessment of the effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions in this population are problematic because so many cases resolve without therapy.

Inflammatory Lesions

Breast Trauma and Fat Necrosis

Fat necrosis, a benign condition that can mimic breast carcinoma, may develop in injured areas of the breast.20 An area of fat necrosis may create a mass with features that suggest carcinoma: painless, firm, fixed, tethered and thickened skin, and spiculated calcifications on mammography. The rarity of malignancy in adolescent girls is reassuring, but biopsy may be necessary to exclude malignancy.

Mastitis and Abscess

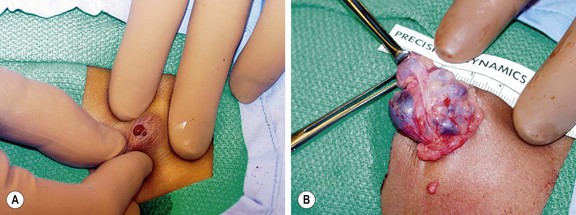

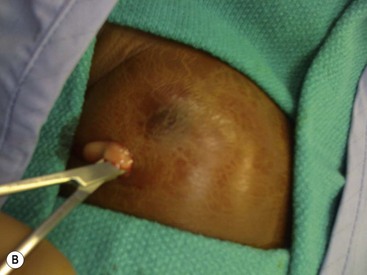

Infections in the neonatal breast affect the breast before the ductal involution occurs later in infancy.21 The peak incidence of neonatal infections is in the fourth and fifth weeks of life and affects girls more often than boys (3.5 to 1). Staphylococcus is the causative organism in more than 90% of cases. Streptococcus, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli have also been found. The skin and nipple are red with swelling and edema surrounding the area with simple mastitis (Fig. 75-4A). Fluctuance and deep discoloration suggest an abscess or extension of infection beneath the fascia. A small drop of pus may be expressed from the nipple due to insufficient drainage if an abscess is present. Fever, irritability, and refusal to feed may be present in 10–25% of patients. A quarter have pustular skin lesions elsewhere, usually in the inguinal region. Ultrasound (US) may be useful in diagnosis, distinguishing abscesses from inflammation.22

FIGURE 75-4 (A) A breast abscess is seen in a one month-old girl with redness and induration surrounding the breast bud. (B) Incision and drainage was performed through a limited incision at the inferior aspect of the abscess to avoid injuring the breast tissue under the nipple.

Mastitis in neonates generally responds to antibiotics and warm packs to the affected breast. Initial antibiotic therapy should cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Progression of inflammation while taking antibiotics suggests the presence of an abscess that requires incisional drainage (I & D), or an organism other than MRSA. When draining an abscess, it is important to avoid damage to the breast bud and its vascular supply as breast deformity later in adolescence may result. Needle aspiration is the recommended initial intervention, with repeated aspirations performed if the inflammatory signs improve. A true abscess may require I & D in an area away from the developing breast bud (Fig. 75-4B). One study documented a significant decrease in breast size relative to the opposite breast in two of five patients who required I & D of a breast abscess as a neonate.23

Nipple Discharge

Galactorrhea

Galactorrhea is lactation not related to pregnancy.24 The five etiologic groups are neurogenic, hypothalamic, endocrine, drug-induced, and idiopathic. Neurogenic causes result from local breast and nipple irritation and stimulation. Prolactinoma, the most common hypothalamic cause of galactorrhea in adults, is rare in childhood and adolescence.25 Cessation of oral contraceptives, polycystic ovary, adrenal tumors, and gonadal tumors may cause galactorrhea in adolescents. Galactorrhea in boys is always abnormal and a prolactinoma is the most common cause.

Other Nipple Discharges

Nonmilky discharges include pus, cyst contents, and blood.26 Serous drainage of brown to green fluid may indicate the presence of a communicating breast cyst, and is usually self-limited. Bloody drainage, a sign of cancer in adults, usually occurs from an intraductal papilloma or ductal ectasia in children and adolescents. Bloody nipple drainage should be cultured because it may be positive for Staphylococcus which should be treated if positive. Most causes of nipple discharge are self-limited and resolve spontaneously. Excision of the abnormal duct is indicated if drainage persists or recurs (Fig. 75-5).

Mastalgia

Although common in adults, breast pain (mastalgia) is poorly characterized and often underreported among young and adolescent girls.27 Initial evaluation should focus on exclusion of masses and inflammatory causes. Pain is characterized as cyclic or noncyclic, which is an important distinction as cyclic pain is more likely to respond to therapy. Up to 22% of cyclic and 50% of noncyclic cases resolve without therapy in one year. Dietary interventions help, such as restriction of caffeine and other methylxanthines, and additional flaxseed products. Vitamin E and evening primrose oil have not shown clinical benefit. Tamoxifen, danazol, and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory gels may improve symptoms.27

Breast Masses

Evaluation of Breast Masses

The age of the patient affects the differential diagnosis and the diagnostic approach for breast masses in children (Boxes 75-2 and 75-3). Patient age with a complete history and physical examination are sufficient to make the diagnosis in most cases. In a review of 374 breast specimens from patients aged 20 years and younger, the majority were identified as benign and fell into these three categories: fibroadenoma (44%), gynecomastia (22%), and juvenile hypertrophy (14%).28 Twenty-two lesions were a variety of soft tissue tumors, including phyllodes tumor, granular cell tumor, neurofibroma, angiosarcoma, stromal sarcoma, metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, giant cell fibroblastoma, and only one papillary carcinoma.

Traditional terms, such as fibrocystic disease, lack pathological and clinical precision. An accurate diagnosis based on histology defines the risk for malignancy so that appropriate interventions may be initiated.29 Thus, evaluation of breast masses require imaging and tissue sampling.

Regarding diagnostic evaluation, multiple radiographic and interventional options are available. Ultrasound distinguishes cystic from solid masses. Diagnostic mammography and magnetic resonance imaging are not routinely used in adolescents. Fine needle aspiration (25 or 22 gauge) will empty simple cysts and sample sufficient numbers of cells to make the diagnosis of fibroadenoma and ductal hyperplasia.30 Core needle biopsy (14 to 9 gauge) with vacuum or automated devices provides larger samples with architectural detail. Sonography locates deep and small lesions for needle biopsy if a mass is difficult to palpate. Unfortunately, small adolescent breasts may not accommodate a core biopsy needle, and open biopsy is occasionally necessary.

Recent clinical evidence indicates that breast self-examination does not affect breast cancer outcome, with one national task force recommending against it.31 Individuals with an inherited predisposition to breast cancer should begin intensive monitoring between ages 20 and 25 years.32

Benign Breast Disease

Pearlman classifies benign breast disease into three broad categories: nonproliferative disorders, proliferative disorders without atypia, and atypical hyperplasia.29 Simple cysts, hyperplasia, and duct ectasia comprise the nonproliferatrive group. Fibroadenomas, papillomas, tubular adenomas, benign phyllodes tumors, and mild epithelial hyperplasia represent proliferative disorders without atypia. Atypical hyperplasias include moderate or florid hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in-situ. The number of epithelial layers and degree that they fill the duct determine the difference between mild (four or fewer, do not fill the duct) and moderate or florid hyperplasia (more than four that often fill the duct). The three groups roughly parallel the relative risk for later development of breast cancer.33 Nonproliferative disorders generally do not increase breast cancer risk while proliferative disorders without atypia have a small increase (relative risk, 1.5–2.0). Lesions with atypical hyperplasia pose a moderate risk of later development of cancer (>2.0). Benign breast disease encountered in adolescence is nearly always in the lower risk categories.

Juvenile papillomatosis is a rare variant of epithelial hyperplasia, with a histological appearance that would be considered premalignant in adults.34 Histology includes ductal stasis and apocrine cysts that give it a descriptive pathological term, ‘Swiss cheese disease’. Some patients develop breast cancer later in adulthood, and one-fourth have a family history of breast cancer.

Tubular adenomas have prominent adenosis-like epithelial proliferation with sparse intervening stroma.35 They are generally seen in young women of childbearing age, and are rarely encountered in adolescents. Because they present as a well-circumscribed breast lump clinically indistinguishable from a fibroadenoma, these lesions require needle or excisional biopsy for tissue diagnosis.

Simple Cysts

Benign cysts can occur throughout childhood, however, they are commonly associated with thelarche.36 They are soft and painless, range in size from 1–10 mm in diameter, and are not fixed to surrounding breast tissue. They are thought to arise when acini or terminal ductules dilate and untwist. Those close to the skin may appear blue-tinged. The columnar epithelium that lines simple cysts have apocrine-like features, and may form papillary tufts. The apocrine changes may represent metaplasia, but these cysts do not have an increased cancer risk if they are not associated with other proliferative lesions that have a higher risk. Needle aspiration will usually show serous or brown fluid, and results in complete resolution. Biopsy is required if the mass persists after aspiration.

Fibroepithelial Tumors

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas are the most common breast mass seen by pediatric surgeons.28 Two variants, adult and juvenile, affect children. Adult fibroadenomas affect older adolescents and young women (Fig. 75-6). They may be multiple in 10–15% of cases. The mass is usually 1–2 cm in diameter, painless, distinct, rubbery, and mobile. A fibroadenoma does not have a true capsule, but rather a well-demarcated stromal interface where the tumor comes in contact with normal tissue. Areas of focal hemorrhage may be present, and lead to pain and rapid enlargement. Juvenile fibroadenomas affect younger adolescents around the time of puberty.37 In contrast to an adult fibroadenoma, the juvenile variant tends to be much larger (average diameter 4 cm), and may cause considerable breast deformity. Microscopic examination reveals a rich cellular stroma and a prominent glandular epithelium.

FIGURE 75-6 This 16-year-old developed an enlarging, painful fibroadenoma in her left breast. The lesion measured 7 cm × 5 cm × 4 cm on ultrasound examination. She underwent excision of the medially placed lesion through a circumareolar incision and tolerated the operation well. The histologic examination returned a benign fibroadenoma. Her symptoms have resolved.

Fibroadenomas are benign, but the adult variant is a long-term risk factor for breast cancer and can harbor a carcinoma.34,38 Ductal carcinomas have not been reported in juvenile fibroadenomas; however, juvenile variants may be related to phyllodes tumors.

Fine-needle aspiration is useful in distinguishing fibroadenomas from carcinomas and phyllodes tumors. Differentiating fibroadenomas from other benign conditions is more difficult.39 Fibroadenomas can be followed without operation if the lesion is less than 3 cm in diameter and exhibits the expected characteristic features: solitary, firm, rubbery, nontender, and well circumscribed.40 The probability of disappearance of the mass is 0.46 at 5 years and 0.69 at 9 years.41 Because of the rarity of breast cancer among adolescents, it is reasonable to wait a period of years to see whether a small lesion will disappear.

Fibroadenomas that are growing should be excised to avoid further enlargement and preserve the architecture of the remaining normal breast tissue. A periareolar incision gives a better cosmetic result at 6 months, but results in an increased incidence in loss of nipple sensation.42 Recently, a minimally invasive approach to facilitate removal of a giant juvenile fibroadenoma has been described.43 Rapid growth may lead to impressively large lesions that require complex reconstructive surgery.9

Phyllodes Tumors

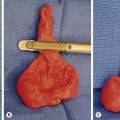

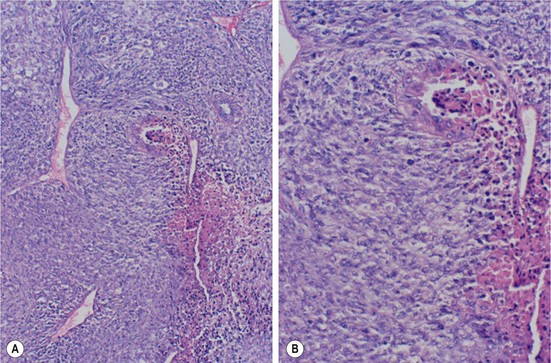

Phyllodes tumors, formerly called cystosarcoma phyllodes, are rare fibroepithelial tumors that can be benign (with significant risk for local recurrence) or malignant (with rapidly growing metastases).44 They can range in size from 1–40 cm. Only about 10% of phyllodes tumors occur in women younger than the age of 20 years. The clinical presentation is a rapidly growing breast mass larger than 6 cm. Like a fibroadenoma, a phyllodes tumor lacks a true capsule and appears well circumscribed. Features that distinguish it from a fibroadenoma are fibrous areas interspersed with soft fleshy areas, and cysts filled with clear or semisolid bloody fluid. There may be epithelial and stromal hyperplasia and areas of atypia, metaplasia, and malignancy. The mitotic activity in the stromal elements determines whether a phyllodes tumor is malignant (Fig. 75-7). Clonal activity from three patients in whom a phyllodes tumor of the breast developed after excision of a fibroadenoma suggests that the former developed from the latter.45

FIGURE 75-7 A 16-year-old girl underwent resection of a malignant phyllodes tumor. (A) Photomicrograph shows an area of necrosis typical of rapidly growing neoplasms (×10). (B) A higher-power view shows stromal and epithelial atypia and numerous mitotic figures (×20). (Courtesy of Edgar Pierce, MD, and Earl Mullis, MD, Medical Center of Central Georgia.)

The mean age of these patients is in the fourth decade, about a decade older than that for an adult fibroadenoma (mean age, 28.5 years in fibroadenoma, 44 years in phyllodes tumor). A phyllodes tumor tends to be larger (>4 cm in diameter) compared to a fibroadenoma. On sonography, cysts within an otherwise solid mass are indicative of phyllodes tumor. Diagnosis using fine-needle aspiration centers on the detection of a dimorphic pattern of stromal elements and benign epithelial tissue. The diagnosis of phyllodes tumor can be made from a core needle biopsy specimens in most cases.46 When the preoperative workup cannot distinguish between a fibroadenoma and a phyllodes tumor, excisional biopsy is indicated.

In cases in which the preoperative diagnosis is known, wide local excision with a 1 cm margin of normal breast tissue is recommended.47 Tumors that extend to the pectoralis fascia require removal of the muscle adjacent to the tumor. If the diagnosis of phyllodes tumor is discovered only after histologic examination, most authors recommend re-excision of normal breast tissue because of the 20% risk of local recurrence. Malignant phyllodes tumors are treated with simple mastectomy. Lymph node dissection is not indicated as these tumors do not metastasize to lymph nodes.

Breast Cancer

Malignancy of the breast in children falls into three groups: primary malignancies, metastatic tumors that involve the breast, and second malignancies. Although extremely rare in children, breast cancer has been found in both boys and girls under 5 years of age.48 More than 90% of children are first seen with a breast mass. Nipple discharge can also be a presenting sign. Thus, a cytologic examination of the fluid is advised.

Secretory carcinoma is the primary malignancy that occurs most often in children.49 Girls are affected five times more often than boys; however, the youngest patient reported is a 3-year-old boy.50 It may appear as a benign nodule or group of nodules on ultrasound.51 Clinically involved enlarged axillary lymph nodes are present in approximately 20% of cases. It has a low-grade clinical behavior with a good prognosis for long-term survival after simple mastectomy. Axillary node dissection is indicated if the nodes are clinically involved. Recurrence after lumpectomy has been described.49–51 Long-term follow-up is imperative owing to the indolent nature of the disease and the risk for late recurrence.

Nonsecretory breast cancers are less common in children. A 40-year review of adolescent patients at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center identified 10 patients with primary adenocarcinoma of the breast, four with malignant phyllodes tumors, and two with metastatic tumors.6 Ages ranged from 13 to 19 years. Four patients had a positive family history for breast disease. The cases of adenocarcinoma probably represent the leading edge of the prevalence distribution for adult primary breast cancer and included the histologic types seen in primary breast cancers in mature women: invasive intraductal, invasive lobular, and signet ring cancers. The treatment regimen is the same as for adult primary breast cancer and is dictated by histology, stage, presence of hormone receptors, tumor markers, and patient menstrual status.

The breast has also been reported as the primary site for leukemia, lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.28,52 More commonly, it is the site of acute leukemic relapse. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma appears to have a relative predilection for the breast, with 6% to 10% of cases metastasizing to the breast.53 Other childhood tumors (retinoblastoma, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma) may also metastasize to the breast.

References

1. McKiernan, J, Coyne, J, Cahalane, S. Histology of breast development in early life. Arch Dis Child. 1988; 63:136–139.

2. Kuiri-Hanninen, T, Kallio, S, Seuri, R, et al. Postnatal developmental changes in the pituitary-ovarian axis in preterm and term infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 96:3432–3439.

3. Loomba-Albrecht, LA, Styne, DM. The physiology of puberty and its disorders. Pediatr Ann. 2012; 41:el–9.

4. Marshall, WA, Tanner, JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969; 44:291–303.

5. Hughes, LE. Aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI): An update. In: Mansell RE, ed. Recent Developments in the Study of Benign Breast Disease. London: Parthenon; 1994:65–73.

6. Corpron, CA, Black, CT, Singletary, SE, et al. Breast cancer in adolescent females. J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 30:322–324.

7. Cowin, P, Wysolmerski, J. Molecular mechanisms guiding embryonic mammary gland development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010; 2:a003251.

8. Amer, A, Fischer, H. Images in clinical medicine. Neonatal breast enlargement. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1445.

9. van Aalst, JA, Phillips, JD, Sadove, AM. Pediatric chest wall and breast deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124:38e–49e.

10. Urschel, HC, Jr. Poland syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009; 21:89–94.

11. Eidlitz-Markus, T, Mukamel, M, Haimi-Cohen, Y, et al. Breast asymmetry during adolescence: Physiologic and non-physiologic causes. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010; 12:203–206.

12. Greydanus, DE, Matytsina, L, Gains, M. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. Prim Care. 2006; 33:455–502.

13. Lee, CT, Tung, YC, Tsai, WY. Premature thelarche in Taiwanese girls. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 23:879–884.

14. Rudel, RA, Fenton, SE, Ackerman, JM, et al. Environmental exposures and mammary gland development: State of the science, public health implications, and research recommendations. Environ Health Perspect. 2011; 119:1053–1061.

15. Hoppe, IC, Patel, PP, Singer-Granick, CJ, Granick, MS. Virginal mammary hypertrophy: Ameta-analysis and treatment algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:2224–2231.

16. Johnson, RE, Murad, MH. Gynecomastia: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009; 84:1010–1015.

17. Hodgson, EL, Fruhstorfer, RH, Malata, CM. Ultrasonic liposuction in the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 116:646–653.

18. Koshy, JC, Goldberg, JS, Wolfswinkel, EM, et al. Breast cancer incidence in adolescent males undergoing subcutaneous mastectomy for gynecomastia: Is pathologic examination justified? A retrospective and literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:1–7.

19. Lemoine, C, Mayer, SK, Beaunoyer, M, et al. Incidental finding of synchronous bilateral ductal carcinoma in situ associated with gynecomastia in a 15-year-old obese boy: Case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:e17–e20.

20. Taboada, JL, Stephens, TW, Krishnamurthy, S, et al. The many faces of fat necrosis in the breast. Am J Roentgenol. 2009; 192:815–825.

21. Stricker, T, Navratil, F, Sennhauser, FH. Mastitis in early infancy. Acta Paediatr. 2005; 94:166–169.

22. Borders, H, Mychaliska, G, Gebarski, KS. Sonographic features of neonatal mastitis and breast abscess. Pediatr Radiol. 2009; 39:955–958.

23. Rudoy, RC, Nelson, JD. Breast abscess during the neonatal period. Am J Dis Child. 1975; 129:1031–1034.

24. Hussain, AN, Policarpio, C, Vincent, MT. Evaluating nipple discharge. Obstet Gyncol Surv. 2006; 61:278–283.

25. Richmond, IL, Wilson, CB. Pituitary adenomas in childhood and adolescence. J Neurosurg. 1978; 49:163–168.

26. Marshall, PS, Duarte, GM, Torresan, RZ, Cabello, C. Bloody nipple discharge in childhood. Breast J. 2011; 17:692–693.

27. Rosolowich, V, Saettler, E, Szuck, B, et al. Mastalgia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006; 28:49–74.

28. Dehner, LP, Hill, DA, Deschryver, K. Pathology of the breast in children, adolescents and young adults. Semin Diag Pathol. 1999; 16:235–247.

29. Pearlman, MD, Griffin, JL. Benign breast disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:747–758.

30. Neal, L, Tortorelli, CL, Nassar, A. Clinician’s guide to imaging and pathologic findings in benign breast disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010; 85:274–279.

31. Gregory, KD, Sawaya, GF. Updated recommendations for breast cancer screening. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 22:498–505.

32. Clark, AS, Domchek, SM. Clinical management of hereditary breast cancer syndromes. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2011; 16:17–25.

33. Santen, RJ, Mansel, R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:275–285.

34. Gill, J, Greenall, M. Juvenile papillomatosis and breast cancer. J Surg Educ. 2007; 64:234–236.

35. Salemis, NS, Gemenetzis, G, Karagkiouzis, G, et al. Tubular adenoma of the breast: A rare presentation and review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2011; 4:64–67.

36. Grobmyer, SR, Copeland, EM, III., Simpson, JF, Page, DL. Benign, high-risk, and premalignant lesions of the breast. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM, III., eds. The Breast, Edition 4. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

37. Wechselberger, G, Schoeller, T, Piza-Katzer, H. Juvenile fibroadenoma of the breast. Surgery. 2002; 132:106–107.

38. Ozzello, L, Gump, FE. The management of patients with carcinomas in fibroadenomatous tumors of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985; 160:99–104.

39. Alle, KM, Moss, J, Venegas, RJ, et al. For debate: Conservative management of fibroadenoma of the breast. Br J Surg. 1996; 83:992–993.

40. Jayasinghe, Y, Simmons, PS. Fibroadenomas in adolescence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 21:402–406.

41. Cant, PJ, Madden, MV, Coleman, MG, et al. Nonoperative management of breast masses diagnosed as fibroadenoma. Br J Surg. 1995; 82:792–794.

42. Liu, X-F, Zhang, J-X, Zhou, Q, et al. A clinical study on the resection of breast fibroadenoma using two types of incision. Scan J Surg. 2011; 100:147–152.

43. Cheng, PJ, Vu, LT, Cass, DL, et al. Endoscopic specimen pouch technique for removal of giant fibroadenomas of the breast. J Pediatr Surg. 2012; 47:803–807.

44. Khosravi-Shahi, P. Management of non metastatic phyllodes tumors of the breast: Review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2011; 20:e143–e148.

45. Noguchi, S, Yokouchi, H, Aihara, T, et al. Progression of fibroadenoma to phyllodes tumor demonstrated by clonal analysis. Cancer. 1995; 76:1779–1785.

46. Johnson, NB, Collins, LC. Update on percutaneous needle biopsy of nonmalignant breast lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009; 16:183–195.

47. Chen, W-H, Cheng, S-P, Tzen, C-Y, et al. Surgical treatment of phyllodes tumors of the breast: Retrospective review of 172 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2005; 91:185–194.

48. Rogers, DA, Lobe, TE, Rao, RN, et al. Breast malignancy in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:48–51.

49. Li, D, Xiao, X, Yang, W, et al. Secretory breast carcinoma: A clinicopathological and immunophenotypic study of 15 cases with a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2012; 25:567–575.

50. Karl, SR, Ballantine, TV, Zaino, R. Juvenile secretory carcinoma of the breast. J Pediatr Surg. 1985; 20:368–371.

51. Mun, SH, Ko, EY, Han, BK, et al. Secretory carcinoma of the breast: Sonographic features. J Ultrasound Med. 2008; 27:947–954.

52. Pettinato, G, Manivel, JC, Kelly, DR, et al. Lesions of the breast in children exclusive of typical fibroadenoma and gynecomastia. A clinicopathologic study of 113 cases. Pathol Annu. 1989; 24(Pt2):296–328.

53. Hays, DM, Donaldson, SS, Shimada, II, et al. Primary and metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma in the breast: Neoplasms of adolescent females, a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997; 29:181–189.