Breast-conserving surgery

the balance between good cosmesis and local control

Introduction

One of these reviews (search date 1995) analysed data from six randomised controlled trials that compared breast conservation treatment with mastectomy.4 A meta-analysis of data from five of these six trials involving 3006 women found no significant difference in the risk of death at 10 years (odds ratio 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78–1.05). The sixth randomised trial used different protocols. In the second systematic review, nine randomised controlled trials involving 4981 women randomised to mastectomy or breast-conserving treatment were included in the analysis.5 A meta-analysis of these nine trials found no significant difference in the risk of death over 10 years: the relative risk reduction for breast-conserving surgery compared with mastectomy was 0.02 (95% CI − 0.05 to + 0.09).5 There was also no difference in the rates of local recurrence in the six randomised controlled trials involving 3006 women where data were available: the relative risk reduction for mastectomy versus breast-conserving surgery was 0.04 (95% CI − 0.04 to + 0.12).4

Selection of patients for breast conservation

Traditionally, single cancers clinically measuring 4 cm or less, without signs of local advancement, have been managed by breast-conserving treatment (Box 4.1). Different units have different size criteria and many units have a tumour size cut-off for breast-conserving surgery of 3 cm or less clinically.

Clinical tumour size overestimates actual tumour size. There is a much better correlation between pathological tumour size and the size measured on imaging, with ultrasound assessment being more accurate than mammographic measurements.8 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appears better than ultrasound in assessing disease extent, particularly in invasive lobular carcinoma.9 The problem with MRI is that it has a low specificity and a low positive predictive value in that only two-thirds of lesions identified by MRI as suspicious of malignancy are subsequently confirmed as malignant.10 The role of MRI in assessing patients for breast-conserving surgery has been investigated in a randomised study and the conclusions of this study were that routine use of MRI is not worthwhile.8,11 MRI did not reduce the rate of incomplete excisions and was not associated with a reduction in short-term local recurrence but did significantly increase the mastectomy rate in patients who were otherwise considered good candidates for breast-conserving surgery. It is the balance between tumour size as assessed by imaging and breast volume that determines whether a patient is suitable for breast-conserving surgery rather than tumour size per se. Options for patients with tumours considered too large, relative to the size of the breast, for breast-conserving treatment include neoadjuvant systemic therapy to shrink the tumour, an oncoplastic procedure (see Chapter 6) involving either transfer of tissue into the breast or remodelling of the breast with surgery to the opposite breast to obtain symmetry (see Chapter 6).12,13 In a patient with small breasts, excision of even a small tumour may produce an unacceptable cosmetic result.

Patients with multiple tumours in the same breast have not previously been considered good candidates for breast-conserving treatment because they were reported to have a high reported incidence of in-breast recurrence14,15 and so have usually been treated by mastectomy, combined in appropriate patients with immediate reconstruction. Recent evidence has, however, demonstrated similar rates of local recurrence for both patients with unifocal and with multifocal and even multicentric disease.16,17 If it is feasible to excise the separate cancers in different parts of the breast and produce an acceptable cosmetic outcome then such patients should no longer be treated routinely by mastectomy. Satisfactory rates of local control following breast-conserving treatment for multifocal or multicentric cancers are achieved providing all disease is excised to clear margins.16,17 Early studies on multifocal and multicentric cancers often failed to achieve clear margins and this explains the high rates of local recurrence reported in these early series.15 Patients with bilateral cancers can also be treated by bilateral breast conservation. The rates of breast-conserving surgery vary significantly between countries and within countries. These rates are clearly influenced as much by the views of the surgeon treating the patient as the availability of radiotherapy locally. Failure to offer breast-conserving surgery to suitable and appropriate patients has become a medico-legal issue. If a patient who fulfils the criteria for breast-conserving surgery is treated by mastectomy then the exact reasons for the decision to proceed to mastectomy should be recorded legibly in the patient’s notes. Some patients choose mastectomy in preference to breast-conserving surgery but do so based on an inadequate understanding that outcomes for the two treatments are identical. In one series of patients choosing mastectomy rather than breast-conserving surgery, over half of patients did not know that mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery produces identical rates of survival.18

Breast-conserving surgery

Two surgical procedures have been studied extensively: quadrantectomy and wide local excision. Quadrantectomy was based on the belief that the breast is organised into segments, with each segment draining into its own major duct, and that invasive cancer spreads down the duct system towards the nipple.19 Both of these premises are incorrect.

The effectiveness of quadrantectomy relates to the large amount of tissue excised around the tumour rather than to the removal of a cancer and its draining duct. In an early randomised study of lumpectomy or quadrantectomy, a significantly greater number of patients who had lumpectomy had incomplete local excisions.20 Not surprisingly, therefore, local recurrence was more common after lumpectomy than after quadrantectomy, although survival was no different.20 Other non-randomised studies have shown similar rates of local recurrence for both quadrantectomy and wide local excision, providing margins of excision are clear.21 Quadrantectomy or segmental excisions are no longer appropriate breast-conserving options because they produce identical rates of local recurrence to wide excision but produce a significantly poorer cosmetic outcome compared with wide excision.22

Special technical details: wide local excision

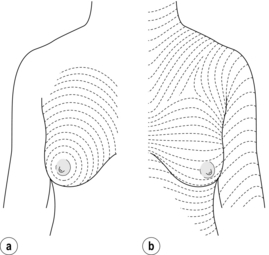

The aim of wide local excision is to remove all invasive and any ductal carcinoma in situ with a margin of normal surrounding breast tissue. Controversy has surrounded which incisions give the best cosmetic results. The predominant orientation of collagen fibres in the skin was described by Langer25 and these skin crease lines around the breast are essentially circular (Fig. 4.1). Subsequent work by Kraissl26 demonstrated that the lines of maximum resting skin tension run in a more transverse orientation across the breast (Fig. 4.1). In general, scars that are parallel both to the lines of maximum resting skin tension and to the orientation of collagen fibres are quickest to heal and produce the best cosmetic outcomes, with the lowest rates of scar hypertrophy and keloid formation.

Figure 4.1 The direction of Langer’s lines (a) and lines of maximum resting skin tension in the breast (b) (so-called dynamic lines of Kraissl).

Having made the skin incision, the skin and subcutaneous fat are dissected off the breast tissue. Care should be taken when elevating skin not to remove subcutaneous fat unnecessarily as thin skin flaps give a poor postoperative cosmetic result. Where the cancer is close to the skin, hydrodissection infiltrating 1 in 400 000 adrenaline in saline can help to separate the skin and subcutaneous fat from the breast tissue and breast fat, and facilitates skin elevation over the cancer. Skin flaps beyond the edge of the cancer for at least 1–2 cm are mobilised. This allows the fingers of the non-dominant hand to be placed over the palpable cancer. The breast tissue is then divided beyond the fingertips. The line of incision through the breast should be approximately 1 cm beyond the limit of the palpable mass. Having incised through the breast tissue, dissection continues under the cancer. In the majority of patients it is necessary to divide the whole thickness of breast tissue down to the pectoral fascia, to ensure that there is an adequate margin of tissue removed deep to the cancer. If the lesion is superficial, and there is a significant amount of breast tissue deep to the cancer, it may not be necessary to remove full thickness of breast tissue. Likewise if the lesion is deep, more tissue can be left superficially on the skin flaps. Having reached the deep margin, which is usually the pectoral fascia, the breast tissue and cancer are lifted from this fascia. It is not necessary to excise pectoral fascia unless it is tethered to the tumour or the tumour is involving it. If a carcinoma is infiltrating one of the chest wall muscles, then a portion of the affected muscle should be excised beneath the tumour, the aim being to remove sufficient muscle to get beyond the limits of the cancer. Having dissected under the cancer, the cancer and surrounding tissue are grasped between the finger and thumb of the non-dominant hand and excision of the cancer at the other margins is completed. The specimen should be orientated immediately following excision with Liga-clips, sutures or metal markers, prior to specimen radiography and submission to the pathologist.27 Metal markers or Liga-clips are preferred because they can be seen on specimen radiography. Routine X-ray of orientated specimens is recommended because it has been shown to help the surgeon confirm the target lesion has been excised and allows assessment of completeness of excision at the radial margins.27 If the specimen radiograph shows the cancer or any associated microcalcification is close to a particular margin, then further tissue can and should be removed from the margin of concern, before being orientated and sent to pathology.

A number of studies have evaluated the use of cavity shavings and bed biopsies, but few have compared these with standard assessment of margins. A minority of surgeons continue to take cavity shavings and bed biopsies routinely. Neither has been shown to be reliable indicators of local recurrence. A major concern of taking cavity shavings routinely is that significant amounts of extra breast tissue can be removed, particularly if the whole cavity is shaved; this unfortunately can adversely affect cosmetic outcome. Most importantly, however, centres who do not use these techniques report excellent local control rates, which have continued to fall over time.28,29 Wide excision with standard examination of margins thus provides sufficient information on margin status for clinical use. Bed biopsies or cavity shavings are only of value and warranted where there is concern at operation that one particular margin is involved.

Having excised the cancer from the breast, suturing the defect in the breast without mobilisation of the breast tissue usually results in distortion of the breast contour. Defects in the breast are best closed by mobilising surrounding breast tissue from the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue and in some patients mobilisation from the underlying chest wall is required. Large defects (> 10% breast volume) that are left open fill with seroma, which often absorbs later, following which scar tissue develops and contracts and can result in an ugly distorted breast. Following large-volume excisions, after mobilisation it is usually possible to close the defect in the breast tissue by a series of interrupted absorbable sutures. Given the success of lipofilling or lipomodelling for improving some patients with poor cosmetic outcomes following breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy, a number of surgeons are exploring whether immediate lipofilling after wide local excision can improve outcomes, particularly for women with small breasts. Very large defects require oncoplastic breast reshaping (see Chapter 6) or a latissimus dorsi miniflap.12,13 Drains are not necessary after wide local excision and should not be used routinely. They do not protect against haematoma formation and increase infection rates. Breast skin wounds should be closed in layers with absorbable sutures, finishing with a subcuticular suture.

Excising impalpable cancers

As for palpable lesions, all specimens should be orientated with Liga-clips or metal markers, or secured to an orientated grid so that an orientated specimen radiography can be performed. Radiography is best performed in an X-ray machine designed specifically to X-ray specimens, such as a Bioptics® machine. There have been conflicting reports about whether compressing the specimen affects the incidence of subsequent positive margins as reported by the pathologist. Orientated specimen radiography improves the rate of complete excision of impalpable cancers.27 Cooperation between surgeon and pathologist is required so that the area of concern can be identified and assessed by the pathologist to ensure adequacy of excision.

Factors affecting local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery

Until recently there was a reported large variation between different centres in recurrence rates following breast-conserving surgery combined with whole breast radiotherapy for invasive breast carcinoma. Over 80% of all local recurrences were reported to be located adjacent to the site of initial excision. This is no longer true and an increasing percentage of ‘recurrences’ in treated breasts are actually second primaries.25 Megavoltage radiation therapy delivered to the whole breast in a dose of 4000–5000 cGy given over 3–5 weeks continues to be used in most patients after breast-conserving surgery because radiotherapy both reduces the rate of local recurrence and improves overall survival.30 Studies continue to evaluate whether localised radiotherapy delivered either during or within a few days of surgery is as effective as whole-breast radiotherapy. As yet it has not been possible to identify groups of patients who do not require radiotherapy. However, there is likely to be a group of older patients with low-risk cancers (completely excised, node negative and hormone receptor positive on hormone treatment) and women of any age whose cancers have an extremely good prognosis (small grade 1 or special type cancers that are completely excised, node negative and hormone receptor positive on hormone treatment) whose rates of local recurrence without radiotherapy are acceptable. Following whole-breast radiotherapy, it is possible to increase the local dose of radiotherapy by boosting the tumour bed. This reduces local recurrence rates, particularly in younger women, although there are cosmetic penalties associated with the use of boost.31

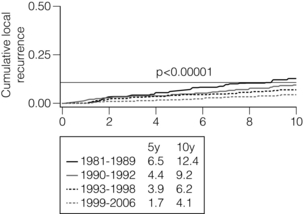

The rates of in-breast tumour recurrences continue to fall over time28,29 (Fig. 4.2). Whereas a 1 % annual rate of in-breast cancer events was formerly considered acceptable, rates are now less than 0.5 % per annum. The rates of in-breast tumour events continue at a similar rate for at least 20 years. This needs to be borne in mind when considering surveillance programmes for such patients.

Figure 4.2 Local recurrence rates in Edinburgh over four separate time periods showing a significant and continued fall in local recurrence rates over time. (Data unpublished, courtesy of Gill Kerr, Edinburgh Cancer Centre.)

Patient-related factors

In contrast, local recurrence is much less of a problem in older patients (> 65 years).

Recurrence is less frequent in women with large breasts but whether this relates to the larger excisions that can be performed in these patients or to alterations in steroid metabolism (fat is known to be an important site of conversion of androgens to oestrogens) is uncertain.36 A family history of breast cancer, particularly carriage of a mutation in one of the breast cancer genes, predisposes a patient to an increased rate of second primary cancers in both the treated and contralateral breast unless these women undergo a prophylactic oophorectomy, when local recurrence rates fall to levels similar to those of the general population.37,38

Tumour-related factors

Tumour location, tumour size, the presence of skin or nipple retraction, and the presence or absence of axillary node involvement have not been shown consistently to predict for local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery.39–42 The hormone receptor status of a breast cancer does not seem to exert any influence on local control rates.31–35,39–42 In-breast tumour recurrence has been reported to be more common in human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2)-positive cancers.

Tumour size

Size is not significantly associated with local recurrence. Only 3 of 28 series that have examined the relationship of tumour size and occurrence have shown any significant association between tumour size in breast recurrence.43,44 A large study from Boston44 demonstrated that cancers over 4 cm in size that were treated by breast conservation surgery had a rate of recurrence similar to that of smaller cancers (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Size of tumour related to local recurrence

| Size (cm) | Local recurrence (%) |

| 0–1 | 21 |

| 1.1–2 | 8 |

| 2.1–3 | 13 |

| 3.1–4 | 17 |

| 4.1–5 | 4 |

Data from Eberlein TG, Connolly JN, Schnitt JS et al. Predictors of local recurrence following conservative breast surgery and radiation therapy. The influence of tumour size. Arch Surg 1990; 125:771–9.

Tumour grade

A number of reports have analysed the relationship between tumour grade and local recurrence.

Although some series report a higher recurrence rate in grade 3 compared with grade 2 cancers, this is by no means universal.31–35,39–42 The relative risk of local recurrence between grade 1 and grade 2/3 cancer is approximately 1.5. The British Association of Surgical Oncology undertook a trial that randomised patients with node-negative grade 1 or special-type cancers to no further treatment, tamoxifen alone, radiotherapy alone or both radiotherapy and tamoxifen. A recent update of this study reported an exceedingly small rate of recurrence in patients randomised to radiotherapy and tamoxifen, and acceptably low rates of annual recurrence in patients treated with either tamoxifen alone or radiotherapy alone. Higher rates of recurrence were seen in patients who received neither radiotherapy nor tamoxifen. In these low-risk cancers treatment by radiotherapy alone or tamoxifen alone may therefore produce an acceptable rate of long-term control.

Histological type

There are few data relating histological tumour type to recurrence. Invasive lobular cancer has not been reported to be associated with a higher recurrence rate than so-called invasive ‘ductal’ carcinoma.45–48 One study did suggest that patients with invasive lobular carcinoma who developed local recurrence were more likely to develop multifocal recurrence42 but this has not been confirmed by others. Patients with invasive lobular cancer appear more likely than patients with no special-type tumours to have an incomplete excision. This is explained in part by the underestimation of tumour extent by mammography and ultrasound and the inability of surgeons to feel the extent of the cancer at operation. Patients with invasive lobular cancer on core biopsy should be warned of an increased likelihood of positive margins and where the extent of disease is not easy to assess on mammography and/or ultrasound, MRI may be valuable.9

Lymphatic/vascular invasion

Increased local failure rates have been reported in most, but not all, series in patients with histological evidence of lymphatic/vascular invasion (LVI).31–35,39–42,45–48 Of concern, the percentage of tumours reported to have LVI varies widely between different series by up to a factor of 4.

Extensive in situ component

The histological factor that was initially thought to be associated with an increased rate of local recurrence was the presence of an extensive in situ component (EIC) within and surrounding an invasive cancer. A tumour is defined as having EIC if 25% or more of the tumour mass is non-invasive and non-invasive carcinoma is also present in the breast tissue surrounding the invasive cancer.48 EIC was considered not only a predictor of local recurrence but also of residual disease within the breast following an incomplete wide excision. Early reports indicated that local recurrence rates were three to four times higher in cancers with EIC.31–35,39–42,45–48 The majority of these studies did not, however, take account of margins and the authors did not perform multivariate analysis. Providing clear margins are obtained, it is now known that there is no increased rate of local recurrence in patients with EIC.49–51 There is an interaction between age and EIC, with younger women being more likely to have EIC. It has been suggested that the higher frequency of EIC in younger women might explain some of the increased rate of local recurrence seen in younger women.42

Multiple tumours

Patients with macroscopically multiple cancers were formerly considered to have an increased risk of local recurrence compared with a patient with a unifocal cancer but patient numbers in such early series on which this evidence is based were small.14,15 If multifocality is identified by the pathologist or there are two cancers that are adjacent, then acceptable local recurrence rates can be obtained provided that all margins of excision are clear of disease. This led some to attempt breast-conserving surgery for patients with multiple separate tumours in the same breast. Provided that the cancers are excised completely and clear margins obtained then reports indicate a satisfactory rate of local control can be obtained with breast-conserving surgery in patients with both multifocal and multicentric cancers.16,17

Treatment-related factors

Controversy has surrounded how much extra tissue around a cancer needs to be removed and what constitutes an involved or positive margin. Some studies have defined a positive or involved margin as disease at the margin, others consider disease within 1 mm or even disease within 2 mm of the margins as involved. Conversely, negative margins or uninvolved margins have been variably defined as no tumour at the margin, or tumour within 1, 2, 5 and 10 mm of the margin. Whatever definition has been used, almost all studies have reported an increased rate of local recurrence in patients with positive, non-negative or involved margins. When comparing patients with involved margins to those with uninvolved or negative margins, the relative risk of local recurrence varies between 1.4- and 9-fold.28,29,31–35,39–42,45–47,49–54 This is despite, in almost half of these series, patients with involved or close margins having received higher doses of radiotherapy than patients with clear margins. In the few studies which found that margins are not important predictors of local recurrence, the dose of radiotherapy delivered to the tumour bed ranged from 65 to 72 cGy, i.e. a dose range that is effective without surgery.51–54 In one study, patients with involved margins who underwent re-excision to achieve a negative margin had a zero local recurrence rate; this compares with a 22% local recurrence rate in those patients who had re-excision but still had non-negative margins (P = 0.001).50 Surveys in the UK and USA have demonstrated that approximately 50% of surgeons aim for a margin of more than 2 mm, whereas 50% of surgeons are happy with a margin of 2 mm or less.55 There is thus no consensus about what constitutes an adequate margin of excision for breast-conserving surgery. A systematic review of margins and local recurrence was conducted by Singletary, who reported that some of the lowest rates of local recurrence were in centres that had used narrow margins of excision (1 or 2 mm).28 A recent large comprehensive meta-analysis of margins has confirmed that wider margins do not reduce local recurrence.29 Wider margins remove more tissue and so impact on cosmetic outcomes. The meta-analysis confirmed an increased rate of local recurrence for both involved and close (< 1 mm) margins.29 Compared with no ink on cancer cells a 1-mm margin was associated with a significantly lower rate of local recurrence. Recent data from Edinburgh show there is no need to re-excise if anterior or posterior margins are < 1 mm, providing full thickness of breast tissue has been excised and boost radiotherapy given. Unpublished data from Edinburgh show similar local recurrence rates whether the distance to the nearest margin was in the range 1–5 mm or 5–10 mm, confirming the results from the meta-analysis that narrow 1-mm margins are sufficient.

A recent large series of patients treated by breast-conserving surgery with a ≥ 1 mm margin reported rates of local recurrence of < 0.5% per year (Fig. 4.2).56 The majority of these so-called recurrences were in fact second primaries. In conclusion, a 1- or 2-mm margin is adequate and produces acceptable rates of long-term control. Any centre excising margins wider than 1 or 2 mm on breast-conserving excisions should consider their protocols.

Studies have looked at the presence of lobular carcinoma in situ57 and atypical ductal hyperplasia58 at the margins of excision. Neither of these features significantly increases local recurrence rates and so there is no need for re-excision if the pathologist reports these features alone at any of the margins of excision.

Age interacts with margins. Involved margins have their greatest impact on local recurrence in younger rather than in older women.53

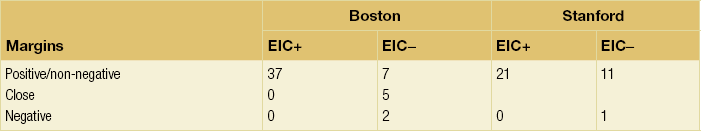

There is a direct interaction between EIC and margins (Table 4.2). Patients with EIC and positive margins who proceeded to radiotherapy without re-excision had a 37% local recurrence rate in a series from Boston48 and a 21% recurrence rate in a Stanford series.50 In contrast, patients with EIC and negative margins, on primary or re-excision, had a zero local recurrence rate. These two studies demonstrate that patients with EIC do not have an increased rate of local recurrence providing the margins of excision are clear of invasive and in situ cancer.

Table 4.2

Local recurrence rates (%) at 5 years in patients from Boston48 and Stanford50 subdivided by margin status and the presence (EIC +) or absence (EIC −) of an extensive in situ component

Patients undergoing re-excision for close or involved margins have only a 30% incidence of residual cancer in re-excised tissue.59 More than two foci of microscopic margin involvement in the original wide excision appears to be associated with a greater incidence of residual cancer (65%) compared with fewer than two foci, which had a much lower rate of residual cancer. If there was no residual disease at re-excision then there was a 4% local failure rate at 4.7 years compared with a 13% failure rate in patients who had residual disease at re-excision. Patients younger than age 50 in this study were also more likely to have disease in the re-excision specimen. The conclusion was that the majority of patients who undergo re-excision do not benefit from this procedure. Patients with lucent breasts and a well-defined lesion appear particularly unlikely to benefit from re-excision, if margins are close or focally positive, whereas younger women with dense breasts are much more likely to benefit from further surgery, as many of these women will have residual disease in the re-excision specimen.59 Further studies in this area are required. If it were possible to identify a group of women who do not benefit from re-excision, this would have great clinical utility.

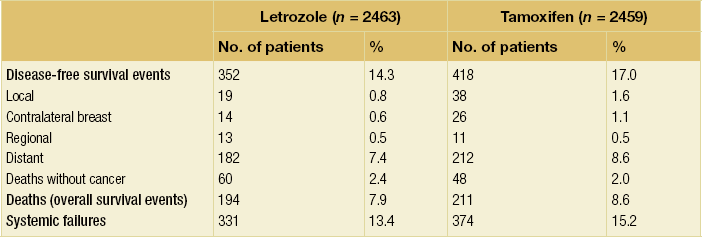

Adjuvant systemic therapy

Aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen and chemotherapy, in the presence of radiotherapy, reduce local recurrence rates after breast-conserving surgery.60,61 In the absence of radiotherapy, aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen or chemotherapy alone do not produce satisfactory rates of local control apart from in low-grade, node-negative cancers.62 The interval between surgery and radiotherapy may be important and there are suggestions that the rates of local recurrence increase if radiotherapy is delayed. The sequencing of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the subject of ongoing trials but it appears that giving both synchronously rather than sequentially improves local recurrence.

Factors influencing cosmetic outcome after breast-conserving surgery

There is a great variation in different series in the number of patients with good to excellent cosmetic results after breast-conserving surgery (Fig. 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Examples of excellent (a) and poor (b) cosmetic results from breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy.

Patient factors

There is conflicting evidence about whether age influences cosmetic outcome, with some studies claiming that older women have worse cosmetic results than younger women.1 One problem in younger women is that as the patient ages the normal contralateral breast tends to increase in size, whereas the treated breast tends not to and some treated breasts shrink. A treated breast that is symmetrical immediately following treatment can thus become asymmetrical over time.

There is a trend towards increased fibrosis in larger breasts, which leads to poorer cosmetic results than seen in smaller breasts.63 For this reason large-breasted women may be best treated by an operation that excises their cancer and at the same time reduces the volume of the breast (therapeutic mammaplasty). The best option to achieve symmetry in such women is to reduce both breasts through reduction-type incisions. Better cosmetic results following breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy are obtained in medium- and moderate-sized breasts; achieving a good cosmetic outcome can often be a problem in small breasts.1

Tumour factors

Increasing tumour size means that increasingly large amounts of tissue have to be removed. The volume of tissue excised is the most important factor relating to cosmetic outcome and so not surprisingly patients with larger tumours tend to have worse cosmetic results than women with smaller cancers.64,65 There are some data indicating that in surgery for small and impalpable cancers, a disproportionately large amount of normal surrounding breast tissue is removed to ensure that all the affected tissue is excised. The role of the surgeon is to excise the cancer completely in as small a volume as possible. Removing large volumes of tissue when excising small screen-detected cancers is not satisfactory surgical practice.

Location of tumour

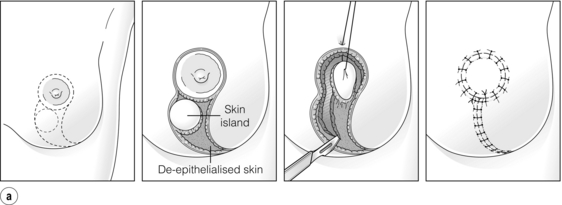

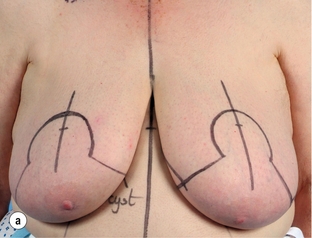

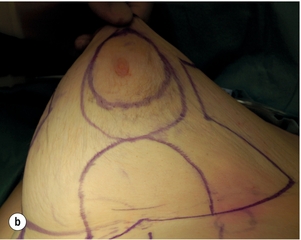

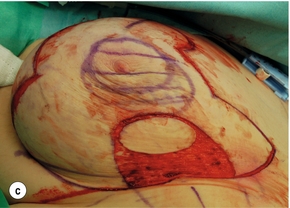

Cosmetic outcomes tend to be better if the tumour is located in the upper outer quadrant.66 Studies have shown that major downward displacement of the nipple occurs when surgery is performed on tumours located in the inferior half of the breast. This can be corrected at the time of initial surgery by de-epithelialising a crescentic portion of skin above the nipple to re-centre it on the new breast mound (see Chapter 6). If the tumour is central and the nipple–areola complex needs to be removed, then this can have a major effect on cosmetic outcomes.1 This is why central tumours were at one time considered a relative contraindication to breast-conserving surgery. However, studies have suggested that excision of central cancers not directly involving the nipple–areola complex can be treated by wide excision and nipple preservation, without significantly increasing the rate of local recurrence compared with more peripherally situated cancers.67 Good cosmetic outcomes are possible in some women with this approach (Fig. 4.4). In women with moderate-sized breasts who have cancers that directly involve, or are very close to the nipple, the nipple and/or areola can be excised in continuity with the cancer and the skin closed by a purse-string suture (Fig. 4.5). Another option is to rotate a dermoglandular local flap from the lower part of the breast to fill the defect (Fig. 4.6). This produces very satisfactory cosmetic outcomes.68 In women with central superficial cancers in larger breasts, the nipple can be excised as part of a reduction-type procedure with direct closure, or the defect caused by excising the nipple and areola can be filled with a new island of skin developed on an inferior dermoglandular pedicle. This can only be performed if there is at least 9 cm of skin between the margin of skin excision and the inframammary fold (Fig. 4.7).

Figure 4.4 Good cosmestic results from excision of a subareolar cancer left breast via a circumareolar incision.

Figure 4.5 Result after a central excision of a cancer and use of a purse-string suture to close the central defect.

Figure 4.6 (a) How to excise a central cancer under the nipple and produce a satisfactory cosmetic outcome without major breast distortion. This procedure has been called central quadrantectomy. The nipple–areola complex is excised and a portion of skin inferior is marked out. An incision around the circular skin island is made and the remaining skin around the island is de-epithelialised. A full-thickness incision is then made in the breast and the skin island is rotated to fill the central defect. Staples are useful to position the flap. When the flap is deemed to be in an optimal position, the staples are removed and the wound closed in two layers with absorbable sutures. (b) Final result from a right wide local excision Grissotti flap and nipple reconstruction.

Figure 4.7 (a) Patient prior to operation – cancer under right nipple evident by asymmetry with right nipple flatter and right nipple higher than left. (b) Preoperative markings showing the area around the nipple that will be excised. (c) Operative view of the island of skin that is mobilised on a de-epithelialised inferior dermoglandular flap. (d) Final result after radiotherapy prior to nipple reconstruction.

Surgical factors

The poorer cosmetic results obtained with quadrantectomy, even in the most experienced hands, compared with wide excision are well documented and are related to the much larger volumes of tissue removed by quadrantectomy.69

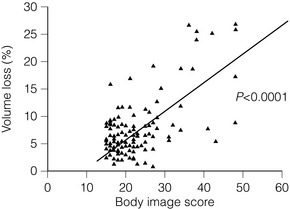

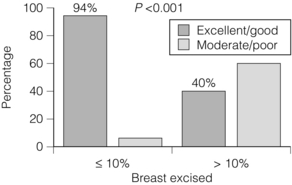

Even more critical than the volume of tissue resected is the percentage volume of the breast excised. There is a highly statistical correlation between cosmetic outcome and percentage volume of the breast excised (Fig. 4.8), with excisions of less than 10% of breast volume generally being associated with a good cosmetic outcome, whereas excisions over 10% often produce a poor cosmetic result (Fig. 4.9). Where it is clear that more than 10% of breast volume needs to be excised in order to remove the cancer, then consideration should be given to one of a number of procedures that can improve the final cosmetic result. These include volume replacement with a myocutaneous or local lipocutaneous flap,12,13 volume replacement using immediate lipofilling following the tumour excision, an oncoplastic reduction procedure (therapeutic mammoplasty), neoadjuvant drug therapy or a mastectomy with or without immediate reconstruction.

Figure 4.8 Percentage of breast excised compared with body image score. Percentage of breast excised calculated by measuring total weight of excision and estimating breast volume (from initial diagnostic craniocaudal mammogram). Body image score based on patient-administered questionnaire of 15 questions (score runs from 15, the best possible score, to 60, the worst and highest possible score). Data from a series of 120 patients treated in the Edinburgh Breast Unit.

Figure 4.9 Percentage of good/excellent results in patients subdivided according to whether 10% or less or more than 10% of breast volume was excised by breast-conserving surgery.

Re-excision and number of procedures

Re-excision of the tumour bed has a negative impact on cosmesis.64 This is mainly as a consequence of the increased total volume of tissue excised from the breast. There is no limit to the number of re-excisions that a patient can have to achieve complete removal of all invasive and in situ disease,70 but with the greater number of re-excisions more tissue is removed and so the likelihood of a good cosmetic result decreases. For patients who require multiple excisions to get clear margins then consideration should be given to correcting any volume deficit prior to delivery of radiotherapy or considering subsequent contralateral symmetrising surgery.

Axillary surgery

Axillary clearance does appear to be associated with a worse cosmetic outcome compared with sentinel node biopsy, primarily because of the volume of tissue removed, which results in an axillary deficit, but also because removing all nodes increases the risk of breast oedema.63,64,71

Breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant therapy

Significant numbers of patients are diagnosed with large or locally advanced breast cancer, many of whom are treated initially by neoadjuvant chemotherapy or endocrine therapy. Up to a half of these patients will subsequently become candidates for breast-conserving surgery. To improve complete excision rates and minimise cosmetic deformity in these patients there are some guiding principles when performing breast conservation surgery after completion of neoadjuvant therapy. First, it is important to know the exact site of the tumour within the breast, as significant numbers of patients with HER2-positive and triple negative cancers will have a complete pathological response. All patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy who might be candidates for subsequent breast-conserving surgery should therefore have one or more tumour markers placed centrally prior to or early during treatment. The patterns of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and neoadjuvant endocrine therapy differ.72 The most common form of pathological change in patients undergoing neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is central scar formation,72 which results in concentric reduction in tumour size and tumour volume. Breast-conserving surgery following neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is therefore usually successful at excising all disease in one operation and few patients have involved margins. In contrast, a significant number of patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a diffuse pattern of response to chemotherapy, with reduction in tumour cellularity but without significant shrinkage of volume. This diffuse tumour may be impalpable and more than 25% of patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy will have incomplete excision of disease. All patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be warned of this rate of incomplete excision and the possible need for a further operation.

Radiotherapy

Increasing doses of radiotherapy, particularly with the addition of boost, have a detrimental effect on cosmetic outcomes.31,63,64 Long-term follow-up is necessary to assess cosmetic outcome; 3 years after treatment, radiotherapy effects tend to stabilise. Fibrosis is a late effect of radiotherapy and produces breast retraction and contour distortion. The treated breast tends not to increase in size to the same extent as the opposite untreated breast, so patients as they age can develop asymmetry even when the initial cosmetic result was excellent. Boost has a negative impact on cosmesis because it produces intense fibrosis and unsightly skin changes, including telangiectasia.31

Other treatment effects

Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors have little if any effect on cosmetic outcome, whereas some studies have suggested that chemotherapy has a negative impact on the cosmetic outcome of breast-conserving surgery.1

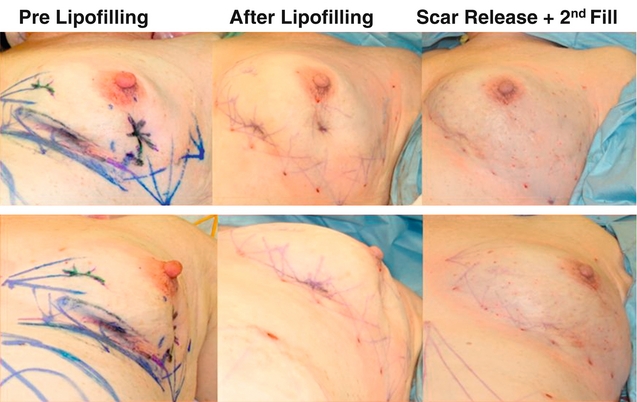

Treatment of poor cosmetic results after breast-conserving surgery

Prevention is better than treatment, so minimising volume, closing breast defects and immediate lipofilling (Fig. 4.10) are much better options than trying to correct asymmetry once it has developed. Options for improving poor cosmetic outcomes include increasing the volume of one or both breasts if the main problem is essentially loss of volume rather than significant radiation fibrosis. While placement of silicone prosthesis or prostheses has been described, they are successful only for patients with little or no deformity and absence of marked skin changes.74 Swelling following implant insertion in a radiotherapy-treated breast is often marked and takes many months to settle. Some patients develop marked capsular contraction after implant placement following radiotherapy but there are no data on whether this incidence is greater than in women having augmentation with no prior radiotherapy. The use of implants has been largely superseded by lipofilling. Fat is aspirated from the abdomen and thighs and centrifuged, washed or filtered.75,76 Having removed the oil and blood it is then injected as microdroplets into the area of distortion and/or asymmetry. Approximately 40% of the injected fat survives. Multiple episodes of lipofilling combined with scar release or scar excision are often required to correct significant breast deformity and asymmetry (Fig. 4.11).76 If the problem is simply one of asymmetry and the treated breast is a satisfactory shape but smaller than the normal contralateral breast, then the contralateral breast can be reduced. If the treated breast is shrunken, misshapen and scarred, then another option is to excise part or the whole of the treated breast and reconstruct either part of the breast or the whole breast. Pedicled myocutaneous latissimus dorsi or transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flaps offer an opportunity to excise unsightly areas of skin and/or breast distortion and scarring, and provide one option to regain symmetry (Fig. 4.12).

Figure 4.10 Result from wide local excision right of a cancer in the upper inner quadrant via a circumareola incision with immediate lipofilling and postoperative radiotherapy.

Significance and treatment of local recurrence

Isolated recurrences of the breast can be treated by re-excision or mastectomy.77–79 Re-excision alone is associated with a high rate of subsequent local recurrence if the initial recurrence occurs within the first 5 years of treatment.78 Until recently 80% of local recurrences in the conserved breast occurred at the site of the original breast cancer, with 90% of these local recurrences following breast-conserving surgery being invasive. This is no longer true and an increasing percentage of ‘recurrences’ in treated breasts are now second primary cancers. Local recurrence within the first 5 years is associated with a worse long-term outlook than recurrence thereafter.7,77–79 The role of systemic therapy following mastectomy for an apparently localised breast recurrence appears to be of benefit.79 Uncontrollable local recurrence is uncommon after breast conservation, but when it does occur it is difficult to treat.

References

1. Sharif, K., Al-Ghazal, S.K., Blamey, R.W., Cosmetic assessment of breast-conserving surgery for primary breast cancer. Breast 1999; 8:162–168. 14731434

2. Al-Ghazal, S.K., Fallowfield, L., Blamey, R.W., Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36:1938–1943. 11000574

3. Shain, W.S., d’Angelo, T.M., Dunn, M.E., et al, Mastectomy versus conservative surgery and radiation therapy: psychological consequences. Cancer 1994; 73:1221–1228. 8313326

4. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1444–1455. 7477144 This review analyses data on 10-year survival from six randomised controlled trails comparing breast conservation with mastectomy. Meta-analysis of data from five of the randomised trials (3006 women) found no difference in the risk of death at 10 years. Where more than half of node-positive patients in both the mastectomy and breast-conserving groups received adjuvant nodal radiotherapy, both groups had similar survival rates. In contrast, where less than half of node-positive women in both groups received adjuvant nodal radiotherapy, survival was better for the breast-conserving surgery group (overall risk vs. mastectomy 0.69, 95% CI 0.5, 90% 0.57). Level I evidence.

5. Morris, A.D., Morris, R.D., Wilson, J.F., et al, Breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy in early stage breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 10 year survival. Cancer J Sci Am 1997; 3:6–12. 9072310 In this review nine randomised controlled trials involving 4981 women potentially suitable for breast-conserving surgery were analysed. Meta-analysis found no significant difference in the risk of death over 10 years for patients treated by mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. The authors also found no significant difference in the rates of local recurrence in the six trials where data were available. Level I evidence.

6. Fortin, A., Larochelle, M., Laverdière, J., et al, Local failure is responsible for the decrease in survival for patients with breast cancer treated with conservative surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17:101–109. 10458223

7. Fisher, B., Anderson, S., Fisher, E., et al, Significance of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence after lumpectomy. Lancet 1991; 338:327–331. 1677695

8. Turnbull, L.W., Brown, S.R., Olivier, C., et al, Multicentre randomized controlled trial examining the cost- effectiveness of contrast-enhanced high field magnetic resonance imaging in women with primary breast cancer scheduled for wide local excision (COMICE). Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(1):1–182. 20025837

9. Mann, R.M., Hoogeveen, Y.L., Blickman, J.G., et al, MRI compared to conventional diagnostic work-up in the decision and evaluation of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: a review of existing literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 107:1–14. 18043894

10. Houssami, N., Ciatto, S., Macaskill, P., et al, Accuracy and surgical impact of MRI in breast cancer staging: systematic review and meta-analysis in detection of multifocal and multicentric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3248–3258. 18474876 This is a review of the accuracy of MRI in breast cancer and shows that MRI has a high sensitivity but poor specificity.

11. Turnbull, L., Brown, S., Harvey, J., et al, Comparative effectiveness of MRI in breast cancer (COMICE) trial: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):563–571. 20159292 This is the only randomised trial of MRI in breast- conserving surgery. This study shows that routine MRI in breast-conserving surgery is not indicated.

12. Dixon, J.M., Venizelos, B., Chan, P., Latissimus dorsi mini-flap: a technique for extending breast conservation. Breast 2002; 11:58–65. 14965647

13. Raja, M.A.K., Straker, V.F., Rainsbury, R.M., Extending the role of breast-conserving surgery by immediate volume replacement. Br J Surg 1997; 84:101–105. 9043470

14. Fisher, E.R., Sass, R., Fisher, B., et al, Pathologic findings from the national surgical adjuvant breast project (protocol 6): relation of local breast recurrence to multicentricity. Cancer 1986; 57:1717–1724. 2856856

15. Kurtz, J.M., Jacquemier, G., Amalaric, R., et al, Breast-conserving therapy for macroscopically multiple cancers. Ann Surg 1990; 212:38–44. 2363602

16. Lim, W., Park, E.H., Choi, S.L., et al, Breast conserving surgery for multifocal breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):87–90. 19106681

17. Gentilini, O., Botteri, E., Rotmensz, N., et al, Conservative surgery in patients with multifocal/multicentric breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(3):577–583. 18330695

18. Ballinger, S., Mayer, K.F., Lawrence, G., et al, Patients’ decision-making in a UK specialist centre with high mastectomy rates. The Breast 2008; 17:574–579. 18793856

19. Holland, D.R., Connolly, J.L., Gelman, R., et al, The presence of an extensive intraductal component (EIC) following a limited excision predicts for prominent residual disease in the remainder of the breast. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8:113–118. 2153190

20. Veronesi, U., Volterrani, F., Luini, A., et al, Quadrantectomy versus lumpectomy for small size breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 1990; 26:671–673. 2144153

21. Ghossein, N.A., Alpert, S., Barba, J., et al, Importance of adequate surgical excision prior to radiotherapy in the local control of breast cancer in patients treated conservatively. Arch Surg 1992; 127:411–415. 1558493

22. Sacchini, V., Luini, A., Tana, S., et al, Quantitive and qualitative cosmetic evaluation after conservation treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 1991; 27:1395–1400. 1835855

23. NIH Consensus Conference, Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA 1991; 265:391–395. 1984541

24. Fisher, B., Wolmark, N., Fisher, E.R., et al, Lumpectomy and axillary dissection for breast cancer: surgical, pathological and radiation considerations. World J Surg 1985; 9:692–698. 4060746

25. Langer, K. Zur anatomie und physiologie der Haut. Huber Die Spaltbarkiet Der Cutis. S-b-Akad Wiss Wein. 1861; 44:19–46.

26. Kraissl, C.J., The selection of appropriate lines for elective surgical incisions. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1951; 8:1–28. 14864071

27. Nedelman, R., Dixon, J.M., Marking of specimens in patients undergoing stereotactic wide local excision for breast cancer. Br J Surg 1992; 79:55. 1737277

28. Singletary, S.E., Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg 2002; 184:383–393. 12433599 Ten-year follow-up of a cohort of patients treated by breast conservation reporting patterns of local, regional and systemic recurrence. Study reports low annual rate of breast tumour recurrence with a ≥ 1 mm margin.

29. Houssami, N., Macaskill, P., Marinovich, M.L., et al, Meta-analysis of the impact of surgical margins on local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(18):3219–3232. 20817513 A meta-analysis of margins that demonstrates that wide margins are unnecessary in breast-conserving surgery. It shows that both involved and close < 1 mm margins are associated with a significant increase in local recurrence. This meta-analysis concludes that a 1-mm margin is sufficient.

30. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10 801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1707–1716. 22019144 A meta-analysis demonstrating the value of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in both reducing recurrence and improving overall survival.

31. Bartelink, H., Horiot, J.C., Poortmans, P., et al, Recurrence rates after treatment of breast cancer with standard radiotherapy with or without additional radiation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1378–1387. 11794170

32. Kurtz, J.M., Factors influencing the risk of local recurrence in the breast. Eur J Cancer 1992; 28:660–666. 1591089

33. Mate, T.P., Carter, D., Fischer, D.B., et al, A clinical and histopathological analysis of the results of conservation surgery and radiation therapy in stage I and stage II breast carcinoma. Cancer 1986; 58:1995–2002. 3019514

34. Zafrani, B., Viehl, P., Fourqhet, A., et al, Conservative treatment of early breast cancer: prognostic value of the ductal in situ component and other pathological variables on local control and survival. Long term results. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989; 25:1645–1650. 2556282

35. Ryoo, M.C., Kagan, A.R., Wollin, M., Prognostic factors for recurrence and cosmesis in 393 patients after radiation therapy for early mammary carcinoma. Radiology 1989; 172:555–559. 2546175

36. Chauvet, B., Simon, J.M., Reynaud-Bougnoux, A., et al, Récidives mammaires après traitment conservateur des cancers du sein: facteurs prédictifs et signification pronostique. Bull Cancer 1990; 77:1193–1205. 2081279

37. Pierce, L., Levin, A., Rebbeck, T., et al. Ten-year outcome of breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and radiotherapy (RT) in women with breast cancer (BC) and germline BRCA 1/2 mutations: results from an international collaboration. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003; 82:S7.

38. Rebbeck, T.R., Lynch, H.T., Neuhausen, S.L., et al, Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1616–1622. 12023993

39. Fowble, B.L., Solin, L.J., Schultz, D.J., et al, 10 year results of conservative surgery and irradiation for stage I and II breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 21:269–277. 1648040

40. Haffty, B.G., Fischer, D., Rose, M., et al, Prognostic factors for local recurrence in the conservatively treated breast cancer patient: a cautious interpretation of the data. J Clin Oncol 1991; 6:997–1003. 2033434

41. Locker, A.P., Ellis, I.O., Morgan, D.A.L., et al, Factors influencing local recurrence after excision and radiotherapy for primary breast cancer. Br J Surg 1989; 76:890–894. 2553196

42. Kurtz, J.M., Jacquemier, G., Amalric, R., et al, Risk factors for breast recurrence in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients with ductal cancers treated by conservation therapy. Cancer 1990; 65:1867–1878. 2156607

43. Asgiersson, K.S., McCulley, S.J., Pinder, S.E., et al, Size of invasive breast cancer and risk of local recurrence after breast-conservation therapy. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39:2462–2469. 14602132

44. Eberlein, T.G., Schnitt, J.S., et al, Predictors of local recurrence following conservative breast surgery and radiation therapy. The influence of tumour size. Arch Surg 1990; 125:771–779. 2161207

45. Jacquemier, R.G., Kurtz, J.M., Amalric, R., et al, An assessment of extensive intraductal component as a risk factor for local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery. Br J Cancer 1990; 61:873–876. 2164836

46. Fourquet, A., Campan, F., Zafrani, B., et al, Prognostic factors of breast recurrence in the conservative management of early breast cancer: a 25 year follow up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989; 17:719–725. 2777661

47. du Toit, R.S., Locker, A.P., Ellis, I.O., et al, An evaluation of differences in prognosis, recurrence patterns and receptor status between invasive lobular and other invasive carcinomas of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol 1991; 17:251–257. 1646127

48. Schnitt, S.J., Connolly, J.L., Kettry, U., Pathologic findings on re-excision of the primary site in breast cancer patients considered for treatment by primary radiation therapy. Cancer 1987; 59:675–681. 3026606

49. Gage, I., Schnitt, S.J., Nixon, A.J., et al, Pathologic margin involvement and the risk of recurrence in patients treated with breast-conserving therapy. Cancer 1996; 78:1921–1928. 8909312

50. Smitt, M.C., Nowels, K.W., Zdeblick, M.J., et al, The importance of the lumpectomy surgical margin status in long term results of breast conservation. Cancer 1995; 76:259–267. 8625101

51. Solin, L.J., Fowble, B.L., Schultz, D.J., et al, The significance of the pathology margins of the tumour excision on the outcome of patients treated with definitive irradiation for early stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 21:279–287. 1648041

52. Spivack, B., Khanna, M.M., Tafra, L., et al, Margin status and local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery. Arch Surg 1994; 129:952–957. 8080378

53. Wazer, D.E., Jabro, G., Ruthazer, R., et al, Extent of margin positivity as a predictor for local recurrence after breast conserving irradiation. Radiat Oncol Investig 1999; 7:111–117. 10333252

54. Schmidt-Ullrich, R., Wazer, D.E., DiPetrillo, T., et al, Breast conservation therapy for early stage breast carcinoma with outstanding ten year locoregional control rates: a case for aggressive therapy to the tumour bearing quadrant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993; 27:545–552. 8226147

55. Vallasiadou, K., Young, O.E., Dixon, J.M. Current practices in breast conservation surgery: results of a questionnaire. Br J Surg. 2003; 90:44.

56. Montgomery, D.A., Krupa, K., Jack, W.J.L., et al, Changing pattern of the detection of locoregional relapse in breast cancer: the Edinburgh experience. Br J Cancer 2007; 96:1802–1807. 17533401

57. Abner, A.L., Connolly, J.L., Recht, A., et al, The relation between the presence and extent of lobular carcinoma in situ and the risk of local recurrence for patients with infiltrating carcinoma of the breast treated with conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer 2000; 88:1072–1077. 10699897

58. Fowble, B., Hanlon, A.L., Patchefsky, A., et al, The presence of proliferative breast disease with atypia does significantly influence outcome in early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with conservative surgery and radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 42:105–115. 9747827

59. Swanson, G.P., Rynearson, K., Symmonds, R., Significance of margins of excision on breast cancer recurrence. Am J Clin Oncol 2002; 25:438–441. 12393979

60. Rose, M.A., Henderson, I.C., Gellman, R., et al, Premenopausal breast cancer patients treated with conservative surgery, radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy have a low risk of local failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989; 17:711–717. 2777660

61. Goss, P.E., Ingle, J.N., Martino, S., et al, A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1793–1802. 14551341

62. Forrest, P., Stewart, H.J., Everington, D., et al, Randomised controlled trial of conservative therapy for breast cancer: 6-year analysis of the Scottish trial. Lancet 1996; 348:708–713. 8806289

63. Prosnitz, L.R., Goldenberg, I.S., Packard, R.A., et al, Radiation therapy as initial treatment for early stage cancer of the breast without mastectomy. Cancer 1977; 39:917–923. 402202

64. Wazer, D.E., DiPetrillo, T., Schmidt-Ullrich, R., et al, Factors influencing cosmetic outcome and complication risk after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10:356–363. 1445509

65. Dewar, J.A., Benhamou, S., Benhamou, E., et al, Cosmetic results following lumpectomy, axillary dissection and radiotherapy for small breast cancers. Radiother Oncol 1988; 12:273–280. 3187067

66. Liljegren, G., Holmberg, L., Westman, G., et al, The cosmetic outcome in early breast cancer treated with sector resection with or without radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer 1993; 29A:2083–2089. 8297644

67. Haffty, B.G., Wilson, L.D., Smith, R., et al, Subareolar breast cancer: long-term results with conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 33:53–57. 7642431

68. Petit, J.Y., Garusi, C., Greuse, M., et al, One hundred and eleven cases of breast conservation treatment with simultaneous reconstruction at the European Institute of Oncology. Tumori 2002; 88:41–47. 12004849

69. Amichetti, M., Busana, L., Caffo, O., Long-term cosmetic outcome and toxicity in patients treated with quandrantectomy and radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncology 1995; 52:177–181. 7715900

70. Coopey, S., Smith, B.L., Hanson, S., et al, The safety of multiple re-excisions after lumpectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3797–3801. 21630123

71. Sneeuw, K.A., Aaronson, N., Yarnould, J., et al, Cosmetic and functional outcomes of breast conserving treatment for early stage breast cancer. 1. Comparison of patients’ ratings, observers’ ratings and objective assessments. Radiother Oncol 1992; 25:153–159. 1470691

72. Thomas, J.S., Julian, H.S., Green, R.V., et al, Histopathology of breast carcinoma following neoadjuvant systemic therapy: a common association between letrozole therapy and central scarring. Histopathology 2007; 51:219–226. 17650216

73. Manton, D.J., Chaturvedi, A., Hubbard, A., et al, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: early response prediction with quantitative MR imaging and spectroscopy. Br J Cancer 2006; 94:427–435. 16465174

74. Schaverien, M.V., Stutchfield, B.M., Raine, C., et al, Implant-based augmentation mammaplasty following breast conservation surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69(3):240–243 Feb 21. Epub ahead of print. 21346535

75. Delay, E., Garson, S., Tousson, G., et al, Fat injection to the breast: technique, results and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthetic Surg J 2009; 29:360–376. 19825464

76. Rigotti, G., Marchi, A., Stringhini, P., et al, Determining the oncological risk of autologous lipoaspirate grafting for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2010; 34:475–480. 20333521

77. Haffty, B.G., Fischer, D., Beinfield, M., et al, Prognosis following local recurrence in the conservatively treated breast cancer patient. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 21:293–298. 2061106

78. Kurtz, J.M., Jacquemier, G., Amalric, R., Is breast conservation after local recurrence feasible. Eur J Cancer 1991; 27:240–244. 1827303

79. Anderson, E.D.C. Treatment of breast recurrence after breast conservation. In: Dixon J.M., ed. Breast cancer: diagnosis and management. London: Elsevier; 2000:1–5.