CHAPTER 10 Breast Cancer

For the majority of women with breast cancer, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has become a standard part of their treatment and healing.1

THE BREASTS AND THE BREAST EXAM

ANATOMY OF THE BREASTS

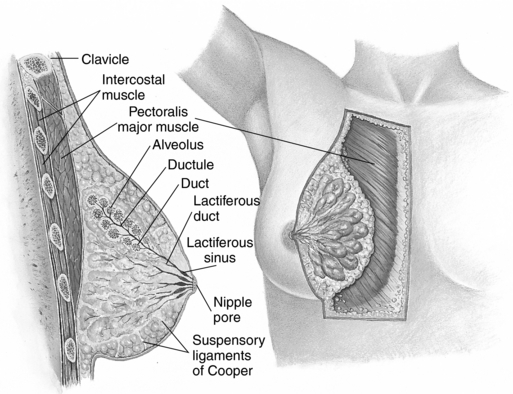

The breasts of an adult woman are tear-shaped mammary glands (Fig. 10-1), technically developmentally modified sweat glands with the potential for milk production. A layer of subcutaneous adipose tissue surrounds the glands and extends throughout the breast itself, comprising 80% to 85% of the normal breast. The breasts are supported by and attached to the pectoral muscles of the thorax by ligaments. Each breast contains 12 to 25 circularly arranged lobes radiating around the nipple. Each lobe is comprised of numerous lobules containing clusters of alveolar glands that produce milk in a lactating woman. The alveolar glands transport the milk into lactiferous ducts that drain its respective lobe. Each lactiferous duct widens to form an ampulla, and then narrows prior to termination at openings in the nipple. A band of circular smooth muscle surrounds the base of the nipple, whereas longitudinal smooth muscle fibers extend this ring, encircling the lactiferous ducts as they converge toward the nipple. The adipose tissue and configuration of lobes determine the size and shape of the breast.

Figure 10-1 Anatomy of the female breast.

Seidel HM: Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.

The darker-pigmented area around the nipple is called the areola. Its size and color varies from 2 to 6 cm in diameter and from pale pink to deep brown depending on age, parity, and skin pigmentation. The areola contains numerous small oil-producing glands called Montgomery’s tubercles, which serve to lubricate the areola and become more pronounced during pregnancy.3

Women’s breast shape, size, and “tone” are as highly variable as are women themselves. Yet, because of a narrow range of acceptable breast appearance in Western culture, many women are dissatisfied with their breasts. According to the American Society for Plastic Surgery, nearly 250,000 breast augmentation procedures were performed in 2005. Breast augmentation for teenagers accounted for 3841 procedures in 2003. The number of breast augmentations increased 7% from 2002 to 2003. When physicians were asked the primary reason, their patients offered for wanting a breast augmentation, 91% said it was to improve the way they feel about themselves.4

CYCLIC INFLUENCES ON BREAST TISSUE

During pregnancy, in response to progesterone, breast size and turgidity increase significantly, accompanied by deepening nipple and areolar pigmentation, nipple enlargement, areolar widening, and an increase in the number and size of Montgomery’s tubercles. In response to hormonal signals, the alveoli enlarge and their lining cells, the acini cells, increase in number and size (hyperplasia and hypertrophy). The breast ductal system branches markedly. In late pregnancy, the fatty tissues of the breasts are almost completely replaced by cellular breast parenchyma. Secretion of colostrum may begin during pregnancy. After birth, the fully mature breasts secrete milk in response to prolactin.

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is perhaps the single most important medical concern women face today. Although there has been an overall decrease in breast caner rates in the United States in recent decades, in 2007 there were greater than 180,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 40,910 breast cancer-related deaths. This is equivalent to a breast cancer diagnosis every 2 minutes.2 Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer in women, accounting for one-third of all cancer cases.3 All women are affected by breast cancer—whether by literal diagnosis or a lifetime of worry about whether they will experience this disease.2 It has been estimated that 50% of all women in the United States at some point in their lives will ask their physicians about a concerning lump or other worrisome breast finding with the anxiety that they have breast cancer. Many have known a friend, relative, or colleague who has gone through a possible or actual breast cancer diagnosis.

RISK FACTORS FOR DEVELOPING BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is the result of the complex interaction of multiple factors—hormonal, genetic, environmental, and lifestyle.2 Breast cancer risk factors can be divided into nonmodifiable and modifiable risks. The former are heritable or genetic, although it is arguable that genetics can be favorably or negatively influenced by either beneficial or harmful environmental exposures, diet, and therapies that target genetic processes such as transcription and tumor suppression, and thus to some extent, may be modifiable. Modifiable factors include diet, obesity, alcohol intake, and environmental exposures.

GENETICS

Germ line mutations are responsible for no greater than 10% of human breast cancers.3 However, women with specific mutations have a much higher lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, are more likely to experience breast cancer at an earlier age than the average population, and may experience more severe forms of the disease, BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 are known as tumor suppressor genes. Women who have inherited a mutated BRCA-1 allele from either parent have a 60% to 85% lifetime likelihood of developing breast cancer (as well as a 33% chance of developing ovarian cancer). Women with this gene born after 1940 have an even higher risk, attributed to increased exposure to cancer-promoting environmental factors, and Ashkenazi Jewish women have an increased likelihood of carrying this mutation.3 Mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene, such as occurs in the inherited Li-Fraumeni syndrome, is associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer and other cancers, as are PTEN tumor suppressor mutations. Heightened oncogene expression is seen in approximately 25% of breast cancer cases. Erb-2 (HER-2 neu), a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) superfamily, is a product of oncogene overexpression, and can contribute to malignant transformation of human breast epithelium.3 Women with a genetic cancer predisposition are considered high risk for breast cancer and may receive recommendations for prophylactic cancer treatment including oophorectomy, elective mastectomy, and chemotherapy with tamoxifen, raloxifene, and/or aromatase inhibitors, discussed in the following.2

Endogenous Hormone Exposure

Breast cancer is a hormone-dependent disease manifesting as a malignant proliferation of clonal epithelial cells lining the ducts or lobules of the breast.3 Its hormonal dependence is demonstrated by the fact that women who lack functioning ovaries and who never received hormone replacement (HR) do not develop breast cancer. Women are 150 times more likely to develop breast cancer than are men because of their greater exposure to estrogen and progesterone.3 Although women may develop breast cancer at any age, there is a slight decline in breast cancer incidence after menopause accompanying naturally declining levels of estrogen and progesterone; however, statistically, as women age they have an increasing likelihood of being diagnosed with breast cancer, likely as a result of a lifetime of accumulated exposures (0.4% chance of diagnosis between 30 and 40 years of age; 4% chance between the ages of 70 and 80 years).3,4

Three life cycle events appear to significantly influence a woman’s overall risk of developing breast cancer: age at menarche, age at first pregnancy, and age at menopause. Women who begin to menstruate at age 16 have 50% to 60% of the risk of developing breast cancer compared with those who experience menarche at age 12.3 Having a full-term pregnancy by age 18 confers a 30% to 40% lower risk of developing breast caner compared with women who have no children, and menopause (natural or surgical) that occurs 10 years prior to the median age of 52 years old for menopause decreases lifetime breast cancer risk by approximately 35%.3 Breastfeeding duration has been shown by meta-analysis to also confer substantial protection against breast cancer regardless of age at first pregnancy or number of pregnancies.3 The risk reduction is directly correlated with a decreased amount of time during which breast tissue is exposed to endogenous estrogens. International variation in breast cancer rates has also supported the role of hormonal exposure as an etiologic factor in breast cancer. Asian women, for example, have been found to have significantly lower serum estrogen and progesterone levels, and have breast cancer rates of 10% to 20% of women in westernized nations (see discussion on diet and phytoestrogens).

Alcohol Intake

Even modest amounts of regular alcohol consumption (e.g., one glass of wine daily) has been associated with a 26% increased risk of breast cancer on the basis of multiple cohort studies.2,3 Folic acid supplementation may modify this risk somewhat.3 The risk of breast cancer needs to be weighed against the cardioprotective effects of modest alcohol intake.3

Dietary Fat Intake and Obesity

Dietary fat intake has been a focus of much research and debate. The dietary fat hypothesis, which proposed a correlation between amount of dietary fat intake and breast cancer incidence, is based on the observation that national per capita fat consumption is highly correlated with breast cancer mortality rates. However, per capita fat intake is also associated with economic prosperity, and this is accompanied by other factors that are also related to breast cancer risk, such as early menarche, low parity, later age at first birth, and lower levels of physical exercise.5 Studies have failed to show a direct correlation between consumption of specific types of dietary fats, or the amount of fat in the diet, and breast cancer.6 However, excessive caloric intake from any source in adolescent girls has been shown to lead to earlier menarche, whereas in older women can delay the onset of menopause, which as discussed are risk factors for breast cancer development.3

Obesity has been correlated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in women.7 Postmenopausal weight gain and obesity have been shown to increase breast cancer risk by as much as 50%.2 Increased risk results from prolonged and increased aromatase activity in the adipose tissue leading to increased conversion of fat to estrogen.2,3,7 As many as 20% of all postmenopausal breast cancers and 27% of all cancers in women over 70 years of age may be attributable to obesity or moderate to significant weight gain after the fifth decade of life, and up to 50% of all postmenopausal deaths resulting from breast cancer may be attributable to obesity.7 Obesity is also a risk factor for poor breast cancer prognosis with larger tumor size, greater risk of metastases, poorer surgical outcome, and less efficient response to chemotherapy and radiation. The Cancer Prevention Study II concluded that as many as 18,000 deaths of women in the United States over 50 years old could be prevented if women maintained a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 throughout adulthood.7 Weight loss and maintenance of weight in the BMI ranger of 19 to 25 kg/m2 has been shown to reduce breast cancer risk by about 30%.2

Environmental Hormone Exposure

Exogenous hormone exposure may play a significant risk in the etiology of breast cancer. There is well-supported evidence that many commonly used chemicals and widespread environmental pollutants act as hormone disruptors.8 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), in conjunction with certain genetic polymorphisms involved in carcinogen activation and steroid hormone metabolism, cause mammary gland tumors in animals specifically by mimicking estrogen, or increasing susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis.9 Evidence regarding dioxins and organic solvents is sparse and methodologically limited but also suggestive of an association between breast cancer and exposure.9 Scientist Rachel Carson suggested the role of environmental contamination in human cancers several decades ago, however, it is only in recent years that the role of exogenous hormones acting as hormone disruptors has begun to be seriously studied, and a great deal is unknown.

Although older studies suggested an association between oral contraceptive (OC) use and breast cancer, more recent meta-analyses imply little to no breast cancer risk from their use.2,3 The Women’s Health Initiative trial found a correlation between risk of breast cancer (and increased cardiovascular risk) and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), particularly with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus progestins. Further, women with a prior breast cancer diagnosis have an increased rate of recurrence with HRT.3 Minimizing unnecessary human exposure to known endocrine disruptors and other carcinogens should be high on our national medical and environmental research budgets.

Prior Radiation Exposure

Women with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were treated with thoracic radiation have a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer caused by exposure.2

Lifetime vs. Age-Adjusted Risk of Developing Breast Cancer

The figure that one in eight women will develop breast cancer is slightly misleading and may create unnecessary fear in women. Based on statistics from 2002 to 2003 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), 12.7% will be diagnosed with cancer in their lives, and it is from this figure that the “one in eight” statistic is derived. However, lifetime risk is a cumulative average and does not reflect a woman’s risk at different ages. The age-adjusted risk gives women a more realistic, although still generalized, picture of their risk of developing breast cancer. According to the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results statistics (http://seer.cancer.gov/), a woman’s chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer is:

Of course, as discussed, many more factors than gender, age, and nationality contribute to breast cancer risk. To adjust for such factors as genetics, weight, and lifestyle, a number of statistical tools have been devised to calculate what might be closer to actual risk for any individual woman. The most widely used scale is the Gail model, which is available as a risk calculator via the National Cancer Institute website at http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/for individuals and practitioners to use.2,10,11 The tool is not a valid method of calculating breast cancer or recurrence risk in women who have already had a diagnosis of breast cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). One research group suggests that another model, the Rosner and Coldiz model, more accurately classifies women according to their risk stratification; however, it is not as widely used as the Gail model.11

Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status have been associated with delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, and therefore may contribute to poorer outcomes. Breast cancer outcomes are also worse for uninsured and Medicaid patients than for privately insured patients.12

Breast Cancer in Pregnancy

During pregnancy breast tissue is stimulated by increased levels of estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and human placental lactogen (HPL).3 Breast cancer occurs at a rate of 1/3000 to 4000 pregnancies. Pregnant or lactating women should have any persistent breast or axillary lumps evaluated by a gynecologist. Too often breast lumps in this population are dismissed by women or health care professionals as the result of hormonal changes, unfortunately sometimes leading to detection of breast cancer only once it has become advanced.

CONVENTIONAL RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Conventional breast cancer risk reduction strategies include:2

Surveillance

Breast Self-Exam

A recent review by the Cochrane group, the results of several large randomized trials, and a review by the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) all concluded that breast self-exam (BSE) does not reduce breast cancer specific mortality, and in fact, may increase the number of unnecessary biopsies women receive for benign findings.4 Nonetheless, it is a noninvasive method that some women find self-empowering or reassuring to perform, and which may sometimes lead to the early detection of breast cancer.3 Women should be informed about the potential risk of BSE findings leading to unnecessarily invasive testing and they should be taught to perform the BSE correctly to maximize the value of the exam.

Breast cancer is a leading cause of death in American women. Overall exposure to circulating and environmental estrogens, lifestyle factors, and genetic predisposition may all contribute to breast cancer development. The clinical practitioner should include a thorough breast exam as part of routine gynecologic care. It is a simple technique, and when done properly, can be an important part of overall cancer screening. In recent years, the value of the BSE has come under scrutiny, and large trials suggest that it is not helpful in reducing cancer mortality and may actually contribute to an overall higher rate of unnecessary breast biopsies. It is clear that if women wish to perform BSE, they should be taught to do so correctly. The Susan E. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation website (http://www.komen.org/bse/) offers a valuable video demonstration on the proper techniques for BSE, relevant to the health practitioner and patient alike. Additionally, numerous other websites provide invaluable resources on BSE for patients and care providers. The following discussion provides very general guidelines for BSE.

When to Perform a Breast Self-Exam

In 80% of all cases, breast lumps and changes do not signal breast cancer. However, women should report all unusual changes (Box 10-1) to their health care provider and seek a clinical evaluation. Many women put off telling their doctor out of fear. It can be reassuring for patients to know that at least 50% of all women will seek evaluation for a suspicious lump or breast change at some point in their life.

BOX 10-1 Breast Self-Exam

Breast Changes and Warning Signs

Differentiating Breast Lumps by Palpation

WARNING: A physician should evaluate persistent lumps or abnormalities as soon as possible.

Performing the Breast Self-Exam

Breast self-examination requires examining the entire chest area and both breasts, as well as the axillary area. Although it does not matter in what order the steps of the BSE are performed, it is essential that all steps be performed so that no area remains overlooked. Therefore, women should perform the BSE systematically each time. A log or journal, with an entry after each exam, can help a woman keep track of her findings, and can help her to objectively track any changes she might notice. The instructions that follow are adapted from the American Cancer Society.

General Rules

Although cancerous growths are most likely to be found in the upper, outer breast quadrant or behind the nipple, they can occur in any area of the breast, chest, or lymph network (Box 10-2); therefore, a thorough exam is essential.

Step 1: Breast Self-Exam While Lying Down

Lie down with a pillow or folded towel under the right shoulder and place the right arm behind the head (Fig. 10-3). Check the entire breast and armpit area using the pads of the first three middle fingers on the left hand to feel for lumps, changes, or irregularities in the right breast.

Figure 10-3 Exam lying down

Seidel HM: Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.

Step 2: Breast Self-Exam Upright and Front of a Mirror

The upright position (Fig. 10-4) can facilitate examining the upper and outer portions of the breasts and armpit. The lying down portion can either precede or proceed the upright portion. Both a lying down and an upright exam should be performed at each monthly BSE. Examining the breasts in front of a mirror allows women to check for changes in shape, direction, or texture of the breasts. It should be done in a warm area with good lighting. The mirror should allow inspection of the torso from the waist to the neck.

Clinical Breast Exam

The clinical breast exam (CBE) is an important but often overlooked or deferred part of the routine physical exam. The clinical breast exam makes a small but important contribution to breast cancer detection, with approximately 5% to 10% of breast cancers identified solely by CBE, independent of mammography.4 As with BSE, CBE should be properly performed using a vertical technique to maximize the likelihood of finding abnormal breast changes, and the breasts should be visualized with the woman in a variety of designated positions. One study reported that variations in CBE technique led to a 29% variation in sensitivity and a 33% variation in specificity.4 The most important aspect of the CBE contributing to sensitivity is the amount of time taken to perform the exam.4

Mammography MRI, and Ultrasound

Numerous RCTs performed since the 1960s have demonstrated decreased risk of breast cancer death in women randomized to receive mammography. Although a well-publicized meta-analysis questioned the value of mammography as a breast cancer screening test based on flaws identified in earlier studies, further meta-analysis by the USPSTF concluded that these flaws did not significantly affect outcomes, and recommended screening mammography every 1 to 2 years for women over 40 years of age and annually for women over age 70 with no comorbidities that that decrease life expectancy.4, 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Screening mammography is associated with reduced size and stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. Sensitivity is estimated to be between 60% and 90%.4 Many mammography testing facilities have begun to use computer-aided detection systems designed to assist radiologists in interpreting; however, recent research has found that these tools actually decrease sensitivity and increase false positive results, and since their introduction, breast cancer detection rates have not changed substantially.4,22 There is no greater benefit to annual mammograms compared with every 2 years in women under 70 unless they are high risk for breast cancer or breast cancer recurrence.13 High-risk women with a family history of breast cancer should begin screening when they are 10 years younger than the age at which their youngest relative to be diagnosed with breast cancer received a diagnosis. No trials to date have evaluated an age end point for screening mammography. Two trials have enrolled women over age 65; none have evaluated mammography in women over age 74 years.13

Mammography is the only imaging method that has been demonstrated through RCTS to be effective for breast cancer screening. Current recommendations call for screening mammography every 1 to 2 years beginning at age 40 for low-risk women, and annual screening for women over 70 in the absence of comorbid disease that lowers life expectancy.13

The risk of radiation exposure associated with mammography is of concern to many women. The Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR V) review estimated that the potential total annual added risk of breast cancer mortality resulting from mammography (300 mrad for two-view examination of both breasts) to be 41.9/100,000 for women age 25, 30.9/100,000 for women age 30; 21.4/100,000 for women age 35; 13.8/100,000 for women age 40; and 3.9/100,000 for women age 50 compared with an estimate of greater than 3000 deaths that would occur as a result of naturally occurring breast cancers among women who do not receive screening mammography. 23 24 25

Concerns have also been raised about the possible short- and long-term detrimental effects of false positive mammograms on women’s psychoemotional well-being. Based on a recent systematic review, a false-positive mammogram does increase anxiety, sometimes substantially, but usually only short-term, and may actually lead women in the United States to increase their diligence about receiving breast screening in the future.26

Mammography is less sensitive and results in a reduction of breast cancer–related deaths in younger women, likely a result of greater breast tissue density in younger women as well as faster rate of cancer growth.4 For women with dense breasts, particularly women under 30, screening ultrasound is commonly recommended; however, the European Group for Breast Cancer Screening concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of screening ultrasound at any age.27 In contrast, a prospective, uncontrolled study of 11,130 women with dense breasts screened with mammography, clinical examination, and bilateral whole breast ultrasound over approximately 2 years, screening breast ultrasound increased the number of women diagnosed with nonpalpable invasive cancers by 42%.28 Another option is digital mammography which may be more sensitive in women under 50 with dense breasts; however it is expensive and not widely available.22,28

Recently MRI has been receiving attention as a breast cancer detection tool owing to its greater sensitivity in detecting breast cancer in high-risk women, and its ability to increase earlier diagnosis.4 MRI, however, is also associated with a higher rate of false-positives than is mammography, and it is costly. The latest American Cancer Society recommends screening MRI in addition to mammograms for women who meet at least one of the following conditions:29

Risk-Reducing Surgery

Although this is an aggressive option, risk-reducing surgery may be reasonable for women with a high risk hereditary predisposition to breast cancer. Prophylactic oophorectomy may be the preferred primary strategy for risk reduction prior to mastectomy as it is effective and is not associated with visible physical alteration and thus can spare women struggles with body image that accompany mastectomy.2 Surgical menopause before age 35 is established as protective against breast cancer; however, it is also a risk factor for osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.10

Chemoprevention

It should be noted that no chemopreventative strategy to date has demonstrated increased health or survival benefits.2 Tamoxifen and raloxifene will only reduce the incidence of estrogen receptor positive cancers, and have no effect on estrogen receptor negative cancer.10 Side effects can be considerable and often make it difficult to complete the 5-year course of prophylactic treatment. Nonetheless, these drugs have shown significant chemopreventive effects.

Tamoxifen

In 1998, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tamoxifen, a first-generation SERM with both estrogenic and antiestrogenic effects, as an effective breast caner prophylactic agent at a does of 20 mg/d for 5 years. Its estrogen receptor blocking effects make it effective against breast cancer.2 Four prospective randomized trials and one meta-analysis of prophylactic tamoxifen use demonstrated a significant reduction in breast cancer occurrence at rates of 43% to 69% in women across all age groups, and also reduces risk of second primary and contralateral breast cancer.2,10,11 However, there was no mortality benefit in any of the trials’ use of the drug is associated with both mild and serious adverse effects, including hot flashes, vaginal discharge, endometrial cancer (2 per 1000 women per year), stroke (doubled risk), and life-threatening thromboembolic disease (double to triple the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism).10 These risks are most prevalent in postmenopausal women and those with comorbidities.2

Raloxifene

Raloxifene is a second-generation SERM with mechanisms of action similar to tamoxifen, but which does not produce endometrial proliferation to the extent as tamoxifen and therefore does not carry the same risk of causing endometrial cancer, although otherwise its side effect profile is similar to tamoxifen.2,10,11 Women taking raloxifene may also experience dyspareunia, weight gain, and musculoskeletal problems compared with those taking tamoxifen; however, those in the latter group are more likely to experience more vasomotor symptoms and leg cramps, although they report improved sexual functioning.2 Raloxifene increases bone mineral density in postmenopausal women and is FDA approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis (see Chapter 18), an advantage for those women taking it prophylactically for breast cancer risk. Raloxifene is not recommended for premenopausal women.2,11

Aromatase Inhibitors

Conversion of androgens to estrogen in peripheral adipose and muscular tissue is called aromatization. At menopause, when the ovaries cease to produce significant quantities of estrogen, aromatization becomes the primary source of estrogens in postmenopausal women. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are used to reduce this process and substantially reduce breast tissue estrogen exposure. At present, they have been studied only as adjuvant therapies for breast cancer treatment; no RCTs have been completed for breast cancer prophylaxis at the time of this writing.2

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic Imaging

Abnormal radiographic findings include clustered microcalcifications, densities, or architectural distortions.3 If a radiologic abnormality is detected, this should be considered contextually. If it is a nonpalpable lesion with a low index of suspicion in a low-risk woman, a follow-up mammogram in 3 to 6 months is considered reasonable.3 If a probably benign lesion is identified, a stereotactic core or surgical biopsy may be recommended, and if the lesion is clearly suspicious, a surgical biopsy is usually performed.3

Staging

Breast cancer staging is based in the TNM (tumor-node-metastasis) model and guides not only diagnosis, but treatment strategies as well. Tumor refers to the histological classification of the lesion and determines the type and severity of the tumor (grading); node refers to the number of lymph nodes involved. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is an importance advance in node staging, sparing women invasive lymph surgery when possible. Metastases refers to the number of tumor sites, and distance from the primary tumor. Additionally, the presence of hormonally positive or negative receptors is determined. Comprehensive cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines, including breast cancer staging, are available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf.

Prognosis

There are numerous prognostic variables in breast cancer. Tumor staging is considered the most important of these. Additional variables include:3

Patterns of tumor gene expression are increasingly being recognized as significant in breast cancer prognosis, and certain patterns may reliably predict disease free internals and survival more accurately than any other prognostic variables.3

CONVENTIONAL BREAST CANCER TREATMENT

The mainstays of conventional cancer treatment include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and endocrine treatment. Breast cancer treatment is highly complex and well beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss. Readers are referred to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (Box 10-4) for 2008 recommended breast cancer treatment guidelines. Women undergoing treatment require a central care coordinator and a strong support network.

CAM BREAST CANCER TREATMENT

How Many Women Are Turning to CAM for Breast Cancer Treatment?

Estimates are that between 34% and 60%, but as many as 83% of cancer patients use some form of CAM, with an estimated out-of-pocket cost of up to $7200/year in the United States.1, 30 31 32 33 Women with breast cancer use more CAM than individuals with other types of cancer, and more CAM therapies than women who do not have cancer.32,34 In one study of CAM use among women with breast cancer, 72% of CAM users used two or more CAM approaches, 49% used three or more, and 15% used seven or more CAM approaches, including prayer/spiritual healing and psychotherapy/support groups.35 Herbs, vitamins, massage, acupuncture, homeopathy, and mind–body healing, are among the therapies frequently used. Most women use complementary therapies in conjunction with conventional medical cancer treatment, although about 2% of women with breast cancer may choose to forego conventional therapy completely and use alternative therapies only.36

Why Women are Choosing CAM Cancer Therapies

The primary reasons women cite for CAM use include desire to enhance their chance of survival, reduction of risk of disease recurrence, relief of disease symptoms, relief from psychological distress, enhancement of immunity, minimization of conventional treatment related side effects, and improvement of quality of life.31,34,37 Some women report that CAM use gives them a feeling of hope and a sense of greater control over their life.1,34 Increasing interest in CAM may also partially be a result of the limitations of conventional breast cancer treatment.35

Desperation can be a motivator toward CAM use, with cancer patients wanting to explore every possible option at their disposal.38 The fear and confusion wrought by a breast cancer diagnosis, and the hope of finding a cure, can make women vulnerable to trying therapies that have no basis of safety or efficacy, and which may be ineffective at best, and costly and/or dangerous at worst.

Several studies have found that women who use CAM therapies as part of their breast cancer treatment plan are more likely to have higher levels of psychosocial stress and anxiety and to report poorer quality of life than those who choose conventional treatment alone.34 This is a perplexing finding with several possible explanations. For example, women who use CAM therapies may be more personally reflective about their stresses, because it has been found that CAM users tend to be more spiritually involved in their illness and tend to try to gain a deeper holistic view of their illness than non-CAM users.34 Women who self-medicate with various herbs or nutrients in addition to conventional therapy also may have previously undetected underlying disorders, such as women taking St. John’s wort may have previously undiagnosed depression. Women who experience more psychological distress associated with their illness may be self-selective for CAM, which is seen as more supportive in nature than conventional care.34

The Complexity of Choosing CAM Therapies

In spite of the widespread use of CAM therapies among women with breast cancer, these therapies remain largely marginalized from mainstream cancer care. This appears to result from lack of a strong evidence base for many of the therapies leading to concern over the risks of therapies and how they might interact or interfere with conventional treatments, and also to differences in how healing is conceptualized and quantified by conventional and CAM practitioners.1,34 Lack of scientific evidence available on CAM therapies means that patients wishing to incorporate CAM into their care are left to rely on hearsay, Internet information, or anecdotal evidence. An Internet search for cancer and either complementary or alternative medicine yields more than 3.4 million websites.36 Distinguishing accurate from unreliable information is nearly impossible for even the educated patient.33 Many women ultimately do their own extensive medical literature research, which is difficult and time consuming for a lay person, and even there, the evidence is limited, confusing, and contradictory. This is frequently an exhausting and frustrating process on top of the emotional and physical toll of dealing with breast cancer and treatment, and many women find they have to turn to family or friends to help them with the burden of research. This may compound a sense of helplessness or conflict.

Available information on CAM and breast cancer is often contradictory, both regarding its safety and value, causing tremendous confusion. Further, because many oncologists and other physicians remain skeptical about the use of CAM in cancer care, women experience a gap between their conventional care and their desire to use CAM, or their actual use, that can lead to inner conflict and tension as an added burden in their care, and this stress may not be insignificant.1 As a result, many women who wish to use CAM therapies, either to enhance their conventional treatment, support their immunity, or mitigate side effects of conventional therapies often forego CAM therapies while they are undergoing conventional treatment out of fear of harmful effects, particularly with chemotherapy.1 Significantly, as many as 64.5% of patients do not disclose CAM use to their health care providers.31 Reasons for this include fear of disapproval from the practitioner, patient perception that the practitioner lacks knowledge of CAM therapies and therefore there is no reason to discuss them, lack of expressed practitioner interest in the patient’s possible use of CAM, and patient perceptions that herbs and supplements are not medications and therefore have no bearing on medical treatment.39

Given women’s desire to include CAM in their breast cancer treatment plans, it is essential that oncologists and other members of the oncology care team be articulate in CAM options, helping women to navigate the complex and overwhelming array of available options, some of which may be beneficial, and many others which may be harmful, or at least be open to the conversation in order to honor their patient’s desire to incorporate CAM into their care. It has been suggested that due to their widespread use, access to CAM therapies should be part of standard oncology treatment.31 What is currently needed are models that bridge the gap between CAM and conventional therapies, allowing for an integrated, interdisciplinary model of care that allows women to comfortably and safely access and incorporate a variety of beneficial and safe treatment modalities into their breast cancer care while relieving women with breast cancer of the onus of responsibility for obtaining and deciphering all of their treatment information.1

Mistrust Between Conventional and CAM Practitioners

There is generally an enormous gap of mistrust separating oncologists and CAM practitioners. Alternative practitioners base their mistrust of conventional physicians and practices on the historical precedence of the evolution of conventional medicine in the United States and the subsequent marginalization of nonconventional practitioners, combined with a general mistrust of cancer treatments that have historically sometimes proved to be as harmful as they have been helpful.39 Conventional practitioners maintain a mistrust of CAM practitioners and products in a milieu in which CAM is widely available and unregulated, allowing just about anyone to put up a shingle or market a product offering the hope of a cancer cure.39 This latter environment is also highly problematic for those CAM practitioners who do possess substantial knowledge and training, but who remain unregulated because of lack of available credentialing pathways in the United States, and are thus categorically lumped into being labeled as quacks or “snake oil salesmen” rather than being integrated into the oncology care team.39

Incidence of Botanical Medicine Use for Breast Cancer

A survey conducted at eight clinical sites of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) found that the most frequently used CAM therapies were herbs and/or vitamins, with 62% of women surveyed using them. Fewer than 53% of women discussed herbal use with their physicians, and fewer than a third considered herbal products to be medications.31

Limitations in Botanical Breast Cancer Treatment Research

Although many studies using botanical products have had promising results, none have definitively demonstrated altered disease progression in patients with breast cancer.37 Because of a bias against unconventional cancer therapies, funding and publishing of studies on CAM cancer therapies, including herbs, historically has been limited. Lack of involvement of nonconventional practitioners in research on herbs, either owing to exclusion by mainstream research institutions or lack of CAM practitioner training in research methodologies, may lead to studies that do not reflect the actual clinical use of herbs; for example, herbal products included in clinical trials may be of inadequate standards or used in inappropriate doses.31,37 For many botanical products, lack of product characterization, standardization, reproducibility, safety, and basic information on pharmacology remain an obstacle to their use and acceptance by oncologists.31,40 Several research institutions, such as the National Cancer Institute and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, have placed botanical medicine and cancer among of their research priorities, and have acknowledged the importance of including nonconventional practitioners who use botanicals in establishing study designs.

Herbs Used in the Treatment of Breast Cancer

Based on preliminary in vitro research and the efficacy of botanical products in the treatment of a variety of medical conditions, it is reasonable to expect that herbal medicines may offer numerous possibilities as preventative and therapeutic interventions for patients with cancer (Box 10-5).41 An extensive body of literature exists documenting the in vitro and in vivo effects of isolated chemical constituents and single botanical entities. Little research is being done, however, in the actual practice of clinical herbal medicine and even less in herbal medicine and cancer. Many herbal practitioners, mindful of their dubious legal position in the United States, do not treat cancer at all, and others who do tend to fulfill a supportive, adjunctive role rather than becoming the primary care provider.41 As a consequence the records of botanical practitioners are often inaccessible, and lack of a standardized system of record keeping in the profession often leads to inadequate documentation of clinical botanical care. In reviewing the efficacy of herbal medicine in treating breast cancer, there is a dearth of reliable, reproducible evidence.41

BOX 10-5 Commonly Prescribed Herbs

Data from Cabrera C: Treatment of breast cancer with herbal medicine and nutrition, 2004.

Immunostimulation

One of the most commonly cited reasons women with breast cancer give for using herbs is to stimulate or enhance immune function. A number of herbs have immunostimulatory effects. Conventional cancer therapies are known to have adverse effects on immunity and low cell counts can interfere with treatment schedules.37 Therefore, it makes sense that herbal therapies used to boost the immune system might be beneficial to patients undergoing conventional therapies. However, there is concern that these therapies may interfere with the tumor-killing effects of conventional treatments.37 Further, the immune system is incredibly complex and there are numerous immunostimulatory effects that are irrelevant to cancer treatment. For example, immunologic functions related to inflammation and allergic reaction may have little to do with a beneficial cancer response, although stimulating natural killer (NK) cell functioning is an important response. Therefore, it is critically important that research be conducted on the immunologic end points of claims for botanical therapies used tomodify immune function and how these relate to conventional treatment goals and interact with conventional therapies.37 Herbs commonly used as immunostimulants include maitake and other medicinal mushrooms, astragalus, and many adaptogenic herbs, the latter of which are also used to modulate the stress response (see Chapter 7).

Medicinal Mushrooms

Medicinal mushrooms are among the most commonly prescribed anticancer natural products with data from controlled clinical trials suggesting possible benefit in cancer treatment.42 Maitake mushroom (Grifola frondosa) is among those used. Medicinal mushrooms contain a class of polysaccharides known as beta-glucans that promote antitumor immunity related to antibody–Fc interactions by activating complement receptors. Mouse models have demonstrated that beta-glucans act synergistically with therapeutic antibodies such as trastuzumab or rituximab.42

Antioxidants and Green Tea

As many as 25% to 84% of patients with cancer use antioxidant supplements. Both in vitro and in vivo research suggest an antitumor role for antioxidants, including inhibition of tumor cell growth, induction of cellular differentiation, alterations in cellular redoc, and enhanced effects of cytotoxic therapies. Chemotherapeutic agents such as alkylating agents, antimetabolites, and radiation lower antioxidant status, generating free radicals that have cytotoxic effects.43 Cancer patients are often told not to take antioxidant herbs and supplements during the course conventional treatment because of the apprehension that antioxidants will reduce the efficacy of these therapies by eliminating the free radicals. However, adjunctive therapies such as mesna and amifostine, also antioxidants, are commonly given along with other chemotherapeutic agents and do not reduce their efficacy, although antioxidants do appear to reduce the frequency and severity of toxic effects associated with chemotherapy.43 In 2005, antioxidants were the most popular CAM therapy used for treating breast cancer.44

Green tea, prepared from the leaves of Camellia sinensis, has been consumed as a beverage for nearly 50 centuries. Next to water, it is the most widely consumed beverage in the world.45 Multiple lines of evidence, mostly from population-based studies, suggest that green tea consumption is associated with reduced risk of cancer, including breast cancer. 45 46 47 48 Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a major polyphenol found in green tea, is a widely studied chemopreventive agent with potential anticancer activity. Green tea polyphenols inhibit angiogenesis and metastasis, and induce growth arrest and apoptosis through regulation of multiple signaling pathways.45 Apparently, EGCG functions as an antioxidant, preventing oxidative damage in healthy cells, but also as an antiangiogenic agent, preventing tumors from developing a blood supply needed to grow larger. Epidemiologic studies suggest that green tea compounds could protect against cancer, but data are inconsistent, and limitations in study design prevent generalizability of published findings.49 Some limited evidence suggests that green tea may have down regulatory effects on circulating estrogen levels, proposed as possibly beneficial in estrogen-receptor positive breast cancers.50 High consumption of green tea was closely associated with decreased numbers of axillary lymph node metastases among premenopausal Stage I and II breast cancer patients, and with increased expression of progesterone and estrogen receptors among postmenopausal ones.51

It is recommended that women consume at least four to five cups of green tea per day for chemoprotective effects. Tea is much lower in caffeine than coffee, and a healthy alternative. Decaffeinated green tea products provide a comparable level of antioxidants to caffeinated green tea and may be substituted by caffeine-sensitive individuals.52

Phytoestrogens and Breast Cancer

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived nonsteroidal estrogens that are structurally or functionally similar to endogenous estradiol.53 The major classes of phytoestrogens discussed here are the isoflavones (daidzein and genistein) and the lignins (enterodiol and enterolactone). Phytoestrogens are able to bind to the estrogen receptor, and while stimulating it, do so at only a minimal fraction of the strength of endogenous 17β-estradiol. It is believed that this weaker binding actually acts as an antiestrogenic effect in the presence of a high endogenous amount of estrogen, preventing the stronger endogenous estrogen from binding to estrogen receptors.52,54

Soy is the richest dietary source of isoflavones, whereas flax is a major dietary source of lignins. Findings of low rates of breast cancer among Asian women who regularly consume soy products in their diets, and the fact that breast cancer rates begin to approximate those of US women when Asian women consume a Western diet, has stimulated a significant amount of research into the possible protective role of dietary phytoestrogens against breast cancer.54,55 Conversely, trends in increased consumption of phytoestrogens as a dietary supplement as a result of the popularity of phytoestrogens based on these findings has raised serious concerns that their estrogenic effects may actually increase the risk or recurrence of breast cancer; thus, in spite of a great deal of research, the topic of phytoestrogens and breast cancer remains highly controversial.54

Research on the health benefits of soy foods and soy extracts and isolates is contradictory and confusing. Twenty-two case control and cohort studies examined the incidence of breast cancer among women with and without a diet high in phytoestrogens. A meta-analysis of 21 studies found a significantly reduced incidence of breast cancer among past phytoestrogen users. Increased radiologic density has been associated with a four- to sixfold increased risk of breast cancer.56 Three clinical trials have demonstrated an inverse association between dietary phytoestrogen intake breast density, two using similar isoflavones and one reporting on lignins. 57 58 59

None of the available RCTs documents a protective effect of phytoestrogens on the clinical end points of breast cancer.60 Women who were high soy consumers during adolescence demonstrate a 23% risk reduction compared with matched controls, and consuming soy in adult life as well increases the risk reduction to 47%. Phytoestrogens may induce differentiation of breast epithelium during early childhood and puberty, thus making the breast epithelium less sensitive to noxious agents such as chemical carcinogens. Breast epithelia may no longer be sensitive to phytoestrogens after pregnancy.60 Eating little soy in adolescence but more in adult life does not confer any advantage.61 This is clinically significant because it promotes the use of soy as an early preventative but it challenges the usefulness of soy products to treat breast cancer in women who have not grown up eating such foods. The value of soy supplementation postadolescence is of dubious value, and one study actually demonstrated increase breast density in women who consumed large amounts of soy as adults.

Controversy exists as to the clinical significance of all these findings, and there is as yet no consensus of scientific opinion. The variability in outcomes of studies looking at the protective effects of phytoestrogens may result from individual variability in phytoestrogen metabolism and bioavailability and content of isoflavones in supplements. Both isoflavone and lignin metabolism are dependent on gut flora. Individual differences in gut flora, bowel transit time, and genetic polymorphisms comprise variations that may encourage or inhibit the conversion of phytoestrogens into beneficial metabolites. A study by Setchell et al. analyzed 33 different phytoestrogens supplements for isoflavone content and found that there were considerable differences between the amount the manufacture claimed to be in the product and the actual content.62 Dietary fiber content affects the absorption, reabsorption and excretion of estrogens and phytoestrogens. 63 64 65 Additionally as phytoestrogen metabolism is dependent on availability of specific gut flora, antibiotic use may interfere with metabolism of phytoestrogens.54

In summary, the relationship between phytoestrogens and breast cancer appears to be dependent on a number of variables, including age at exposure, individual variability in metabolism, endogenous hormone levels, form in which phytoestrogens are consumed (i.e., as foods or supplements), and whether soy products are fermented, which may increase bioavailability.54,62,66 Adolescent exposure to soy foods appears to be one key to its protective effects against breast cancer.67 Although it cannot be stated without a doubt that there is no increased breast cancer risk from a diet high in phytoestrogen-containing foods, there are no data indicating that prolonged use of a phytoestrogen-rich diet induces malignant growth of hormone-dependent tissue.60 Including phytoestrogens-rich foods such as tofu, tempeh, soy milk, and flax seeds as part of an overall balanced diet is considered likely to be safe, and possibly even health promoting; however, supplemental intake of phytoestrogen products is not advisable, particularly for women with a history of breast cancer or breast cancer risk.54

Reduction of Side Effects of Conventional Therapies and Disease Symptoms

Patients commonly turn to CAM therapies for the reduction of side effects of conventional therapies and disease symptoms.68 Acupuncture relieves nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, postmastectomy massage reduces lymphedema, and mind–body therapies help relieve the stress and pain associated with breast cancer treatment.37,68 A number of herbs may be considered for the reduction of nausea, pain, and anxiety associated with treatment. Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) has been shown to be effective in several trials in reducing nausea associated with chemotherapy and surgery. Its mechanism of action, although not entirely known, appears to be a possible anti–5-HT action, possible reduction of GI motility, and reduction of feedback to central chemoreceptors.52 Although not all trials have demonstrated efficacy, given generally positive findings, a high level of safety, and low side effects profile, it may be considered safe for use in patients experiencing problems nausea and vomiting during cancer treatment. High doses may theoretically inhibit platelet function.52 St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is used to treat mild to moderate depression. Its mechanisms of action include inhibition of the reuptake of 5-HT, DA, NE, and GABA, and L-glutamine in vitro.68 Because of its interaction with CYP 3A4 it has been shown to lower the efficacy of irinotecan and tamoxifen.68 Kava kava (Piper methysticum) or passion flower (Passiflora incarnata) can be considered for patients with anxiety. The former has been associated with hepatotoxicity (see Plant Profiles: Kava kava). The latter is also used for insomnia and neuralgias, and has a very good safety profile, although it may potentiate centrally acting sedative drugs.

Black Cohosh

Women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer experience increased intensity of menopausal symptoms, particularly hot flashes. Black cohosh has commonly been recommended for reduction of this troublesome symptom, and although many women report it effective, research evidence suggests that it is no more effective than placebo for women undergoing chemotherapy-induced menopausal vasomotor symptoms.69 See Plant Profiles: Black Cohosh, for safety considerations.

The Hoxsey Formula and Essiac

The Hoxsey formulas are a combination of an externally applied yellow or red salve, respectively, containing arsenic sulfide, sulfur, and talc or antimony trisulfide, zinc chloride, and bloodroot; and a cathartic, “immune stimulating” liquid “tonic” to be taken internally consisting of a mixture of licorice, red clover, burdock root, stillingia root, barberry, cascara, prickly ash bark, buckthorn bark, and potassium iodide. A similar formula intended for oral use, without the buckthorn bark and with more cascara sagrada and prickly ash, was listed in the 1926 United States National Formulary (5th ed, 1926) and the 1936 sixth edition as an official remedy known as “Compound Fluidextract of Trifolium,” and was first described in 1898 in the King’s American Dispensatory. A 2002 survey of naturopathic physicians in the United States and Canada treating patients with breast cancer reported that the Hoxsey formula was used by 29% of the 161 responders treating localized breast cancer and 24% of the 72 responders treating metastatic breast cancer.70 No toxicity associated with the Hoxsey tonic has been reported, but the potential of toxicity exists from some of its components. No peer-reviewed scientific studies have been published regarding the effectiveness of the treatment.71 The topical applications are potentially caustic and damaging to the breast tissue.

Essiac—typically a combination of burdock root (Arctium lappa), Indian rhubarb (Rheum palmatum), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and the inner bark of slippery elm (Ulmus fulva or U. rubra)—has become one of the more popular herbal remedies for breast cancer treatment, secondary prevention, improving quality of life, and controlling negative side effects of conventional breast cancer treatment.72 The formula may also variably include blessed thistle (Cnicus benedictus), red clover (Tinfolium pratense), kelp (Laminaria digitata), and watercress (Rorippa nasturtium aquaticum).71 In vivo and animal studies have reported antioxidant effects, competitive estrogen receptor binding, immune stimulation, inhibition of cell proliferation including human cancer cells, and laxative and bile-stimulating activities. Results have been inconsistent and have required doses than recommended for general consumption to achieve. A phase II trial in collaboration with the British Columbia Cancer Agency was discontinued apparently because of difficulties in enrolling patients.

A cohort study (n = 510) by Zick et al. to determine the effects of Essiac on health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) between women who are new Essiac users (since breast cancer diagnosis) and those who have never used Essiac, with secondary endpoints of differences in depression, anxiety, fatigue, rate of adverse events, and prevalence of complications or benefits associated with Essiac during standard breast cancer treatment found that Essiac does not appear to improve HR-QOL or mood states and seemed to have a negative effect, with Essiac users doing worse than the non-Essiac users.72 This might be attributed to the fact that the group of users comprised younger women with more advanced stages of breast cancer, and both of these subgroups of patients have been shown to be at a significantly increased risk for negative mood states and/or a decreased sense of well-being. The women were taking low doses (total daily dose 43.6 ± 30.8 mL) of Essiac that corresponded to the label directions found on most Essiac products. Friends were the most common source of information, and most women were taking Essiac to boost their immune systems or increase their chances of survival. Only two women reported minor adverse events, whereas numerous women reported beneficial effects of Essiac.72

In another study, researchers evaluated the effects of Essiac and another popular herbal product, Flor-Essence, on a line of human breast cancer cells. Exposure to the tonics produced a dose-dependent increase in ER activity but did not affect cell proliferation. The authors concluded that Flor-Essence and Essiac Herbal Tonics can stimulate the growth of human breast cancer cells through ER-mediated as well as ER-independent mechanisms of action.73 According to Low Dog, there is no compelling evidence that these products reduce tumor size, prolong survival, or improve quality of life.

AFTER BREAST CANCER…

Only recently have the emotional, social, and even medical complexities of life after breast cancer begun to be recognized. Even the terminology remains uncertain—do women think of themselves as breast cancer survivors? Do they move on or spend their lives worrying about recurrence? Are there preventative strategies they can use to reduce their risk of recurrence? Currently there are probably more questions than answers. From a medical standpoint, the following follow-up guidelines are recommended:3