10 Breast cancer

Aetiology

The reported risk factors include hormonal, genetic, dietetic and radiation. Table 10.1 shows these risk factors and protective factors for breast cancer. The effect of hormones, notably oestrogen, is the most significant aetiological factor in breast cancer. Genetic factors in breast cancers are dealt with in Chapter 5 (p. 47). BRCA1 mutation associated cancers tend to occur at an early age, are highly aggressive and are typically negative for oestrogen (ER), progesterone (PgR) and human epithelial growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu (’Triple negative’). BRCA2 mutations account for 1% of breast cancers which are often ER and PgR positive.

| Relative risk | |

|---|---|

| Early menarche (before 11 years) | 3 |

| Late menopause (after 54 years) | 2 |

| First pregnancy after 40 years | 3 |

| Nulliparity | 3 |

| HRT | 1.7 |

| Oral contraceptive | 1.2 |

| One maternal first degree relative | 1.5–2 |

| Two first degree relatives | 3–5 |

| First degree relative diagnosed before 40 years | 3 |

| Bilateral breast cancer | 4 |

| Alcohol | 1.3 |

| Protective factors | |

| Artificial menopause before 35 years | 0.5 |

| Increased parity | 0.5–0.8 |

| Age at first pregnancy less than 30 years | 0.6–0.8 |

| Breast feeding | 0.8 |

Pathogenesis and pathology

Breast cancer arises from the epithelial cells lining the terminal duct lobular unit. Development of invasive breast cancer is thought to be due to a multi-step process. WHO classification of breast cancer is shown in Box 10.1.

Malignant breast lesions

The postoperative pathology report should include: number of tumours, maximum diameter of largest tumour, histologic type and grade, circumferential excision margin and minimal margin, vascular invasion, number of nodes retrieved, number of nodes involved and extent of involvement (e.g. micrometastasis or metastasis), presence of DCIS and immunohistochemical status of ER and PgR and HER2. Patients with an ambiguous HER2 (2+) status on immunohistochemistry, require fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to look for gene amplification (Box 10.2).

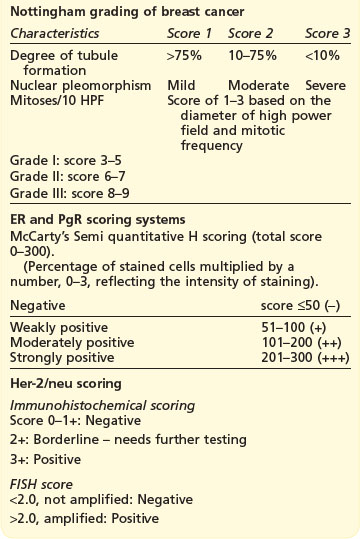

Box 10.2

Grading and scoring systems in breast cancer

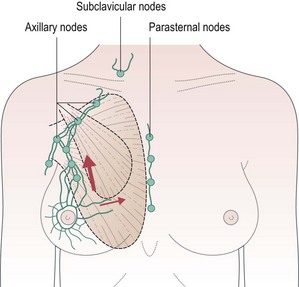

Surgical anatomy of breast and lymphatics (Figure 10.1)

The adult breast extends from the second rib superiorly to the sixth rib inferiorly and from the lateral edge of the body of the sternum medially to mid-axillary line laterally. There are approximately 20–30 axillary lymph nodes which are surgically defined as:

More than 75% of all lymphatic drainage passes through the axillary nodes and the remainder through the internal mammary nodes. There is a higher risk of internal mammary node involvement with medially located tumours and in those with extensive axillary nodes. Apical axillary node involvement leads to blockage of lymphatics and subsequent retrograde spread of cancer to supraclavicular nodes (see Figure 10.1).

Presentation

Example Box 10.1

Breast cancer: key points for a case presentation

All patients

Patient with local relapse

Many patients with early breast cancer are detected during screening by mammography.

Initial assessment

‘Triple’ assessment of patients with suspected breast cancer includes a combination of clinical examination, breast imaging (mammography and/or ultrasound) and pathologic evaluation (core biopsy). With this approach, a definite diagnosis of breast cancer can be made in 99% of cases.

Breast imaging

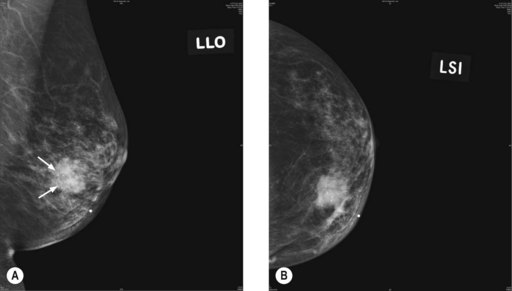

Mammogram

The commonest mammographic abnormality of DCIS is micro-calcification (in 50% cases). Other features include asymmetric density and mass. High-grade DCIS is associated with linear and branching calcification, whereas low-grade DCIS is associated with fine and granular calcification. Invasive cancer appears as a speculated mass (Figure 10.2). Although calcification can occur in various conditions, a linear small (<1 mm in diameter), non-uniform size and clustered calcification is suggestive of malignancy.

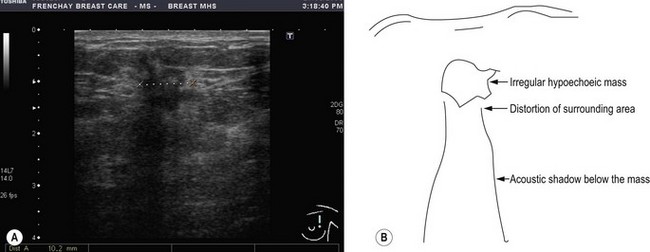

Ultrasound

Ultrasound examination of the breast helps to distinguish between solid and cystic lesions of more than 1 cm in size. Malignancy appears as a hypoechoic lesion with associated distortion of the surrounding tissues and an acoustic shadow on the breast tissue below it (Figure 10.3). It is also useful to assess axillary nodal status as well as to aid in guided FNA and core biopsy. Ultrasound is less sensitive than mammography for early detection and hence is not used for screening.

MRI scan

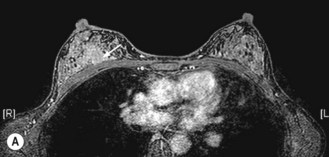

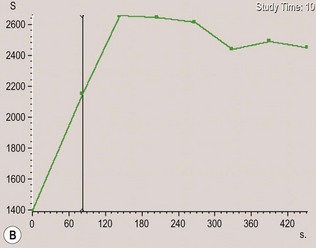

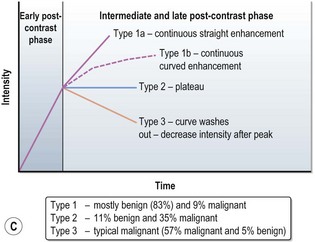

MRI can more accurately define the size of the tumour compared with mammography and is better in delineating intraductal disease and multifocal disease. MRI has a high sensitivity in detecting cancers (almost 100%) and lower sensitivity in detecting DCIS (80%), but has a higher false positivity. MRI is more useful for young women who have dense breast tissue (Figure 10.4). MRI is particularly useful in screening women less than 40 years with a high risk of breast cancer, to rule out multifocal disease prior to conservation, imaging women with implants and to distinguish scars from tumour recurrence.

Staging

Management of carcinoma-in-situ

Ductal carcinoma-in-situ (DCIS)

With mammographic follow-up, breast cancer disease free survival in DCIS approaches 100%.

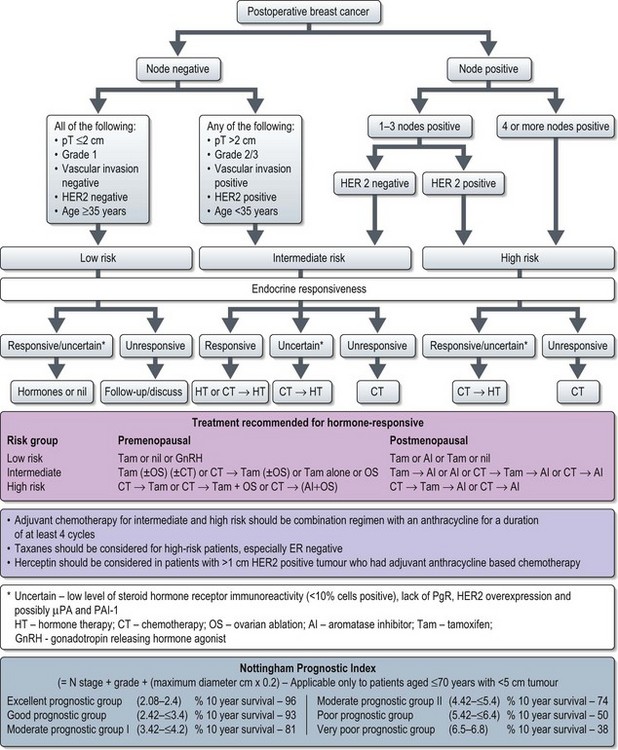

Management of early stage invasive cancer (Figure 10.5)

Figure 10.5 Adjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer (based on St. Galen International consensus 2007).

Surgery

Surgery is aimed at removal of the primary breast tumour and staging and/or treating the axilla. Primary breast surgery can be either conservative (wide local excision – WLE followed by radiotherapy) or mastectomy. Conservative surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy offers a better cosmetic outcome than mastectomy. However, not all patients are suitable for breast conservation (Box 10.4).

Box 10.4

Contraindications to breast conservation surgery

Breast surgery

Breast reconstruction after mastectomy

Methods of reconstruction include:

Adjuvant radiotherapy (Boxes 10.5 and 10.6)

Box 10.5

Radiotherapy in breast cancer

Postmastectomy radiotherapy (Boxes 10.5 and 10.6)

Patients with ≥4 involved nodes after axillary dissection are at risk of supraclavicular recurrence (>15%) and hence supraclavicular radiotherapy is advised. Axillary radiotherapy is not recommended after axillary dissection as there is 30–40% risk of significant lymphoedema and the risk of isolated axillary recurrence without radiotherapy is only 1–4%. However, it may be considered in rare instances of residual macroscopic disease in the axilla or positive dissection margin.

Adjuvant systemic treatment

Hormone receptor status and HER2 status are the most important determinants in the choice of systemic treatment. Patients with ER+ tumours may receive hormones alone or a combination of endocrine treatment and chemotherapy. Patients with ER− tumours are considered for adjuvant chemotherapy alone. However, there are no clear guidelines on the threshold of benefit above which adjuvant chemotherapy is advised. Some experts justify adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with <90% 10-year survival and others use an absolute survival benefit of at least 3–5% at 10 years with chemotherapy. Several decision making tools (e.g. adjuvant online – https://www.adjuvantonline.com and Nottingham prognostic index) have been developed to help to make adjuvant treatment decisions. According to the 2007 St. Gallen Consensus adjuvant chemotherapy is generally recommended for intermediate and high-risk patients (Figure 10.5). Patients with HER2+ tumours of >1 cm and/or nodal involvement are considered for adjuvant trastuzumab (see later, p. 128).

Adjuvant chemotherapy

A practical approach is to use anthracycline based chemotherapy (e.g. FEC or Epi-CMF) for patients without high-risk early breast cancer and taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for high risk patients needing chemotherapy (Figure 10.5). In the UK, anthracyclines-taxane combination is licensed to use in patients with node positive breast cancer. Box 10.7 shows the commonly used chemotherapy regimes in breast cancer

Box 10.7

Chemotherapy regimes in breast cancer

Adjuvant/neoadjuvant

Palliative

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (Figure 10.5)

The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Group overview of adjuvant tamoxifen has shown that tamoxifen for 5 years results in a 41% proportional reduction in recurrence and 34% proportional reduction in mortality in oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer patients irrespective of age, menopausal status, and administration of chemotherapy. There is also a proportional reduction of contralateral breast cancer by 47%.

In postmenopausal women the adjuvant hormone options are:

Hormonal agents

The usual side effects of AIs are hot flushes, joint pain and muscular stiffness. The long-term risk of osteoporosis is a concern (see p. 61, late effects). All patients need bone mineral density assessment by DEXA scan prior to starting AI. Patients with osteopenia need vitamin D and calcium supplement whereas those with a T-score less than −2.5 SD (osteoporosis) need bisphosphonates. All patients on AI need a 2-yearly DEXA scan.

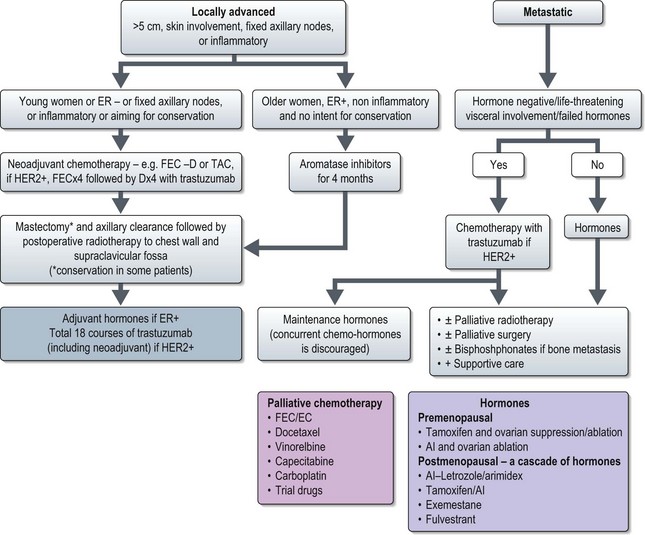

Locally advanced disease (T3 N1, T1–3 N2–3, T4 N0–3) (Figure 10.6)

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the standard treatment for patients with large primary tumours aiming for conservation and for inflammatory breast cancer (see p. 132). Chemotherapy results in a 70–90% response with a 20% pathological complete response. NSABP B-27 showed that an initial anthracycline regime followed by docetaxel results in a better response rate (90.7% vs. 85.5%, p < 0.001) and pathological complete response (64% vs. 40%, p < 0.001). In patients with HER2 positive tumours addition of trastuzumab results in improved pathological response (65% vs. 26%, p = 0.016) and it is advisable to incorporate trastuzumab with the neoadjuvant non-anthracycline chemotherapy. One such approach is to give initial 3–4 courses of anthracycline chemotherapy followed by taxanes with trastuzumab. In breast cancer, type and degree of response to primary systemic treatment predicts disease-free as well as overall survival.

All patients need postoperative radiotherapy to chest wall or breast (Figure 10.6). Adjuvant systemic treatment depends on hormone receptor and HER2 status.

Metastatic disease (any T, any N, M1) (Figure 10.6)

Patients with hormone receptor positive disease without life-threatening visceral involvement are treated with hormonal treatment. In premenopausal women who have not previously had tamoxifen or discontinued for >12 months, the standard option is tamoxifen and ovarian ablation or suppression. Otherwise, an AI with ovarian ablation may be considered.

Chemotherapy is used in patients with receptor negative tumours, hormone resistant tumours, and life-threatening progressive disease. Chemotherapy results in a 50% response rate usually lasting less than one year. Based on meta-analysis, anthracyclines result in a greater clinical benefit than a CMF regime and should be considered as first-line treatment if the patient has not previously received an anthracycline. Taxanes are the options after anthracycline failure. Both docetaxel and paclitaxel have proven activity. Other agents used in breast cancer include capecitabine, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, carboplatin, etc. (Box 10.6).

A very small subset of patients present with bone marrow failure subsequent to extensive bone disease. Modified chemotherapy with low-dose weekly anthracycline or taxanes is the option in these patients (Box 10.6).

Palliative care

Prognostic factors and outcome

Long-term prognosis can be estimated using the Nottingham prognostic index (Figure 10.5) or using online programmes such as adjuvant online (www.adjuvantonline.com).

5-year survival of stage I breast cancer is 85%, stage II 70%, stage III 50% and stage IV 20%.

Screening and prevention

Assessment and prevention of breast cancer in women with family history of breast cancer is given on p. 47.

Special situations

Inflammatory breast cancer

25% of patients present with metastatic disease when the aim is palliative and the treatment principle is the same as metastatic breast cancer.

Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, Orecchia R, Viale G. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:1727-1741.

Benson JR, Jatoi I, Keisch M, et al. Early breast cancer. Lancet. 2009;373:1463-1479.

Buchholz TA. Radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:63-70.

Pagani O, Senkus E, Wood W, et al. International guidelines for management of metastatic breast cancer: can metastatic breast cancer be cured? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:456-463.

Roy V, Perez EA. Beyond trastuzumab: small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in HER-2-positive breast cancer. Oncologist. 2009;14:1061-1069.

Bosch A, Eroles P, Zaragoza R, Viña JR, Lluch A. Triple-negative breast cancer: molecular features, pathogenesis, treatment and current lines of research. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:206-215.

Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet. 2006;367:595-604.

Dawood S, Ueno NT, Cristofanilli M. The medical treatment of inflammatory breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:64-71.