Chapter 16 Breast Augmentation

summary

To achieve successful breast augmentation results, it is crucial to:

Introduction

The female breast is a universal symbol of sexuality, motherhood and femininity today, dating back even to the time of ancient cave paintings. In the 1940s Alfred Kinsey observed that the female breast could inspire more sexual arousal in men than the sex organ.1 Since its introduction in 1962, modern breast augmentation with implants has become one of the most common aesthetic procedures, receiving more media attention than any other. However, much reporting, especially in the non-professional literature, has been faulty. More than one million breast implants are now inserted every year, 250 000 in the US. Most patients are very satisfied with the results.2 Most experience better psychological functioning and body image; many experience less anxiety and depression3 and even have better sexual relations with their partners. However, most women do not seriously contemplate the possibility of unfavourable results.4 Various complications are possible and should be seriously considered before undergoing a procedure. The risk should be minimized by a meticulous preoperative evaluation and surgical procedure. Selecting the ideal dimensions for implants, based on biological prerequisites, is crucial.

Contraindications

The main contraindications are psychological. Patients must have realistic expectations of the procedure and understand benefits and risks. Those who do not understand, or are psychiatrically unstable and have unrealistic expectations are contraindicated. Clearly, a medical history and physical examination have to be undertaken to rule out health problems that may be contraindications. Older patients and patients with a genetic disposition for breast cancer should undergo a preoperative mammogram. General medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus and heavy smoking are only relative contraindications. Radiation therapy is a relative contraindication as it significantly increases the rate of capsular contraction.

Patient and Implant Selection

Patient communication

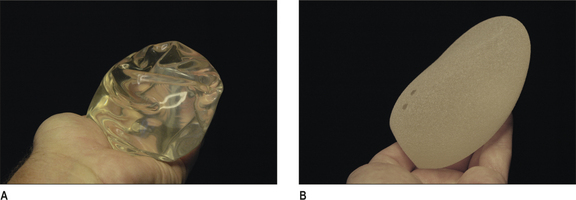

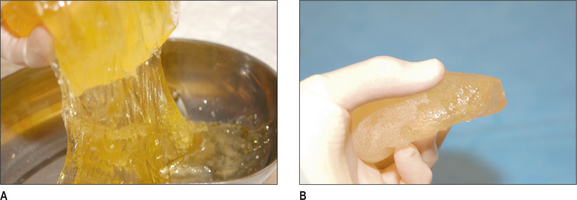

Previously, decision-making has been relatively arbitrary and based mainly on the surgeon’s experience without detailed measurements and analysis. In the last decade this has changed dramatically. Today, breast augmentation is no longer a ‘volumetric’ procedure, but a dimensional planning process. With the introduction of form-stable, high-cohesive silicone gel implants, dimensional planning has become crucial (Fig.16.1B). A low cohesive or liquid implant filler (Fig. 16.1A) can be deformed and made to fit in a poorly planned implant pocket, but with form-stable devices this is no longer the case.

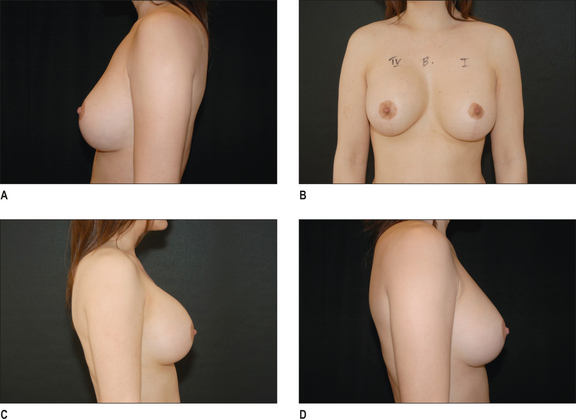

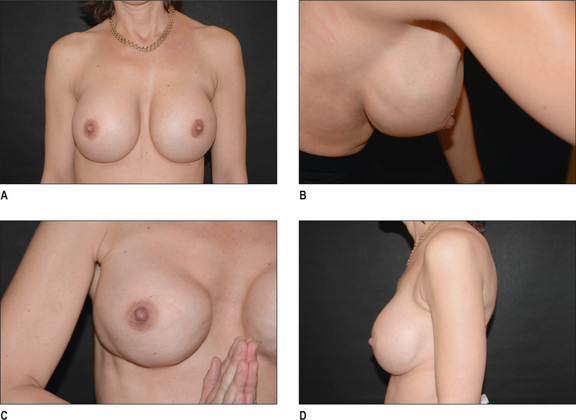

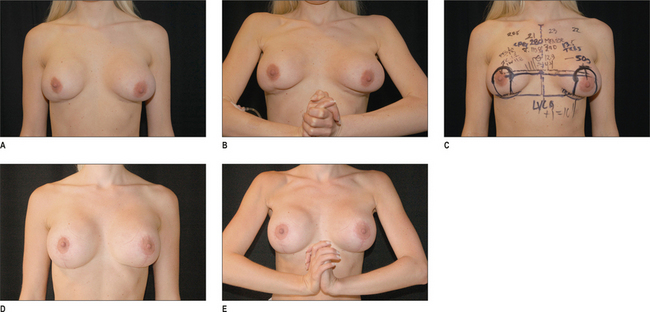

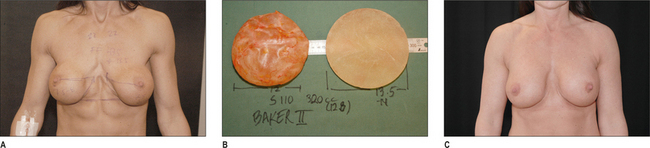

The first step in implant selection is the understanding of the patients’ expectations and desires. They must be told what the tissue limitations are and the drawbacks in selecting large implants should be clearly explained. During patient consultation, a full size mirror is useful to show the patient present and expected breast dimensions. Displacing the breast medial and lateral can easily demonstrate width limitations and the projection can be demonstrated with a calliper and by cupping the hand at the expected projection of the new breast. To use sizers in a tight-fitting sports bra may give the patient a certain feeling for the expected volume, but unless the patient is completely flat, this is of limited use in describing dimensions. The patient must understand that a condition for achieving the demonstrated breast dimensions is that no capsular contraction occurs in the postoperative phase (Fig. 16.2A-D). A severe capsular contraction could alter dimensions considerably, especially if low cohesive fillers are used (Fig. 16.3A-C & Fig. 16.4A & B).

Fig. 16.3 A, After subglandular implantation in thin patients breasts have an unnatural appearance compared to sub-muscular implantation. B, Illustrates the implant with capsule on the left side and without on the right side. Only limited degree of capsular activity is noted in spite of the unnatural appearance in Figure 16.3A. C, After exchanging to implants in a new submuscular pocket.

Selection of implant filler, shape and surface

Only silicone gel and saline have been used long term and can be regarded as safe and proven. All implants consist of a solid silicone envelope. The surface may be textured or smooth. In the sub-glandular position, textured implants are favoured, whereas with sub-muscular placement, implants can be either smooth or textured (Fig. 16.1A & B). The benefit of silicone as a filling material is its softer, more ‘natural’ consistency and form (Fig. 16.5A-D). Saline implants have a higher rupture-risk, especially if these are not overfilled. However, the latter increases breast firmness. Silicone gel is available in a form-stable version; the round implant will retain its shape in standing position, as opposed to saline or standard responsive silicone gel implants, which become more position dependent. An anatomical high cohesive form-stable silicone implant will also maintain its anatomical shape in all positions. Form-stable silicone implants have a very low incidence of rupture.5

Selections of implant dimensions

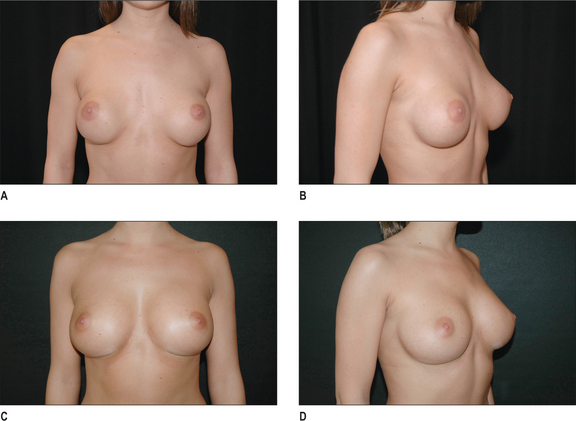

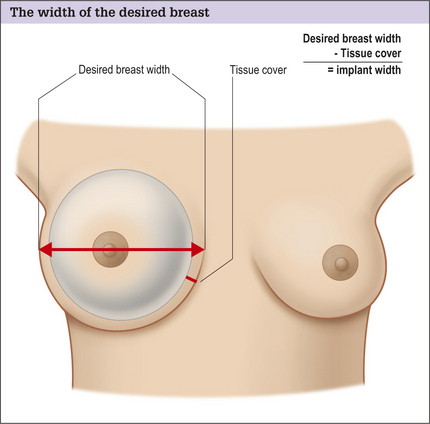

Regardless of implant type, a dimensional analysis should be undertaken. If high cohesive form-stable devices are used this is crucial, as these implants cannot be deformed. The most important dimension to define is the ideal implant-base width, which should be measured with a calliper. Existing glandular tissue width should also be measured. If an implant with a base width exceeding the existing breast width is selected, the risk of implant edge palpability and visibility is increased (Fig. 16.6A-D). However, with a very narrow breast base width, like that in tuberous and contracted breasts, the existing width must be exceeded for a natural appearance. The new desired inter-mammary distance is usually about 2-3 cm and laterally the anterior axillary line should be respected. Measuring the ideal width of the desired new breast provides information on ideal implant width if the tissue-cover is subtracted (Fig. 16.7). The covering tissue should be measured with a pinch-test at the expected inner border and at the lateral border of the new breast. These measurements should then be added together and divided by two, as a pinch is a double-fold of tissue. Subtracting the tissue cover from the ideal breast width provides the ideal implant width. From the implant manufacturers’ charts the implant dimensions are found and the upper border of the implant can also be calculated. This is done by elevating the arms 45 ° above the horizontal plane, simulating the expected, ideal nipple position after a correctly performed augmentation (Fig. 16.8A-D). This maneuver can be used to estimate where the upper border of the new implant will be, as half should be located above the nipple areola complex. This can be a useful guide in selecting the ideal implant shape and estimating the upper pole appearance of the augmented breast. When selecting implant projection, this is highly related to the tissue characteristics and to the patient’s desires. The selected projection together with the base dimensions of the implant supplies the implant volume. Implants are thus selected as a result of the dimensions of the ideal new breast and implant.

Preoperative history and psychological considerations

Patients who are unsuitable for surgery must be identified preoperatively. Andersson has proposed a number of questions that, if answered positively, should result in a further appointment before surgery as outlined in Table 16.1.6 During the evaluation, it must be stressed that breast augmentation complexity varies greatly. Tuberous breasts, severe ptosis, secondary augmentation cases and pronounced asymmetries are more difficult to correct.

Table 16.1 List of questions that, if answered affirmatively, warrants additional patient assessment

|

Does the patient have unreasonable expectations, make frequent demands of surgeon and/or staff and displace a sense of urgency?

|

Operative Technique

Relevant surgical anatomy

The appearance of the female breast is greatly affected by various factors, particularly heredity. Glandular tissue is covered with a fat layer above the Scarp’s fascia and the amount of fat interspersed in the glandular tissue varies greatly. This part of the breast is relatively unimportant from an anatomical standpoint when it comes to performing breast augmentation surgery, as implants are always placed under the glandular tissue. The most important structure germane to breast augmentation is the pectoralis major muscle. This is a strong, predominant fleshy muscle, tendinous only at its insertion into the crista tubercule of the humerus. The pectoralis major has a fairly thin fascia, stronger and more distinct in the upper pole of the muscle. This is relevant to a sub-fascial breast augmentation. The pectoralis major muscle origins in three distinct parts, first along the sternal half of the clavicle, second on the ventral surface of the sternum and costal cartilage numbers II-VI, and thirdly with a slip on the aponeurosis of the external oblique abdominal muscles. It is of importance to note that the width and length of the muscle has a great interindividual variation. The innervations come from the brachial plexus in the axilla. The muscle is a powerful adductor, which flexes, adducts and rotates the arm medially. The pectoralis minor muscle originates from ribs II-V, near the cartilage-bone junction, so the muscle is more lateral in its origin than the pectoralis major. This is important when performing a sub-muscular breast augmentation where the dissection plane should be between the pectoralis major and minor, making it easiest to dissect from medial to lateral between them. The innervations to the breast come from thoracic segments III-VI. Sensory reduction in the breast after augmentation is a common initial complaint. Most patients do not suffer from this after the initial 6 months of healing, but they should be informed of the possibility of chronic sensory reduction, most commonly related to the lateral intercostal branches coming from the upper lateral quadrant. To minimize risk, large implants should not be selected and the sharp dissection in the direction of the axilla should be minimized. This is the only part of the dissection that should be blunt.

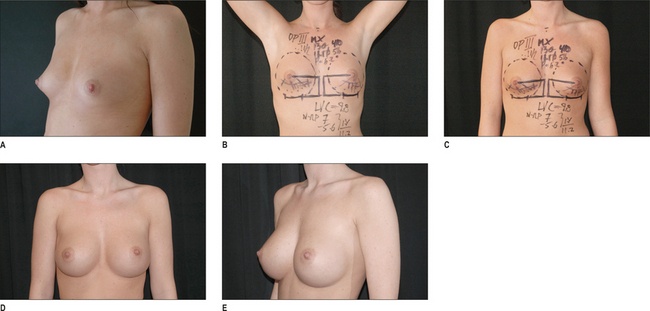

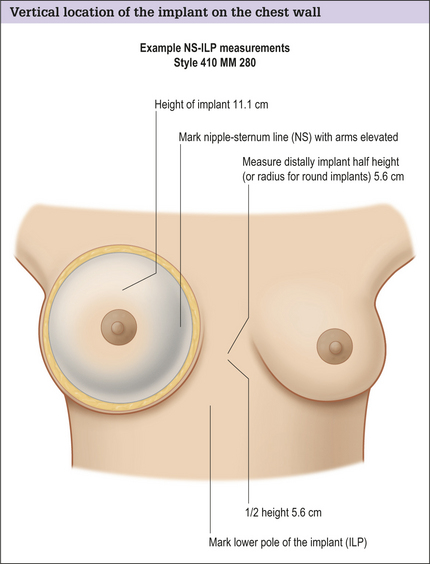

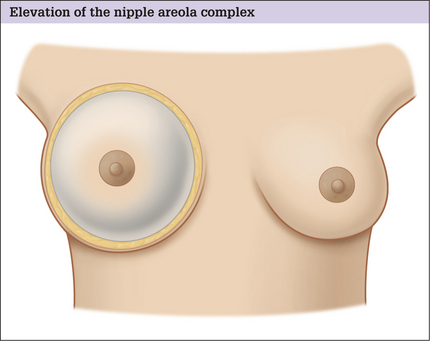

Preoperative markings

Accurate and detailed preoperative marking is essential. Two important questions should be addressed. The first is the vertical location of the implant on the chest wall. If implants are too high the nipple areola complex will point downwards and the upper pole will be too full. If implants are placed too low the breast will be too full in the lower pole. Ideal nipple projection is centrally on the implant, thus the base dimension of the implant is important. Usually, half should be located above the nipple areola complex in the augmented breast and half below it. The ideal postoperative position of the nipple areola complex can be simulated with the arms elevated 45 ° above the horizontal plane; in this position, a line from the nipple to the sternum can be drawn (NS-line) (Figs 16.8A-E & 16.9). As the tissues in the midlines are relatively fixed, measurements of ideal implant height are better done along the sternum. With arms lowered, half of the implant height, or for round implants half the diameter of the implant, is measured distally, and at the distal point a horizontal line is drawn laterally, representing the implants’ lower pole (ILP-line; Fig. 16.10). In patients with asymmetric nipple heights, this will result in different heights of the ILP-line, but the implant will be adequately positioned in relation to the nipple areola complex.

Fig. 16.9 A correctly performed breast augmentation creates an elevation of the nipple areola complex.

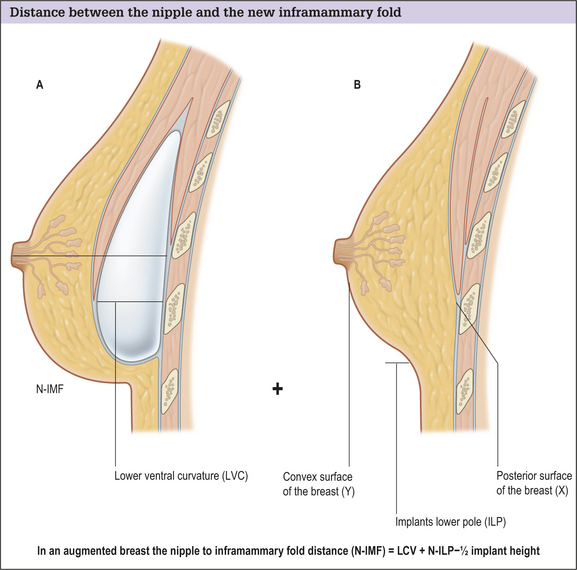

Secondly, the ideal amount of skin in the lower pole of the augmented breast should be calculated; how long should the nipple-infra mammary fold distance be and, if a sub-mammary fold incision should be utilized, where should this incision be placed? Unfortunately, it is seldom recognized that the amount of skin in the lower pole of the breast is greatly affected by the three factors: the width and projection of the implant; the amount of glandular tissue and the characteristics of the envelope. Higher projecting implants with larger base circumference necessitate longer nipple inframammary fold distance. The ideal nipple to inframammary fold distance in the augmented breast is equal to the distance between the ideal nipple projection point on the ventral surface of the implant measured down to the implant’s lower pole (LVC), plus the added distance for the amount of glandular tissue that the patient has preoperatively (Fig. 16.11A & B). The ideal amount of skin between the nipple and the new inframammary fold is calculated by adding the implant’s lower ventral curvature (LVC) and the distance between the nipple and the ILP-line with arms elevated 45 ° above the horizontal plane. Subtracted from this addition is half the implant height. The implant’s lower ventral curvature is today only available from some manufacturers, but can also easily be calculated with a tape ruler measuring the curvature between a vertical (implants projection) and horizontal axis (implants half baseplate of height for anatomical ones) marked on a piece of paper. Added to this the second number is obtained by elevating the arms 45 °, measuring between the nipple and the previously marked ILP-line, and simultaneously compressing the glandular tissue to simulate the effect of the implant on the glandular tissue. Adding this N-ILP-measurement with the LVC (lower ventral curvature) of the implant, and subtracting half implant height provides the ideal distance between the nipple and the inframammary fold. When marking this distance on the breast tissues should be stretched maximally, simulating a tissue stretch and considering envelope characteristics. The final step is to mark the location of the upper pole of the implant and measure tissue covered here. A pinch-test is done and if the pinch is below 2-3 cm (equal to a tissue cover of 1-1.5 cm) muscle cover in the upper pole of the implant is recommended (Fig. 16.8A-E). These markings and measurements7 (the Akademikliniken or AK method) by the author is a more detailed preoperative planning than traditionally used in breast augmentations. This has been developed for form stable anatomical implants but the basic principles of this method is equally applicable for smooth, non form stable and round implants.

Sub-muscular versus sub-glandular implant placement

Indications for both sub-muscular and sub-glandular implant positions exist and the decision should mainly be based on the tissue cover. With the preoperative marking described above, it is easy to measure where the upper implant pole will be located. A pinch and measurement of the tissue with a calliper provides information for implant positioning. If the pinch is below 2-3 cm, this is equal to a tissue cover of 1-1.5 cm and a sub-muscular placement is recommended. With a pinch thickness of more than 4 cm, sub-glandular placement may produce favourable results as such breasts usually are large and a sub-glandular position of the implant may provide more natural aging with gradual ptotis of the breast. Benefits of sub-muscular implant position are that the implant edges are better covered, resulting in less implant edge visibility. It is also less likely that the tissues will become atrophied due to the pressure of the implant. It appears that sub-muscular placement has better long-term aging compared to sub-glandular implants, especially in smaller breasts. Advantages of sub-glandular placements are that the breasts will have no movement during pectoralis muscle activity and a more natural appearance is produced in the ptotic breast. In the tuberous, contracted breast the risk for double bubble deformity in the lower pole is minimized. Sub-glandular implantation is less painful during the initial hours after surgery. The drawbacks of sub-glandular implant positioning can be minimized if the thin pectoralis major fascia is included in the elevated gland. Subfacial implantation is commonly favoured above sub-glandular.8

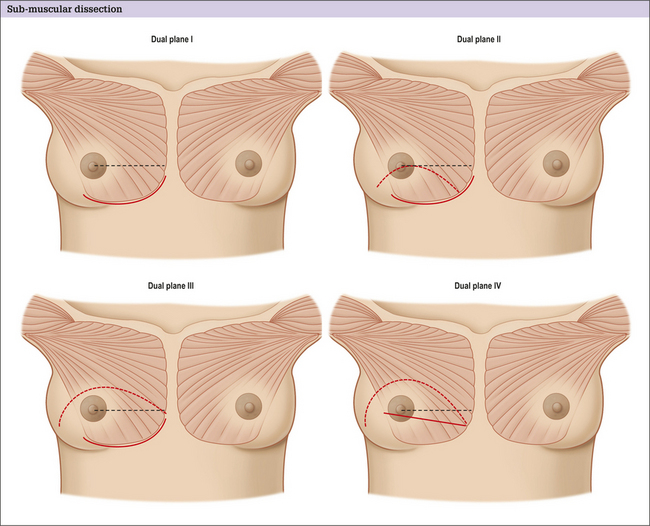

With the modifications of sub-muscular implant techniques, this implant position is more common than sub-glandular/sub-facial. By placing the implant in dual plane position (Fig. 16.12A-D), where only the upper pole of the implant is covered with the muscle, the drawbacks of sub-glandular implantation, such as animation during pectoralis muscle activity, can be minimized.9,10

Incisional approach

The length of the incision depends on the type and size of implant used. Saline filled ones can be inserted through a 3-4 cm incision, whereas form-stable silicone implants necessitate a 4.5-6 cm incision. Four different approaches have been described. Sub-mammary fold incision was first used in the 1970s, this was followed by a periareolar and transareolar incision.11 In the 1970s transaxillary implantation was also popularized.12 This was followed by the description of transumbilical approach for implant insertion.13 Saline implants must be used through the transumbilical route and smooth implants are easier to implant through the axilla. According to the preoperative markings described above, the sub-mammary fold incision has been modified and this ‘new’ sub-mammary fold incision has several advantages.

The new sub-mammary fold incision

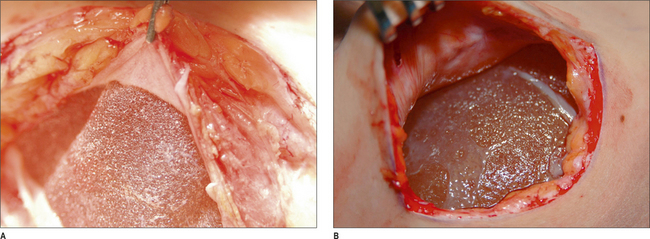

By the exact calculation of the ideal distance between the nipple and the new inframammary fold, the ideal position of the sub-mammary fold incision can be calculated (see markings above). A major reason for the previously bad reputation of the sub-mammary fold incision was that resulting scars were not exactly calculated and not placed in the new position of the sub-mammary fold. Arbitrary location of the incision results in worse sub-mammary scarring. The sub-mammary fold incision offers several advantages: less risk for sensory disturbances that may be pronounced in the periareolar and the axillary approach; less contamination of the implant through the sub-mammary fold incisions; and easy inspection and palpation of the implant pocket. The latter is very important if form-stable devices are used, where it is crucial to position the implant correctly and to avoid buckling and irregularities of the implant edges. It is easy to control the exact position of the implant through the sub-mammary fold. Dual plane dissection and the division of the pectoralis origin of the pectoralis muscle is also easier to divide than through the axillary and the periareolar incision (Fig. 16.13A & B), giving superior control of the sub-mammary fold, especially if the scarpas fascia is fixed to the thoracic wall when creating the new fold (Fig. 16.14A-C).

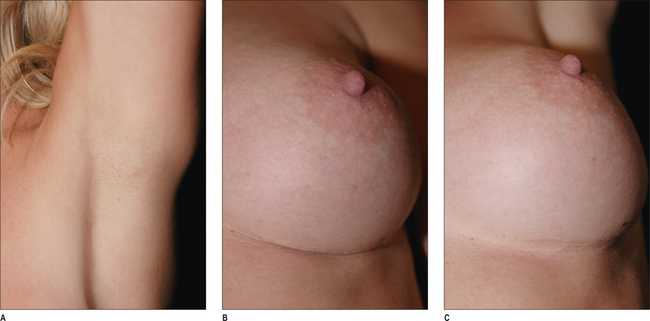

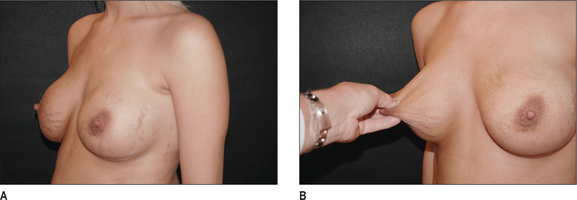

Fig. 16.13 A, Oblique view after submuscular implantation via axillary incision. B, During pectoralis muscle contraction irregularity in the lower pole is seen due to inadequate muscle release, which is much more common via the axillary approach than via the submammary fold, where more control of the muscle division is possible. All the different muscle divisions described in Figure 16.13 are not possible to perform via the axilla.

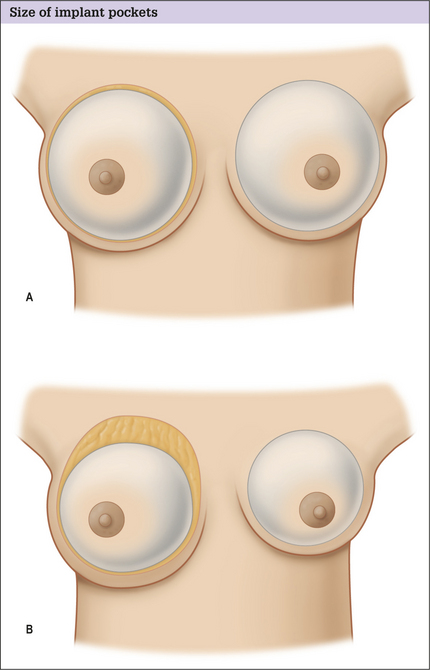

The incision is made with a scalpel and dissection is carried on with cutting cautery (Colorado® Tungsten tip and the Valley lab Force FX® cautery in spray and blend mode facilitates a bloodless dissection). The dissection is vertical, exposing the thoracic fascia. Dissection proximal along this fascia creates a lower sub-glandular pocket. In sub-muscular positioning the pectoralis major muscle’s lower origin is exposed and in dual plane I technique the muscle is elevated together with the gland. More commonly used is the dual plane II, where the sub-glandular pocket is created up to the areola plane. The muscle is then divided distally from its lateral border, cutting it horizontally towards the sternum. The muscle is elevated with a cutting cautery. The muscle is divided obliquely, parallel to the chest wall, to minimize the risk of entering between the ribs and intercostal muscles. When entering the sub-muscular plane, the loose connecting tissue on top of the ribs is exposed and this tissue should be left intact on the ribs, minimizing seroma formation and pain, and facilitating postoperative mobilization. The whole dissection is carried out with a cutting cautery. Blunt dissection should be avoided as this increases trauma, pain and seroma. The dissection is first done in the proximal and medial part of the pocket, and from this medial dissection the lateral extent of the pocket is made, minimizing the risk of entering under-neath the pectoralis minor muscle. The only part of the implant pocket that could be blunt is in the direction of the axilla, minimizing trauma to the sensory innervations of the nipple areola complex. The size of the pocket depends on implant type; form-stable textured implants should have an implant pocket that fits snugly, approximately 0.5 cm wider on each side than the implant base width and 1-2 cm in the proximal direction. Smooth implants move more freely in the implant pocket and the implant pocket can be bigger. The medial inferior origin of the pectoralis muscle is released, curved in a proximal direction to the level of the nipple areola complex.

In dual plane III dissection, the sub-glandular pocket is more extensive, passing the level of the nipple areola complex followed by similar muscle dissection as described for dual plane II dissection, above. In dual plane IV dissection,7 the extent of the sub-glandular part of the pocket is similar to the dissection in dual plane III, but the muscle is divided from the lateral border at the level of the nipple areola complex, more parallel to the fibres (Fig. 16.12A-D). It is important not to divide the medial origin of the pectoralis muscle higher than the NS-line. Muscle division, inferior-medially, should stay 1-2 cm below the NS-line (see markings above). In sub-glandular dissection, elevation of the pectoralis major fascia, together with the elevated breast, minimizes implant edge palpability and visibility in the upper pole.

Axillary approach

The incision in the axilla should be planned at the vertex or possibly 1 or 2 cm medial to it. The incision is made along the skin creases, perpendicular to the length of the axilla. The axillary approach can be used for sub-glandular placement or sub-muscular positioning. No scar is present on the breast; usually it is well hidden and fairly inconspicuous in the axilla. Disadvantages include that the dissection is blind during the most important part and the view of the inferiormedial muscle division is more technically demanding. Use of an endoscope facilitates the muscle division, but the detailed different. Dual plane dissection, as described above, is not possible. It is also difficult to control implant folds and rotations, if form-stable devices are used. Implants are more contaminated through the sweat glands in the axilla and sensory nerve (the lateral thoracic) or sentinel node affection is possible. The surgeon does not have the same control of the shape of the lower pole of the breast as in sub-mammary fold approaches (Figs 16.13A & B & 16.14A-C).

Incision closure

The pectoralis fascia is usually closed with an absorbable suture in the axillary approach, followed by sub-cuticular stitching. In the periareolar approach the dissected gland is usually left open, but can be closed with an absorbable stitch. The new sub-mammary fold incision can be utilized to mark the new sub-mammary fold, resulting in a less conspicuous scar and a better shaped lower pole (Figs 16.14B & C & 16.15). A good grip in the thoracic fascia is taken along the ILP line with an absorbable suture (Monocryl or Monocyn 3/0), passed through the tissues on top of the Scarpas fascia below and above the incision. Usually, three stitches are inserted, one in the midline left untied, while the two lateral ones are tightened. This is followed by a deep dermal ridge suturing with good strong bites of the dermis far away from the wound edge and deeper at the immediate wound edge. This creates a ridging effect and a more relaxed incision line, creating more inconspicuous scars. A sub-cuticular suture is then inserted. Absorbable monofilament sutures are favoured in all layers.

Optimizing outcomes

Complications and Side Effects

Oversized breast augmentation adds to the frequency of complications14,15 (Fig. 16.6A-D). One has to avoid operating on patients who expect exact results and be careful in planning breast augmentation in tuberous breasts, where large asymmetries are present and if the breast is ptotic with poor tissue quality. Surgical complications with bleeding, pneumothorax and nerve damage could be minimized with careful planning and a meticulous surgical technique.

Early and late postoperative complications

Hematoma

This is an uncommon complication if a meticulous technique is used, but occurs in approximately 0.5-2% of cases.16–18 Hematomas should be evacuated, as even small hematomas may contribute to capsular contraction and wound dehiscence.

Seroma

Blunt dissection adds to the risk of seroma formation. With sharp dissection and by leaving the loose connective tissue on the ribs this problem can generally be avoided.14 Seromas may also occur late and be related to a sub-clinical infection (Fig. 16.16B). These should be drained and cultures taken before antibiotics are administered.

Infections and septic shocks

Patients receiving implantations should receive prophylactic antibiotics. For non-allergic patients the antibiotic of choice is flucloxacillin, ideally by IV, 20 minutes preoperatively. Giving antibiotics days before surgery or for longer periods post operatively is not indicated. One dose of flucloxacillin is sufficient. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin is the preferred drug. This regime almost entirely eliminates the risk for infections. If these occur, it is usually because of poor surgical techniques during wound closure. Infections should normally be treated with implant removal and a longer healing period before new implants are inserted.19

Asymmetries and implant malposition

Meticulous planning and surgical technique minimizes risk, but capsular contraction or poor tissue adhesion of anatomical textured implants may result in malposition or rotation. To minimize this risk, the pore size of the textured surface should be larger than 300 μm20,21 (Figs 16.16A & B & 16.17A-D).

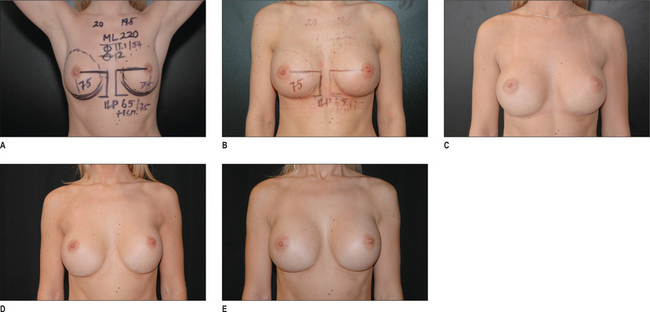

Fig. 16.17 A-D, Preoperative planning according to the ‘Akademikliniken-method’ (see description of Figures 16.9, 16.10 & 16.11). Note that arm elevation 45 ° over the head and drawing of a line from the nipple to the sternum simulates nipple position after the augmentation (B). C, 3 months later the implants have settled moderately, but 6 months later due to non-adhesion of the textured implants, too much descent of the implant is noted (D). Compare to opposite reaction due to capsular contraction in Figure 16.2. E, After implant exchange and insertion into new sub-muscular implant pocket, drainage and long-term fixation, a good long-term stable result has been achieved 1 year after the secondary correction.

Implant visibility, rippling, synmastia, perforation and implant extrusion

These are uncommon, but if implants are placed in the wrong position in relation to the covering muscle, with too poor tissue cover and/or are excessively large, they may be seen (Fig. 16.6A-D).

Double bubble deformity

This type of deformity of the lower pole of the breast may occur if the implant has to be placed significantly lower than the inframammary fold and the glandular tissue is contracted or tuberous. In a contracted breast with a short nipple inframammary fold distance, an implant with a dimension that exceeds the natural boundaries of the breast is usually necessary. To minimize the risk for double bubble deformity the gland has to be modified via radial incision or a creation of a glandular flap, to optimize the transition between implant and gland. Higher projecting and form-stable implants (e.g. Inamed Style 510 implants) also minimize the risk of double bubble deformity.

Deformations during pectoralis muscle contraction

For a natural-looking lower pole of the breast it is important to divide the origin of the pectoralis muscle, as above (Fig. 16.18A-E). By dual plane dissection II-IV, deformations of the breast during muscle contractions are minimized. It is important not to divide the pectoralis muscle too high along the sternum. The medial division should always end well below the height of the nipple areola complex. Especially in ptotic breasts, it is easy to over-dissect the inferior medial origin of the muscle. The preoperative markings of the nipple sternum lines (NS) are a valuable guideline.

Interference with the postoperative investigations

Breast implants always make mammograms more difficult to interpret, but by using, for example, Eklund’s examination, glandular tissue can be examined accurately. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most reliable way of investigating both the implant and the glandular tissue.22,23

Capsular contraction

This is the most common late complication.16,18 The frequency varies depending on the implant’s position. Most studies confirm that sub-muscular positioning minimizes capsular contractions, as do textured surfaces, especially in the sub-glandular plane. With modern techniques the frequency of capsular contraction is approximately 5-10%. This may vary from a slight firmness to a very hard, deformed and cold breast.24

Implant rupture

All implants may rupture, but the risk for this is greatly related to the generation of implant used and the duration of implantation. Generation two implants, mainly used in the 1970s, have a relatively high risk for rupture after more than 10 years.25,26 Third generation implants with a mean age of 11 years have been found to have a worst-case rupture prevalence of 8%27 (Fig. 16.19A). It appears that form-stable implants with high cohesive silicone gel have a very low rupture frequency, but these have only been used since 1994 and long-term risks are not finally proven. Implantation times between 5 and 9 years show risks of approximately 1%5 (Fig. 16.19B). Extravasation of silicone gel is uncommon and highly related to closed capsulotomy.23,24 This manoeuvre should be avoided.

Postoperative Care

Physical activity and exercise

Arm elevation is recommended directly after the procedure. Stretching the pectoralis muscle once every hour during the first 24 hours after the procedure minimizes postoperative pain in sub-muscular implantation. With proper surgical technique and infiltration of local anaesthesia around the breast, postoperative pain is normally minimal. With mild analgesic medication patients should be able to go home within 4-6 hours. Sports and vigorous physical activity should be avoided for approximately 3 weeks. Following this initial healing phase the patient can resume sports, but all sports that exert tension on the scar, or to much implant movement, such as serving in tennis or trampoline bouncing, should be avoided for 3 months. Vigorous stretching perpendicular to the scar may widen it during this period. To improve the final scar appearance, scars should be taped with paper tape (Micropore®) for up to 6 months. This helps the scar to mature and reminds the patient not to exert excessive tension.

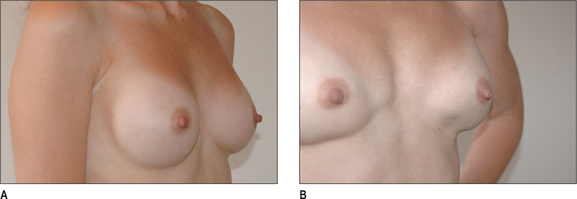

Conclusions

In breast augmentation surgery there are many alternative techniques and materials. Different implant shapes with surface variability are available and access to the surgical pocket can be through several different routes. All have advantages and drawbacks, but accurate planning is always essential (Fig. 16.20A & B). Implant selection and preoperative planning should not be arbitrary, but based on a meticulous analysis of biological prerequisites and implant dimensions. Good patient communication and meticulous planning minimizes the risk for re-operation and dissatisfaction and is the foundation for a longterm, stable result.

1. Kinsey A.C., Pomeroy W.B., Martin C.E. Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1948.

2. Beale S., Hambert G. Lisper Ho et al Augmentation mammoplasty: the surgical and psychological effect of the operation and prediction of the result. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:279-297.

3. Cash T., Duel L., Perkins L. Women psychosocial outcome of breast augmentation with silicone gel filled implants: a two year prospective study. Plast Recontruc Surg. 2002;109:2112.

4. Schlebusch L., Mahrt I. Long term psychological sequele of augmentation mammoplasty. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:267-271.

5. Hedén P., Boné B., Murphy D.K., Slitcom A., Walker P.S. Style 410 cohesive silicone breast implants. Safety and effectiveness at 5 to 9 years after implantation. Plast Reconst Surg. 2006;118:1281-1287.

6. Andersson R.C. Aesthetic surgery and psychosocial issues. Aesthetic Surgery Q. 1996;16(4):227-229.

7. Hedén P. Breast augmentation with anatomic, high-cohesiveness silicone gel implants. In: Spear S.L., editor. Surgery of the breast. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1344-1366.

8. Graf R.M., Bernardes A., Rippel R., Araujo L.R., Damasio R.C., Auersvald A. Subfascial breast implant: a new procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):904-908.

9. Tebbetts J.B. Dual plane breast augmentation: optimizing implant-soft-tissue relationships in a wide range of breast types. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(5):1255-1272.

10. Spear S.L., Carter M.E., Ganz J.C. The correction of capsular contracture by conversion to “Dual-Plane” positioning: technique and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(2):456-466.

11. Jones F.R., Tauras A.P. A periareolar incision for augmentation mammoplasty. Plast Reconst Surg. 1973;51:641.

12. Hoehler H. Breast augmentation: the axillary approach. Br J Plast Surg. 1973;26:373.

13. Johnson G.W., Christ J.E. The endoscopic breast augmentation: the transumbillical insertion of saline filled breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(5):801-808.

14. Tebbetts J.B. A system for breast implant selection based on patient tissue characteristics and implant-soft tissue dynamics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(4):1396. 411

15. Tebbetts J.B. Patient evaluation, operative planning, and surgical techniques to increase control and reduce morbidity and reoperations in breast augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28(3):501-521.

16. Heden P., Jernbeck J., Hober M. Breast augmentation with anatomical cohesive gel implants: the world’s largest current experience. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28(3):531-552.

17. Rheingold L.M., Yoo R.P., Courtiss E.H. Experience with 326 inflatable beast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(1):118. 112

18. Kjoller K., Holmich L.R., Jacobsen P.H., et al. Capsular contracture after cosmetic breast implant surgery in Denmark. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47(4):359-366.

19. Pittet B., Montandon D., Pittet D. Infection in breast implants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(2):94-106.

20. Danino A., Rocher F., Blanchet-Bardon C., Revol M., Servant J.M. A scanning electron microscopy study of the surface of porous-textured breast implants and their capsules. Description of the ‘velcro’ effect of porous-textured breast prostheses. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2001;46(1):23-30.

21. Danino A.M., Basmacioglu P., Saito S., Rocher F., Blanchet-Bardon C., Revol M., Servant J.M. Comparison of the capsular response to the biocell rtv and mentor 1600 siltex breast implant surface texturing: a scanning electron microscopic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(7):2047-2052.

22. Brown S.L., Silverman B.G., Berg W.A. Rupture of silicone-gel breast implants: causes, sequelae, and diagnosis. Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1531-1537.

23. Belli P., Romani M., Magistrelli A., Masetti R., Pastore G., Costantini M. Diagnostic imaging of breast implants: role of MRI. Rays. 2002;27(4):259-277.

24. Baker J. Classification of spherical contractures. Paper presented at the Aesthetic Breast Symposium in Scottsdate, Arizona. 1975.

25. Holmich L.R., Kjoller K., Vejborg I., et al. Prevalence of silicone breast implant rupture among Danish women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(4):848-858.

26. Holmich L.R., Kjoller K., Vejborg I., et al. Prevalence of silicone breast implant rupture among Danish women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(4):859-863.

27. Heden P., Nava M.B., van Tetering J.P., et al. Prevalence of rupture in INAMED silicone breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(2):303-308. discussion 309-312