CHAPTER 36 Breast Asymmetries

Summary/Key Points

Operative Technique

Case Studies

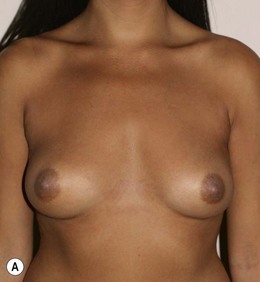

Case 1

Figure 36.1 (age 28) requesting ‘fuller larger perkier.’ Clinical finding: right breast evidently larger.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 870 cc, left 690 cc, difference 180 cc.

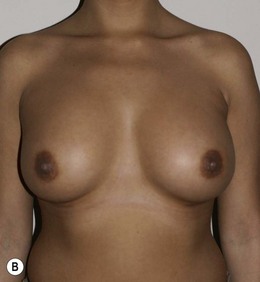

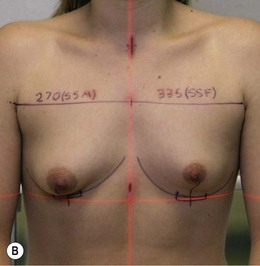

Case 2

Surgical plan: bilateral breast augmentation with different sizes, diameters and projections.

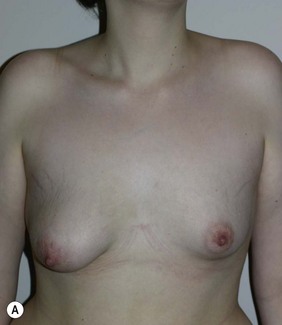

Figure 36.2 (age 35) requesting, ‘perky breasts and not look flat chested.’ Clinical finding: left breast smaller and nipple–areola a little higher.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 460 cc, left 400 cc, difference 60 cc.

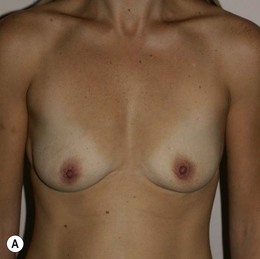

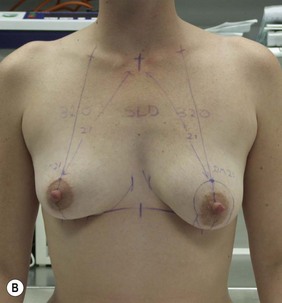

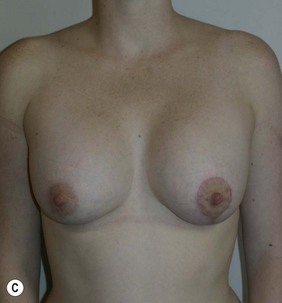

Case 3

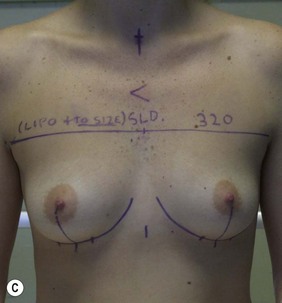

Figure 36.3 (age 22) requesting ‘breast augmentation.’ Clinical finding: Left breast smaller and left nipple–areola smaller and higher.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 520 cc, left 460 cc, difference 60 cc.

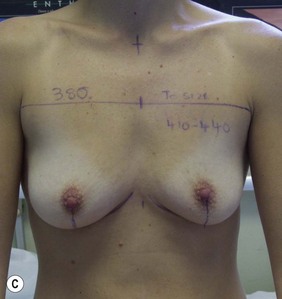

Case 4

Surgical plan: left mastopexy-augmentation and right breast augmentation.

Figure 36.4 (age 32) requesting ‘even, fuller breasts, size D.’ Clinical finding: left breast ptotic and slightly larger.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 680 cc, left 710 cc, difference 30 cc.

Case 5

Figure 36.5 (age 26) requesting ‘chest in proportion, breast enhancement, decrease the gap.’ Clinical finding: right breast evidently larger.

Case 6

Surgical plan: right breast liposuction

Figure 36.6 (age 38) requesting ‘even sized breasts and not fussed with size.’ Clinical finding: right breast significantly larger.

Water displacement test fairly consistently demonstrated an approximate 100 cc difference.

Case 7

Figure 36.7 (age 20) requesting ‘the asymmetry of my breasts.’ Clinical finding: right breast larger.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 1100 cc, left 670 cc, difference 440 cc.

Case 8

Surgical plan: breast reduction of large right breast with iatrogenic asymmetry.

Figure 36.8 (age 49) requesting ‘reduction of right breast.’ ‘At age 16 had left breast reduction, subsequently the right grew and for 32 years lived with uneven breast.’

Clinical finding: right breast significantly larger.

Water displacement test fairly consistently demonstrated an approximate 300 cc difference.

Operative detail: right breast reduction of 325 g with Wise pattern, inferior pedicle.

Case 9

Figure 36.9 (age 32) requesting ‘to not have the pain. To be a size D if possible.’

Clinical finding: both breasts large with the right breast fuller laterally and a little larger.

Case 10

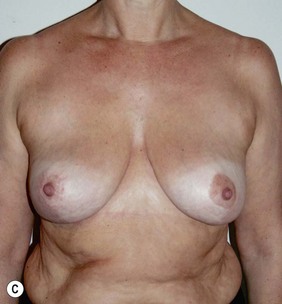

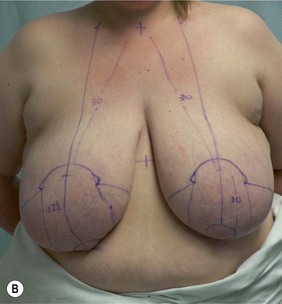

Surgical plan: bilateral breast reduction (very substantial) with greater reduction of the right.

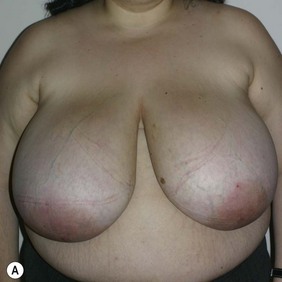

Figure 36.10 (age 25) requesting, ‘reduce breast size to prevent damage to back.’

Case 11

Figure 36.11 (age 20) requesting ‘have symmetrical breasts through implants.’

Clinical finding: left breast small and ptotic, right breast significantly smaller but not ptotic.

Water displacement test fairly consistently demonstrated an approximate 70 cc difference.

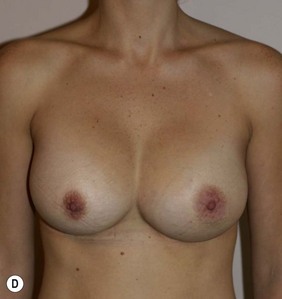

Case 12

Surgical plan: bilateral breast augmentation with simultaneous left breast reduction

Figure 36.12 (age 37) requesting ‘even breasts, unsure of enlargement or reduction.’

Clinical finding: left breast larger and more ptotic with lower inframammary crease.

Water displacement test suggested the left breast 150–200 cc larger.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 530 cc, left 730 cc, difference 200 cc.

Case 13

Surgical plan: multistaged complex correction.

Figure 36.13 (age 22) requesting ‘very asymmetric, want them even, probably enlarge the smaller.’

Clinical finding: significant complex asymmetries.

The water displacement test measured 250 cc difference.

Breast volumes as reported by MRI: right 550 cc larger than left.

Comment: staged surgeries may be preferable in the correction of complex asymmetries.

Araco A, Gravante G, Araco F, et al. Breast asymmetries: a brief review and our experience. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30(3):309-319.

Bruschi S, Bogetti P, Bocchiotti MA, et al. Congenital mammary asymmetry. Classification and surgical treatment. Ann Ital Chir. 2007;78(3):177-182.

De Paredes ES. Atlas of mammography. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Dixon JM, editor. ABC of breast diseases. BMJ Books/Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Kuzbari R, Deutinger M, Todoroff BP, Schneider B, Freilinger G. Surgical treatment of development asymmetry of the breast. Long term results. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1993;27(3):203.

Rees TD. Mammary asymmetry. Clin Plast Surg. 1975;2(3):371-374.

Reilley AF. Breast asymmetry: classification and management. Aesth Surg J. 2006;26(5):596.

Rintala AE, Nordstrom REA. Treatment of severe developmental asymmetry of the female breast. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1989;23(3):231-235.

Sakai S. Treatment of congenital breast asymmetry. Jpn J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;44(7):675.

Sandsmark M, Amland PF, Samdal F, Skolleborg K, Abyholm F. Clinical-results in 87 patients treated for asymmetrical breasts: a follow-up-study. Scand J Plastic Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1992;26(3):321-326.

Seyfer AE, Icocheas R, Graeber GM. Poland’s anomaly. Natural history and long-term results of chest wall reconstruction in 33 patients. Ann Surg. 1988;208(6):776-782.

Smith DJJr, Palin WEJr, Katch V, Bennett JE. Surgical treatment of congenital breast asymmetry. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;17(2):92.