57 Brain Tumors

Clinical Presentation

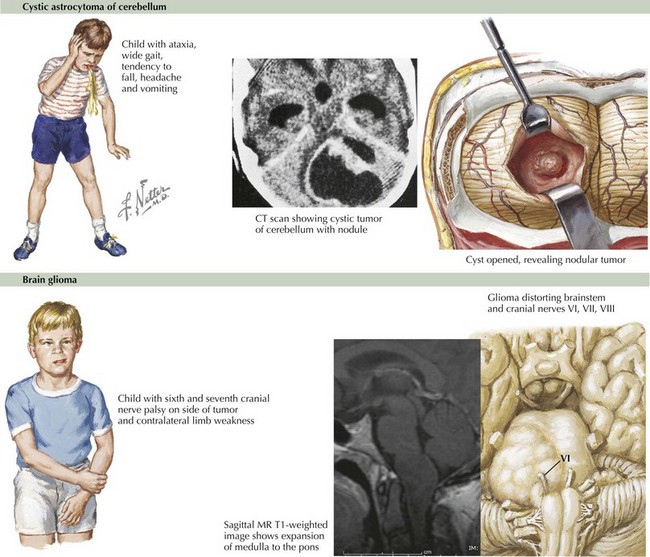

The presenting symptoms of a brain tumor are determined by tumor location rather than histology. Brain tumors may present with either generalized or localizing symptoms. Generalized symptoms are caused by obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with associated hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Increased ICP is more common with fourth ventricular or posterior fossa, pineal, suprasellar, and tectal tumors. Symptoms include headache (particularly in the morning), nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. On examination, paresis of upgaze, sixth cranial nerve palsies, and papilledema are often seen. In infants, macrocephaly, tense fontanelle, failure to thrive, developmental delay, and paresis of upgaze with downward eye deviation (“sun setting”) are common. Posterior fossa tumors, such as cerebellar astrocytomas, often present with increased ICP (Figure 57-1).

Localizing symptoms depend on tumor location. Cerebellar tumors commonly present with ataxia and dysmetria. Brainstem tumors may cause cranial nerve deficits (diplopia, facial weakness, swallowing deficits), unsteadiness, and weakness (see Figure 57-1). Symptoms from hemispheric cortical tumors include seizures, hemiparesis, visual field deficits, and changes in behavior or school performance. Tumors in the suprasellar region often present with bitemporal visual field loss, decreased acuity, and hormonal dysfunction. Pineal region tumors frequently compress the tectal region of the brainstem and result in Parinaud’s syndrome, characterized by paresis of upgaze, convergence nystagmus, pupils that respond better to accommodation than light (light-near dissociation), and eyelid retraction. Tumors of the spinal cord (primary or metastatic) may cause back pain, extremity weakness, sensory dysfunction, and bowel or bladder dysfunction. The most common presenting signs and symptoms are outlined in Table 57-1.

Table 57-1 Signs and Symptoms Associated with Intracranial Tumors

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation can aid in localizing a brain tumor, and the anatomic location of a mass often narrows the differential diagnosis of the tumor type. Histologic confirmation is necessary in nearly all brain tumor cases with the exception of diffuse intrinsic brainstem (pontine) glioma, tectal glioma, and optic pathway gliomas in patients with NF1, in which neuroimaging alone can be sufficient for diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of brain tumors according to intracranial location is presented in Table 57-2.

Table 57-2 Differential Diagnosis of Brain Tumors by Location

| Location | Tumor |

|---|---|

| Cerebral hemisphere | Glioma Ependymoma PNET |

| Pineal | Germ cell tumor Glioma (tectal glioma) Pineoblastoma Pineocytoma |

| Cerebellum | Pilocytic astrocytoma Medulloblastoma Ependymoma |

| Brainstem | Glioma |

| Suprasellar | Craniopharyngioma Visual (optic) pathway glioma Germ cell tumor Pituitary tumor |

| Spinal Cord | Astrocytoma Ependymoma |

PNET, primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Evaluation And Management

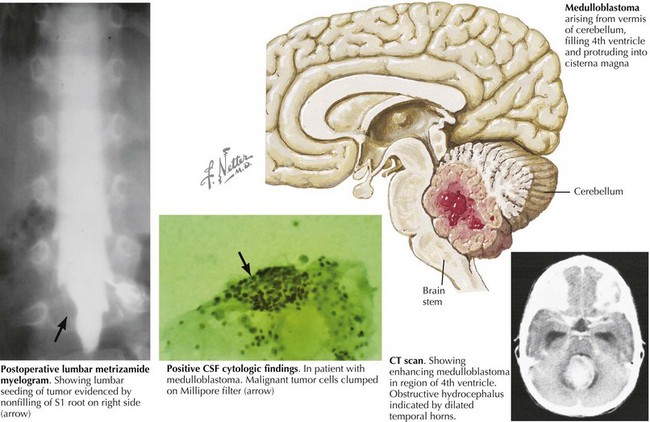

After surgery and histologic diagnosis, further studies are needed to stage the tumor. A postoperative MRI with and without gadolinium should be done within 24 to 48 hours after surgery to determine if residual tumor remains. The MRI must be repeated within this time frame so postoperative inflammatory changes are not confused for residual tumor or vice versa. For tumors with a high likelihood of spread via the CSF, complete multiplanar spine MRI and large-volume lumbar puncture for cytology should be performed. Medulloblastoma, the most common malignant tumor in children, must be evaluated in this fashion (Figure 57-2). CSF and serum for the tumor markers α-fetoprotein and quantitative β-HCG should be sent if a germ cell tumor is diagnosed. Last, laboratory assessment of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis should be evaluated for any tumor involving the suprasellar region. Panhypopituitarism, including life-threatening diabetes insipidus, can be a relatively common postoperative complication in these children.

Treatment is tailored to specific tumor type and patient age. In general, regardless of tumor type, radiation therapy is avoided in infants and very young children because they are especially vulnerable to radiation-associated toxicities and neurocognitive deficits. Alternative therapies for this population include intensified chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant. For some brain tumors (e.g., low-grade gliomas), complete surgical resection may be the only therapy indicated. Common pediatric tumors with their relative incidences and prognoses are outlined in Table 57-3.

Table 57-3 Common Pediatric Brain Tumors: Incidences, and Prognoses

| Tumor | Relative Incidence (%) | Prognosis (Overall Survival, 5 Years) |

|---|---|---|

| Low-grade glioma | 35-50 | 90%-100% (pilocytic astrocytoma with complete resection) 60%-90% (other subtypes) |

| Medulloblastoma or PNET | 16-20 | 85% overall (varies with age and stage) 20%-60% (infants) 33%-65% (supratentorial PNET) |

| Brainstem glioma | 10-20 | Median survival time, 9-13 mos (diffuse intrinsic pontine tumors) 80%-90% (localized tumors) |

| Ependymomas | 8-10 | 67%-80% (complete resection + XRT) 22%-47% (incomplete resection + XRT) |

| Malignant glioma | 10 | 25% (complete resection + XRT) |

| Germ cell tumors | 4-7 | Mature teratoma: 100% with complete resection Pure germinoma: >90% with surgery + radiation Nongerminomatous: 25%-55% with surgery + chemotherapy + XRT |

| Craniopharyngioma | 3 | 95% |

| Aggressive infantile embryonal tumors (i.e., atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor) | 3 | <10%-20% |

PNET, primitive neuroectodermal tumor; XRT, radiation therapy.

Abdullah S, Qaddoumi I, Bouffet E. Advances in the management of pediatric central nervous system tumors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1138:22-31.

Babcock MA, Kostova FV, Guha A, et al. Tumors of the central nervous system: clinical aspects, molecular mechanisms, unanswered questions, and future research directions. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1103-1121.

Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States: Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2000-2004. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States, 2008.

Packer RJ, MacDonald T, Vezina G. Central nervous system tumors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:121-145.