CHAPTER 11 BRAIN INJURY, NEUROLOGICAL AND NEUROMUSCULAR PROBLEMS

PATTERNS OF BRAIN INJURY

The brain is extremely susceptible to injury from a variety of causes, but particularly from the effects of trauma, hypoxia, and hypoperfusion. Typical causes and patterns of brain injury are shown in Table 11.1.

| Traumatic brain injury | Diffuse swelling Diffuse axonal injury Acute intracerebral haematoma Acute subdural haematoma Acute extradural haematoma Contusions (bruising) Chronic subdural haematoma |

| Spontaneous haemorrhage | Subarachnoid haemorrhage Intracerebral haemorrhage |

| Cerebrovascular disease (embolic) | Stroke |

| Infection | Meningitis, encephalitis, abscess |

| Hypoxic / ischaemic injury | Watershed infarction Global infarction Hypoxic encephalopathy |

| Metabolic | Encephalopathy |

KEY CONCEPTS IN BRAIN INJURY

The principles of management are therefore to:

Cerebral blood flow and autoregulation

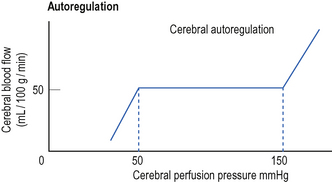

Cerebral blood flow is normally maintained at a constant level over a wide range of cerebral perfusion pressures, a phenomenon known as autoregulation (Fig. 11.1). In normotensive patients, autoregulation occurs at cerebral perfusion pressures between 50 and 150 mmHg. In previously hypertensive patients, the curve is shifted to the right and autoregulation occurs at a higher blood pressure.

Cerebral perfusion pressure

Central venous pressure is sometimes included in this equation. This is because the cranium behaves as a Starling resistor – so where the CVP exceeds the ICP, the CVP becomes the effective downstream pressure and should be used to calculate CPP.

Inadequate CPP results in inadequate cerebral blood flow and the maintenance of an adequate CPP is therefore crucial. However, there is debate about what constitutes an adequate CPP and what the target values for therapy should be. Typical target values are shown in Table 11.2.

TABLE 11.2 Typical target values for cerebral perfusion (mmHg)*

| Adults | > 60 |

| 3–12 years | > 50 |

| < 3 years | > 40 |

* There is debate about the ideal target values. Some accept lower target values.

IMMEDIATE MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

The following notes relate to the management of traumatic brain injury. The principles apply equally well to the management of other forms of brain injury.

Airway (with cervical spine control)

The maintenance of a clear airway and the prevention of hypoxia and hypercapnia are paramount. Indications for intubation and ventilation are shown in Box 11.1.

Box 11.1 Indications for intubation and ventilation of brain-injured patient

GCS less than 8 or falling rapidly

Hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 6.5 kPa), or hypocapnia (PaCO2 < 3.0 kPa)

Inability to protect the airway

Significant facial injuries and bleeding (swelling may make intubation very difficult if delayed)

Major injuries elsewhere, especially chest injuries

Evidence of shock state (tachycardia, low BP, acidosis, etc.)

A restless patient who requires transfer to CT

Any patient with a significant brain injury requiring interhospital transfer

Intubation/ventilation of brain-injured patients

(See Practical procedures: Intubation of the trachea, p. 398.)

Establish intravenous access. Give volume loading, particularly if there is haemorrhage and other injuries. Blood, colloid or crystalloid is used as appropriate. If possible, establish direct arterial pressure monitoring.

Check all intubation equipment, breathing circuits, ventilators and suction, etc. Monitoring should be available for BP, ECG, SaO2 and ETCO2.

Check all intubation equipment, breathing circuits, ventilators and suction, etc. Monitoring should be available for BP, ECG, SaO2 and ETCO2. Note the baseline GCS score and pupil size for reference. The pupils are the principal clinical monitor of the brain following anaesthesia and paralysis.

Note the baseline GCS score and pupil size for reference. The pupils are the principal clinical monitor of the brain following anaesthesia and paralysis. Assume there is cervical spine injury until proved otherwise. A second person should provide in-line immobilization of the neck. (It may be useful to use a bougie / airway exchange catheter / video laryngoscope to facilitate intubation without extending the neck.)

Assume there is cervical spine injury until proved otherwise. A second person should provide in-line immobilization of the neck. (It may be useful to use a bougie / airway exchange catheter / video laryngoscope to facilitate intubation without extending the neck.) Assume the stomach is full and perform a rapid sequence induction. Preoxygenate with 100% oxygen. Ask a trained assistant to apply cricoid pressure. Use etomidate if the BP is low, otherwise thiopentone or propofol are suitable induction agents. Suxamethonium is used to provide muscle relaxation (unless absolutely contraindicated, see p. 43).

Assume the stomach is full and perform a rapid sequence induction. Preoxygenate with 100% oxygen. Ask a trained assistant to apply cricoid pressure. Use etomidate if the BP is low, otherwise thiopentone or propofol are suitable induction agents. Suxamethonium is used to provide muscle relaxation (unless absolutely contraindicated, see p. 43). Opioid, e.g. fentanyl 100 μg increments or remifentanil by infusion, 0.1 μg kg−1 min−1 can be used to help block the hypertensive response to intubation.

Opioid, e.g. fentanyl 100 μg increments or remifentanil by infusion, 0.1 μg kg−1 min−1 can be used to help block the hypertensive response to intubation. Ventilate to normocapnia or moderate hypocapnia (PaCO2 4–4.5 kPa). Significant hypocapnia is associated with cerebral vasoconstriction and reduced cerebral perfusion. This may potentially cause cerebral ischaemia and worsen brain injury.

Ventilate to normocapnia or moderate hypocapnia (PaCO2 4–4.5 kPa). Significant hypocapnia is associated with cerebral vasoconstriction and reduced cerebral perfusion. This may potentially cause cerebral ischaemia and worsen brain injury. Monitor the SaO2 and ETCO2. Measure direct arterial blood pressure and blood gases as soon as possible. Maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure with fluids and vasoactive drugs (see below).

Monitor the SaO2 and ETCO2. Measure direct arterial blood pressure and blood gases as soon as possible. Maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure with fluids and vasoactive drugs (see below). Maintain sedation with benzodiazepines, propofol and opioids. During the early resuscitation and stabilization phase continue paralysis with a cardiovascularly stable non-depolarizing muscle relaxant.

Maintain sedation with benzodiazepines, propofol and opioids. During the early resuscitation and stabilization phase continue paralysis with a cardiovascularly stable non-depolarizing muscle relaxant.Circulation

It is vital to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure in brain-injured patients:

Give colloid or normal saline to restore circulating volume. Avoid hyponatraemic fluids as these worsen outcome.

Give colloid or normal saline to restore circulating volume. Avoid hyponatraemic fluids as these worsen outcome.Conscious level

The simplest assessment of conscious level utilizes a four-point scale:

This score is insufficiently sensitive for neurological assessment of the brain-injured patient and is only used during A&E resuscitation to give a broad indication of conscious level. Response to pain only represents a significant decrease in conscious level equivalent to a GCS score of 8 or less.

The Glasgow Coma Scale

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), shown in Table 11.3, is a more comprehensive neurological assessment, which is universally used to describe conscious level and has prognostic value. It should be performed as soon as the patient is stabilized. It is repeated throughout the resuscitation process to identify any deterioration in the patient’s condition, which may suggest expanding intracerebral haematoma or brain swelling.

| Eye opening | Spontaneously To speech To pain None |

4 3 2 1 |

| Best verbal response | Orientated Confused Inappropriate words Incomprehensible sounds None |

5 4 3 2 1 |

| Best motor response (arms) | Obeys commands Localization to pain Normal flexion to pain Spastic flexion to pain Extension to pain None |

6 5 4 3 2 1 |

Maximum score 15. Minimum score 3. (A modified GCS is used for children under 5 years)

Reassessment and secondary survey

Having completed a primary survey and stabilized the patient, the patient should be reassessed before moving on to secondary survey. Traumatic brain injury may be an isolated injury, but this should never be assumed. The care of the brain injury must proceed alongside the continuing re-evaluation and resuscitation of the other injuries according to ATLS protocols. In particular, remember:

INDICATIONS FOR CT SCAN

CT scan should not be delayed by taking plain X-rays. Indications for CT scan are shown in Table 11.4.

| All patients with moderate / severe injury plus any of the following: | GCS < 13 Neurological signs Inability to assess conscious level, e.g. due to anaesthetic drugs |

| Any patient with mild injury plus any of the following: | High-risk mechanism of injury GCS < 15 for more than 2 h Skull fracture Vomiting Age > 60 years* |

* High risk patient group for occult intracranial injury

CT normal or minimal changes only: stop sedative drugs; allow the patient to wake up and reassess neurological state.

CT normal or minimal changes only: stop sedative drugs; allow the patient to wake up and reassess neurological state. CT diffuse or non-operable injury (e.g. diffusely swollen brain): admit patient to ICU for further management, including monitoring of ICP.

CT diffuse or non-operable injury (e.g. diffusely swollen brain): admit patient to ICU for further management, including monitoring of ICP.INDICATIONS FOR NEUROSURGICAL REFERRAL

The facilities available for dealing with the head-injured patient vary. Hospitals may have no CT scanner, a CT scanner but no neurosurgery, or all facilities. The decision to transfer a patient will therefore be influenced not only by the patient’s condition, but also by the local availability of resources. Indications for referral are summarized in Box 11.2.

Box 11.2 Indications for referral to neurosurgical centre

CT scan indicated but not available locally

CT scan shows intracranial haemorrhage/midline shift

CT scan suggests diffuse axonal injury

CT scan suggests raised intracranial pressure/hydrocephalus

Identification of a vacant ICU bed space should not delay transfer of patients, who require an urgent CT scan or craniotomy for evacuation of a haematoma. Most neurosurgical units try to adopt an open admission policy, taking all seriously injured patients who have not had a CT scan and those who require operative intervention, regardless of the availability of ICU beds. Once appropriate interventions have been performed, any delay in finding an intensive care bed will not place the patient at further significant risk. Patients can if necessary be transferred back to the referring hospital once the need for further intervention has been excluded.

ICU MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

Use tracheal intubation and assisted ventilation to maintain adequate oxygenation and normocapnia, or mild hypocapnia (PaCO2 4–4.5 kPa).

Use tracheal intubation and assisted ventilation to maintain adequate oxygenation and normocapnia, or mild hypocapnia (PaCO2 4–4.5 kPa). Maintain adequate sedation and analgesia. Paralysis is usually required in the early phases of treatment but should only be continued in unstable patients, those with raised intracranial pressure or when required to enable satisfactory ventilation.

Maintain adequate sedation and analgesia. Paralysis is usually required in the early phases of treatment but should only be continued in unstable patients, those with raised intracranial pressure or when required to enable satisfactory ventilation. Nurse the patient 15–20° head-up to ensure adequate venous drainage. Avoid tight tapes to secure endotracheal tube, which may occlude jugular veins.

Nurse the patient 15–20° head-up to ensure adequate venous drainage. Avoid tight tapes to secure endotracheal tube, which may occlude jugular veins. Establish monitoring. Arterial blood pressure and CVP, urinary catheter, NG tube. If possible avoid internal jugular routes of cannulation (except for jugular bulb cannula). Insertion difficulties may impair cerebral venous drainage and also risk carotid injury. Use ultrasound guidance in all cases to avoid arterial puncture and other complications. The femoral route has some advantages, avoiding the need for head-down tilt during insertion.

Establish monitoring. Arterial blood pressure and CVP, urinary catheter, NG tube. If possible avoid internal jugular routes of cannulation (except for jugular bulb cannula). Insertion difficulties may impair cerebral venous drainage and also risk carotid injury. Use ultrasound guidance in all cases to avoid arterial puncture and other complications. The femoral route has some advantages, avoiding the need for head-down tilt during insertion. Give maintenance fluids as 0.9% saline (plus K+) initially. In the past maintenance fluids were restricted, but maintenance of cerebral perfusion is now considered paramount. Hyponatraemia and hyperglycaemia worsen outcome and should be avoided. Hypertonic saline (3–7.5%) have been used as boluses. Follow local protocols.

Give maintenance fluids as 0.9% saline (plus K+) initially. In the past maintenance fluids were restricted, but maintenance of cerebral perfusion is now considered paramount. Hyponatraemia and hyperglycaemia worsen outcome and should be avoided. Hypertonic saline (3–7.5%) have been used as boluses. Follow local protocols. Prevent a rise in temperature. Give regular paracetamol and use surface cooling (tepid sponges, fans, cool air blankets. There may be some benefit from mild hypothermia 35.5–36.5°C.

Prevent a rise in temperature. Give regular paracetamol and use surface cooling (tepid sponges, fans, cool air blankets. There may be some benefit from mild hypothermia 35.5–36.5°C. Stress ulcer prophylaxis. Commence enteral feeding as soon as practicable. Otherwise an H2 antagonist or proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed.

Stress ulcer prophylaxis. Commence enteral feeding as soon as practicable. Otherwise an H2 antagonist or proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed.Maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)

Titrate fluid therapy according to CVP. If there is no improvement or if the patient is haemodynamically unstable, consider the use of advanced haemodynamic monitoring devices (optimize cardiac output, stroke volume, vascular resistance etc.).

Titrate fluid therapy according to CVP. If there is no improvement or if the patient is haemodynamically unstable, consider the use of advanced haemodynamic monitoring devices (optimize cardiac output, stroke volume, vascular resistance etc.). After adequate fluid resuscitation, if CPP remains low, use vasopressors, e.g. noradrenaline (norepinephrine) or phenylephrine to increase mean arterial pressure and improve CPP.

After adequate fluid resuscitation, if CPP remains low, use vasopressors, e.g. noradrenaline (norepinephrine) or phenylephrine to increase mean arterial pressure and improve CPP.Control of intracranial pressure (ICP)

Normal ICP is less than 10 mmHg and a sustained pressure higher than 20 mmHg is associated with poorer outcomes. If ICP is greater than 20–30 mmHg then intervention may be necessary, particularly in the first 24–48 h following injury. Table 11.5 provides a checklist of causes of a raised ICP. Exclude measurement errors and avoidable rises before starting treatment.

| Problem | Action |

|---|---|

| Accuracy of measurement | Reposition, flush and recalibrate device. |

| Inadequate sedation or paralysis | Give a bolus of sedation, analgesia and / or relaxants. Increase infusion rates. |

| Hypoxia or hypercapnia | Check Et CO2 / blood gases. Adjust FiO2 and / or ventilation as necessary. |

| Inadequate CPP | Consider additional i.v. fluids. Increase vasopressors / inotropes. |

| Impaired venous drainage from head and neck | Head turned (occluding neck veins). Endotracheal tube tapes too tight. Nurse 15–20° head up. |

| Seizures | May be masked by muscle relaxants. Check CFM trace or EEG. Treat appropriately. |

| Pyrexia | Give antipyretics. Consider surface cooling. |

1st line

Mannitol 0.5 g / kg over 20 min, and / or furosemide (frusemide) 0.5 mg / kg. Any benefit tends to be temporary.

Mannitol 0.5 g / kg over 20 min, and / or furosemide (frusemide) 0.5 mg / kg. Any benefit tends to be temporary.2nd line

Thiopental (thiopentone) infusion. 15 mg / kg 1st hour, 8 mg / kg 2nd hour, 5 mg / kg / h thereafter. The aim is to achieve burst suppression on CFM monitoring. The disadvantage of this approach is that the time taken for thiopental to wear off once the infusion is stopped delays the ability to clinically assess the patient. Monitor levels over time.

Thiopental (thiopentone) infusion. 15 mg / kg 1st hour, 8 mg / kg 2nd hour, 5 mg / kg / h thereafter. The aim is to achieve burst suppression on CFM monitoring. The disadvantage of this approach is that the time taken for thiopental to wear off once the infusion is stopped delays the ability to clinically assess the patient. Monitor levels over time.COMMON PROBLEMS IN TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

Cardiovascular instability

Haemodynamic instability is common and may be seen in association with neurogenic pulmonary oedema (see below). The importance of an adequate cerebral perfusion pressure has already been stressed. Hypotension may be due to a combination of factors. You should exclude causes such as hypovolaemia, pneumothorax and sepsis. All patients should have direct arterial pressure and CVP monitoring. In complex cases, consider other monitoring devices to guide fluids, inotropes and vasopressor therapy, as for any shock state.

Seizures

If in doubt about the presence or absence of seizure activity in the paralysed patient request a formal EEG. Alternatively, there is usually little harm in temporarily reducing / stopping muscle relaxants to assess seizure activity; ensure adequate doses of sedative / analgesic drugs first!

1st line treatment

Intravenous benzodiazepines, e.g. diazepam 5–10 mg or clonazepam as necessary. Large cumulative doses may be needed. Midazolam is also effective.

Intravenous benzodiazepines, e.g. diazepam 5–10 mg or clonazepam as necessary. Large cumulative doses may be needed. Midazolam is also effective.2nd line treatment

If seizure activity is not controlled, then additional anticonvulsant agents such as clonazepam, sodium valproate, phenobarbital, clormethiazole, paraldehyde or magnesium may be required. Seek expert advice and check dose regimens in BNF.

If seizure activity is not controlled, then additional anticonvulsant agents such as clonazepam, sodium valproate, phenobarbital, clormethiazole, paraldehyde or magnesium may be required. Seek expert advice and check dose regimens in BNF.Diabetes insipidus (DI)

Neurogenic pulmonary oedema

Pulmonary oedema is a well-recognized complication of brain injury. In its severest form, it is characterized by extreme cardiovascular instability with profuse pink frothy pulmonary oedema. Simplistically, it is thought to result from a catecholamine surge caused by a rapid rise in ICP. This results in an acute increase in left ventricular afterload and left ventricular dysfunction, increased pulmonary vascular volume (blood returned from peripheries) pulmonary hypertension and increased permeability of pulmonary vascular endothelium, all of which may contribute to the development of oedema.

MONITORING MODALITIES IN BRAIN INJURY

You may encounter a number of monitoring modalities that are currently either routinely used or under evaluation in brain injury. Most are intended to provide additional information regarding perfusion, oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption in the brain. The majority of these techniques are limited either by technical difficulties or by inability to detect small, critically ischaemic areas within the brain. The overall outcome benefit is still debated.

Near infrared spectroscopy

This technique uses light absorption to measure brain tissue oxygenation. Light of a particular wavelength is passed through the skull and the absorption by brain cytochrome aa3 (representing the terminal step of the mitochondrial electron transport chain) is detected. The technique is limited by the depth to which the incident light is able to penetrate effectively. Changes probably reflect perfusion / oxygen delivery in superficial areas of the brain only.

OUTCOME FOLLOWING BRAIN INJURY

Following severe brain injury, patients typically require tracheal intubation, assisted ventilation and sedation / paralysis. Cerebral perfusion pressure and other parameters are optimized for a period of 48–72 h in the hope of minimizing secondary brain injury. If after this they remain unstable, have raised ICP or other ongoing system failure, further time will be required to allow for the patient’s condition to improve. Otherwise, a decision is usually made to stop sedatives and to allow patients to waken, so that their neurological status can be assessed.

Outcome following brain injury depends on a number of factors, including the mechanism and severity of the initial injury, subsequent episodes of hypotension, hypoxia or hypercapnia, adequacy of resuscitation, and the presence of other injuries. Age is important, young patients have a substantially better outcome than elderly patients for a given injury. In particular, young children may make a good recovery from an apparently devastating injury. There is a wide spectrum from mild to devastating injury. The Glasgow Outcome Scale (Table 11.6) can be used to classify outcomes.

| Description | Classification |

|---|---|

| Return to pre-injury levels of function | Good recovery |

| Neurological deficit but self-caring | Moderately disabled |

| Unable to self care | Severely disabled |

| No higher mental function | Vegetative |

| Dead |

It is relatively easy to predict outcomes at either end of the spectrum but not in between. The passage of time (weeks / months) is essential to assess potential for recovery. Clinicians learn from experience that it is often impossible to predict longer-term outcome in any individual patient. Furthermore, even apparently good physical recovery may mask subtle underlying cognitive deficits or psychological impairment and these problems may be manifest even after apparently trivial injuries.

SUBARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE

Management and outcome is determined by grading. Two common grading systems are shown in Table 11.7 and Table 11.8. Grading is difficult once the patient is sedated / ventilated. Rebleeding or vasospasm may rapidly worsen neurological state.

TABLE 11.7 Hunt and Hess grading system for subarachnoid haemorrhage

| Description | Grade |

|---|---|

| Unruptured aneurysm | 0 |

| Asymptomatic, minimal headache or nuchal rigidity | 1 |

| Moderate headache or nuchal rigidity | 2 |

| Moderate headache or nuchal rigidity | 2 |

| No neurological defi cit except cranial nerves. Drowsiness, confusion or mild focal deficit | 3 |

| Stupor, hemiparesis | 4 |

| Deep coma, decerebrate rigidity, moribund appearance | 5 |

TABLE 11.8 World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale

| Glasgow Coma Scale | Motor deficit | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | No | 1 |

| 13–14 | No | 2 |

| 13–14 | Yes | 3 |

| 7–12 | Yes or no | 4 |

| 3–6 | Yes or no | 5 |

Management

Definitive management is either by embolization of the aneurysm under radiological control or surgical clipping depending on the nature of the lesion. Timing depends upon the patient’s age (increasing risk of cerebrovascular disease and cerebral infarction) preoperative status and the perceived risk of rebleeding. Early intervention reduces the risk of rebleeding and of intercurrent medical problems, but where surgical intervention is required is technically more difficult and is associated with an increased risk of cerebral vascular spasm. Delayed intervention (10–14 days post-bleed) is technically easier and carries less risk of vasospasm, but increases the risk of bleeding in the intervening period.

ICU management

Maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure using fluids and vasopressors is crucial. Aim for mean systemic pressure of 90–100 mmHg. It is not usual to monitor ICP. Vasopressor therapy is usually used and may be required for up to 3 weeks.

Maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure using fluids and vasopressors is crucial. Aim for mean systemic pressure of 90–100 mmHg. It is not usual to monitor ICP. Vasopressor therapy is usually used and may be required for up to 3 weeks.HYPOXIC BRAIN INJURY

Patients who are resuscitated following cardiac arrest are usually referred for intensive care because of a failure to regain consciousness, haemodynamic instability or inadequate respiratory effort. There is little evidence that a period of elective ventilation, or the use of so-called cerebral protection agents (e.g. barbiturates / steroids), affect neurological outcome. Recent guidelines however, support the provision of moderate hypothermia in the management of the post-arrest situation, and this requires a period of artificial ventilation. Limited trials have shown encouraging results, but the optimum duration or degree of cooling is not yet known.

The emphasis should be on prevention of secondary insults.

Ventilate for 12–24 h, with minimal sedation where possible, then reassess neurological state. If the patient begins to get agitated then short-acting agents, e.g. propofol, allow subsequent periodic reassessment of neurology.

Ventilate for 12–24 h, with minimal sedation where possible, then reassess neurological state. If the patient begins to get agitated then short-acting agents, e.g. propofol, allow subsequent periodic reassessment of neurology. Purposeful or semi-purposeful movements are a good sign and usually herald recovery. Absence of respiratory effort, myoclonic jerking and fixed dilated pupils usually indicate severe hypoxic damage and a poor long-term outlook.

Purposeful or semi-purposeful movements are a good sign and usually herald recovery. Absence of respiratory effort, myoclonic jerking and fixed dilated pupils usually indicate severe hypoxic damage and a poor long-term outlook.(See Management of patients following cardiac arrest, p. 109.)

Infection

Meningitis

It is unusual for adults to require intensive care when meningitis is the primary presenting diagnosis. In the case serious enough to warrant intensive care it is advisable to perform CT scan prior to lumbar puncture to exclude cerebral oedema and the potential risk of coning after lumbar puncture. If lumbar puncture is contraindicated, empirical antibiotic therapy is then started. Steroids have been shown to reduce longer-term neurological sequelae in both adults and children presenting with Haemophilus, pneumococcal and recently meningococcal meningitis and should be given on presentation.

SEIZURES

Seizures are common in the critically ill, either as a presenting diagnosis of epilepsy or as a secondary complication of other disorders. Some of the more common predisposing factors are listed in Box 11.3.

Box 11.3 Conditions predisposing to seizure activity

Worsening of existing seizure disorder

Alcohol or other drug withdrawal

Drug overdose, e.g. tricyclic antidepressants

Status epilepticus

Status epilepticus can be defined as seizures lasting longer than 30 min, or so frequently that no recovery occurs between attacks. Patients are at risk of brain injury, cerebral oedema, hypoxia and aspiration. Typically, intensive care referral occurs when first-line drug treatment has failed and the patient becomes increasingly obtunded due to the effects of ongoing seizures and sedative drug accumulation. If untreated, patients may suffer further complications from immobility, hypothermia, hyperthermia and rhabdomyolysis.

BRAINSTEM DEATH

Brainstem death is caused by irreversible damage to the brainstem, which is the control centre for the autonomic functions of the brain. Its description in 1959 followed the introduction of assisted ventilation in brain-injured patients. Criteria for the diagnosis of brainstem death were first proposed in the UK in 1976 and an updated code of practice for the diagnosis and confirmation of death (including brainstem death) has recently been produced by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death, 2008).

Preconditions

Before brainstem tests are performed, there are a number of preconditions that must be satisfied in order to exclude potentially reversible causes of brainstem dysfunction. These are shown in Box 11.4.

Box 11.4 Preconditions to performing brainstem death tests

Known cause of brain damage, e.g. trauma, intracerebral haemorrhage, hypoxia

Absence of neuromuscular blocking drugs

Absence of any residual CNS depressant drugs

Normothermia (core temperature > 35.5°C)

Before performing tests ensure that all preconditions are satisfied. Always confirm the integrity of the neuromuscular junction and exclude the effects of muscle relaxants by use of a nerve stimulator (see p. 43). Scrutinize the drug chart and intensive care chart to ensure that sufficient time has elapsed for any centrally acting drugs to have been metabolized and eliminated. Beware of active metabolites, which may have long half-lives. If in doubt, drug levels can be measured. Check the patient’s core temperature and recent biochemistry results.

Conduct of brainstem death tests

Most hospitals will have pre-printed documentation for brainstem death tests and organ donation. The tests required are listed in Table 11.9.

| Test | Brainstem function (cranial nerves) |

|---|---|

| Pupil light reflex | II, III |

| Corneal reflex | V, VII |

| Caloric tests | VIII, IV, VI, III |

| Gag reflex | IX, X |

| Tracheal suction | X |

| Response to pain (see text below) | Sensory afferents; motor efferents |

| Apnoea tests | Respiratory centre |

Completion of tests

Following confirmation of brainstem death, arrangements may be made to retrieve organs for transplantation if consent has been obtained. (See Organ donation, p. 437.) Alternatively ventilation may be withdrawn. The family should be offered the opportunity to sit with the patient and allowed time for distant relatives to visit. At the time of ventilator disconnection they may choose to stay with the patient. Alternatively, some prefer to say their farewells before the event and leave or visit later.

NEUROMUSCULAR CONDITIONS

Autonomic neuropathy leading to cardiovascular instability. Bradycardias, tachycardias, hypertension or hypotension may all occur.

Autonomic neuropathy leading to cardiovascular instability. Bradycardias, tachycardias, hypertension or hypotension may all occur. Marked sensitivity to muscle relaxants. There may be long lasting weakness after non-depolarizing drugs. Massive K+ release after suxamethonium is well recognized even before clinical manifestations are seen, and is thought to be caused by extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors. Avoid using it!

Marked sensitivity to muscle relaxants. There may be long lasting weakness after non-depolarizing drugs. Massive K+ release after suxamethonium is well recognized even before clinical manifestations are seen, and is thought to be caused by extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors. Avoid using it!Myasthenia gravis

Deterioration, increasing muscle weakness and subsequent respiratory failure may result from intercurrent disease, surgery or overdosage of anticholinesterase drugs (cholinergic crisis). The short-acting anticholinesterase edrophonium may be given to test whether muscle function can be improved (‘Tensilon test’). In practice, by the time myasthenic patients require intensive care it is often difficult to distinguish a cholinergic crisis from other causes of muscle fatigue.

Botulism

This is rare in the UK but occasional outbreaks have been associated with contaminated packaged food. Toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum blocks cholinergic receptors. Nausea and vomiting are followed by blurred vision, laryngeal and pharyngeal paralysis and generalized paralysis. Tachycardia, urinary retention and constipation occur. Treatment is largely supportive. Seek specialist advice.

Suxamethonium causes a transient rise in intracranial pressure. However, in the context of the multiply-injured patient with brain injury, securing the airway rapidly and safely is essential. Suxamethonium is usually the drug of choice.

Suxamethonium causes a transient rise in intracranial pressure. However, in the context of the multiply-injured patient with brain injury, securing the airway rapidly and safely is essential. Suxamethonium is usually the drug of choice.

Endotracheal and gastric tubes should be inserted via the oral route in the fi rst instance. This is because in the presence of a base-of-skull fracture, there is a risk of these tubes entering the cranium if placed nasally. Only change to nasotracheal / nasogastric tubes once base-of-skull fractures have been excluded.

Endotracheal and gastric tubes should be inserted via the oral route in the fi rst instance. This is because in the presence of a base-of-skull fracture, there is a risk of these tubes entering the cranium if placed nasally. Only change to nasotracheal / nasogastric tubes once base-of-skull fractures have been excluded.

CT scans require skilled interpretation. Do not make clinical decisions until senior experienced staff have reviewed them. Minor subarachnoid bleeding, mild cerebral oedema, early cerebral infarction, pituitary lesions and brainstem lesions are all easily missed.

CT scans require skilled interpretation. Do not make clinical decisions until senior experienced staff have reviewed them. Minor subarachnoid bleeding, mild cerebral oedema, early cerebral infarction, pituitary lesions and brainstem lesions are all easily missed.

If left untreated, patients with DI develop rapid and progressive dehydration and hypernatraemia. Avoid rapid correction, which may lead to acute cerebral oedema. (See Hypernatraemia, p. 202.)

If left untreated, patients with DI develop rapid and progressive dehydration and hypernatraemia. Avoid rapid correction, which may lead to acute cerebral oedema. (See Hypernatraemia, p. 202.) Jugular bulb lactate–oxygen index, may be helpful in distinguishing critically perfused brain. LOi = AVDL / AVDO2 (AV difference in lactate / AV difference in oxygen content.) If this is used in your unit, seek advice on calculation and interpretation.

Jugular bulb lactate–oxygen index, may be helpful in distinguishing critically perfused brain. LOi = AVDL / AVDO2 (AV difference in lactate / AV difference in oxygen content.) If this is used in your unit, seek advice on calculation and interpretation.

The preconditions for the diagnosis of brainstem death are absolutely fundamental to the process and must be satisfied before consideration of the diagnosis.

The preconditions for the diagnosis of brainstem death are absolutely fundamental to the process and must be satisfied before consideration of the diagnosis. Do not use the terms pass or fail in relation to brainstem death tests. This creates confusion. Brainstem death is either confirmed or not confirmed.

Do not use the terms pass or fail in relation to brainstem death tests. This creates confusion. Brainstem death is either confirmed or not confirmed.

Patients with neuromuscular disease may be profoundly weak but usually retain a normal conscious level. If ventilator-dependent, they may be unable to move or show any sign of distress. (The only means of communication may be by blinking the eyelids.) It should be assumed that they are conscious until proved otherwise. Ensure adequate levels of sedation / analgesia.

Patients with neuromuscular disease may be profoundly weak but usually retain a normal conscious level. If ventilator-dependent, they may be unable to move or show any sign of distress. (The only means of communication may be by blinking the eyelids.) It should be assumed that they are conscious until proved otherwise. Ensure adequate levels of sedation / analgesia. Occasional cases of tetanus and botulism have been seen in recent years, in association with drug abuse, in particular, by drug abusers who self inject, using intramuscular, subcutaneous, or “skin popping” techniques, rather than intravenous injection. Treatment is as above. (See Problems associated with intravenous drug abuse, p. 243).

Occasional cases of tetanus and botulism have been seen in recent years, in association with drug abuse, in particular, by drug abusers who self inject, using intramuscular, subcutaneous, or “skin popping” techniques, rather than intravenous injection. Treatment is as above. (See Problems associated with intravenous drug abuse, p. 243).