Chapter 18 Brachial Plexus

Overview of the Brachial Plexus

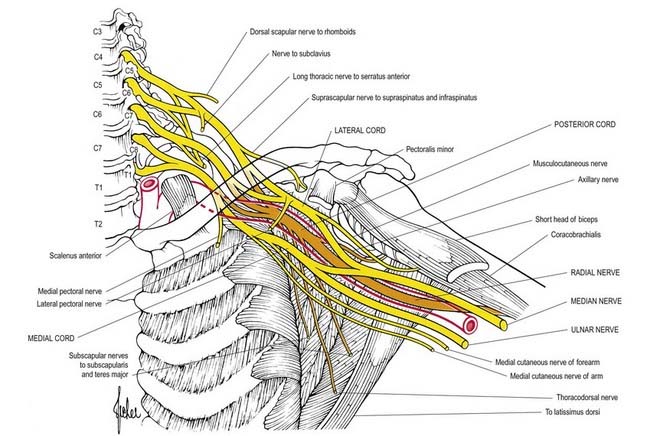

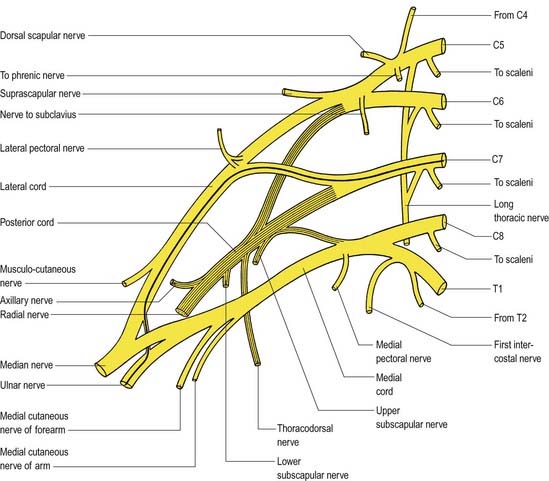

The brachial plexus is a union of the ventral rami of the lower four cervical nerves and the greater part of the first thoracic ventral ramus (Figs 18.1, 18.2). The fourth ramus usually gives a branch to the fifth, and the first thoracic frequently receives one from the second. These ventral rami are the roots of the plexus; they are almost equal in size but variable in their mode of junction. Contributions to the plexus by C4 and T2 vary. When the branch from C4 is large, that from T2 is frequently absent and the branch from T1 is reduced, forming a ‘prefixed’ type of plexus. If the branch from C4 is small or absent, the contribution from C5 is reduced, that from T1 is larger and there is always a contribution from T2; this arrangement constitutes a ‘postfixed’ type of plexus.

Fig. 18.1 Plan of the brachial plexus. The posterior division of the trunks and their derivatives are shaded; the fibres from C7 that enter the ulnar nerve are shown as a heavy black line. C4 to C8 and T1 and T2 indicate the ventral rami of these cervical and thoracic spinal nerves.

Overview of the Principal Nerves

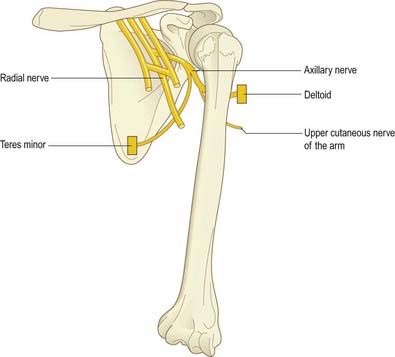

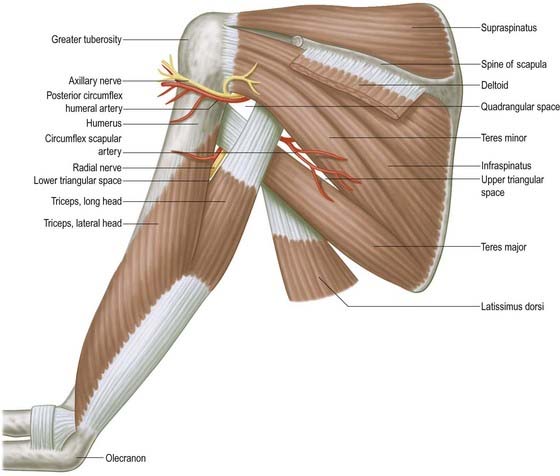

Axillary Nerve (C5, C6)

The axillary nerve is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It winds posteriorly around the neck of the humerus together with the circumflex humeral vessels and supplies the deltoid and teres minor and an area of skin over the deltoid region (Fig. 18.3).

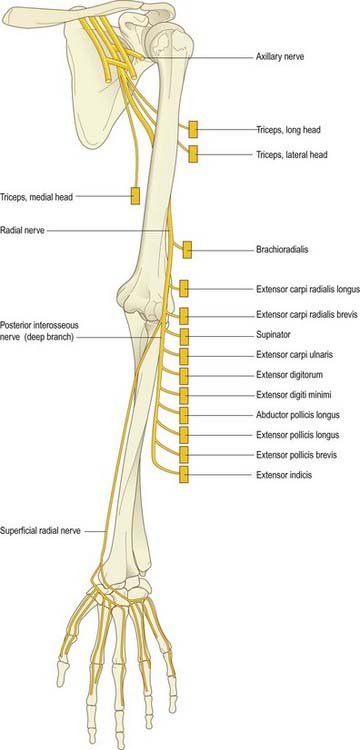

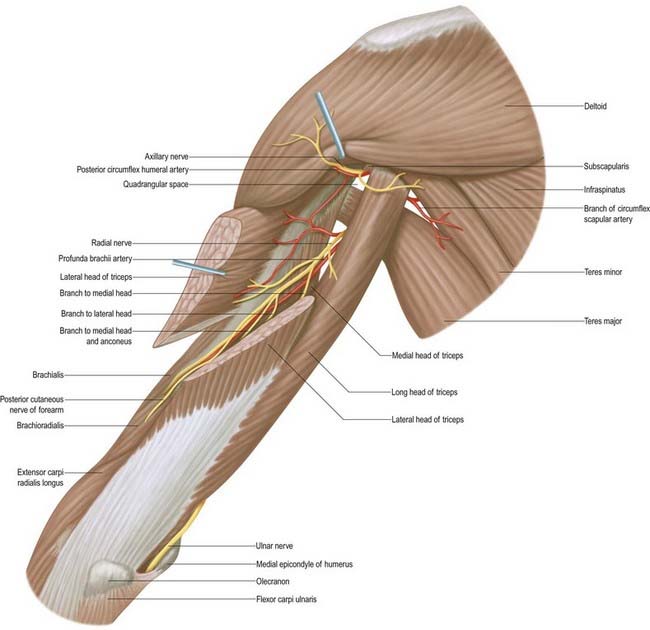

Radial Nerve (C5–8, T1)

The radial nerve is the continuation of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (Fig. 18.4). In the upper arm it lies in the spiral groove of the humerus, where it is accompanied by the profunda brachii artery and its venae comitantes. It enters the posterior (extensor) compartment and supplies triceps, then reenters the anterior compartment of the arm by piercing the lateral intermuscular septum. At the level of the lateral epicondyle it gives off the posterior interosseous nerve, which passes between the two heads of the supinator and enters the extensor compartment of the forearm. The posterior interosseous nerve supplies these muscles. The radial nerve itself continues into the forearm in the anterior compartment deep to the brachioradialis. It terminates by supplying the skin over the posterior aspect of the thumb, index, middle fingers and radial half of the ring finger.

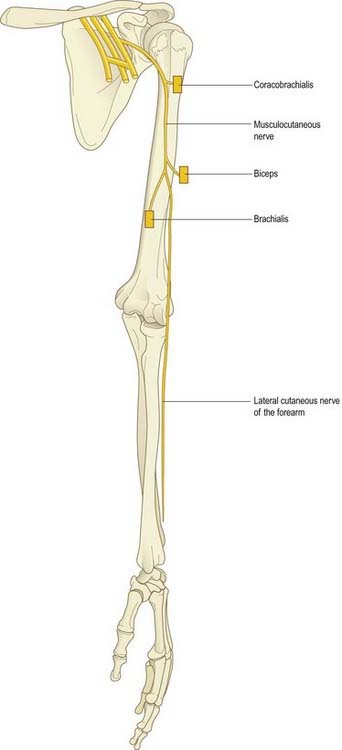

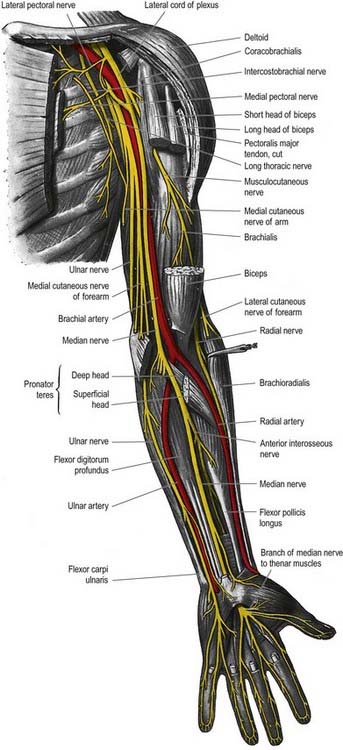

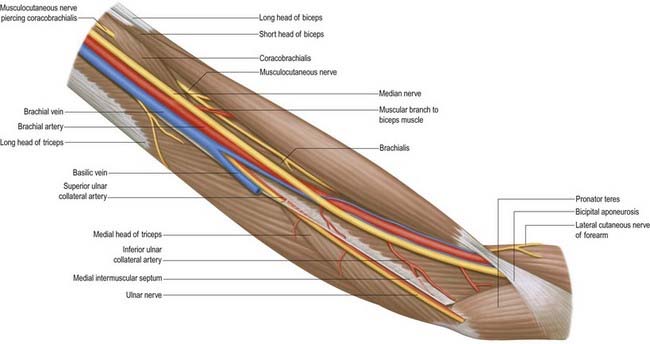

Musculocutaneous Nerve (C5–7)

The musculocutaneous nerve is formed from the continuation of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. It pierces the coracobrachialis; supplies it, biceps and brachialis; then continues into the forearm as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (Fig. 18.5).

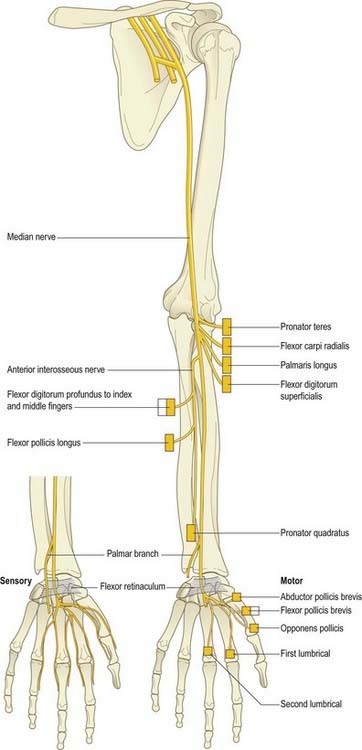

Median Nerve (C6–8, T1)

The median nerve is formed by the union of the terminal branch of the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (Fig. 18.6). It has no branches in the upper arm. It enters the forearm between the two heads of pronator teres and gives off the anterior interosseous nerve, which supplies all the flexor muscles of the forearm except for flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar half of flexor digitorum profundus. The median nerve itself passes deep to the flexor retinaculum at the wrist. On entering the palm, it gives off motor branches to the thenar muscles and the radial two lumbricals and cutaneous branches to the palmar aspect of the thumb, index and middle fingers and the radial half of the ring finger.

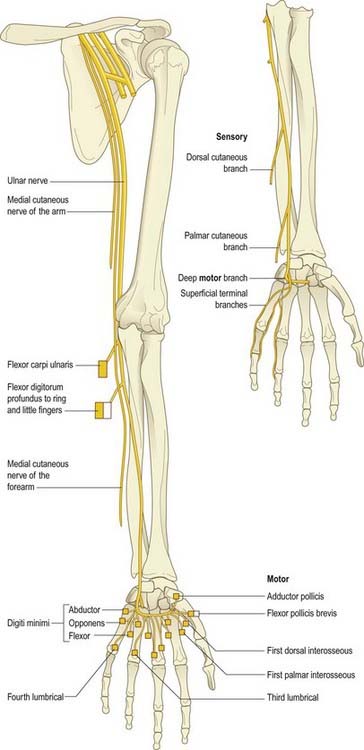

Ulnar Nerve (C7, C8, T1)

The ulnar nerve is the continuation of the medial cord of the brachial plexus (Fig. 18.7). Like the median nerve, it has no branches in the upper arm. It enters the posterior compartment of the upper arm midway down its length by piercing the medial intermuscular septum and passes behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus to enter the forearm. It passes to the wrist deep to flexor carpi ulnaris, giving branches to this muscle and to the ulnar half of flexor digitorum profundus. Just proximal to the wrist it gives off a dorsal cutaneous branch that supplies the skin over the dorsal aspect of the little finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger. The ulnar nerve crosses into the palm superficial to the flexor retinaculum in Guyon’s canal. It divides into a motor branch, which supplies the hypothenar muscles, the intrinsics (apart from the radial two lumbricals) and adductor pollicis, and cutaneous branches, which supply the skin of the palmar aspect of the little finger and ulnar half of the ring finger.

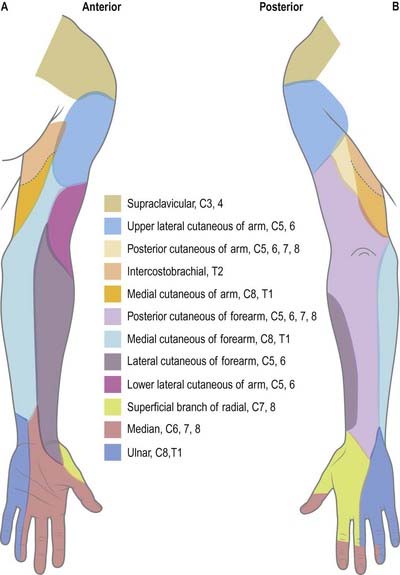

Dermatomes

Our knowledge of the extent of individual dermatomes, especially in the limbs, is based largely on clinical evidence (Fig. 18.8). The dermatomes of the upper limb arise from spinal nerves C5–8 and T1. C7 supplies the central part of the hand. Considerable overlap exists between adjacent dermatomes innervated by nerves derived from consecutive spinal cord segments.

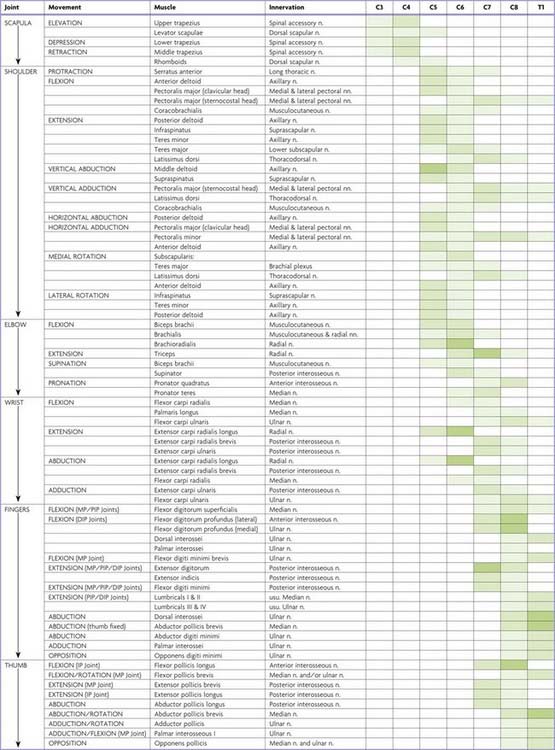

Myotomes

Each spinal nerve originally supplies the musculature derived from its own myotome. Where myotomal derivatives remain entities, they retain their original segmental supply. When derivatives from adjoining myotomes fuse, the resulting muscles do not always retain a nerve supply from each corresponding spinal nerve. Because muscles develop in situ, in the mesodermal cores of the developing limbs, it is impossible to identify their original segments by a developmental study. Most limb muscles are innervated by neurones from more than one segment of the spinal cord. Tables 18.1 to 18.4 summarize the predominant segmental origins of the nerve supply for each of the upper limb muscles and for movements taking place at the joints of the upper limb; damage to these segments or to their motor roots results in maximal paralysis.

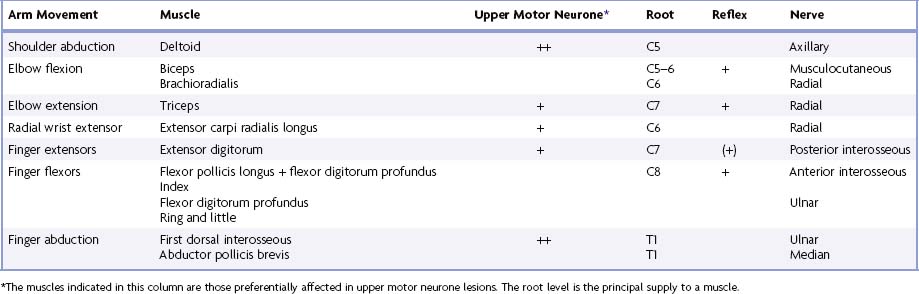

Table 18.1 Movements, muscles and segmental innervation in the upper limb

Table 18.2 Segmental innervation of muscles of the upper limb

| C3, C4 | Trapezius, levator scapulae |

| C5 | Rhomboids, deltoids, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, biceps |

| C6 | Serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis, teres major, pectoralis major (clavicular head), biceps, coracobrachialis, brachialis, brachioradialis, supinator, extensor carpi radialis longus |

| C7 | Serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major (sternal head), pectoralis minor, triceps, pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi |

| C8 | Pectoralis major (sternal head), pectoralis minor, triceps, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor indicis, abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis |

| T1 | Flexor digitorum profundus, intrinsic muscles of the hand (except abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis) |

Table 18.3 Segmental innervation of joint movements of the upper limb

| Shoulder | Abductors and lateral rotators | C5 |

| Abductors and medial rotators | C6–8 | |

| Elbow | Flexors | C5, C6 |

| Extensors | C7, C8 | |

| Forearm | Supinators | C6 |

| Pronators | C7, C8 | |

| Wrist | Flexors and extensors | C6, C7 |

| Digits | Long flexors and extensors | C7, C8 |

| Hand | Intrinsic muscles | C8, T1 |

Muscle Innvervation and Function

Table 18.1 provides the following information about the innervation and functions of muscles in the upper limb:

Movements

At the central nervous level of control, muscles are recognized not as individual actuators but as components of movement. Muscles may contribute to several types of movement, acting variously as prime movers, antagonists, fixators or synergists. For example, in the movement of the scapula around the thorax, serratus anterior acts as an antagonist of trapezius, but in the forward rotation of the scapula, the two muscles combine as prime movers. Moreover, a muscle that crosses two joints can produce more than one movement. Even a muscle that acts across one joint can produce a combination of movements, such as flexion with medial rotation or extension with adduction. Some muscles have therefore been included in more than one place in Table 18.1, but even these listings are not exhaustive.

Nerve Roots

The spinal roots listed as contributing to muscle innervation vary in different texts; this is a reflection of the often unreliable nature of available information. The most positive identifications have been obtained by electrically stimulating spinal roots and recording the evoked electromyographic activity in the muscles. This is a laborious process, however, and data of this quality are in limited supply. Much of the information in Table 18.1 is based on neurological experience gained in examining the effects of lesions, and some of it is far from new.

Major and Minor Contributions

Spinal roots have been given the same shading in Table 18.1 when they innervate a muscle to a similar extent or when differences in their contribution have not been described. Heavy shading indicates roots from which there is known to be a dominant contribution. From a clinical viewpoint, some of these roots may be regarded as innervating the muscle almost exclusively: for example, deltoid by C5, brachioradialis by C6, triceps by C7. Minor contributions have been retained in the table to increase its utility in other contexts, such as electromyography and comparative anatomy.

Clinical Testing

For diagnostic purposes, it is neither necessary nor possible to test every muscle, and the experienced neurologist can cover every clinical possibility with a much shorter list. In Table 18.1, red has been used to highlight those muscles or movements that have diagnostic value. The emphasis here is on the differentiation of lesions at different root levels. Other lists could be developed to differentiate between lesions at the level of the root, plexus or peripheral nerve; at different sites along the length of a nerve; or between different peripheral nerves. The preferred criteria for including a given muscle in such a list are that it is visible and palpable, that its action is isolated or can be isolated by the examiner, that it is innervated by one peripheral nerve or (predominantly) one root, that it has a clinically elicitable reflex and that it is useful in differentiating among different nerves, roots or lesion levels.

Determination of A Lesion’s Location

Any muscle to be tested must satisfy a number of criteria. It should be visible, so that wasting or fasciculation can be observed and the muscle’s consistency with contraction can be felt. It should have an isolated action, so that its function can be tested separately. The muscle tested should help differentiate between lesions at different levels in the neuraxis and in peripheral nerves, or between peripheral nerves. It should be tested in such a way that normal can be differentiated from abnormal, so that slight weakness can be detected early with reliability. Some preference should be given to muscles with an easily elicited reflex.

Table 18.4 lists movements and muscles chosen according to these criteria. For example, with an upper motor neurone lesion, shoulder abduction, elbow extension, wrist and finger extension and finger abduction are weaker than their opposing movements. Because this weakness may be more distal than proximal, or vice versa, normal shoulder abduction and finger abduction excludes an upper motor neurone weakness of the arm. Some muscles are difficult to test but are included for special reasons. For example, brachioradialis strength is difficult to assess, but the muscle can be seen and felt, it is innervated mostly by the C6 root, and it has an easily elicited reflex.

Brachial Plexus and Nerves of the Shoulder

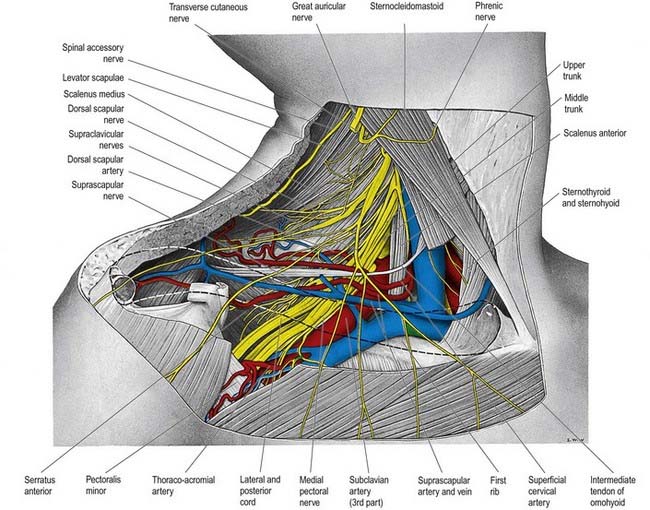

In the axilla, the lateral and posterior cords of the brachial plexus are lateral to the first part of the axillary artery, and the medial cord is behind it. The cords surround the second part of the artery; their names indicate their relationship. In the lower axillae the cords divide into nerves that supply the upper limb (see Fig. 18.2). Except for the medial root of the median nerve, these nerves are related to the third part of the artery, and their cords are related to the second part; that is, branches of the lateral cord are lateral, branches of the medial cord are medial, and branches of the posterior cord are posterior to the artery.

Branches of the brachial plexus may be described as supraclavicular or infraclavicular.

Supraclavicular Branches

| From roots | 1. Nerves to scaleni and longus colli | C5, C6, C7, C8 |

| 2. Branch to phrenic nerve | C5 | |

| 3. Dorsal scapular nerve | C5 | |

| 4. Long thoracic nerves | C5, C6 (C7) | |

| From trunks | 1. Nerve to subclavius | C5, C6 |

| 2. Suprascapular nerve | C5, C6 |

Long Thoracic Nerve

The long thoracic nerve is usually formed by roots from the fifth to seventh cervical rami, although the last ramus may be absent (Fig. 18.9). The upper two roots pierce scalenus medius obliquely, uniting in or lateral to it. The nerve descends dorsal to the brachial plexus and the first part of the axillary artery and crosses the superior border of serratus anterior to reach its lateral surface. It may be joined by the root from C7, which emerges between scalenus anterior and scalenus medius, and descends on the lateral surface of medius. The nerve continues downward to the lower border of serratus anterior and supplies branches to each of its digitations.

The long thoracic nerve is the most common nerve to be affected by neuralgic amyotrophy. Winging of the scapula may be the only clinical manifestation; it is best demonstrated by asking the patient to push against resistance with the arm extended at the elbow and flexed to 90° at the shoulder (Fig. 18.10; see Case 1).

Suprascapular Nerve

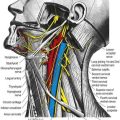

The suprascapular nerve is a large branch of the superior trunk (Fig. 18.11). It runs laterally, deep to trapezius and omohyoid, and enters the supraspinous fossa through the suprascapular notch inferior to the superior transverse scapular ligament. It runs deep to supraspinatus and curves around the lateral border of the spine of the scapula with the suprascapular artery to reach the infraspinous fossa, where it gives two branches to supraspinatus and articular rami to the shoulder and acromioclavicular joints. The suprascapular nerve rarely has a cutaneous branch. When present, it pierces the deltoid close to the tip of the acromion and supplies the skin of the proximal third of the arm within the territory of the axillary nerve.

Fig. 18.11 Lower part of the posterior triangle showing the relations of the third part of the right subclavian artery. The clavicle has been removed, but its outline is indicated by a dashed line. In this dissection, the middle trunk of the brachial plexus gives an unusual contribution to the medial cord.

Infraclavicular Branches

| Lateral cord | Lateral pectoral | C5, C6, C7 |

| Musculocutaneous | C5, C6, C7 | |

| Lateral root of median | (C5), C6, C7 | |

| Medial cord | Medial pectoral | C8, T1 |

| Medial cutaneous of forearm | C8, T1 | |

| Medial cutaneous of arm | C8, T1 | |

| Ulnar | (C7), C8, T1 | |

| Medial root of median | C8, T1 | |

| Posterior cord | Upper subscapular | C5, C6 |

| Thoracodorsal | C6, C7, C8 | |

| Lower subscapular | C5, C6 | |

| Axillary | C5, C6 | |

| Radial | C5, C6, C7, C8, (T1) |

Lateral Pectoral Nerve

The lateral pectoral nerve (see Fig. 18.9) is larger than the medial and may arise from the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks or by a single root from the lateral cord. Its axons are from the fifth to seventh cervical rami. It crosses anterior to the axillary artery and vein, pierces the clavipectoral fascia and supplies the deep surface of pectoralis major. It sends a branch to the medial pectoral nerve, forming a loop in front of the first part of the axillary artery (see Fig. 18.9), to supply some fibres to pectoralis minor.

Axillary Nerve

The axillary nerve arises from the posterior cord (C5, C6). It is initially lateral to the radial nerve, posterior to the axillary artery and anterior to subscapularis (Fig. 18.12). At the lower border of subscapularis it curves back inferior to the humeroscapular articular capsule and, with the posterior circumflex humeral vessels, traverses a quadrangular space bounded above by subscapularis (anterior) and teres minor (posterior), below by teres major, medially by the long head of triceps and laterally by the surgical neck of the humerus. In the space it divides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch curves around the neck of the humerus with the posterior circumflex humeral vessels, deep to deltoid. It reaches the anterior border of the muscle, supplies it and gives off a few small cutaneous branches that pierce deltoid and ramify in the skin over its lower part. The posterior branch courses medially and posteriorly along the attachment of the lateral head of triceps, inferior to the glenoid rim. It usually lies medial to the anterior branch in the quadrangular space. It gives off the nerve to teres minor and the upper lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm at the lateral edge of the origin of the long head of triceps. The nerve to teres minor enters the muscle on its inferior surface. The posterior branch frequently supplies the posterior aspect of deltoid, usually via a separate branch from the main stem, or occasionally from the superior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm. However, the posterior part of deltoid has a more consistent supply from the anterior branch of the axillary nerve, which should be remembered when performing a posterior deltoid-splitting approach to the shoulder. The upper lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm pierces the deep fascia at the medial border of the posterior aspect of deltoid and supplies the skin over the lower part of deltoid and upper part of the long head of triceps. The posterior branch is intimately related to the inferior aspects of the glenoid and shoulder joint capsule, which may place it at particular risk during capsular plication or thermal shrinkage procedures (Ball et al 2003). There is often an enlargement or pseudoganglion on the branch to teres minor. The axillary trunk supplies a branch to the shoulder joint below subscapularis.

Musculocutaneous Nerve

The musculocutaneous nerve (see Fig. 18.9) arises from the lateral cord (C5–7), opposite the lower border of pectoralis minor. It pierces coracobrachialis and descends laterally between biceps and brachialis to the lateral side of the arm. Just below the elbow it pierces the deep fascia lateral to the biceps tendon and continues as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm. A line drawn from the lateral side of the third part of the axillary artery across coracobrachialis and biceps to the lateral side of the biceps tendon is a surface projection for the nerve (but this varies according to its point of entry into coracobrachialis). It supplies coracobrachialis, both heads of the biceps and most of brachialis. The branch to coracobrachialis is given off before the musculocutaneous nerve enters the muscle; its fibres are from the seventh cervical ramus and may branch directly from the lateral cord. Branches to biceps and brachialis leave after the musculocutaneous has pierced coracobrachialis; the branch to brachialis also supplies the elbow joint. The musculocutaneous nerve supplies a small branch to the humerus, which enters the shaft with the nutrient artery.

Median Nerve

The median nerve has two roots from the lateral (C5, C6, C7) and medial (C8, T1) cords, which embrace the third part of the axillary artery and unite anterior or lateral to it (see Fig. 18.9). Some fibres from C7 leave the lateral root in the lower part of the axilla and pass distomedially posterior to the medial root, and usually anterior to the axillary artery, to join the ulnar nerve. They may branch from the seventh cervical ventral ramus. Clinically, they are believed to be mainly motor and to supply flexor carpi ulnaris. If the lateral root is small, the musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7) connects with the median nerve in the arm. It is described in more detail below.

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve arises from the medial cord (C8, T1) but often receives fibres from the ventral ramus of C7 (see Fig. 18.9). It runs distally through the axilla medial to the axillary artery, between it and the vein. It is described in more detail below.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve is the largest branch of the brachial plexus. It arises from the posterior cord (C5, C6, C7, C8, [T1]; see Fig. 18.12) and descends behind the third part of the axillary artery and the upper part of the brachial artery, anterior to subscapularis and the tendons of latissimus dorsi and teres major. With the arteria profunda brachii it inclines dorsally and passes through the triangular space below the lower border of teres major, between the long head of triceps and the humerus. It is described in more detail below.

Brachial Plexus Lesions

Lower Plexus Palsies

The lower trunk of the brachial plexus (C8, T1), together with the subclavian artery, may be angulated over a cervical rib (thoracic outlet syndrome). Patients may present with vascular symptoms as a result of kinking of the subclavian artery (this is more likely to occur with large bony ribs), or they may present with neurological deficits (this is more likely in patients with small rudimentary ribs that extend into a fibrous band that joins the first rib anteriorly). Cervical ribs are quite common and are rarely associated with symptoms. There is a slow, insidious onset of wasting of the small muscles of the hand, which often starts on the lateral side with involvement of the thenar eminence and first dorsal interosseous. There is pain and paraesthesia in the medial aspect of the forearm, extending to the little finger; this is often aggravated by carrying shopping bags or suitcases. A bruit may be heard over the subclavian artery, and the radial pulse may be easily obliterated by movements of the arm, particularly with the arm extended and abducted at the shoulder.

CASE 2 Pancoast Tumour

A 59-year-old man, a heavy smoker for many years, develops posterior left shoulder pain radiating down the medial aspect of the left arm into the fourth and fifth digits of the hand, with weakness that ultimately involves the entire left hand. He has lost 35 pounds in the past 3 months. Examination demonstrates wasting and weakness of all intrinsic hand muscles on the left, as well as weakness of wrist flexion. There is decreased sensation in the left medial upper arm, forearm and hand, involving especially the fifth digit (Fig. 18.13). He has a mild left Horner’s syndrome, with noticeable ptosis and miosis.

Fig. 18.13 Brachial plexopathy (brachial neuritis). Atrophy of the intrinsic hand muscles due to denervation.

Discussion: Progressive lesions of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus associated with pain in the involved hand and accompanied by a history of weight loss and smoking are most suggestive of a Pancoast tumour, a tumour of the apex of the lung (Fig. 18.14). An enlarging tumour in the apex may erode bone locally and compress the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. Because the C8 and T1 nerve roots form the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, all median- and ulnar-innervated muscles are affected, as is the pectoralis muscle to some extent. Sensory loss appears in the distribution of C8 and T1 dermatomes. Extension of the mass superiorly into the stellate ganglion is responsible for an associated Horner’s syndrome.

Nerves of the Upper Arm and Elbow

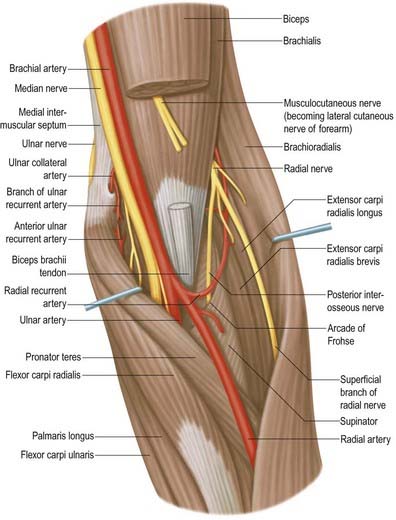

Median Nerve

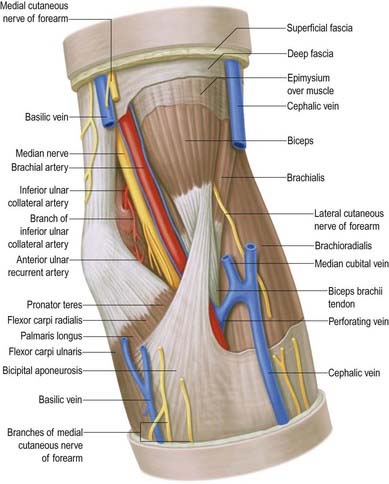

The median nerve enters the arm lateral to the brachial artery (see Fig. 18.9; Figs 18.15, 18.16). Near the insertion of coracobrachialis it crosses in front of (rarely behind) the artery, descending medial to it to the cubital fossa, where it is posterior to the bicipital aponeurosis and anterior to brachialis, separated by the latter from the elbow joint.

Musculocutaneous Nerve

The musculocutaneous nerve is the nerve of the anterior compartment of the arm (see Fig. 18.9). It gives a branch to the shoulder joint and then passes through coracobrachialis, which it supplies, emerging to pass between biceps and brachialis. It sends branches to both these muscles. In the cubital fossa it lies at the lateral margin of the biceps tendon, where it continues as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

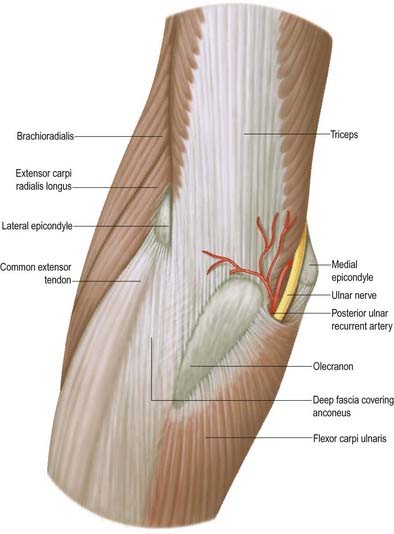

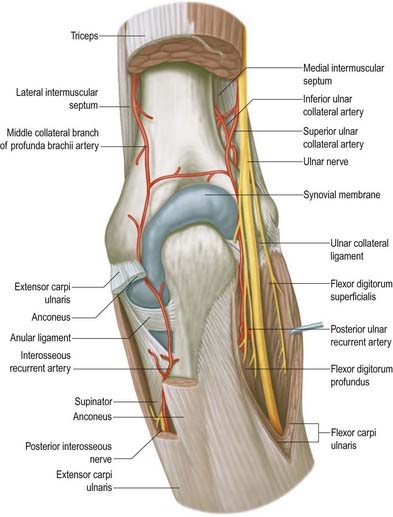

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve has no branches in the arm (see Figs 18.9, 18.15). It runs distally through the axilla medial to the axillary artery and between it and the vein, continuing distally medial to the brachial artery as far as the midarm. There it pierces the medial intermuscular septum, inclining medially as it descends anterior to the medial head of triceps to the interval between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon, along with the superior ulnar collateral artery. At the elbow, the ulnar nerve is in a groove on the dorsum of the epicondyle. It enters the forearm between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris superficial to the posterior and oblique parts of the ulnar collateral ligament (Figs 18.16, 18.17, 18.18).

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Typically, the ulnar nerve can be compressed in the tunnel formed by the tendinous arch connecting the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris at their humeral and ulnar attachments. Other local causes of compression and neuritis at this site include trauma, compression by the medial head of the triceps, osteophytes, recurrent subluxation of the nerve across the medial epicondyle of the humerus and abnormal muscular variants such as the anconeus epitrochlearis.

Surgical treatment involves decompression of the tunnel by division of the aponeurosis of flexor carpi ulnaris, with or without subsequent anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve descends behind the third part of the axillary artery and the upper part of the brachial artery, anterior to subscapularis and the tendons of latissimus dorsi and teres major (see Fig. 18.9; Fig. 18.19). With the profunda brachii artery it inclines dorsally, passing through the triangular space below the lower border of teres major, between the long head of triceps and the humerus. There it supplies the long head of triceps and gives rise to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm, which supplies the skin along the posterior surface of the upper arm. It then spirals obliquely across the back of the humerus, lying posterior to the uppermost fibres of the medial head of triceps, which separate the nerve from the bone in the first part of the spiral groove. There it gives off a muscular branch to the lateral head of triceps and a branch that passes through the medial head of triceps to anconeus. On reaching the lateral side of the humerus it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum to enter the anterior compartment; it then descends deep in a furrow between brachialis and, proximally, brachioradialis, then, more distally, extensor carpi radialis longus. The radial nerve divides into the superficial terminal branch and the posterior interosseous nerve just anterior to the lateral epicondyle (see Fig. 18.16).

Cutaneous Branches

Cutaneous branches are the posterior and lower lateral cutaneous nerves of the arm and the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm (see Fig. 18.8).

Posterior Cutaneous Nerve of the Arm

The small posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm arises in the axilla and passes medially to supply the skin on the dorsal surface of the arm nearly as far as the olecranon. It crosses posterior to and communicates with the intercostobrachial nerve.

Lesions of the Radial Nerve in the Upper Arm

Lesions of the radial nerve at its origin from the posterior cord in the axilla may be caused by pressure from a long crutch (crutch palsy). Triceps is involved only when lesions occur at this level; it is usually spared in the more common lesions of the radial nerve in the arm because it lies alongside the spiral groove, where the nerve is commonly affected by fractures of the humerus. Compression of the nerve against the humerus occurs if the arm is rested on a sharp edge, such as the back of a chair (see Case 4, ‘Saturday Night Palsy’). Both these injuries cause weakness of brachioradialis, with wasting and loss of the reflex. There is both wristdrop and fingerdrop due to weakness of wrist and finger extensors, as well as weakness of extensor pollicis longus and abductor pollicis longus. There may be sensory impairment or paraesthesia in the distribution of the superficial radial nerve. However, nerve overlap means that usually only a small area of anaesthesia occurs on the dorsum of the hand between the first and second metacarpal bones.

Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Arm

The medial cutaneous nerve of the arm supplies the skin of the medial aspect of the arm (see Figs 18.8, 18.9). It is the smallest branch of the brachial plexus, arises from the medial cord and contains fibres from the eighth cervical and first thoracic ventral rami. It traverses the axilla, crossing anterior or posterior to the axillary vein, to which it is then medial, and communicates with the intercostobrachial nerve; it descends medial to the brachial artery and basilic vein (see Fig. 18.9) to a point midway in the upper arm, where it pierces the deep fascia to supply a medial area in the distal third of the arm, extending to its anterior and posterior aspects. Rami reach the skin anterior to the medial epicondyle and over the olecranon. It connects with the posterior branch of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm. Sometimes the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and the intercostobrachial nerve are connected in a plexiform manner in the axilla. The intercostobrachial nerve may be large and reinforced by part of the lateral cutaneous branch of the third intercostal nerve. It then replaces the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and receives a connection representing the latter from the brachial plexus (occasionally, this connection is absent).

Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

The medial cutaneous nerve of forearm comes from the medial cord (see Fig. 18.9; Fig. 18.20). It is derived from the eighth cervical and first thoracic ventral rami. At first it is between the axillary artery and vein and gives off a ramus that pierces the deep fascia to supply the skin over biceps, almost to the elbow. The nerve descends medial to the brachial artery, pierces the deep fascia with the basilic vein midway in the arm and divides into anterior and posterior branches. The larger, anterior branch usually passes in front of, or occasionally behind, the median cubital vein, descending anteromedially in the forearm to supply the skin as far as the wrist and connecting with the palmar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve. The posterior branch descends obliquely medial to the basilic vein, anterior to the medial epicondyle, and curves around to the back of the forearm, descending on its medial border to the wrist, supplying the skin. It connects with the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm, posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and dorsal branch of the ulnar.

Nerves of the Forearm

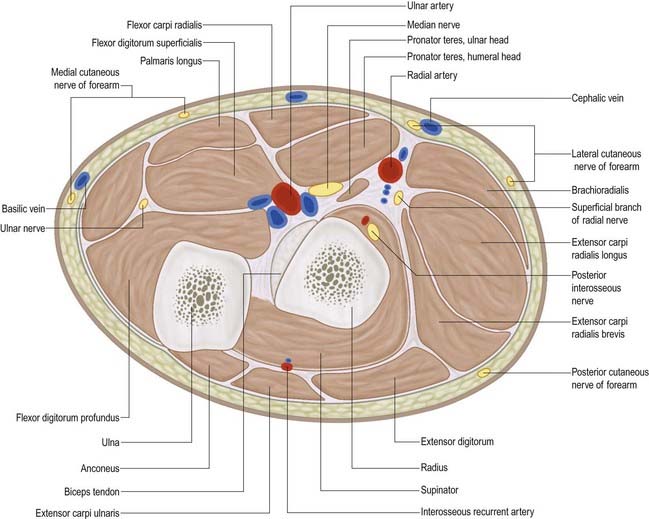

Median Nerve

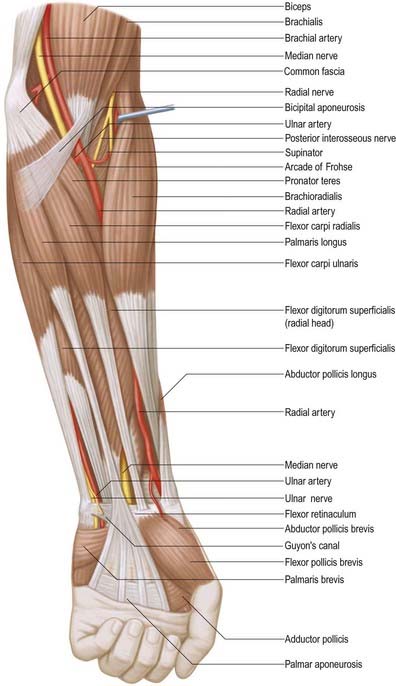

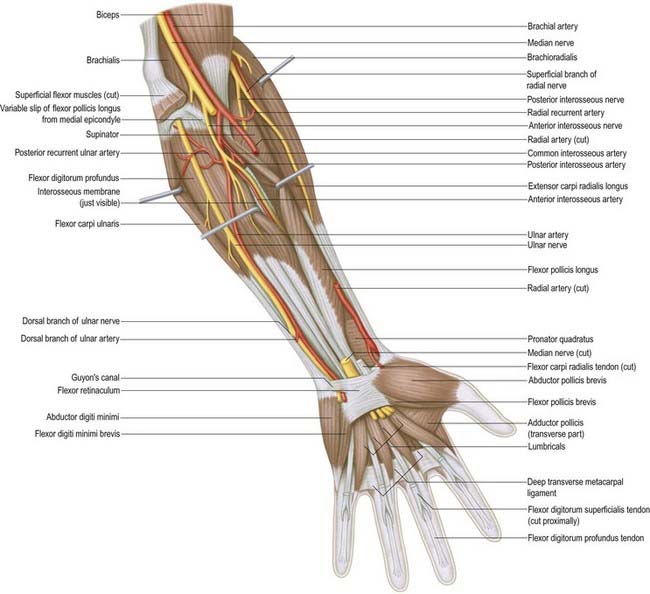

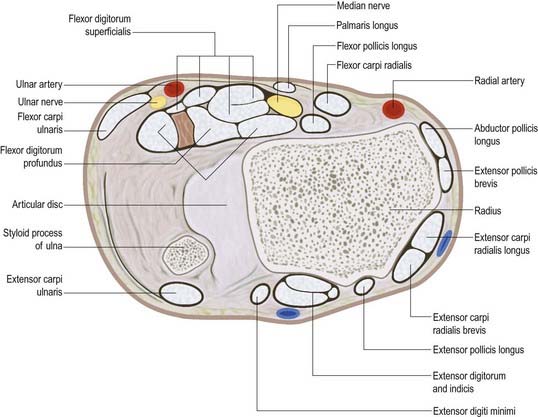

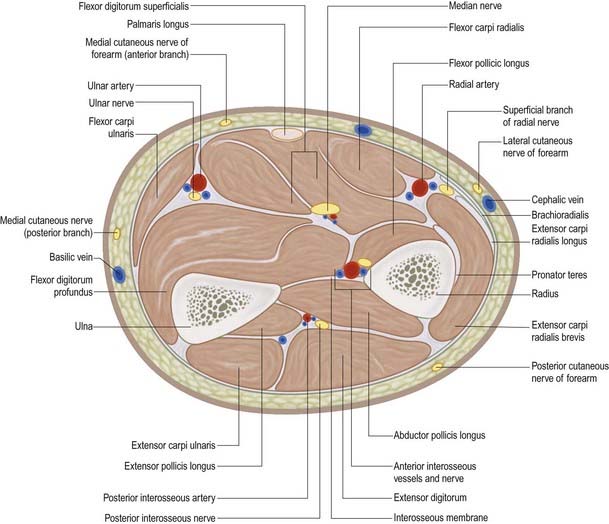

The median nerve usually enters the forearm between the heads of pronator teres (Figs 18.21–18.25). (Occasionally, the nerve passes posterior to both heads of pronator teres, or it may pass through the humeral head.) It crosses to the lateral side of the ulnar artery, from which it is separated by the deep head of pronator teres. It passes behind a tendinous bridge between the humero-ulnar and radial heads of flexor digitorum superficialis, and descends through the forearm posterior and adherent to flexor digitorum superficialis and anterior to flexor digitorum profundus. About 5 cm proximal to the flexor retinaculum it emerges from behind the lateral edge of flexor digitorum superficialis and becomes superficial just proximal to the wrist. There it lies between the tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor carpi radialis, projecting laterally from beneath the tendon of palmaris longus (see Fig. 18.23). It then passes deep to the flexor retinaculum into the palm. In the forearm the median nerve is accompanied by the median branch of the anterior interosseous artery.

Fig. 18.24 Transverse section through the left forearm at the level of the radial tuberosity (proximal aspect).

The course and distribution of the median nerve in the wrist and hand are described below.

Martin–Gruber Connection

Multiple communicating branches between the median nerve (and sometimes the anterior interosseous nerve) arise proximally and pass medially between flexors digitorum superficialis and profundus, deep to the ulnar artery, and join the ulnar nerve. This motor fibre communication (commonly referred to as the Martin–Gruber connection) is estimated to be present in 17% of individuals. It results in median nerve innervation of a variable number of intrinsic muscles of the hand (Leibovic and Hastings 1992) and presumably explains why isolated ulnar and median nerve lesions can be unpredictable in terms of the pattern of intrinsic muscle paralysis.

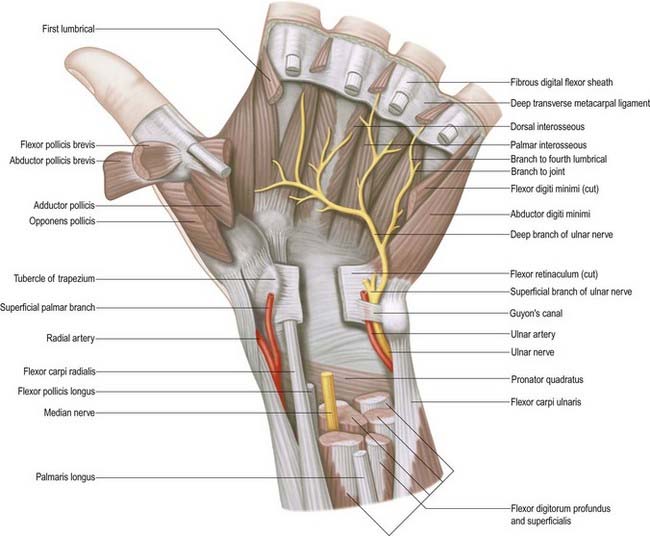

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve descends on the medial side of the forearm, lying on flexor digitorum profundus (see Figs 18.22–18.25). Proximally, it is covered by flexor carpi ulnaris; its distal half lies lateral to the muscle and is covered only by skin and fasciae. In the upper third of the forearm, the nerve is distant from the ulnar artery, but more distally, it comes to lie close to the medial side of the artery. About 5 cm proximal to the wrist it gives off a dorsal branch that continues distally into the hand, anterior to the flexor retinaculum on the lateral side of the pisiform and posteromedial to the ulnar artery. It passes deep to the superficial part of the retinaculum (in Guyon’s canal) with the artery and divides into superficial and deep terminal branches.

The course and distribution of the ulnar nerve in the hand are described below.

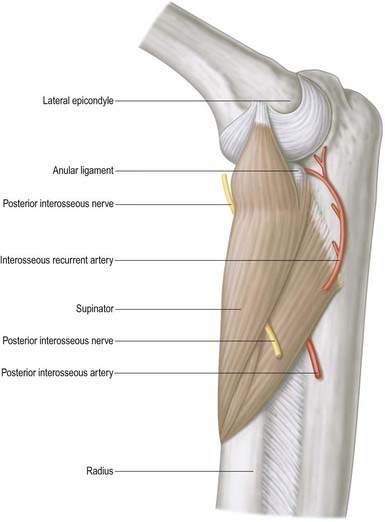

Radial Nerve

There is some variation in the level at which branches of the radial nerve arise from the main trunk in different subjects (Fig. 18.26; see also Figs 18.23, 18.25). Branches to extensor carpi radialis brevis and supinator may arise from the main trunk of the radial nerve or from the proximal part of the posterior interosseous nerve, but almost invariably above the arcade of Frohse.

Radial Tunnel Syndrome

Radial tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy of the radial nerve near the elbow, where four structures can potentially cause compression of the nerve: (1) fibrous bands (which can tether the radial nerve to the radiohumeral joint), (2) the sharp tendinous medial border of extensor carpi radialis brevis, (3) a leash of vessels from the radial recurrent artery as it passes to supply brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus and (4) the arcade of Frohse, which is the free aponeurotic proximal edge of the superficial part of supinator (see Fig. 18.16).

Superficial Terminal Branch

The superficial terminal branch descends from the lateral epicondyle anterolaterally in the proximal two-thirds of the forearm, initially lying on supinator, lateral to the radial artery and behind brachioradialis. In the middle third of the forearm it lies behind brachioradialis, close to the lateral side of the artery, and is successively anterior to pronator teres, the radial head of flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor pollicis longus. It leaves the artery approximately 7 cm proximal to the wrist and passes deep to the brachioradialis tendon. It curves around the lateral side of the radius as it descends, pierces the deep fascia and divides into five (sometimes four) dorsal digital nerves. On the dorsum of the hand it usually communicates with the posterior and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm.

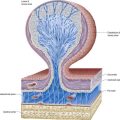

Posterior Interosseous Nerve

The posterior interosseous nerve is the deep terminal branch of the radial nerve (see Fig. 18.24). It reaches the back of the forearm by passing around the lateral aspect of the radius between the two heads of supinator. It supplies extensor carpi radialis brevis and supinator before entering supinator; as it passes through the muscle it supplies it with additional branches. The branch to extensor carpi radialis brevis may arise from the beginning of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. As it emerges from supinator posteriorly, the posterior interosseous nerve gives off three short branches to extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi and extensor carpi ulnaris; it also gives off two longer branches—a medial branch to extensor pollicis longus and extensor indicis, and a lateral branch that supplies abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis. The nerve at first lies between the superficial and deep extensor muscles, but at the distal border of extensor pollicis brevis it passes deep to extensor pollicis longus and, diminished to a fine thread, descends on the interosseous membrane to the dorsum of the carpus. There it presents a flattened and somewhat expanded termination or ‘pseudoganglion,’ from which filaments supply the carpal ligaments and articulations. Articular branches from the posterior interosseous nerve supply carpal, distal radio-ulnar and some intercarpal and intermetacarpal joints. Digital branches supply the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

The medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm has already divided into anterior and posterior branches before it enters the forearm (see Fig. 18.20). The larger anterior branch usually passes in front of, or occasionally behind, the median cubital vein and descends anteromedially in the forearm to supply the skin as far as the wrist. It curves around to the back of the forearm, descending on its medial border to the wrist, supplying the skin. It connects with the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm, posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve.

Lateral Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is a direct continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve as it lies lateral to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa (see Figs 18.5, 18.8). It passes deep to the cephalic vein, descending along the radial border of the forearm to the wrist. It supplies the skin of the anterolateral surface of the forearm and connects with the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and the terminal branch of the radial nerve by branches that pass around its radial border. Its trunk gives rise to a slender recurrent branch that extends along the cephalic vein as far as the middle third of the upper arm, distributing filaments to the skin over the distal third of the anterolateral surface of the upper arm close to the vein. At the wrist joint the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is anterior to the radial artery. Some filaments pierce the deep fascia and accompany the artery to the dorsum of the carpus. The nerve then passes to the base of the thenar eminence, where it ends in cutaneous rami. It has branches that connect with the terminal branch of the radial nerve and the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

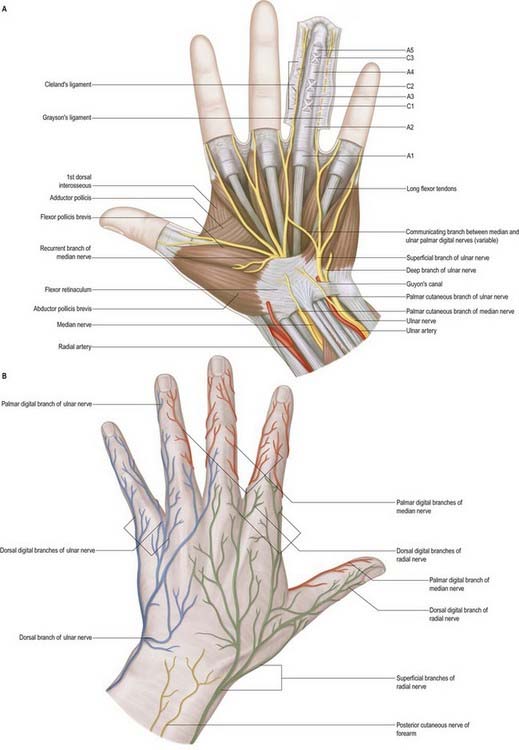

Nerves of the Wrist and Hand

Median Nerve

Muscular Branch (Motor or Recurrent Branch)

The muscular branch is short and thick and arises from the lateral side of the nerve; it may be the first palmar branch or a terminal branch that arises level with the digital branches. It runs laterally, just distal to the flexor retinaculum, with a slight recurrent curve beneath the part of the palmar aponeurosis covering the thenar muscles. It turns around the distal border of the retinaculum to lie superficial to flexor pollicis brevis, which it usually supplies, and continues either superficial to the muscle or traverses it. It gives a branch to abductor pollicis brevis, which enters the medial edge of the muscle and then passes deep to it to supply opponens pollicis, entering its medial edge. Its terminal part occasionally gives a branch to the first dorsal interosseous, which may be its sole or partial supply. The muscular branch may arise in the carpal tunnel and pierce the flexor retinaculum, which is a point of surgical importance.

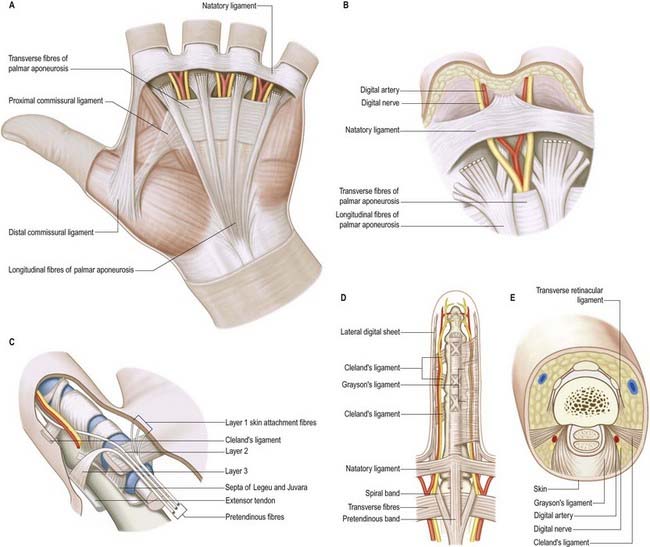

Palmar Digital Branches (Figs 18.27, 18.28)

Fig. 18.27 Cutaneous nerves of the hand. A, Palmar aspect. B, Dorsal aspect. The anular and cruciate pulleys are shown schematically in the ring finger.

The digital nerves supply the fibrous sheaths of the long flexor tendons, digital arteries (vasomotor) and sweat glands (secretomotor). Distal to the base of the distal phalanx, each digital nerve gives off a branch that passes dorsally to the nail bed. The main nerve frequently trifurcates to supply the pulp and skin of the terminal part of the digit. Distal to the base of the proximal phalanx, each proper digital nerve also gives off a dorsal branch to supply the skin over the back of the middle and distal phalanges. The proper palmar digital nerves to the thumb and lateral side of the index finger emerge with the long flexor tendons from under the lateral edge of the palmar aponeurosis. They are arranged in the digits as described earlier, but in the thumb, small distal branches supply the skin on the back of the distal phalanx only.

Other Branches

CASE 6 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

On examination, there is decreased sensation over the thumb, index and middle fingers and half of the ring finger, with sparing of the remainder of the hand, including the thenar eminence. There is mild weakness of abductor pollicis brevis, but strength is otherwise normal (Fig. 18.29). Tapping distal to the proximal (dominant) wrist crease between the tendons of palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis elicits an electric shock–like sensation in the hand (Tinel’s sign). Reflexes are normal.

Ulnar Nerve

Dorsal Branch

The dorsal branch arises approximately 5 cm proximal to the wrist. It passes distally and dorsally, deep to flexor carpi ulnaris; perforates the deep fascia; descends along the medial side of the back of the wrist and hand; and then divides into two, or often three, dorsal digital nerves. The first supplies the medial side of the little finger; the second, the adjacent sides of the little and ring fingers; and the third, when present, supplies adjoining sides of the ring and middle fingers. The last may be replaced, wholly or partially, by a branch of the radial nerve, which always communicates with it on the dorsum of the hand (see Fig. 18.28). In the little finger, the dorsal digital nerves extend only to the base of the distal phalanx; in the ring finger, they extend only to the base of the middle phalanx. The most distal parts of the little finger and of the ulnar side of the ring finger are supplied by dorsal branches of the proper palmar digital branches of the ulnar nerve. The most distal part of the lateral side of the ring finger is supplied by dorsal branches of the proper palmar digital branch of the median nerve.

Deep Terminal Branch

The deep terminal branch accompanies the deep branch of the ulnar artery as it passes between abductor digiti minimi and flexor digiti minimi and then perforates the opponens digiti minimi to follow the deep palmar arch dorsal to the flexor tendons (Fig. 18.30). At its origin, it supplies the three short muscles of the little finger. As it crosses the hand, it supplies the interossei and the third and fourth lumbricals. It ends by supplying adductor pollicis, first palmar interosseous and usually flexor pollicis brevis. It sends articular filaments to the wrist joint.

The medial part of flexor digitorum profundus is supplied by the ulnar nerve, as are the third and fourth lumbricals, which are connected with the tendons of this part of the muscle. Similarly, the lateral part of flexor digitorum profundus and the first and second lumbricals are supplied by the median nerve. The third lumbrical is often supplied by both nerves. The deep terminal branch is thought to give branches to some intercarpal, carpometacarpal and intermetacarpal joints; precise details are uncertain. Vasomotor branches, arising in the forearm and hand, supply the ulnar and palmar arteries.

Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome

Ulnar tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve as it passes through Guyon’s canal at the wrist (see Fig. 18.27). Causes of compression at this site include ganglion, trauma and proximity of aberrant or accessory muscles. Symptoms include pain in the hand or forearm and sensory changes in the palmar aspect of the little finger and ulnar half of the ring finger; however, sensation on the ulnar aspect of the dorsum of the hand is normal. In addition, there may be weakness and wasting of the intrinsic muscles of the hand supplied by the ulnar nerve, with clawing in extreme cases.

Surgical treatment involves decompression of the nerve by division of the roof of Guyon’s canal.

Ulnar Nerve Division at the Wrist

Division of the ulnar nerve at the wrist paralyses all the intrinsic muscles of the hand (except for the radial two lumbricals). The intrinsic muscle action of flexing the metacarpophalangeal joints and extending the interphalangeal joints is therefore lost. The unopposed action of the long extensors and flexors of the fingers causes the hand to assume a clawed appearance with extension of the metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion of the interphalangeal joints. The clawing is less intense in the index and middle fingers because of their intact lumbricals, supplied by the median nerve. For a detailed account of the hand posture adopted in ulnar nerve lesions, see Smith 2002.

Autonomic Innervation

The autonomic supply to the limbs is exclusively sympathetic. The preganglionic sympathetic inflow to the upper limb is derived from neurones in the lateral horn of the upper thoracic spinal segments T2–6 (or 7). Fibres pass in white rami communicantes to the thoracic sympathetic chain and synapse in the stellate and second thoracic ganglia. Postganglionic fibres to the skin are distributed via cutaneous branches of the brachial plexus. The blood vessels to the upper limb receive their sympathetic supply via adjacent peripheral nerves; thus, the median nerve supplies postganglionic sympathetic fibres to the brachial artery and the palmar arches, and the ulnar nerve supplies the ulnar artery.

Special Functions of the Hand

Closing the Hand

Opening the Hand

The tendons of extensor digitorum run distally over the metacarpal heads, forming the major component of the extensor apparatus. Extensor digitorum has no insertion into the proximal phalanx and therefore exerts its extensor action on the metacarpophalangeal joint indirectly through more distal insertions. The first point of insertion is at the base of the middle phalanx (in clinical practice, the term ‘central slip’ has been adopted). Acting at this insertion alone, extensor digitorum can extend both metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints together. The interossei are also active in hand opening because they tend to increase extension of the proximal interphalangeal joint. There is therefore a range of possibilities. At one extreme, with no interosseous contribution, the long extensor exerts all its action at the metacarpophalangeal joint; this leads to full extension or even hyperextension, while the proximal interphalangeal joint remains flexed (the typical claw hand of ulnar nerve paralysis, or ‘intrinsic-minus’ hand). At the other extreme, when the intrinsics act strongly together with extensor digitorum, the proximal interphalangeal joint extends completely while the metacarpophalangeal joint remains flexed (‘intrinsic-plus’ hand). Thus, in the proximal part of the extensor apparatus, the hand possesses a variable mechanism that allows different amounts of relative metacarpophalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joint motion.

One final component of the extensor apparatus provides an additional automatic function. This is a fibrous anchorage system, Landsmeer’s oblique retinacular ligament, which anchors the distal expansion to the middle phalanx. The role of the oblique retinacular ligament is controversial (reviewed by Bendz 1985). Some argue that it may act in a dynamic tenodesis effect to synchronize the movements of the interphalangeal joints; that is, it may initiate extension of the distal interphalangeal joint as the proximal interphalangeal joint is extended from a fully flexed position, and it may relax with proximal interphalangeal joint flexion to allow full distal interphalangeal joint flexion. Others argue that it becomes taut only when the proximal interphalangeal joint is fully extended and the distal interphalangeal joint is flexed, so that it functions as a restraining force to stabilize the fingertip when it is flexed against resistance (e.g. in the hook grip). Another possibility is that the ligament is merely a secondary lateral stabilizer of the proximal interphalangeal joint and that it acts to centralize the extensor components over the dorsum of the middle phalanx.

Movements of the Thumb

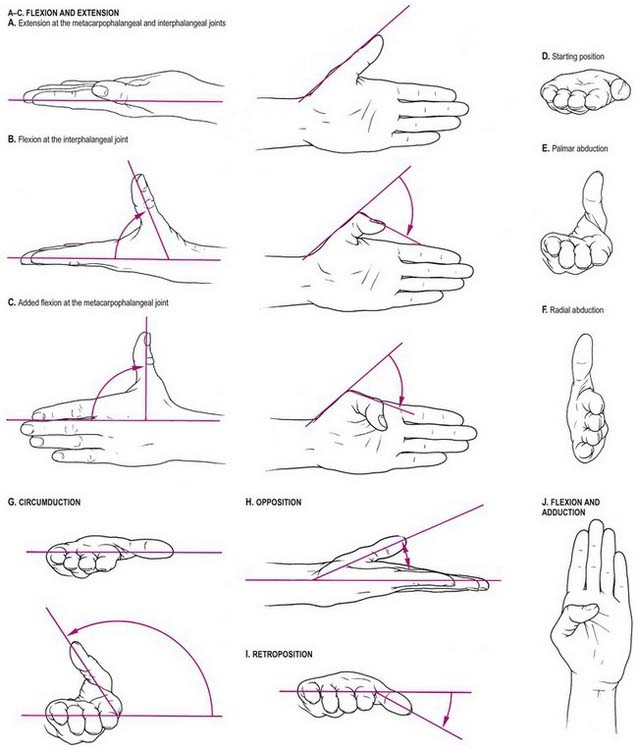

Flexion and extension should be confined to motion at the interphalangeal or metacarpophalangeal joints (Fig. 18.31A–C). Palmar abduction (Fig. 18.31D, E), in which the first metacarpal moves away from the second at right angles to the plane of the palm, and radial abduction (Fig. 18.31D, F), in which the first metacarpal moves away from the second with the thumb in the plane of the palm, occur at the carpometacarpal joint. The opposite of radial abduction is ulnar adduction, or transpalmar adduction, in which the thumb crosses the palm toward its ulnar border. In clinical practice, the term adduction is generally used without qualification. Circumduction describes the angular motion of the first metacarpal, solely at the carpometacarpal joint, from a position of maximal radial abduction in the plane of the palm toward the ulnar border of the hand, maintaining the widest possible angle between the first and second metacarpals (Fig. 18.31G). Lateral inclinations of the first phalanx maximize the extent of excursion of the circumduction arc. Opposition is a composite position of the thumb achieved by circumduction of the first metacarpal, internal rotation of the thumb ray and maximal extension of the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints (Fig. 18.31H). Retroposition is the opposite of opposition (Fig. 18.31I). Flexion adduction is the position of maximal transpalmar adduction of the first metacarpal: the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints are flexed, and the thumb is in contact with the palm (Fig. 18.31J).

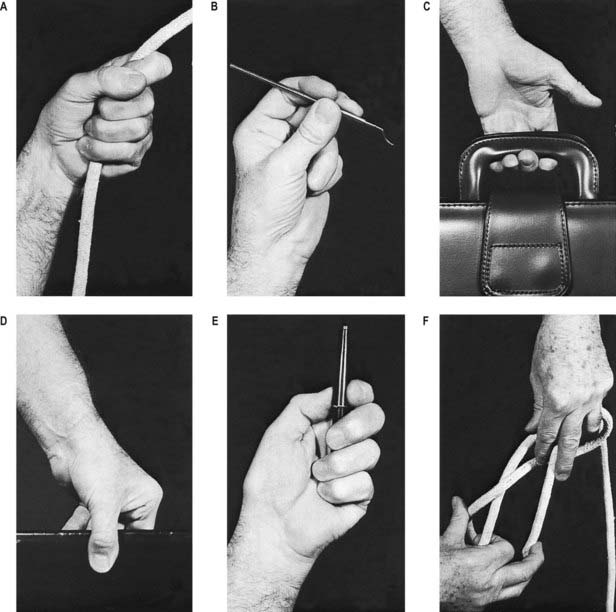

Grips

From different positions of the arc of circumduction, numerous types of pinch grip are possible (Fig. 18.32). In clinical practice, these have been classified into two main types: tip pinch and lateral (or key) pinch. Many forces contribute to these configurations.

The thumb muscles can be classified into those used for retroposition, opposition and pinch grip.

Opposition Muscles

A succession of activity occurs in the thenar muscles during the movement of opposition. Three subgroups of radial (abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis), central (abductor pollicis brevis and opponens pollicis) and ulnar (flexor pollicis brevis) muscles are involved.

Ball C.M., Steger T, Galatz L.M., Yamaguchi K. The posterior branch of the axillary nerve: an anatomic study. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 2003;85:1497-1501.

Bendz P. The functional significance of the oblique retinacular ligament of Landsmeer: a review and new proposals. J. Hand Surg.. 1985;10:25-29.

Leibovic S.J., Hastings H.II. Martin–Gruber revisited. J. Hand Surg.. 1992;17A:47-53.

Smith P.J. Lister’s The Hand: Diagnosis and Indications, fourth ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.