Chapter 4 Botulinum Toxin

Summary

Introduction

Eight neurotoxins are secreted by Clostridium botulinum.1 Type A is a fully sequenced 1295 amino acid chain surrounded by other hemagglutinin and nontoxic nonhemagglutinin proteins for stability.

Dr Alan Scott, an ophthalmologist, pioneered the use of botulinum toxin type A in humans. His first publication, detailing the toxin’s effect on Rhesus monkeys, appeared in 1973.2 He first injected the toxin into humans in 1977 (Scott AB, personal communication). His first publication concerning the injection of the toxin into humans was published in 1980.3

For years, the toxin was an effective, though seldom used medication, limited to the field of investigational ophthalmology. Its primary uses were for blepharospasm and strabismus. There were rare anecdotal reports of its use for wrinkle reduction (Wyshynski PE, personal communication).4 The first comprehensive report detailing its cosmetic usefulness was published by the Carruthers, an ophthalmologist/dermatologist team, in 1992.5

Most patients have an initial excellent response for the first 3.5-4 months, with diminishing returns thereafter as the muscle regains its strength. However, when carefully scrutinized, it typically takes 6-7 months for all of the clinical effects to fade. As patients continue to have the toxin injected on a regular basis over 2 years, most begin to have an increased duration of action.6 Initially, recovery appears to be facilitated by neurite sprouting as early as 8 weeks after injection. It also appears that the initially blocked nerve terminals recover their function.7

Anecdotally, and in one publication,8 it appears that reconstituted toxin that has been allowed to sit unused for weeks may have the same initial effect, but a possibly decreased duration of action.9

Indications

The FDA cosmetic approval for Botox is only for glabellar rhytids in patients under 65 years of age, but I have used it in my practice for patients in their eighties and I have injected every muscle in the face.

Complications from aesthetic surgical procedures

Many complications from aesthetic surgical procedures can be effectively treated with Botox.

Preoperative History and Considerations

Functional anatomy

A classic paper that deals with functional anatomy is Rubin’s description of the different smile patterns from 1974.12 Although all individuals have the same mimetic muscles, their smile patterns are very different depending on which muscles dominate within the group. Even within a single muscle, different portions of that muscle can dominate and severely alter animation. The key is to analyze each patient’s face and discern which portions of which muscles dominate facial activity and cause wrinkles or unaesthetic shaping of the face.

Glabella

Operative Approach

The glabella was the first area to be treated cosmetically with Botox.6 Surgical debulking of the glabellar musculature is an established practice and chemodenervation of these muscles has much the same effect.

Operative technique

Horizontal frowners

Forehead

Operative Approach

Operative technique

Crow’s Feet and Lower Eyelid

Operative Approach

The lateral and inferior orbicularis oculi is weakened to diminish crow’s feet and lower eyelid rhytids in selected patients. The effects of surgically weakening the lateral orbicularis had been known for several years prior to the cosmetic use of Botox injections.14

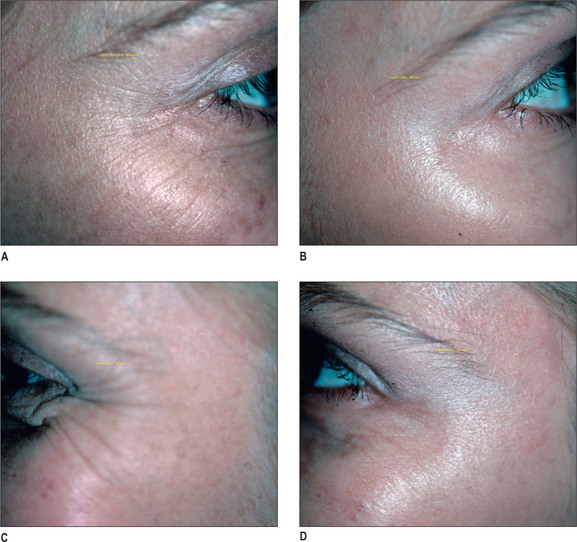

The functional anatomy of this area leads to a classification of crow’s feet patterns.15 The most common pattern is the full fan pattern where the lateral orbicularis contracts and wrinkles the overlying skin from the lateral brow to the lower lid/upper cheek junction, yet even this pattern occurs in less than 50% of patients. The exact incidence of each pattern is not as important as the recognition of different patterns in different patients and asymmetry in individual patients. Treatment is based on the functional anatomy of the orbicularis oculi (Fig. 4.1A-D).

Operative technique

Brow Elevation

Operative Approach

Brow elevation by the injection of Botox was once considered controversial, with publications in both the plastic surgical and dermatologic press saying that Botox could only depress the brows or at best tha it was an illusory brow lift created by dropping the medial brow.

Botox can easily and reliably lift the brows in excess of 6 mm in my practice.

Eleven muscle segments can depress the medial brow:

For a unilateral brow lift (Fig. 4.2A-F), in addition to the zones directly over the brows, weaken the frontalis slightly over the higher brow, inducing the frontalis over the lower brow to pull harder.

Neck

Operative Approach

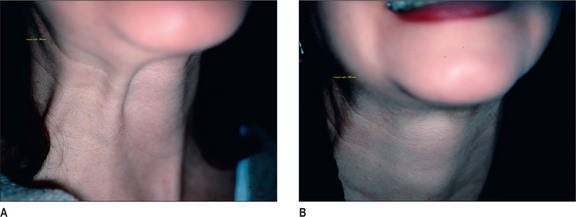

Platysmal bands are another area where Botox injections can yield excellent results. Two articles on neck injection were published simultaneously in 1999 with drastically different dosage, patient populations, results, and complications.16,17 One paper advocated up to 250 units to be injected, had better results in patients with greater skin laxity, and reported dysphagia as a complication.16 I would caution against injecting such high doses in the neck. In addition to dysphagia, high doses can also lead to dry mouth by affecting the salivary glands.

The key to evaluating the neck as a potential site for cosmetic improvement lies in the relative contributions of the skin and the platysma to banding. The best patients have minimal skin excess and relatively strong bands. Despite the results (based on 1500 patients) of the aforementioned paper,16 the patient with lax neck skin is a poor candidate for injection. Even with the bands completely paralyzed, the lax neck skin will continue to hang.

Good candidates for injection fall into two basic categories. The relatively young (35-45 years) patient with strong bands and minimal skin laxity is an excellent patient (Fig. 4.3A&B). Likewise the patient of any age who has had a surgical procedure on the neck and has relatively little excess skin and recurrent bands is a good candidate. A smaller class of patients, but one that is seen more frequently is the young patient who has had an aggressive fat removal procedure in the neck and now has visible bands.

Operative technique

Nasolabial Fold

Operative Approach

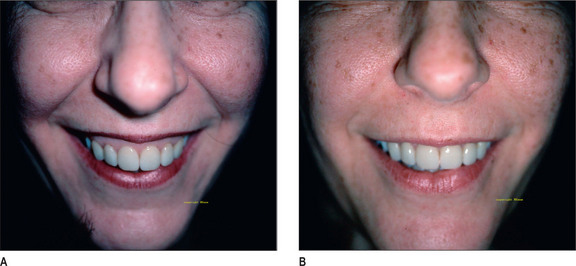

The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle is the muscle mainly responsible for the medial nasolabial fold and the final 3-4 mm of central upper lip elevation.18 Weakening of this muscle smoothes the medial nasolabial fold and changes the smile pattern of the patient.

Rubin described the three major smiling patterns in 1974.

Operative technique

Lower Face

Operative Approach

Perioral rhytids, dimpled chin, and downturned oral commissures are all amenable to improvement by Botox injection.20

Injection of the mentalis is often paired with depressor anguli oris injection to maintain the height of the lower lip (Fig. 4.5A-J).

Complications

Complications may occur from drift of the toxin to adjacent muscles, thereby weakening them. This is especially hazardous when injecting the perioral musculature. Other complications include headache, ecchymosis, and eyelid ptosis.21

Avoiding aspirin and NSAIDs which alter platelet function will reduce ecchymosis. Avoiding too superficial, or dermal, injection will reduce the risk of unaesthetic changes to the skin. Although it does reduce and prevent cystic acne,22 it often leaves the skin overly dry and shiny. Pitfalls to avoid are listed in Box 4.1.

1. Osako M., Keltner J.L. Botulinum A toxin in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1991;36:28-46.

2. Scott A.B., Rosenbaum A., Collins C.C. Pharmacologic weakening of extraocular muscles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1973;12:924-927.

3. Scott A.B. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:1044-1049.

4. Clark R.P., Berris C.E. Botulinum toxin: a treatment for facial asymmetry caused by facial nerve paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:353-355.

5. Carruthers J.D.A., Carruthers J.A. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with Clostridium botulinum A exotoxin. Dermatol Surg. 1992;18:17-21.

6. Kane M.A.C. Muscle atrophy after repeated Botox injections. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Meeting, Los Angeles. May 2, 1998.

7. DePaiva A., Meunier F., Molgo J., et al. Functional repair of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A poisoning: biphasic switch of synaptic activity between nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3200-3205.

8. Hexsel D.M., Almeida A.T.D., et al. Multicenter, double-blind study of the efficacy of injections with botulinum toxin type A reconstituted up to six consecutive weeks before application. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:523-529.

9. Kane M.A.C. Discussion: efficacy of reconstituted and stored botulinum toxin type A: an electrophysiologic and visual study in the auricular muscle of the rabbit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2430.

10. Santo J.L., Swenson P., Glasgow L.A. Potentiation of Clostridium botulinum toxin by aminoglycoside antibiotics: clinical and laboratory observations [Abstract]. Pediatrics. 1981;48:951-955.

11. Brin M.F. Botulinum toxin: chemistry, pharmacology, toxicity, and immunology. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 1997;6:146-168.

12. Rubin L.R. The anatomy of a smile: its importance in the treatment of facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53:384.

13. Rohrich R., Janis J., Fagien S., Stuzin J. The cosmetic use of botulinum toxin CME. Plast Reconst Surg. 2003;112(suppl 5):177-188S.

14. Aston S.J. Orbicularis oculi muscle flaps: a technique to reduce crow’s feet and lateral canthal skin folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:206.

15. Kane M.A.C. Classification of crow’s feet patterns among Caucasian women: the key to individualizing treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(suppl 5):33-39S.

16. Matarasso A., Matarasso S., Brandt F., et al. Botulinum A exotoxin for the management of platysma bands. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:645-652.

17. Kane M.A.C. Nonsurgical treatment of platysmal bands with injection of botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:656-663.

18. Pessa J. Improving the acute nasolabial angle and medial nasolabial fold by levator alae muscle resection. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29:23-30.

19. Kane M.A.C. The effect of botulinum toxin injections on the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(suppl 5):66-72S.

20. Kane M.A.C. The functional anatomy of the lower face as it applies to rejuvenation via chemodenervation. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;21:55-64.

21. Kane M.A.C. Eyelid ptosis following botox injections to the face. American Society of Plastic Surgeons Meeting, Los Angeles. October 13, 2000.