Boston Keratoprosthesis Surgical Technique

Background

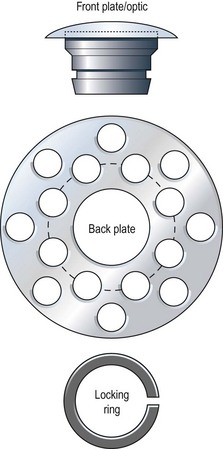

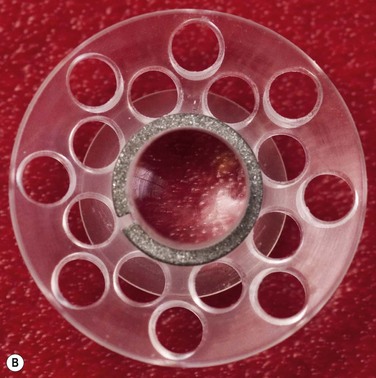

Pellier de Quengsy first proposed the idea of a synthetic or partly synthetic cornea in 1789.1 Dr. Claes Dohlman began development of the Boston keratoprosthesis in 1965; since then, over 7000 have been implanted.2 The Boston keratoprosthesis, when constructed, includes four parts (Fig. 50.1). As configured for implantation, the most anterior component is the optic, which is lathed from a single piece of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) to form the front plate and its stem. A corneal carrier button (allograft or autograft) permits suturing of the device to host cornea and sits between the front plate and the back plate, which is also made of PMMA. Finally, a C-shaped, titanium locking ring encircles the posterior optic stem and prevents disassembly once the keratoprosthesis is implanted in the eye. Incremental improvements in the device since its inception include a snap-in, rather than screw-in, assembly; the addition of back plate perforations to improve nutrition to the corneal carrier and reduce keratolysis; inclusion of the titanium locking ring (Fig. 50.2); and, currently awaiting approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, a change in back plate material from PMMA to titanium.3,4 Other advances include the long-term use of antibiotics and soft contact lenses.5 The Boston keratoprosthesis type I is likely the most commonly implanted artificial cornea worldwide. The Boston keratoprosthesis type II, a modified version of the type I designed to fit through closed eyelids, is used less often.

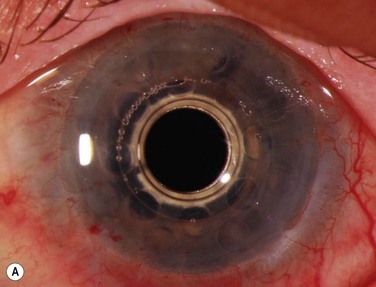

Figure 50.2 (A) An assembled Boston Keratoprosthesis type I with a PMMA back plate, without the donor cornea. (Photo courtesy of Claes H. Dohlman, MD, Ph.D.) (B) Posterior view of an assembled Boston keratoprosthesis type I shows the PMMA back plate with 16 holes and the titanium locking ring.

Once the decision is made to proceed with implantation (see Chapter 49: Keratoprosthesis Indications), a choice must be made whether to implant a type I or type II design. Underlying pathology, as well as completeness of eyelid closure, quality and quantity of preocular tear film, and depth of conjunctival fornices must be determined. The type II device is only utilized in cases of corneal blindness in which damage to the ocular surface and adnexa is extensive enough to make successful retention of the type I device unlikely.6 Candidate patients for a type II keratoprosthesis typically have ocular surface keratinization, severe aqueous tear deficiency, symblephara, and foreshortening of the fornices.7

A detailed preoperative discussion of the risks and benefits of keratoprosthesis implantation is extremely important. Patients must understand that they will need continuous treatment, including daily antibiotics, bandage contact lens wear (for the type I keratoprosthesis), and lifelong follow-up care with a qualified corneal specialist. Long-term follow-up is necessary to maintain patient compliance with medications, recognize and treat indolent infection and early keratolysis, and diagnose new-onset or worsening of pre-existing glaucoma, any of which may compromise the visual gains from the initial surgery and lead to loss of the keratoprosthesis and/or the eye. Patients should also be aware that the cosmetic appearance of the eye will change with keratoprosthesis surgery (Fig. 50.3A), quite notably with the keratoprosthesis type II (Fig. 50.3B). To improve cosmesis following type I keratoprosthesis, some patients choose to wear a painted contact lens. After type II surgery, the cosmetic options are limited to the use of tinted glasses, so patients must receive complete preoperative counseling and be willing to accept this limitation prior to undergoing surgery. For best outcomes in patients with underlying inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis or mucous membrane pemphigoid, attempts should be made to minimize ocular surface inflammation prior to surgery. This may require use of a systemic immunosuppressive agent, such as mycophenolate mofetil. For chronically immunosuppressed patients, collaboration with a rheumatologist, or other similarly qualified physician, is critical to the long-term preservation of the keratoprosthesis.

Preparation of the Boston Keratoprosthesis Type I

The keratoprosthesis is then assembled by positioning the optic with the front plate facing down. This can be done on a manufacturer-provided double-sided adhesive, which secures the prosthesis and thus may make assembly easier. The donor cornea’s 3-mm opening is then positioned over the stem, endothelial side up, and the cornea is lowered over the stem until the epithelial side contacts the back of the front plate. The back plate is then positioned over the stem, with the concave side up, and is pushed down the stem onto the donor cornea using the locking pin. It is unclear whether healthy corneal endothelium is necessary for successful keratoprosthesis implantation,8 but a small amount of viscoelastic may be placed on the endothelial surface to minimize trauma. The prosthesis components are then locked into place by placement of the titanium locking ring over the stem. An audible snap, appreciated with gentle downward pressure by the locking pin, indicates proper positioning of the locking ring, although proper positioning of the device should always be confirmed by careful inspection, under magnification, prior to implantation. The fully assembled keratoprosthesis is then placed in corneal preservation medium and kept covered in a sterile container until needed.

Boston keratoprosthesis Type I Surgery

Once the keratoprosthesis is constructed, the patient’s cornea is removed using a trephine and corneal scissors, as in traditional penetrating keratoplasty, and is sent for pathologic assessment. The iris is inspected through the corneal opening, and, if corectopia resulting in iris obstruction of the visual axis through the keratoprosthesis optic is present, an iridoplasty is performed. If the patient is phakic, cataract extraction must also be performed. The need for placement of a glaucoma drainage implant at the time of surgery (or later) provides rationale for implantation of a posterior chamber intraocular lens, although surgeon preference dictates whether an intraocular lens is placed or the patient is left aphakic. If the patient is pseudophakic, the intraocular lens is stable, and the surgeon has chosen the pseudophakic-powered keratoprosthesis, the intraocular lens is left in place.9

Boston keratoprosthesis Type II Surgery

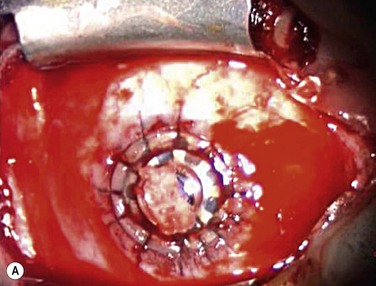

Because implantation of the Boston keratoprosthesis type II requires complete closure of the eyelids, avoidance of encystment requires removal of all ocular surface epithelium. Prior to trephination of the cornea, existing symblephara are divided, and conjunctival mucosal epithelium is removed with sharp dissection, including bulbar, foniceal, and tarsal conjunctiva. The upper and lower eyelid margins are infiltrated with 1% lidocaine containing epinephrine, and the eyelid margins are excised, with care taken to fully excise all eyelash follicles. After the host corneal trephination diameter has been chosen, the cornea is marked with the appropriate trephine, and the limbal and corneal epithelium peripheral to the marked area are removed using sharp dissection. The host cornea is trephined and removed as above. If the eye has not previously undergone intraocular surgery, it may be reasonable to minimize additional procedures inside the eye (although, the crystalline lens must always be removed). However, since most patients receiving a type II keratoprosthesis have had prior surgery, an aggressive approach is recommended in order to prevent postoperative glaucoma. These patients might benefit from total iridectomy, removal of the lens and its capsule, pars plana vitrectomy, and posterior placement of an Ahmed valve. Such additional procedures often require involvement of both a vitreoretinal and a glaucoma surgeon. The prepared keratoprosthesis is typically secured with 12 interrupted 9-0 nylon sutures. Knots are rotated posteriorly but need not be buried. However, as in keratoprosthesis type I surgery, it is important to keep a cover over the anterior keratoprosthesis optic throughout the surgery to prevent light toxicity to the retina (Fig. 50.4A).

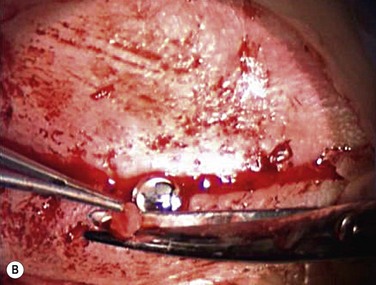

After implantation of the keratoprosthesis, peribulbar antibiotics and corticosteroid are administered as above, and the eyelids are surgically closed around the optic. Two or three interrupted 6-0 Vicryl sutures are placed on each side of the keratoprosthesis (medial and lateral) using partial-thickness tarsal bites. Once the upper and lower tarsi are brought together on either side of the keratoprosthesis stem, the eyelid margins can be gently closed in mattress style with bolsters and 8-0 nylon sutures. Finally, a notch in the upper lid is fashioned with Vannas scissors (Fig. 50.4B) to allow the keratoprosthesis nub to protrude between the eyelids. It is important that this notch be positioned with the eye in primary gaze so that the keratoprosthesis and eyelid opening are properly aligned.

References

1. deQuengsy, GP. Précis au cours d’operations sur la chirurgie des yeux. Paris: Didot; 1789.

2. Klufas, MA, Colby, KA. The Boston keratoprosthesis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:161–175.

3. Khan, BF, Harissi-Dagher, M, Khan, DM, et al. Advances in Boston keratoprosthesis: enhancing retention and prevention of infection and inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:61–71.

4. Todani, A, Ciolino, JB, Ament, JD, et al. Titanium back plate for a PMMA keratoprosthesis: clinical outcomes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1515–1518.

5. Dohlman, CH, Dudenhoefer, EJ, Khan, BF, et al. Protection of the ocular surface after keratoprosthesis surgery: the role of soft contact lenses. CLAO J. 2002;28:72–74.

6. Ciralsky, J, Papaliodis, GN, Foster, CS, et al. Keratoprosthesis in autoimmune disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:275–280.

7. Pujari, S, Siddique, SS, Dohlman, CH, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis type II: the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary experience. Cornea. 2011;30:1298–1303.

8. Robert, MC, Biernacki, K, Harissi-Dagher, M. Boston Keratoprosthesis type 1 surgery: use of frozen versus fresh corneal donor carriers. Cornea. 2012;31:339–345.

9. Utine, CA, Tzu, JH, Dunlap, K, et al. Visual and clinical outcomes of explantation versus preservation of the intraocular lens during Boston type I keratoprosthesis implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1615–1622.