Bones, Joints, and Soft Tissues

The skeletal system provides structural support and protection to the human body and its internal organs, serves as primary home for blood-forming tissues, and stores several vital minerals, above all, calcium. This chapter focuses on alterations of the bony (structural support) part of the skeletal system. Calcium metabolism is also discussed with the endocrine system (chapter 12), and blood-forming tissues are treated separately in the chapter about hematopoietic and lymphatic tissues (chapter 10).

Tumors of the Skeletal System

Tumors of the skeletal system comprise a large variety of benign and malignant lesions, including bone cysts. They are classified according to their tissue of origin and are further identified by the age of the patient and the site. Primary tumors of bone are less common than metastatic lesions to the skeletal system, which always should be considered in differential diagnosis (usually, radiographic findings of primary and metastatic lesions are quite characteristic). The extraskeletal malignant neoplasms most likely to metastasize to the skeleton are carcinomas of the prostate, the breast, the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, the kidneys, and the thyroid. Such metastases may be osteoblastic (e.g., prostate) or osteolytic. Other primary tumors with secondary involvement of the bony skeleton are those of the hematopoietic bone marrow or lymphatic tissues (e.g., plasmacytoma, Hodgkin disease). They are discussed in chapter 10.

Soft Tissue Disorders

TABLE 11-1

PATHOGENETIC FORMS OF OSTEOPOROSIS

| Category | Mechanism | Examples |

| Primary, type 1 | Increased osteoclast activity | Postmenopausal (estrogen withdrawal) |

| Primary, type 2 | Decreased osteoblast activity | “Old age” osteoporosis |

| Secondary | Endocrine disorders | Hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, Cushing syndrome, Addison disease, acromegaly |

| Hematologic diseases | Multiple myeloma, systemic mastocytosis, some leukemias and lymphomas | |

| Malabsorptive | Malabsorption syndromes, malnutrition, gastrectomy, hepatic diseases, vitamin D and C deficiencies | |

| Others | Inactivity osteoporosis, chemotherapy and other drugs, chronic alcoholism, certain metabolic diseases |

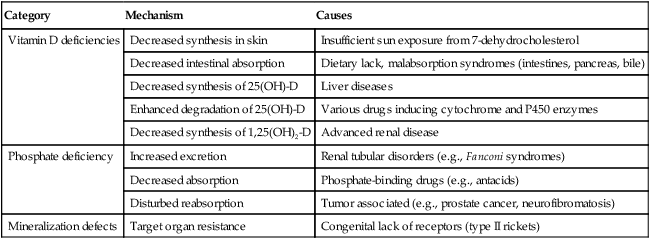

TABLE 11-2

PATHOGENETIC MECHANISMS OF RICKETS AND OSTEOMALACIA*

| Category | Mechanism | Causes |

| Vitamin D deficiencies | Decreased synthesis in skin | Insufficient sun exposure from 7-dehydrocholesterol |

| Decreased intestinal absorption | Dietary lack, malabsorption syndromes (intestines, pancreas, bile) | |

| Decreased synthesis of 25(OH)-D | Liver diseases | |

| Enhanced degradation of 25(OH)-D | Various drugs inducing cytochrome and P450 enzymes | |

| Decreased synthesis of 1,25(OH)2-D | Advanced renal disease | |

| Phosphate deficiency | Increased excretion | Renal tubular disorders (e.g., Fanconi syndromes) |

| Decreased absorption | Phosphate-binding drugs (e.g., antacids) | |

| Disturbed reabsorption | Tumor associated (e.g., prostate cancer, neurofibromatosis) | |

| Mineralization defects | Target organ resistance | Congenital lack of receptors (type II rickets) |

*1,25(OH)-D indicates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D, active form after second hydroxylation in renal tubule; 25(OH)-D, 25-hydroxyvitamin-D, major circulating metabolite hydroxylated in the liver.

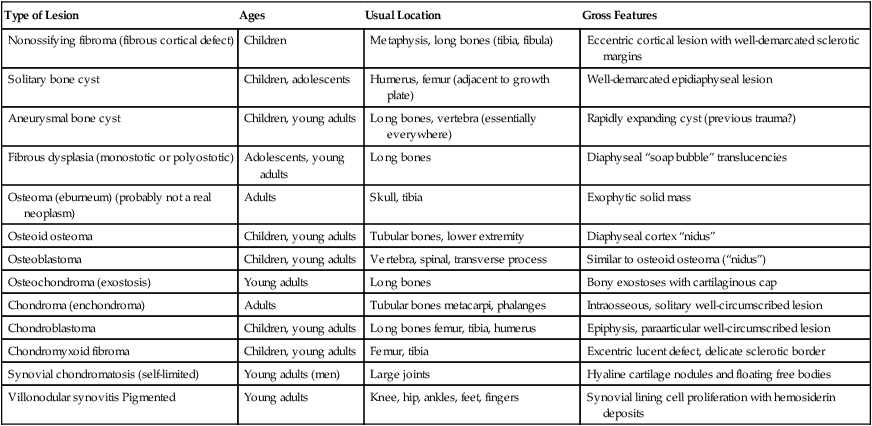

TABLE 11-3

BENIGN PRIMARY TUMOROUS LESIONS OF THE SKELETAL SYSTEM AND JOINTS

| Type of Lesion | Ages | Usual Location | Gross Features |

| Nonossifying fibroma (fibrous cortical defect) | Children | Metaphysis, long bones (tibia, fibula) | Eccentric cortical lesion with well-demarcated sclerotic margins |

| Solitary bone cyst | Children, adolescents | Humerus, femur (adjacent to growth plate) | Well-demarcated epidiaphyseal lesion |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | Children, young adults | Long bones, vertebra (essentially everywhere) | Rapidly expanding cyst (previous trauma?) |

| Fibrous dysplasia (monostotic or polyostotic) | Adolescents, young adults | Long bones | Diaphyseal “soap bubble” translucencies |

| Osteoma (eburneum) (probably not a real neoplasm) | Adults | Skull, tibia | Exophytic solid mass |

| Osteoid osteoma | Children, young adults | Tubular bones, lower extremity | Diaphyseal cortex “nidus” |

| Osteoblastoma | Children, young adults | Vertebra, spinal, transverse process | Similar to osteoid osteoma (“nidus”) |

| Osteochondroma (exostosis) | Young adults | Long bones | Bony exostoses with cartilaginous cap |

| Chondroma (enchondroma) | Adults | Tubular bones metacarpi, phalanges | Intraosseous, solitary well-circumscribed lesion |

| Chondroblastoma | Children, young adults | Long bones femur, tibia, humerus | Epiphysis, paraarticular well-circumscribed lesion |

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | Children, young adults | Femur, tibia | Excentric lucent defect, delicate sclerotic border |

| Synovial chondromatosis (self-limited) | Young adults (men) | Large joints | Hyaline cartilage nodules and floating free bodies |

| Villonodular synovitis Pigmented | Young adults | Knee, hip, ankles, feet, fingers | Synovial lining cell proliferation with hemosiderin deposits |

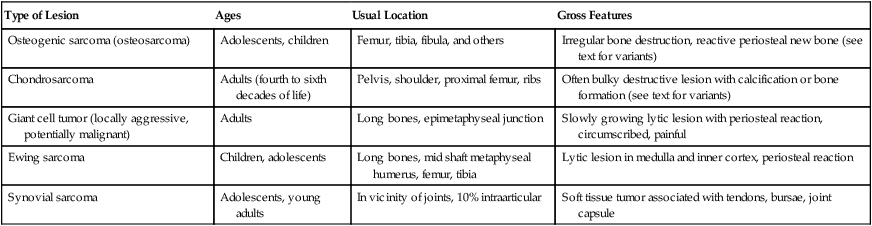

TABLE 11-4

MALIGNANT PRIMARY TUMOROUS LESIONS OF THE SKELETAL SYSTEM AND JOINTS

| Type of Lesion | Ages | Usual Location | Gross Features |

| Osteogenic sarcoma (osteosarcoma) | Adolescents, children | Femur, tibia, fibula, and others | Irregular bone destruction, reactive periosteal new bone (see text for variants) |

| Chondrosarcoma | Adults (fourth to sixth decades of life) | Pelvis, shoulder, proximal femur, ribs | Often bulky destructive lesion with calcification or bone formation (see text for variants) |

| Giant cell tumor (locally aggressive, potentially malignant) | Adults | Long bones, epimetaphyseal junction | Slowly growing lytic lesion with periosteal reaction, circumscribed, painful |

| Ewing sarcoma | Children, adolescents | Long bones, mid shaft metaphyseal humerus, femur, tibia | Lytic lesion in medulla and inner cortex, periosteal reaction |

| Synovial sarcoma | Adolescents, young adults | In vicinity of joints, 10% intraarticular | Soft tissue tumor associated with tendons, bursae, joint capsule |

TABLE 11-5

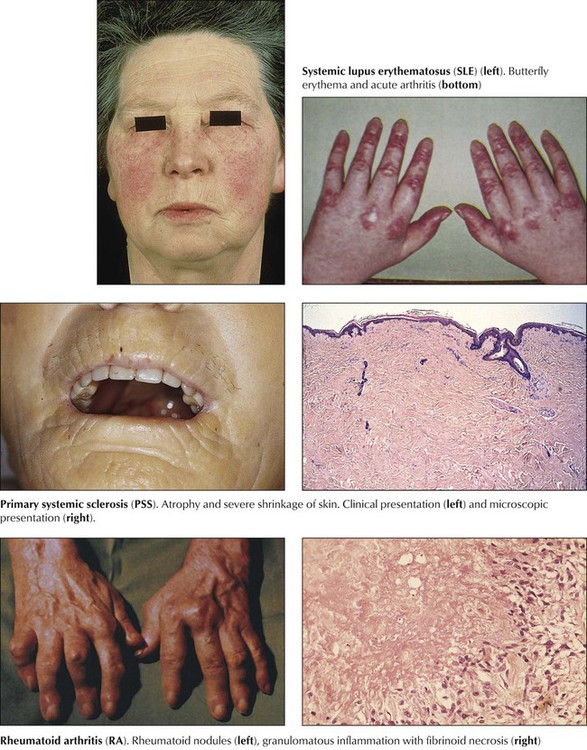

FEATURES OF EXEMPLARY MEMBERS OF COLLAGEN-VASCULAR DISEASES

| Syndrome | Autoimmunity* | Features† |

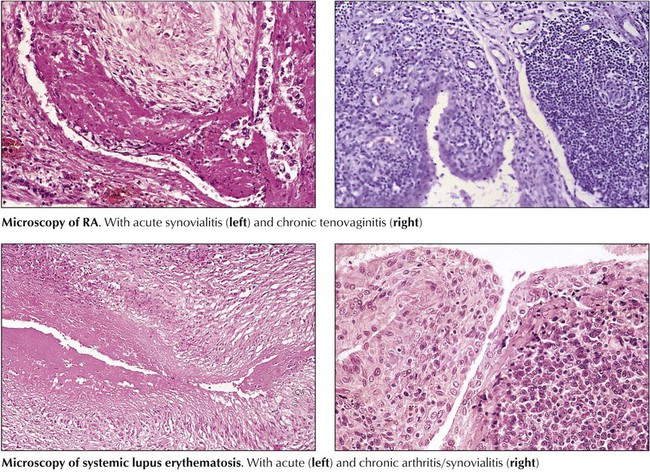

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Autoantibodies against native ds-DNA, denatured ss-DNA, histones, and histone complexes T-, NK-cell, and cytokine abnormalities, circulating immune complexes | Rashes, arthritis/arthralgia, glomerulonephritis, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, pleural effusions, pulmonary fibrosis, pericarditis, endocarditis, psychosis, seizures Vasculitis and thrombosis |

| Primary systemic sclerosis | Autoantibodies against small RNA protein (SS-A/Ro), topoisomerase I (Scl-70), 45K RNA protein (SS-B/La) | Hallmark: scleroderma, Raynaud syndrome, proliferative arteritis and fibrosis, capillary malformations such as telangiectasia and bleeding; esophagus and lower GI tract: fibrosis and muscular atrophy with motility problems and dysphagia, interstitial pneumonitis, “shrinking lung disease,” pulmonary hemorrhage; heart: conductive and ventricular dysfunction, renal vasculitis and hypertension |

| Polymyositis, dermatomyositis | tRNA synthetases: Jo-1, PL-7; protein complex (PM-Scl) | Muscle weakness: segmental myofiber necrosis with inflammatory infiltrate, fever, myoglobinuria, skin rash, erythema of hands (knuckles), interstitial pneumonitis, approximately 25% associated with malignancies |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Denatured ss-DNA Rheumatoid factor, CIC, antikeratin, collagen antibody, T-cell “activation” |

Chronic relapsing synovitis, arthritis, small joints of hands, symmetrical, tenosynovitis, soft tissue rheumatic nodules, pleuritis, pericarditis, vasculitis, interstitial pneumonitis, bronchiolitis obliterans, polyneuritis, mononeuritis, Felty syndrome |

CIC indicates circulating immune complexes; ds, double-stranded; GI, gastrointestinal; ss, single-stranded.

Osteoporosis refers to a condition of reduced mass of mineralized bone secondary to an imbalance between catabolic (↑) and anabolic (↓) bone metabolism. The loss of skeletal mass can reach a state where the mechanical stability of affected parts is no longer maintained and fractures occur. There are primary and secondary forms of osteoporosis, and localized or systemic changes are identified. The most well-known and frequent type of primary osteoporosis is old age osteoporosis (senile osteoporosis). Inactivity osteoporosis (immobilization osteoporosis) is a localized form of secondary osteoporosis Other pathogenetic categories of osteoporosis are summarized in Table 11-1.

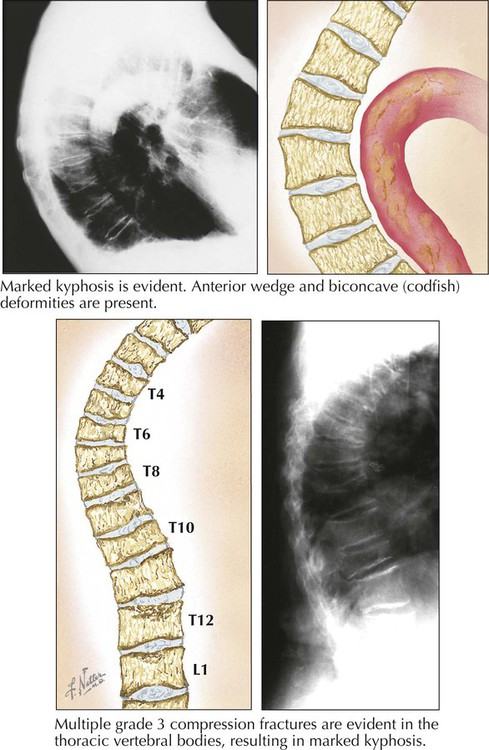

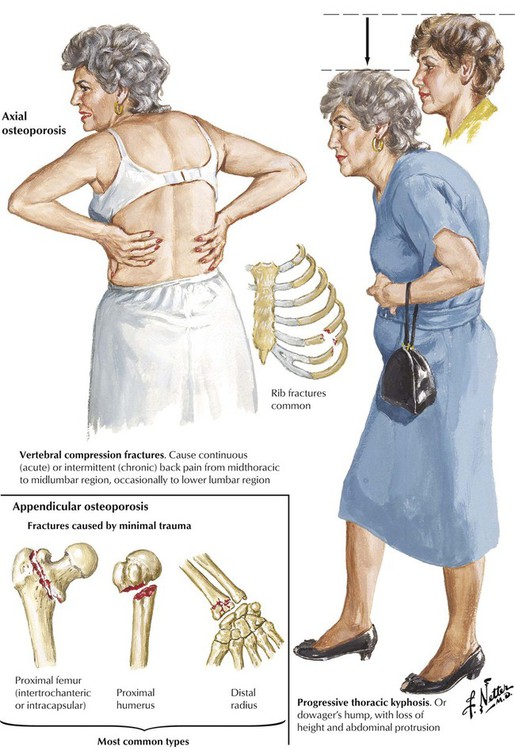

The anatomical and clinical manifestations of osteoporosis are dependent on the maximal bone mass (peak bone mass), which is genetically determined. It is higher in men than in women and lower in white populations than in others. Therefore, a white female is at highest risk. Bone mass is commonly determined by radiographic measurement of bone density, which is highest at the ages of 25 to 35 years and decreases gradually thereafter by approximately 0.7% per year. Gross and microscopic features of osteoporosis show a diffuse rarefaction of trabecular bone and a symmetric thinning of trabecular and cortical bone. The ratio of mineralized bone to osteoid remains normal. In postmenopausal osteoporosis, disruption of trabecular bone adds significantly to the instability of the skeleton. The most common fractures resulting from primary osteoporosis are hip fractures, compression fractures of vertebral bodies (8 times more frequent in females), and fractures of the distal radius.

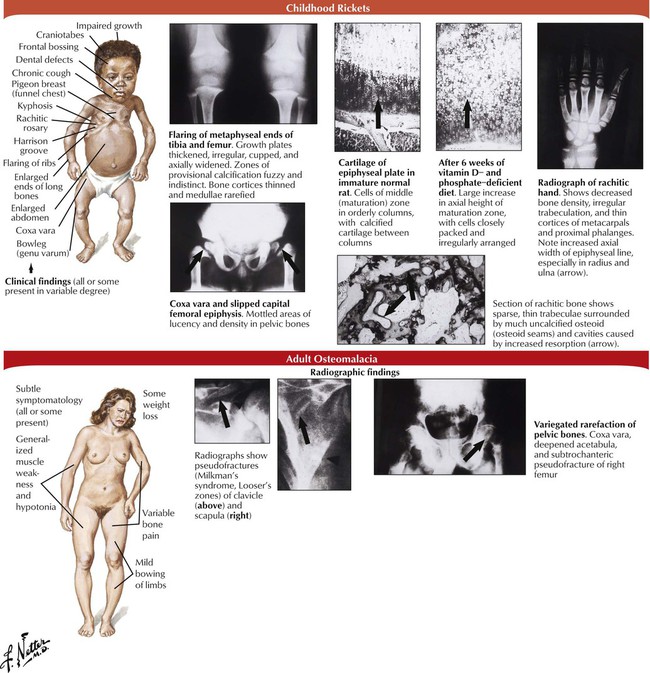

In rickets and osteomalacia, mineralization of osteoid is reduced while bone mass remains normal. Rickets affects the growing bones of children, and osteomalacia affects the newly formed bone matrix in adults. Responsible metabolic disturbances are vitamin D deficiency, phosphate deficiency, and mineralization defects (Table 11-2). Growing bone is severely changed in children with rickets because inadequate mineralization of osteoid matrix leads to overgrowth and distortion of epiphyseal cartilage projecting into the medullary space, disruption of osteoid/cartilage replacement, and reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibroblasts. Loss of structural stability causes skeletal bone deformations (thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, coxa vara, genu varum). Osteocartilaginous thickening of ribs produces characteristic rachitic rosary. Adults with osteomalacia experience only mild bowing of long bones; however, stress resistance of bones is reduced, and gross or microscopic fractures may occur.

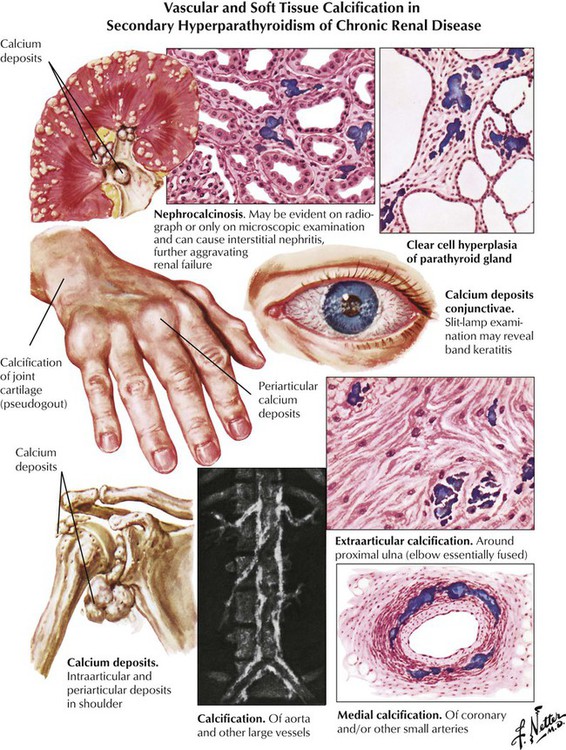

Renal osteodystrophy, which is most common in patients undergoing long-term dialysis for chronic renal failure, combines the changes of osteomalacia with focal soft tissue, bone resorption, and vascular calcifications (metastatic calcification). Tumorlike calcium deposits are observed in some cases. While osteomalacic changes suggest renal tubular damage, additional focal osteoclastic bone resorption is caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism. Therapeutic planning must focus on treating the chronic renal disease, replacing 1,25(OH)2-D, substituting for hypophosphatemia, and partially resecting hyperplastic parathyroid glands.

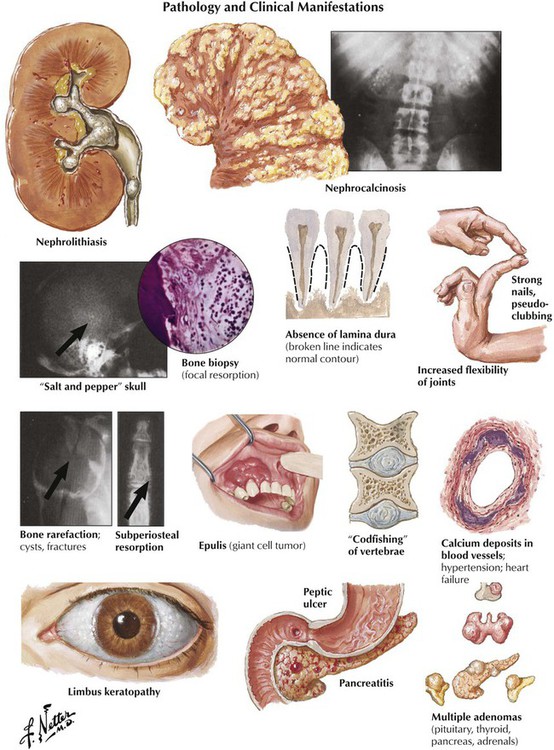

Primary hyperparathyroidism causes generalized bone resorption by focal osteoclastic activities (as described in osteitis fibrosa cystica) combined with an increased incidence of stone formation (e.g., nephrolithiasis). Osteoclastic hyperactivity starts at subperiosteal and endosteal surfaces, cutting into the bone and replacing respective splits and holes by connective tissue (dissecting osteitis). Areas of hemorrhage and microfracture may occur. Larger cystic spaces occur eventually, hemorrhage expands, and resorptive giant cell granulomas develop (“brown tumors” in osteitis fibrosa cystica). These must be distinguished from aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs), giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone, and telangiectatic OS. Characteristic radiographic changes in hyperparathyroidism are found preferentially in the hands (radial phalanges of the second and third fingers), with signs of focal calcinosis in the spine and the cartilage of major joints.

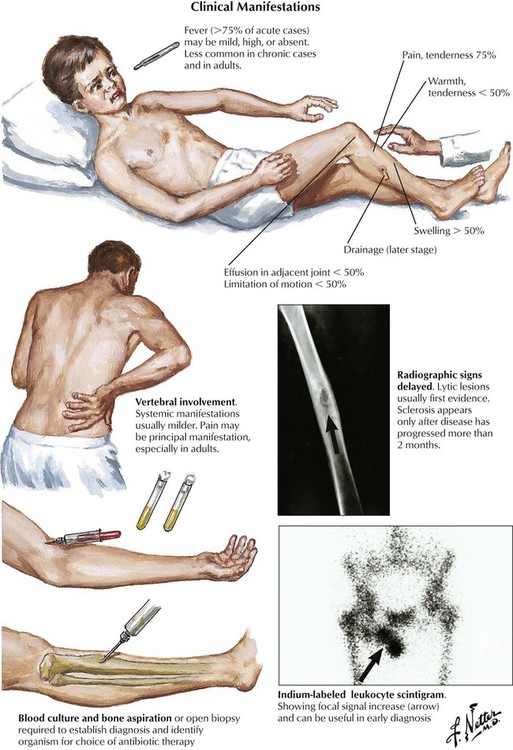

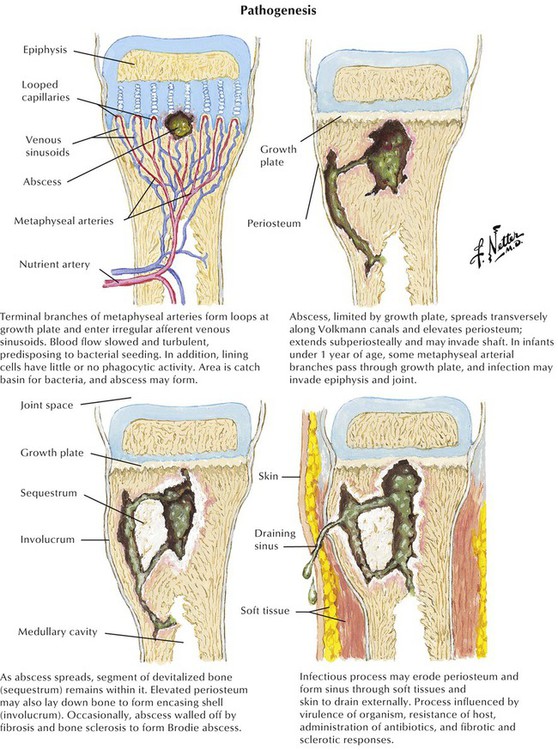

Although osteomyelitis (OM) can easily be suspected from persistent purulent secretion from deep open wounds or fistulas extending to the bone, the clinical manifestations of hematogenous OM are more difficult to identify. Obscure back pain, low-grade fever, malaise, and moderate blood leukocytosis are among uncharacteristic general symptoms. If localized signs appear, such as circumscribed bone pain, reddening and swelling of the covering skin or mucous membranes, or even fistula formation with purulent discharge, radiographic procedures and tissue biopsies may reveal the real nature of the disease. The most common organisms causing OM are Staphylococcus aureus (e.g., after long-standing infected intravenous catheters, endocarditis, or complicated wound healing), various gram-negative rods, pneumococci (in neonates), salmonellae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

At the site of bacterial nesting in the bone, usually at well-vascularized metaphyseal sites, acute endotheliitis/vasculitis with subsequent neutrophilic exudation and necrosis of adjacent bone develops. Necrosis may follow local vascular occlusion by thrombosis, compression and hypoxemia, or both. Infection spreads through the marrow cavity and cortical bone, extending subperiosteally, transperiosteally, and through soft tissues, creating draining sinuses (fistulas). Progression to chronic OM adds focal osteoclastic bone resorption and fibrous repair mechanisms. Bony cavities may contain fragments of necrotic bone (bony sequester) surrounded by hyperostotic bone (involucrum). Persistent abscesses are surrounded by condensed sclerotic bone (Brodie abscess). Periosteal and osteal hyperostosis on radiograph may signal underlying chronic OM. Microscopic features include decreased neutrophils, persistent edematous swelling, scattered plasmacytic infiltrates, and progressive fibrosis.

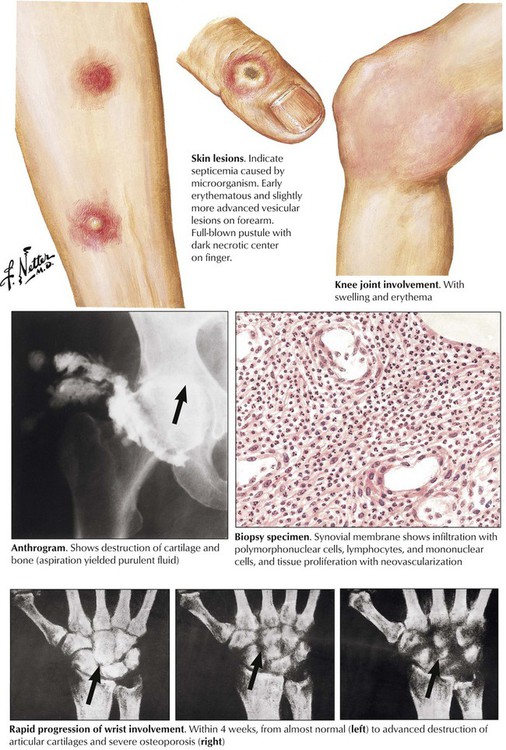

Infectious arthritis is an acute or chronic inflammation of a joint or joints, usually caused directly or indirectly by specific infectious organisms. Infectious arthritis is caused directly by seeding of such pyogenic organisms as gonococci, staphylococci, meningococci, and pneumococci. Infection results in a characteristic edematous and neutrophilic infiltration of the synovialis with hemorrhage or necrosis (according to endotoxin or exotoxin activities) and with subsequent lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, capillary proliferation, and fibrosis, depending on the duration of the process. Destruction of cartilage and fibrous adhesions may cause final joint dysfunction and ankylosis.

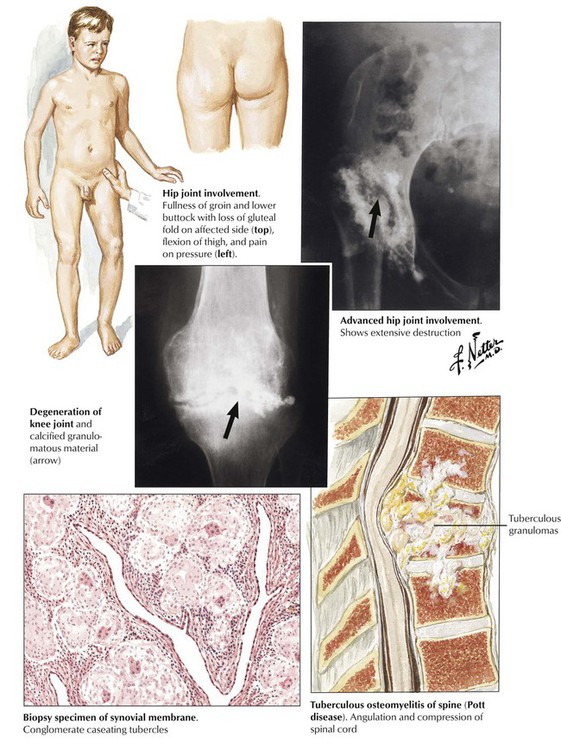

Tuberculous arthritis is characterized by granulomatous reaction and runs a primary chronic course. It is the consequence of hematogenous spread of organisms, usually during early or later phases of stage II tuberculosis (early or late post–primary tuberculosis). Infection usually affects only one joint, most frequently the spine, the hip, the knee, the elbow, or the ankle. The onset of symptoms is insidious; frequent local muscle spasms at night may be the first suspicious sign of the disease. Walking may be problematic if the spine is involved (Pott disease). Radiographic changes and strong positive tuberculin skin test results are helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Diagnostic proof is given by tissue biopsy and the demonstration of acid-fast bacilli in the granulomatous inflammation as well as by culture or polymerase chain amplification reaction (PCR) techniques.

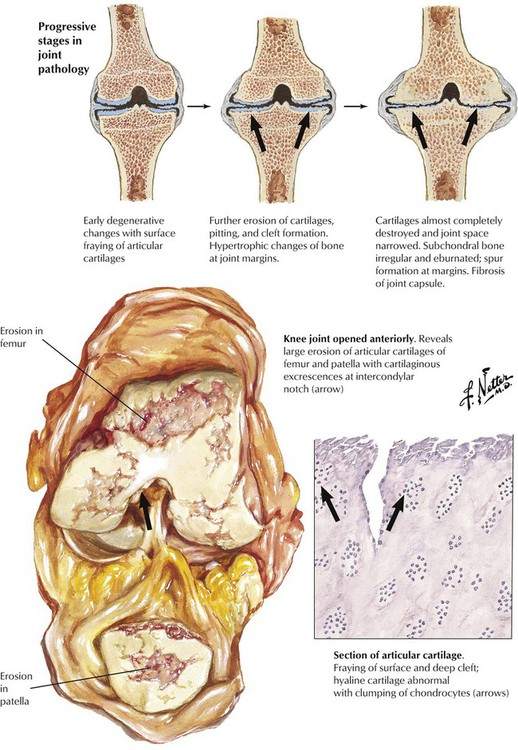

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common degenerative joint disease causing physical disabilities in persons aged older than 65 years. Initial changes, which become overt by the age of 20 years in 4% of the population, increase steadily to affect more than 85% of persons by the age of 75 years. Primary OA is thought to result from intrinsic defects of cartilage. Secondary OA results from conditions such as malformations, trauma, and metabolic diseases with or without crystalline deposits. Several pathogenetically important factors may contribute to the development of OA: abnormal mechanical forces on the cartilage (increased unit load), decreased water bonding of cartilage (decreased resilience), increased stiffness of subcartilaginous bone, and biochemical abnormalities such as decrease in proteoglycans and shortening of glucosaminoglycans. The latter decreases cartilaginous water binding in favor of binding by collagen fibers. Genetic factors may favor mutations of the collagen type II gene.

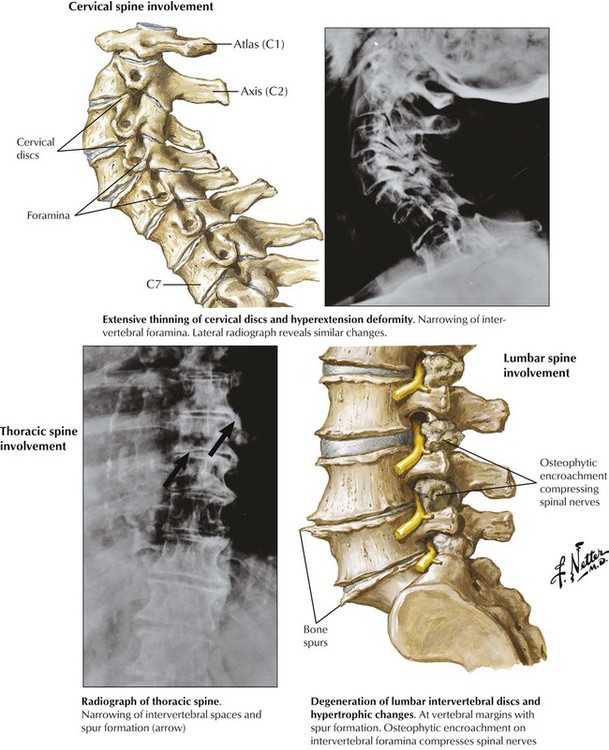

Signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis (OA)—morning stiffness and pain, rubbing sounds (crepitus), and tenderness and swelling of soft tissues covering joints—develop gradually, most often in the knees, the hips, the lumbar and cervical spine, and the finger joints, leading eventually to muscle contracture and compromised joint mobility. Early microscopic findings are loss of cartilaginous metachromatic staining (loss of proteoglycans), loss of chondrocytes, reactive hypertrophy and grouping of residual chondrocytes, and fibrillation and splitting of the cartilage surface. Fibrillation favors infiltration by synovial fluid with further enzymatic damage, inflammation, and cartilage destruction. Granulation tissue and fibrosis replace cartilage, and erosions result in open bony surfaces. Reactive new bone formation (osteophytes) and fibrous adhesions in border zones limit movement. Circumscribed areas of destruction with fragments of cartilage, dead bone, and synovial fluid may expand into the adjacent bone, forming debris-laden subchondral cysts.

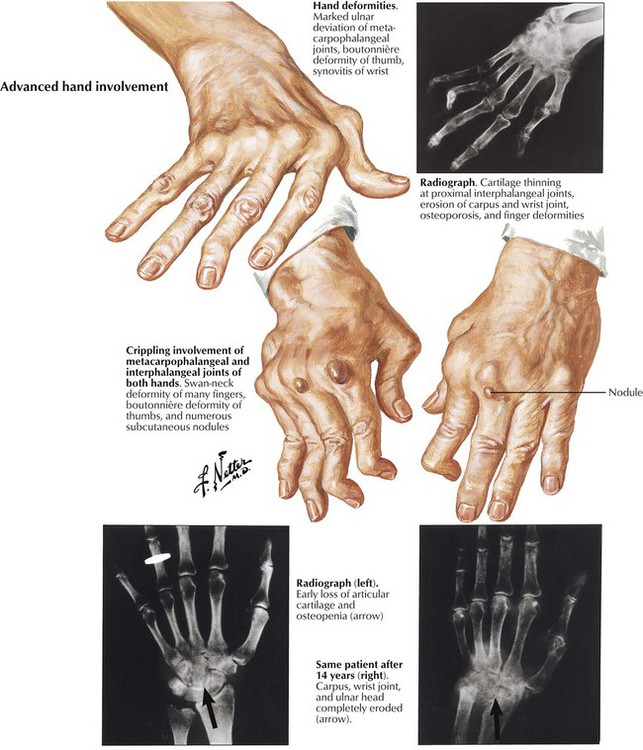

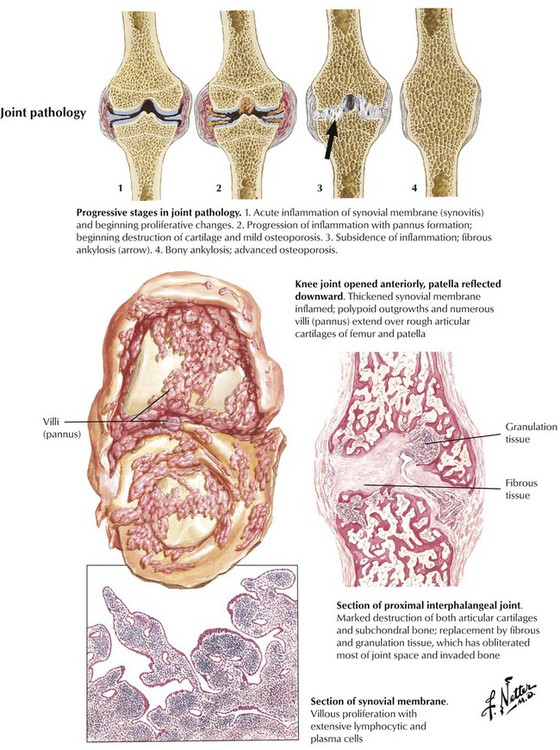

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic chronic progressive inflammatory disease with symmetric involvement of small joints. Variants are Still disease in children (juvenile arthritis) and ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew disease) preferentially involving the vertebral column and the sacroiliacal joints. RA is representative of a group of autoimmune disorders referred to as collagen–vascular diseases, which include lupus erythematosus, primary systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, and dermatomyositis. The etiology of RA is unknown; however, its pathogenesis includes genetic factors (prevalence of HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR1 genes and others), autoimmune reactions (possibly postinfectious), and local factors such as mechanical stress and specifics of tissue reactivity.

Microscopic features of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are progressive villous hypertrophy of the synovialis secondary to fibrinous swelling, proliferation of synovial lining cells, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. With increasing chronicity, acute inflammatory reactions are replaced by granulation tissue and fibrosis covering and eroding the cartilaginous surface of the joints (pannus formation). Joint mobility is severely inhibited with grossly impressive deviations (subluxation) of joints. End-stage disease is characterized by complete fibrous obliteration of the joints. Adjacent soft tissues may contain focal granulomas with binucleated giant cells (Aschoff cells) surrounding soft tissue fibrinoid necrosis (rheumatic nodule). Although 25% of patients with RA may recover completely, 50% experience terminal severe incapacitation. Death usually occurs from complications such as infections, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or cardiovascular or pulmonary involvement.

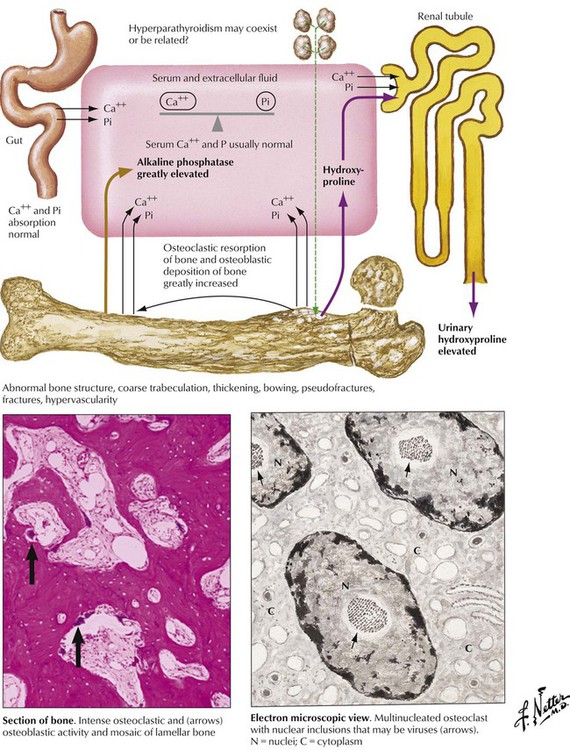

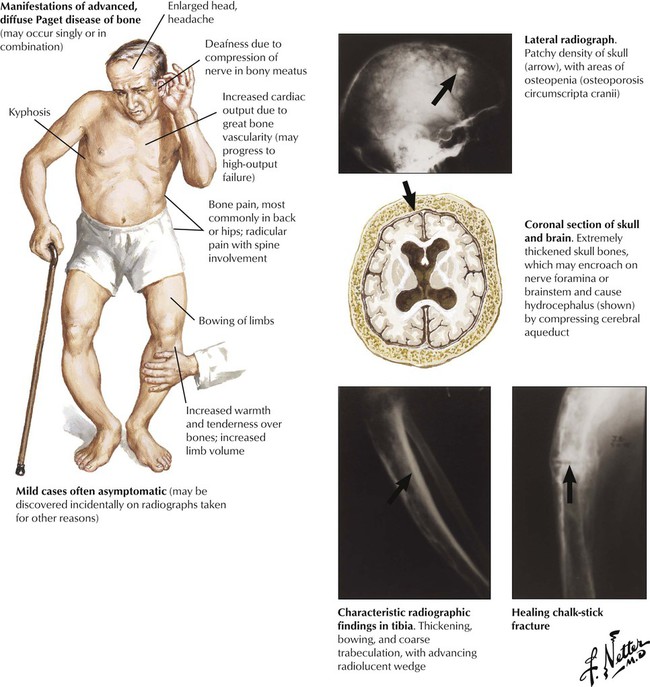

Paget disease (osteitis deformans) is characterized by excessive osteoblastic bone formation with abnormal structure and impaired stability. It occurs with increasing incidence after the age of 40 years (4-10% of the population), primarily in white populations, more often in men than in women. PD may occur in a monostotic form (one bony site) or in a systemic polyostotic form. In the initial stage, osteoclast hyperactivity with increased lacunar bone resorption is seen; the presence of respective inclusion bodies and viral transcripts (resembling paramyxovirus) suggests it is stimulated by infection with a slow virus. In the second stage, marked osteoblastic hyperactivity compensates and then overcompensates for the osteoclast function, and excessive disorderly new bone with irregular cement lines (mosaic bone) is produced. The final stage (“cold” or burnt-out phase) is characterized by marked thickening of densely mineralized bone (osteosclerotic phase) with minimal cellular activity.

Early phases of Paget disease (PD) are asymptomatic, although incidentally increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels may suggest a skeletal disorder. In more advanced cases, incidental radiographic findings may suggest the disease. Typical features are enlargement of head bones, headache, deafness and visual disturbances, deformation and tenderness of long bones (especially of the lower extremities), back pain, and fractures (vertebra, chalk-stick–type cross-fractures of long bones). OS develops in approximately 1% of patients.

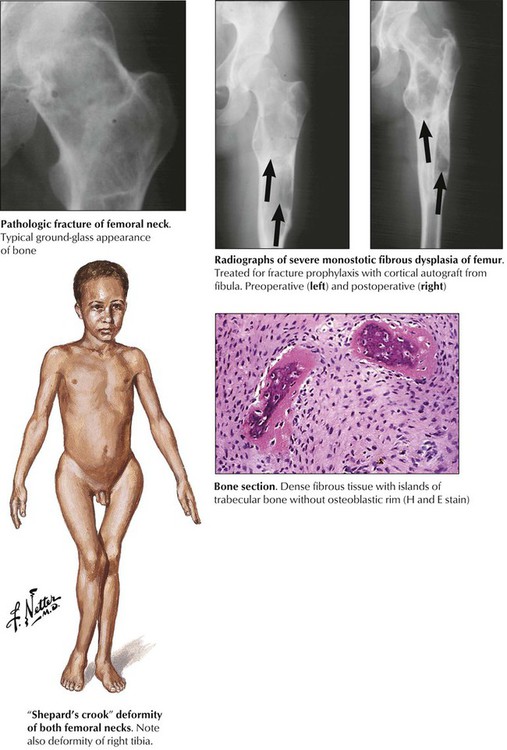

Fibrous dysplasia (FD) is a tumor-imitating developmental abnormality of bone that consists of circumscribed mixed fibrous and osseus lesions. FD may be associated with endocrine abnormalities and skin pigmentation such as precocious puberty and café au lait spots (McCune-Albright syndrome), acromegaly, and Cushing syndrome. Monostotic and polyostotic forms frequently occur in the proximal femur, the tibia, the ribs, and the mandible. Polyostotic forms (25%) also may involve the pelvis, the hands, or the feet. Growing lesions cause pain, deformation of bones, and pathologic fractures. Characteristic radiographic findings show a ground-glass, slightly “multivesicular” (“soap bubble”) appearance with distinct borders. Microscopy shows a dense whorled fibrous tissue containing spicules of woven bone. The prognosis of FD is good, and management should prevent complications such as fractures. Rarely, malignant sarcomas may complicate the course of FD. See Table 11-3.

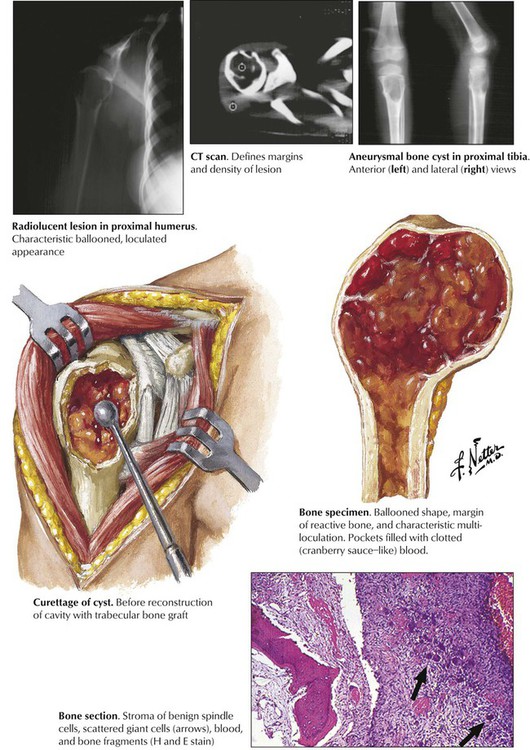

Aneurysmal bone cysts are not a true neoplasm but a reactive tumorlike lesion arising suggestively from previous trauma or degeneration of another underlying disease (e.g., osteoblastoma, FD, GCT, and others). Grossly, ABCs appear as circumscribed masses of spongy, bloody tissue with fibrous septae, thinning the cortical bone, and bulging through the periosteum. Part of the bone may be replaced by granulation tissue with microscopic multinucleated giant cells and osteoid bone formation. Although lesions usually enlarge rapidly, there are slow-growing types of ABC that must be distinguished from the malignant telangiectatic osteosarcoma and giant cell tumor of bones. Bone scans and computed density measurements may be helpful in the differential diagnosis, but biopsy and pathologic investigation are necessary to confirm ABCs. Local curettage with grafting of trabecular bone is the treatment of choice. See Table 11-3.

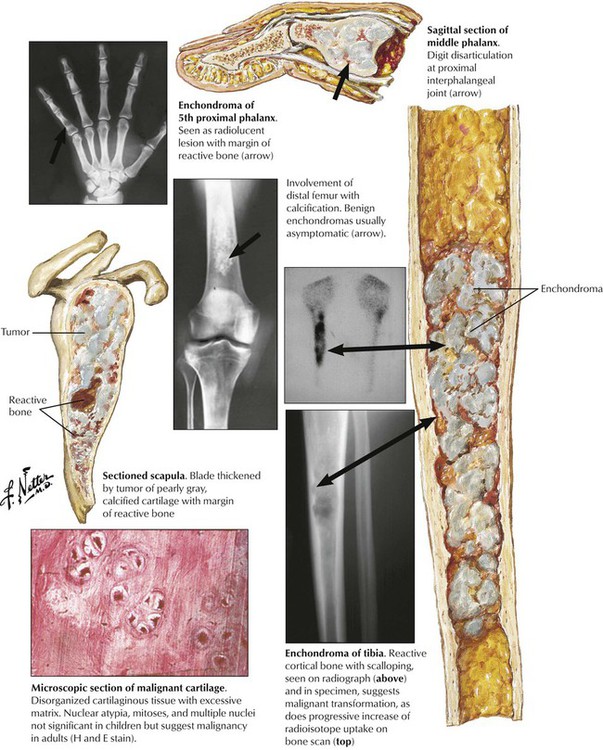

Enchondroma (EC) is a benign intraosseous tumor of well-differentiated cartilage occurring primarily in adults and adolescents. It most frequently affects small tubular bones of the hands and feet but can develop anywhere in the skeleton. The monoclonality of chondrocytes in EC suggests a benign neoplasm. EC may occur in multiplicity (enchondromatosis, Ollier disease). Rarely, EC transforms to secondary chondrosarcoma (CS). EC is usually asymptomatic except for certain “obscure” pain sensations. Incidental radiographs show well-defined radiolucent lesions with slightly pronounced bony margins and sometimes calcification. Microscopy reveals a somewhat disorganized, well-differentiated cartilage with stippled calcification. Larger lesions may undergo pseudocystic degeneration. The prognosis for small benign ECs is good, and lesions may be followed without intervention. Surgical intervention is suggested for mechanical reasons or when suspicion of malignancy arises. See Table 11-3.

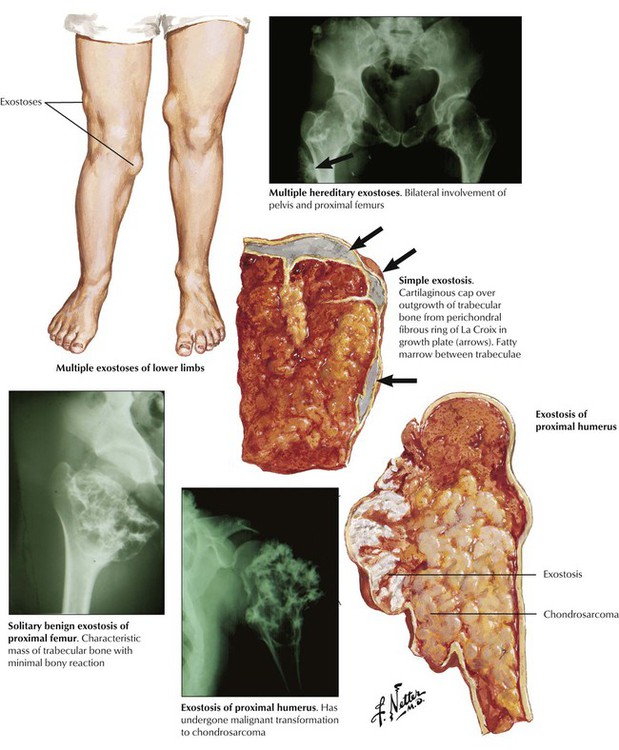

Osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostoses), which constitute approximately one third of benign bone tumors, are not tumors as such but rather developmental dysplasias of the growth plate. Osteochondroma presents as a solitary lobulated metaphyseal outgrowth, polyostotic, or rarely as a familial disorder (multiple hereditary exostosis) and consists of mature trabecular bone with a cartilaginous cap. Common locations are the proximal and distal femur, the proximal humerus and tibia, and the pelvis and scapula. Radiographic and gross changes are characteristic. Rapidly growing lesions in adults may indicate a (rare) risk of malignant transformation to secondary chondrosarcoma. These lesions must be distinguished from parosteal osteosarcoma. The prognosis of solitary exostosis is excellent, with approximately 5% recurrence after surgical removal. See Table 11-3.

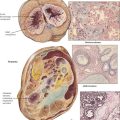

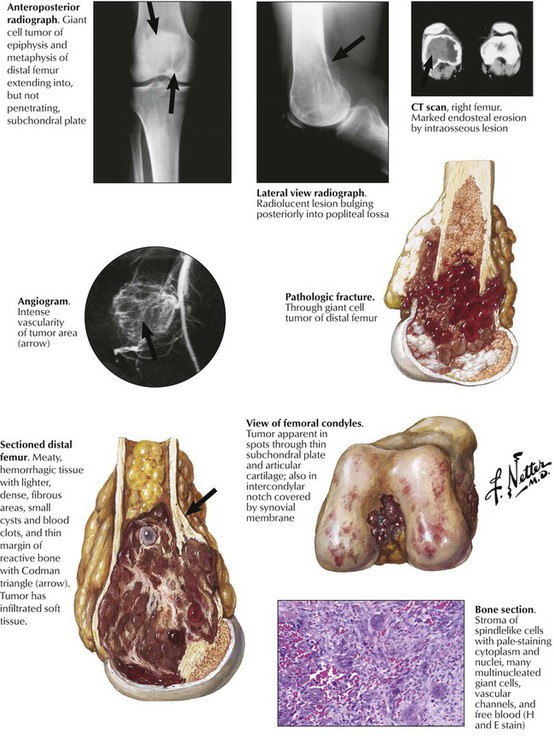

Giant cell tumor of bone (osteoclastoma) occurs preferentially between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Typically, the lesion is located at the epimetaphyseal junction of long bones such as the femur, the tibia, the humerus, the radius, and the fibula, presenting as a slowly growing lytic lesion causing persistent intraosseous pain, reactive effusions, and eventual fractures. Radiographs reveal large radiolucent lesions with surrounding reactive bone formation, cortical thinning, trabecularization, and bony separation. Grossly, they appear as soft, friable, reddish-brown tissue resembling a bloody sponge. There may be areas of aneurysmal cavitation. Microscopically, they show a mixed-cell proliferation of stromal mononuclear cells and multinucleated (osteoclastic) giant cells in a markedly vascularized stroma and focal hemorrhages. Up to 10% (usually the incompletely removed tumors) metastasize; the neoplastic component is the mononuclear stromal cells. Treatment by curettage alone results in 50% recurrence. See Table 11-3.

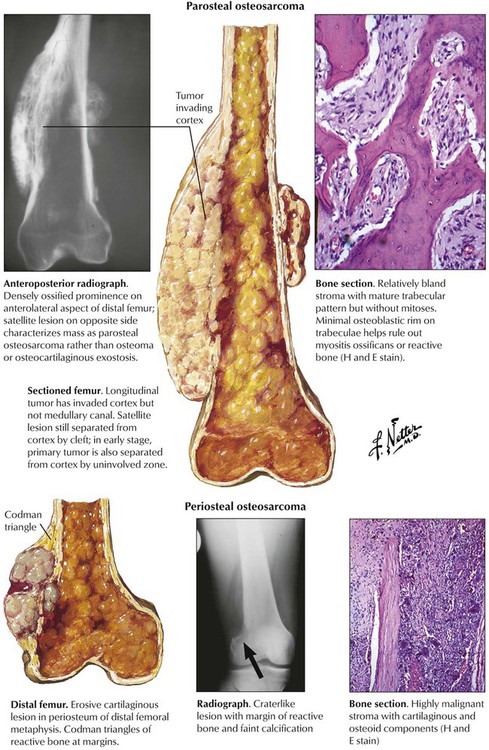

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) is the most common malignant bone tumor, occurring in endosteal, cortical or parosteal juxtacortical forms, usually during the second decade of life. Most frequent sites (75%) are metaphyseal areas adjacent to knee or shoulder (e.g., tibia, fibula, humerus), hands, feet, skull and jaws. Radiographs show localized lytic or osteoblastic lesions with fuzzy borders and prominent subperiosteal reactive bone formation (Codman triangle). The cut surface depends on the histologic variant of the tumor: it is whitish soft or bony hard, pseudocystic with focal necroses or hemorrhages and freely invades into adjacent soft tissues. Parosteal OS may resemble exostoses with well-differentiated bone or fibrous tissue components. Histologic variants include degrees of differentiation of chondroblastic areas or of giant cell components and overtly telangiectatic or fibroblastic forms. OS readily metastasizes into the lungs and pleura, less frequently to other organs. See Table 11-4.

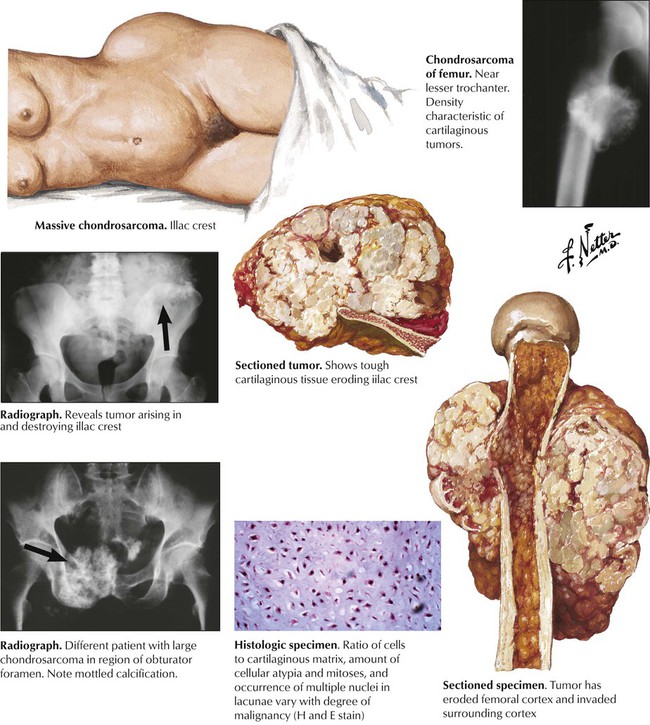

Chondrosarcoma arises from cartilage rests or preexisting ECs. There are several gross variants: central, juxtacortical and peripheral (the latter arising outside the bone). CSs occur in older persons with a peak in the sixth decade of life, usually in central portions of the skeleton such as shoulder, pelvis, proximal femur and ribs. Radiographic images show a bulky osteodestructive lesion with a characteristic pattern of calcification (“salt and pepper” or “popcorn”). Gross lesions show a smooth whitish glistening cut-surface that is occasionally lobulated and focally calcified. Histologic appearances vary from well differentiated cartilaginous tumors to undifferentiated and mesenchymal forms. Well-differentiated OS can be hard to distinguish from EC. Criteria of malignancy are the grouping and polymorphism of chondrocytes, their nuclear atypia, multinucleate cells and occasional mitoses. CSs metastasize preferentially to the lungs. See Table 11-4.

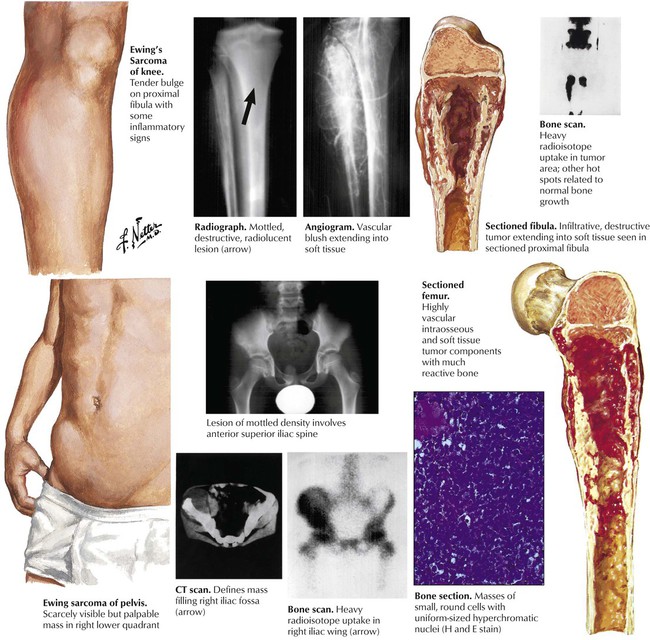

Ewing sarcoma (ES), after OS the second most common bone tumor in children, accounts for approximately 5% of all bone tumors and has a peak incidence in the second decade of life. Although its histogenesis remains unclear, frequent genetic mutations (t[11;22]p13;q12) suggest a relationship of malignant cells in ES to primitive neuroectodermal cells. Unlike other bone tumors, ES frequently presents with fever and pain simulating an inflammatory disease. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy and microscopic investigation. The characteristic dense small cell tumors must be distinguished from cell tumors such as neuroblastoma and malignant lymphoma. Long bones including midshaft humerus, tibia and femur are the sites most frequently affected. Grossly, the tumor impresses as osteolytic soft grayish-white masses with focal hemorrhage which may penetrate the periosteum and invade adjacent soft tissues. ES commonly metastasizes to lungs, brain and other bony sites such as the skull. See Table 11-4.

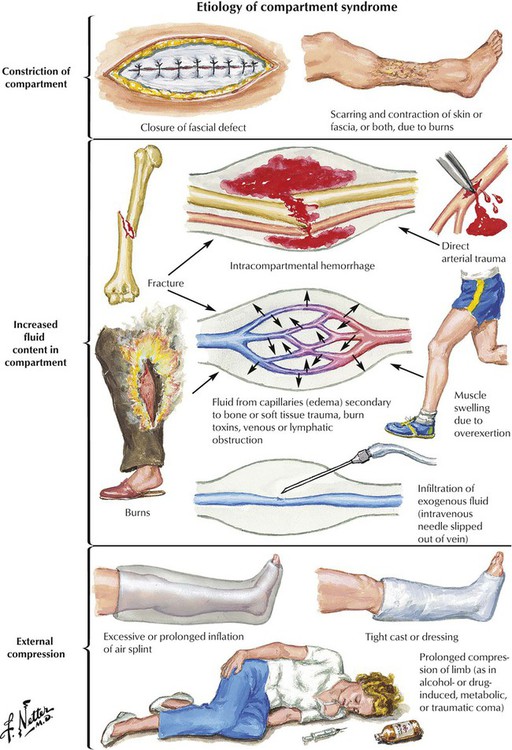

Compartment syndrome (CS) results from increased pressure in one or more (osteo)fascial compartments. Sustained increase of tissue pressure from local edema reduces capillary perfusion below the level necessary for sustaining tissue viability; irreversible muscle and nerve damage results in a few hours. Partial burial, trauma, burns, or exercise may cause CS. Pathogenetic mechanisms are increased fluid accumulation, decreased tissue volume (compartment constriction), and restricted volume expansion secondary to external compression (e.g., casts). In conscious patients, pain is disproportionate to the obvious injury and increases with passive stretching of muscles. Loss of sensation from nerves running through affected compartments may occur. Microscopic changes are intense soft tissue edema with progressive degeneration and necrosis, hemorrhage, and, in delayed cases, slowly developing granulation tissue and fibrosis. There is high risk of superinfection, and secondary septicemia exists.

Collagen-vascular disease (CVD) refers to a group of systemic autoimmune disorders with overlapping signs and symptoms that affect several organ systems (e.g., skin, kidneys, lungs). CVDs include systemic lupus erythematosus, RA, primary systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and certain “overlap syndromes” (Table 11-5). Although the etiologies of CVDs are unknown, the pathogenesis is characterized by various autoimmune reactions with demonstration of respective autoantibodies, circulating immune complexes, or both. The essential pathologic features in all CVDs are chronic inflammatory infiltration (lymphoplasmacellular) of connective tissue, edema, fibrinoid necroses, vasculitis, and progressive fibrosis. The extent and composition of these features vary among the different CVDs and with their type of autoimmune reaction (autoantibodies, circulating immune complexes, T-cell immune reaction).

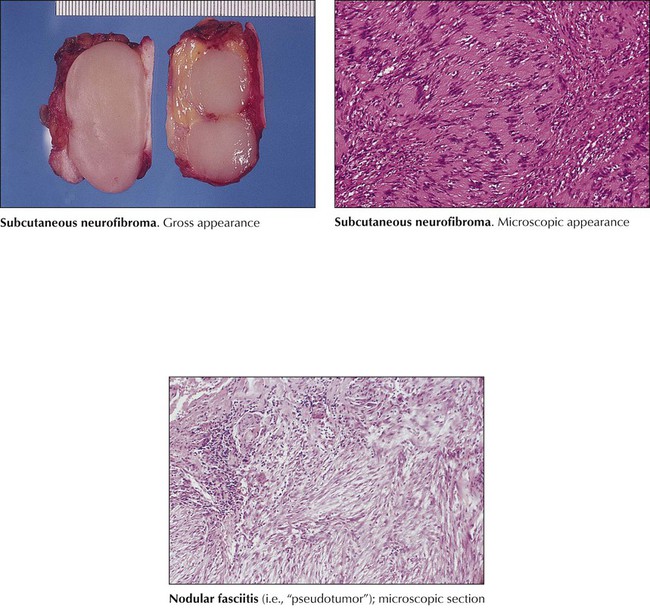

Benign tumors of soft tissue may occur at any age and are classified according to the tissue where they arise: fibromas, lipomas, rhabdomyomas, leiomyomas, or mixtures of these, and composite tumors with additional tissue components (angiolipomas, fibrous histiocytoma, neurofibroma, myelolipoma). Subcutaneous lipomas, the most frequent benign tumors, are slowly enlarging well-circumscribed yellowish masses with a histology indistinguishable from normal fat tissue. Fibrous tumorlike lesions (nodular fasciitis, fibromatosis) are not considered real tumors, although some show locally aggressive behavior. Fibrous histiocytomas are dermal tumors of interlacing fibrous strands and collections of lipid- and iron-containing histiocytes. Benign neurofibromas occur in dermis and in part in the submucosa of the alimentary tract. They may cause bleeding or mild obstruction. Leiomyomas are common in the uterus but also are found in the gastrointestinal tract or originating from blood vessels.

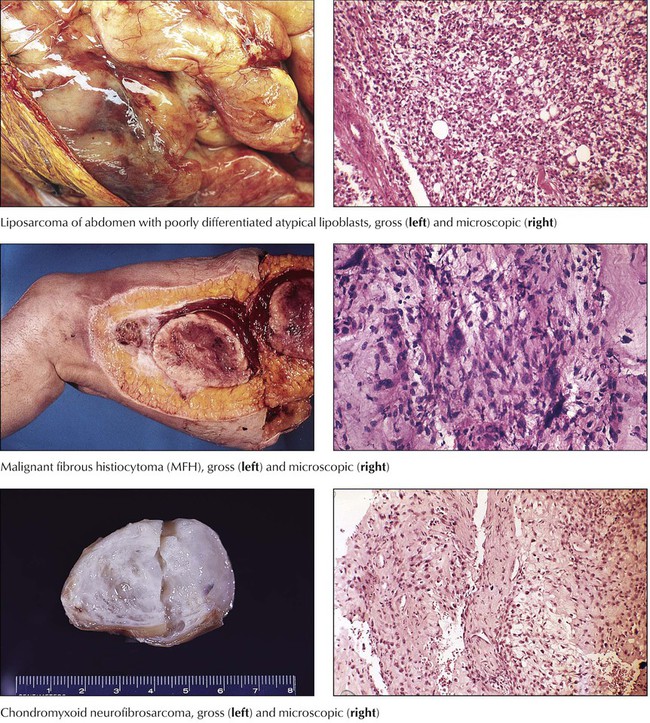

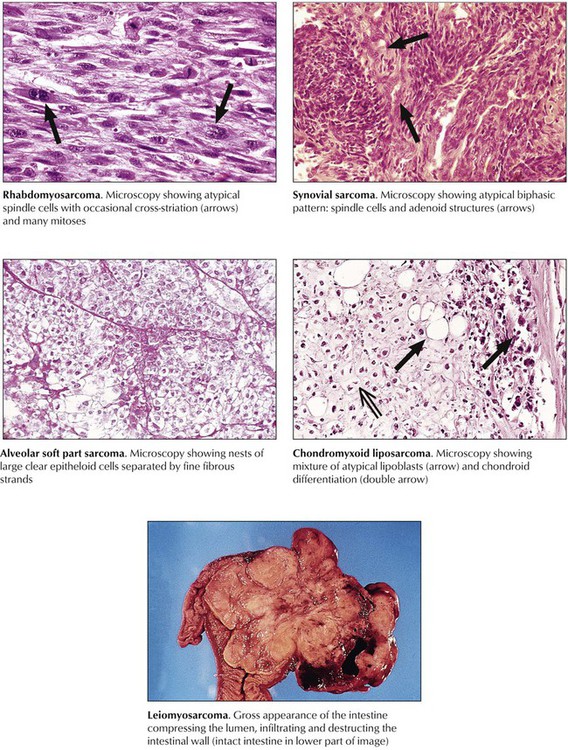

Sarcomas spread by hematogenous metastases rather than through lymphatic channels. They are classified according to the tissue from which they derive, or in a more descriptive way if their histogenesis is unclear. Variants include liposarcomas, fibrosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), neurofibrosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, leiomyosarcomas, and alveolar soft part sarcomas or epithelioid sarcomas. Fibrosarcoma, usually arising from fascia, tendons, periosteum, or scar tissue of the thigh, the knee, or the trunk, is not a common malignancy, but its “pleomorphic cousin,” MFH, is the most common soft tissue sarcoma. MFH is a highly malignant tumor of deep fascia, skeletal muscle, and the retroperitoneal space, preferentially occurring in patients aged 50 to 70 years. Postradiation fibrosarcoma is classified as MFH. Prognosis depends on the degree of atypia and the polymorphism of its cells. Approximately 50% of MFHs metastasize early to the lungs. Liposarcomas arise preferentially in the deep subcutaneous tissues of the thighs, the abdomen, and the retroperitoneum of persons aged older than 50 years. There are several morphologic variants (e.g., well-differentiated, myxoid, pleomorphic, and round cell forms), some of which show mutational chromosomal abnormalities of their adipocytes. Rhabdomyosarcoma is a tumor of children and young adults. It is thought to derive from primitive mesenchyme or embryonic muscle tissue and has corresponding appearances: embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. Well-differentiated forms contain plump cells resembling striated muscle. Leiomyosarcomas are malignant tumors of smooth muscle, occurring most commonly in the uterus and gastrointestinal tract. Neurofibrosarcoma and neurolemmal sarcoma (malignant schwannoma) are tumors of peripheral nerves that are more common in adults. Epithelioid sarcomas and alveolar soft part sarcomas are rare, highly malignant tumors of uncertain histogenesis.