60 Bone Neoplasms

Osteosarcoma

Clinical Presentation

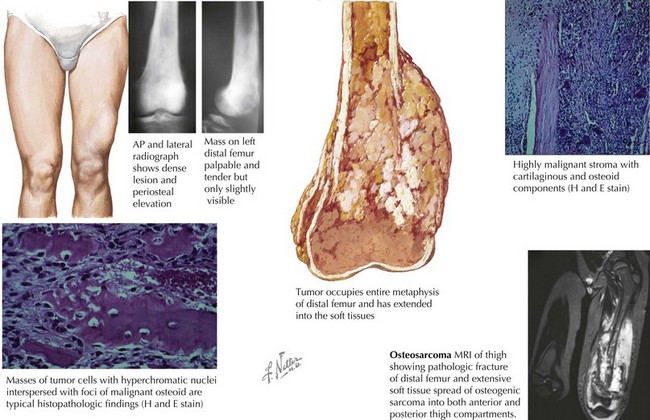

The most common clinical symptom at presentation is pain, often described as dull and aching, and typically of several months’ duration. Other complaints include a palpable mass with or without swelling. Systemic complaints such as fevers, weight loss, and decreased appetite are rare. Eighty percent of OS occur in the extremities, and on examination, a mass (tender or nontender) may be noted (Figure 60-1). The examination may also reveal decreased range of motion or muscle atrophy. Regional lymphadenopathy is rare. The most common sites of disease include the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus, although OS may occur in any bone. Involvement of the axial skeleton can occur but is less common. Eighty percent of patients with OS have localized disease at the time of diagnosis. The lung is the most common site of detectable metastatic disease at diagnosis, although patients may present with multifocal bone disease without pulmonary involvement.

Evaluation

Imaging studies are more helpful in making the diagnosis of OS than are laboratory tests. A plain radiograph will often reveal a lytic or blastic lesion of the bone with poorly defined borders (see Figure 60-1). Other findings include periosteal elevation adjacent to the primary lesion, a sunburst appearance, or a pathologic fracture. If OS is suspected, chest computed tomography (CT) and bone scan can be used to assess for pulmonary and bone metastases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed to better evaluate the extent of the tumor and should include the joint above and below the involved area so that skip lesions are not missed (see Figure 60-1). In addition to delineating the intra- and extraosseous extent of the tumor, the MRI may provide information regarding tumor effects on critical neurovascular structures.

Under the microscope, OS classically appears to be composed of spindle cells associated with malignant osteoid (see Figure 60-1). The extent of osteoid production may vary among the osteoblastic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic, telangiectatic, and small cell subtypes; however, the presence of tumor osteoid is the key pathologic feature of this disease.

Ewing’s Sarcoma Family of Tumors

Clinical Presentation

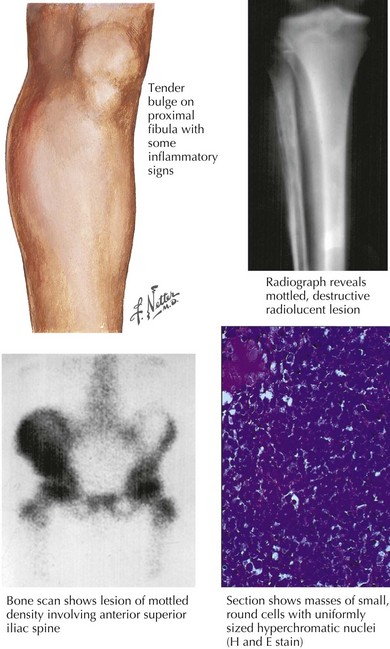

As in patients with OS, the most common presenting symptom of patients with ESFT of bone is pain. Before the diagnosis of the malignancy, bone pain may have been attributed to trauma or to athletic activities. As a result, the duration of symptoms before diagnosis may range from weeks to years. In addition to pain, patients may also complain of swelling or a palpable mass (Figure 60-2). Tender soft tissue masses may be palpable on examination. Fever and weight loss may be seen in patients with large tumors, but these symptoms are more common in the 25% of patients found to have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Patients with tumors of the axial skeleton may present with neurologic symptoms, including paraplegia or bowel or bladder dysfunction, secondary to the paraspinal locations of these tumors.

Evaluation

Radiography is typically the first imaging modality used to evaluate the primary site of disease (see Figure 60-2). Bony destruction with “onion skinning” of the periosteum may be seen. Tumor growth may lead to elevation of the periosteum and the formation of a triangular interface between the tumor and normal bone known as Codman’s triangle. MRI of the primary site is critical in determining the extent and size of an ESFT involving bone, and the relevant bone or compartment should be imaged in its entirety.

Under the microscope, ESFT appear to be composed of sheets of small, round, blue cells with scant cytoplasms (see Figure 60-2). The peripheral primitive neuroectodermal variant of ESFT may appear to contain aggregates of cells known as Homer-Wright rosettes. ESFT cells will frequently demonstrate membranous CD99 (cluster of differentiation molecule) positivity with immunohistochemical staining. CD99 staining is helpful in making the diagnosis of ESFT, but CD99 positivity can be seen in cells other than ESFT cells, including lymphoblasts. For this reason, molecular diagnostic studies are of critical importance in the ES tumor setting. In 95% of cases, a rearrangement involving the EWS (ES) gene is detected. Most occur via a t(11,22) translocation, which results in production of the EWS-FLI1 fusion protein. In approximately 10% of cases, other members of the ETS transcription factor family, including ERG, ETV1, or E1AF, are involved in gene rearrangements in ESFT. EWS rearrangements can be detected by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction or by fluorescent in situ hybridization.

After confirmation of the diagnosis of ESFT, a staging evaluation must be performed. The most common sites of metastatic disease at diagnosis are lung, bone, and bone marrow. CT of the chest and bone scintography are used for detection of metastatic pulmonary and skeletal disease (see Figure 60-2). Bilateral bone marrow aspirates and biopsies are performed to detect marrow involvement. Functional imaging such as FDG (fluorodeoxy-D-glucose) positron emission tomography is being increasingly used in the staging and follow-up of patients with ESFT.

Bacci G, Bertoni F, Longhi A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-grade central osteosarcoma of the extremity. Histologic response to preoperative chemotherapy correlates with histologic subtype of the tumor. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3068-3075.

Bernstein M, Kovar H, Paulussen M, et al. Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: Ewing sarcoma of bone and soft tissue and the peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1002-1032.

de Alava E, Gerald WL. Molecular biology of the Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor family. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):204-213.

Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):694-701.

Gurney JG, Swensen AR, Bulterys M. Malignant bone tumors. NIH Pub. No 99-4649. Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al, editors. Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, 1999.

Link ML, Gebhardt MC, Meyers PA. Osteosarcoma. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1074-1115.

Mirabello L, Troisi RJ Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer. 2009;115(7):1531-1543.