Chapter 15 Bone Grafting around an Articular Joint

Introduction

The contribution of stem cells in the graft is thought to be small, but the scaffold of bone and its contained growth factors is ideal for the formation of new bone. William Macewen of Glasgow proved the ability of bone graft to regenerate a humerus, and this followed an exemplary series of studies and research.1

The early hematoma forming around an injured bone surface (whether the result of your osteotomy or a fracture) immediately contains stem cells.2 These multiply rapidly in the hematoma and are in the right place to contribute to healing.

The osteoblasts are particularly sensitive to the mechanical environment.

Stability is defined as the maintenance of reduction and correlates with strength. Stiffness is a distinctly different parameter from strength and in fracture or osteotomy fixation is defined as the rigidity of the construct.

Flexible fixation and early cyclic movements are appropriate for the bulky callus formation needed in diaphyseal fractures.3

This external callus is rarely needed in the metaphysic or epiphysis where there is sufficient bulk and well vascularized cancellous bone that will allow rapid union. John Charnley took biopsies at 6 weeks following knee arthrodesis to prove that union is achieved in this time.4

Taking Autograft

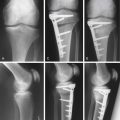

Cancellous Graft

When possible, a small sandbag behind the hip is useful.

Cut the fibers of gluteus maximus as they arise from the lip of the iliac crest.

Hemostasis will be needed at the posterior part of your incision.

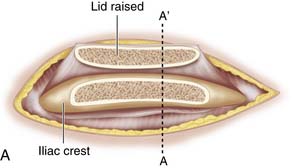

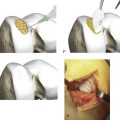

Use a saw to cut the outer table of the iliac crest and then a broad osteotome to lift a lid. This exposes the cancellous layer (see Fig. 15-1, A-C).

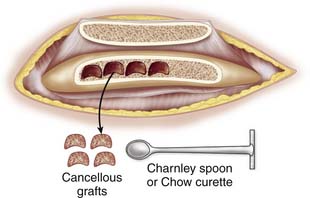

Use a sharp, long-handled curette to remove cancellous bone from between the cortical sheets (Fig. 15-2).

Keep the hematoma that gathers in the wound with your graft.

Corticocancellous Strips

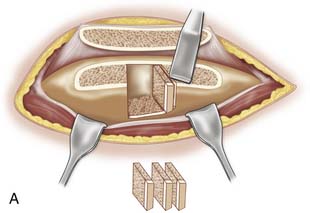

Expose the iliac crest as explained earlier. Use the saw to make an initial vertical cut, and then use a narrow and thin osteotome or chisel to cut thin vertical strips. A hammer is actually safer for controlling the instrument, as it avoids plunging that can occur if an osteotome is pushed by hand (see Fig. 15-3, A-B). The saw can also be used to cut the strips.

Tricortical Graft

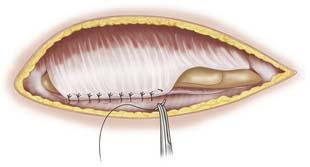

Expose the iliac crest as descried, and then strip all periosteum from the bone to be taken; otherwise it will not expand in the months and years following incorporation. Macewen described periosteum as the limiting membrane of bone. He undertook many studies on bone and was the first person to use allograft successfully.1

Percutaneous Techniques

Small amounts of graft are taken most conveniently and with less postoperative pain using systems such as the Precision Bone Grafting System (Kaltee Pty Ltd, Edwardstown, SA, Australia) (see Fig. 15-5). A small incision is made over the iliac crest 2 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine. A trocar and cannula is provided as means of excluding soft tissues.5

Figure 15-5 The Precision Bone Grafting System allows a percutaneous collection of small grafts. The cannula protects surrounding muscle and a circular handle (not shown) allows the graft to be cut. The blunt trocars provide a means of removing the plugs of graft. Made by Kaltec, www.kaltec.com.au.

Rotatory movements of the mill will allow the device to advance and graft to be obtained.

Allograft: Fresh Frozen

Allograft bone will carry a small risk of infection, despite all the screening measures used. All nonautologous graft does, however, carry the advantages of avoiding the complications of an autologous graft.6

Femoral Heads

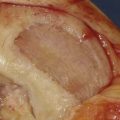

Wash away as much fat as possible with a power washer.

Allograft chips can be produced for impaction grafting using a mill for this purpose.

A polythene cutting block is better than a wooden one and available from kitchen shops.

A polyethylene jug with the base cut out is useful for preventing loss of these chips while working on the femoral head.

Excellent long-term results are seen either with allograft or with synthetic hydroxyapatite graft.7

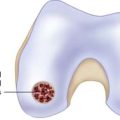

Autogenous Osteochondral Grafts

Bone can be replaced, as well as overlying cartilage loss, with these techniques.

Allograft: Osteochondral Graft

Those grafts require careful harvesting and regulatory control. It is possible to keep 67% of cells alive for 44 days if the graft is kept sterile.8 Alternatives include freezing of the graft in sequential steps with increasing concentrations of antifreezing agents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). This provides greater flexibility in timing of procedures and can also maintain a high proportion of viable chondrocytes. Close liaison with a tissue bank is necessary for these options.

Bone Graft Substitutes

These are numerous in composition, and handling has greatly improved. Table 15-1 lists only a selection.

| Demineralized Bone Matrix | Grafton, Allomatrix |

|---|---|

| rhBMP-2 | OP-1 Implant |

| rhBMP-2 | INFUSE |

| β-tri-calcium phosphate (TCP) | Allogran-R |

| Calcium sulphate | Stimulan |

| Hydroxyapatite | Actifuse, Allogran-N |

| Bi-phasic calcium based ceramics | geneX |

| Bioglass | Vitoss, NovaBone |

We use Allogran-N for load bearing in impaction grafting,7 geneX for tibial, and femoral tensegrity osteotomies,9 and for cultured stem cells in nonunion.10 Stimulan is used with added antibiotic for chronic osteomyelitis.

1. Macewen W. The growth of bone. Observations on osteogenesis. An experimental inquiry into the development and reproduction of diaphyseal bone. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons; 1912.

2. Oe K., Miwa M., Sakai, Lee S.Y., Kuroda R., Kurosaka M. An in vitro study demonstrating that haematomas found at the site of human fractures contain progenitor cells with multilineage capacity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Jan;89-B(1):133-138.

3. Kenwright J., Richardson J.B., Goodship A.E., et al. Effect of controlled axial micromovement on healing of tinial fractures. Lancet. 1986 Nov 22;2(8517):1185-1187.

4. Charnley J., Baker S.L. Compression arthrodesis of the knee; a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1952 May;34-B(2):187-199.

5. Website: www.kaltec.com.au/Precision Bone Grafting Kit.

6. Younger E.M., Chapman M.W. Morbidity at bone graft donor sites. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3(3):192-195.

7. Aulakh T.S., Jayasekera N., Kuiper J.H., Richardson J.B. Long-term clinical outcomes following the use of synthetic hydroxyapatite and bone graft in impaction in revision hip. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1732-1738.

8. Pearsall A.W.I.V., Tucker J.A., Hester R.B., Heitman R.J. Chondrocyte Viability in refrigerated osteochondral allografts used for transplantation within the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2004 Jan-Feb;32(1):125-131.

9. Richardson JB, Cooper JJ, Waters R D. Tensegrity Osteotomy System US Patent 2007/0233145.

10. Bajada S., Harrison P.E., Ashton B.A., Cassar-Pullicino V.N., Ashammakhi N., Richardson J.B. Successful treatment of refractory tibial non-union using calcium sulphate and bone marrow stromal cell implantation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(10):1382-1386.