Bone diseases of radiological importance

Introduction

Using the atlas approach adopted in Chapter 24, an example of each of the conditions is shown together with a summary of the main radiographic features seen in the skull and facial skeleton. It is worth remembering that bone is a constantly changing, dynamic tissue. Thus diseases of bone can present a spectrum of radiographic appearances depending on the behaviour and maturity or stage of the disease and/or lesion(s). The examples shown represent only a small part of that spectrum.

Developmental or genetic disorders

Cleidocranial dysplasia

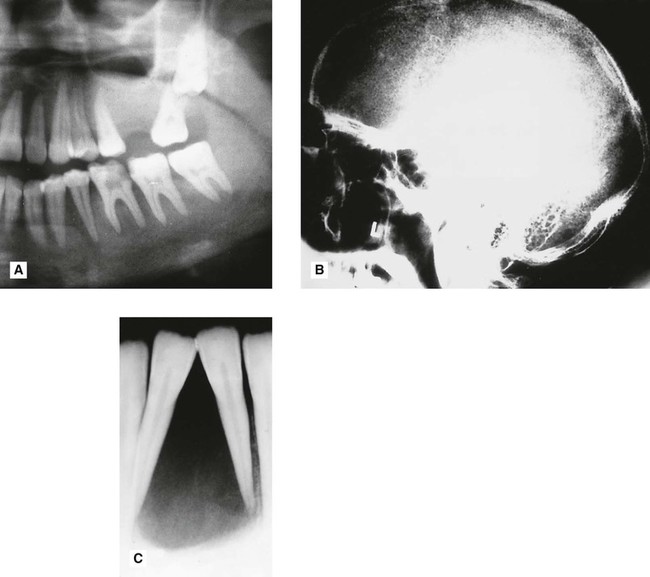

This is a rare developmental disturbance affecting the skull and clavicles. The abnormalities of dentition can be gross but usually affect only the permanent teeth. Examples are delayed eruption and multiple supernumeraries (see Fig. 28.1).

Osteopetrosis (Albers–Schönberg disease)

This hereditary disease is characterized by sclerosis of the skeleton (so called marble bones), fragile bones and secondary anaemia. Bone formation is normal but bone resorption is reduced, resulting in the presence of excessive calcified tissue and lack of marrow space (see Fig. 28.2). Cranial base changes may produce compression of the cranial nerves.

Main radiographic features

Infective or inflammatory conditions

Osteomyelitis

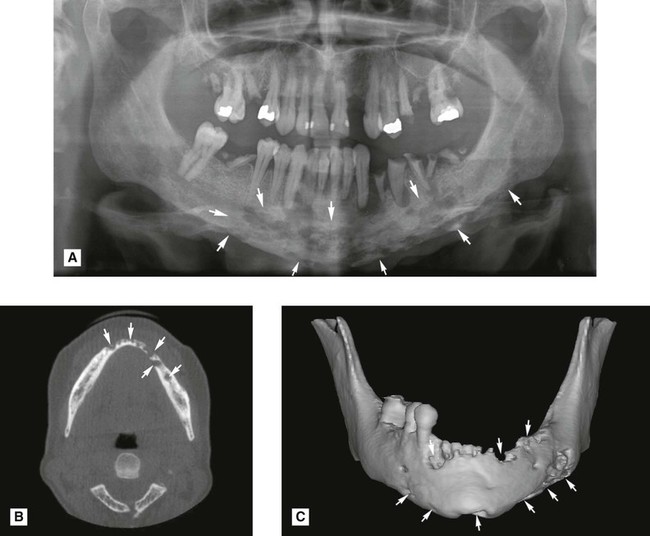

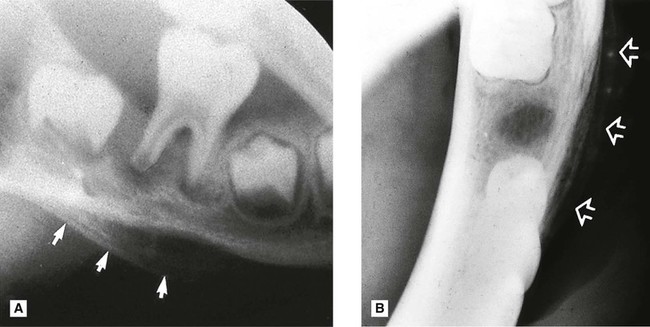

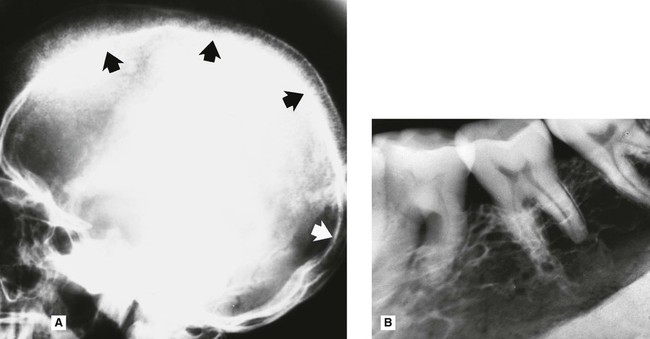

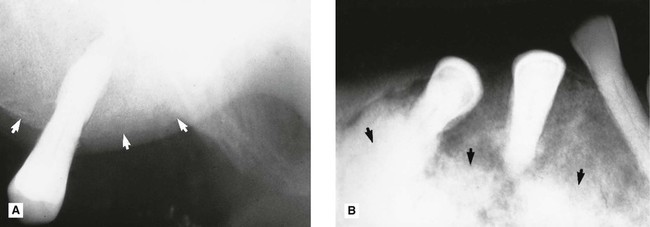

This spreading, progressive inflammation of bone and bone marrow, more frequently affects the mandible than the maxilla. It is caused usually by local factors such as periapical infection, pericoronitis, acute periodontal lesions, extractions or trauma. The inflammatory response may be acute or chronic depending on the virulence of the infecting organism and the resistance of the patient. It results ultimately in the destruction of the infected bone (see Figs 28.3 and 28.4). The reaction of the surrounding bone and periosteum is very variable and often age-related. There may be surrounding sclerosis of the bone forming poorly defined patchy opacity. Sequestra (small pieces of necrotic bone) can be exfoliated over a period of several weeks. The periosteum around the affected area can lay down new bone (the so-called periosteal reaction). In children this can be pronounced and is described as proliferative periostitis. This typically affects the mandible in young girls, following apical or pericoronal infection associated with the lower first molar producing a non-tender, bony hard swelling of the lower border. Radiographically the proliferative periostitis results in a laminated, so called onion-skin, appearance (see Fig. 28.5).

Main radiographic features of acute osteomyelitis

• Ragged, patchy or moth-eaten areas of radiolucency – the outline of the area of destruction is irregular and poorly defined

• Evidence of small radiopaque sequestra of dead bone occasionally within the radiolucency

• Evidence of new subperiosteal bone formation, usually beyond the area of necrosis, particularly along the lower border of the mandible.

Main radiographic features of chronic osteomyelitis

• Localized patchy or moth-eaten areas of bone destruction

• Sclerosis of the surrounding bone

• Evidence of small radiopaque sequestra of dead bone sometimes within the area of bone destruction

• Evidence of an involucrum surrounding the area of destruction following extensive subperiosteal bone formation.

Note: The radiographic appearance of osteomyelitis varies considerably depending on the type of underlying inflammatory response and the age of the patient.

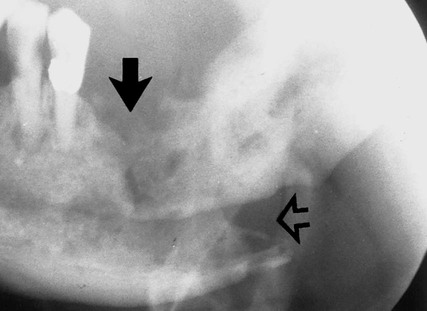

Osteoradionecrosis

The high doses of radiation used in radiotherapy reduce drastically the vascularity and reparative powers of bone. The mandible is particularly susceptible. Subsequent trauma (e.g. tooth extraction) or infection may produce osteomyelitis with rapid destruction of the irradiated bone, sequestra formation and poor healing. Radiographically, osteoradionecrosis resembles other types of osteomyelitis, although the border between necrotic and normal bone may be more sharply defined and subperiosteal new bone formation is not usually evident (see Fig. 28.6). A history of radiotherapy enables the differential diagnosis to be made.

Hormone-related diseases

Hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism, caused by either hyperplasia or an adenoma of the parathyroids, or secondary hyperparathyroidism caused by kidney disease, results in increased secretion of parathormone. This causes generalized skeletal bone resorption leading to osteopenia (generalized decrease in bone density), bone pain or even pathological fracture and raises the plasma calcium levels (see Fig. 28.8). Localized cyst-like central giant cell lesions (brown tumours) can also develop in the jaws and long bones. The term osteitis fibrosa cystica is used to describe severe chronic skeletal hyperparathyroidism following brown tumour degeneration and fibrosis.

Main radiographic features

• Evidence in the skull vault of osteopenia producing a fine overall stippled pattern to the bone – hence the description pepper-pot skull

– Osteopenia (in mandible and maxilla) producing a very fine trabecular pattern, often described as ground glass

– Loss of the lamina dura surrounding all the teeth and thinning or loss of the normal thick cortical bone of the lower border of the mandible

– Occasional localized radiolucent cyst-like central giant cell lesions (brown tumours, see Ch. 26)

Acromegaly

This is a disturbance of bone growth caused by hypersecretion of growth hormone (GH) usually as the result of a pituitary adenoma developing after puberty. Characteristic features include renewed growth of certain bones, particularly the jaws, hands and feet, and overgrowth of some soft tissues (see Fig. 28.9).

Main radiographic features

– Enlargement of the mandible; the length of the horizontal and ascending rami are both increased causing it to become prognathic with an increased obliquity of the angle and with loss of the antegonial notch

– The body of the mandible may also be bent or bowed downwards anterior to the angle

– Enlargement of the inferior dental canal

– Thickening and enlargement of the alveolar bone with spacing and fanning out of the teeth, particularly anteriorly, resulting in an open bite.

Blood dyscrasias

Sickle cell anaemia

• Increased production of red blood cells and hyperplasia of the bone marrow at the expense of the cancellous bone

Main radiographic features

• Evidence in the skull vault of:

– Thickening of the frontal and parietal bones

– Widening of the diploic space

– A generalized coarse trabecular pattern, fewer trabeculae are evident and the spaces between them appear larger

– The remaining trabeculae between the roots of the teeth can become aligned horizontally to produce a step ladder appearance

– Enlargement of the maxillae, with protrusion and separation of the upper anterior teeth

Thalassaemia (Cooley’s anaemia)

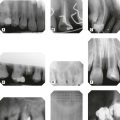

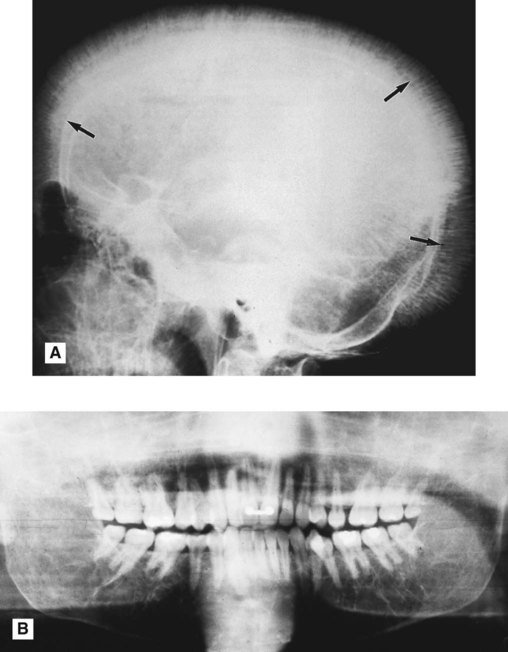

This hereditary haemoglobinopathy is characterized by chronic haemolytic anaemia and mainly affects people from the Mediterranean area. The defect lies in an inability to make enough normal globin chains, thus creating abnormal red blood cells which have a shortened life expectancy. Again the radiographic features result from the bone marrow proliferation required to produce more red blood cells with subsequent remodelling of all affected bones (see Fig. 28.11).

Main radiographic features

• Evidence in the skull vault of:

– Widening of the diploic space

– Thinning of the inner and outer tables

– Remodelling of the trabeculae to give sparse lines which may radiate outwards from the inner table producing the hair-on-end appearance

– Generalized coarse trabecular pattern with very large marrow spaces

– Expansion, which may lead to encroachment on, and subsequent obliteration of the maxillary antra

– Thinning of all cortical structures, most noticeably the lower border of the mandible

Diseases of unknown cause

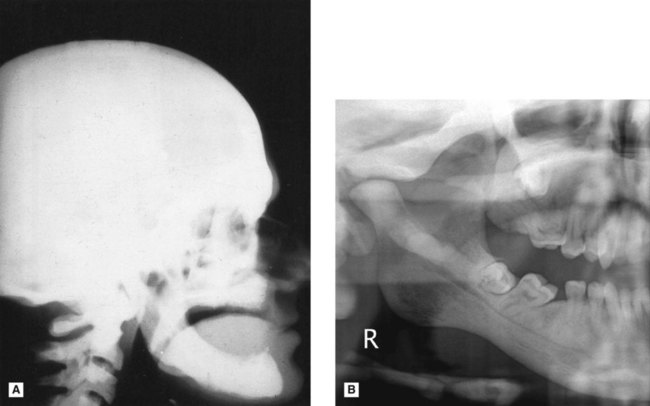

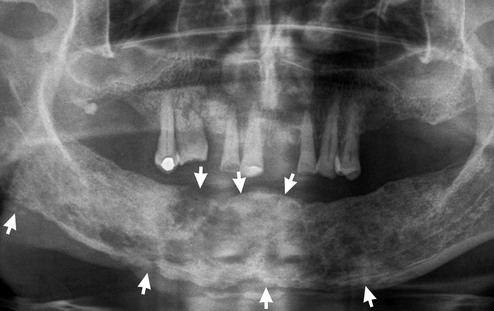

Fibrous dysplasia

As mentioned in Chapter 27, fibrous dysplasia is categorized as a bone-related lesion in the WHO 2005 Classification. It is described by the WHO as a genetically based sporadic disease of bone affecting single or multiple bones. It usually develops in childhood and is manifest before the age of ten. It is characterized by the proliferation of fibrous tissue and resorption of normal bone in one or more localized areas, and subsequent replacement with poorly formed, haphazardly arranged, new bony trabeculae. Clinical varieties include:

• Monostotic fibrous dysplasia, characterized by a lesion affecting a single bone, including the jaws, particularly the posterior part of the maxilla (see Figs 28.12 and 28.13).

• Polystotic fibrous dysplasia, characterized by multiple bone lesions and subdivided into:

Main radiographic features of monostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting the jaws

• A localized rounded zone of relative radiolucency containing a variety of fine trabecular patterns, described as ground glass, fingerprint and orange peel. The more mature the lesion the more radiopaque it appears

• Poor definition of the edge of the lesion which merges imperceptibly with the surrounding normal bone (see Fig. 27.18).

• Loss of the lamina dura with thinning of the periodontal ligament shadow

• Enlargement of the affected bone

• In the maxilla encroachment on, or obliteration of, the antrum and spread into particularly the zygoma and sphenoid bones of the cranial base

• Associated teeth occasionally displaced, but rarely resorbed.

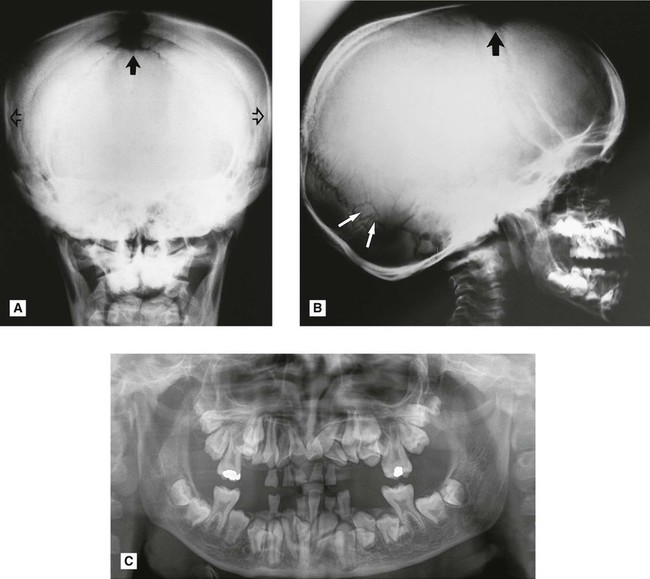

Paget’s disease of bone (osteitis deformans)

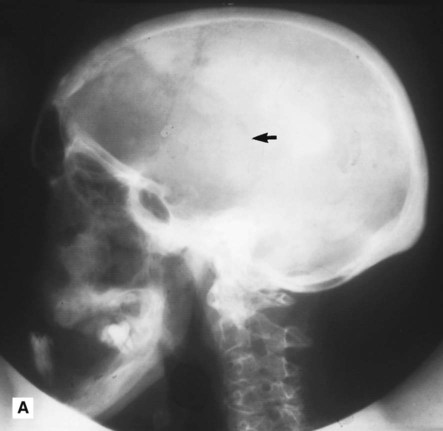

In this disease of the elderly, the normal processes of bone deposition and resorption are disturbed severely, but only in certain bones and usually symmetrically. The main features are an enlarged head and thickening of the affected long bones, which bend under stress. Typically the early stages of the disease are characterized by bone resorption and the later stages by bone deposition, although there is no clear-cut distinction between the two stages (see Figs 28.14 and 28.15).

Main radiographic features of early-stage Paget’s disease of bone

Main radiographic features of late-stage Paget’s disease of bone

• Evidence in the skull vault of:

– Haphazard deposition of sclerotic bone in the earlier zones of osteoporosis producing an appearance resembling cottonwool patches

– Enlargement and distortion of the shape of the skull including basilar invagination

To access the self assessment questions for this chapter please go to www.whaitesessentialsdentalradiography.com

, showing the typical destructive appearance (solid arrow), which has resulted in a pathological fracture (open arrow). Radiotherapy had been given several years previously.

, showing the typical destructive appearance (solid arrow), which has resulted in a pathological fracture (open arrow). Radiotherapy had been given several years previously.

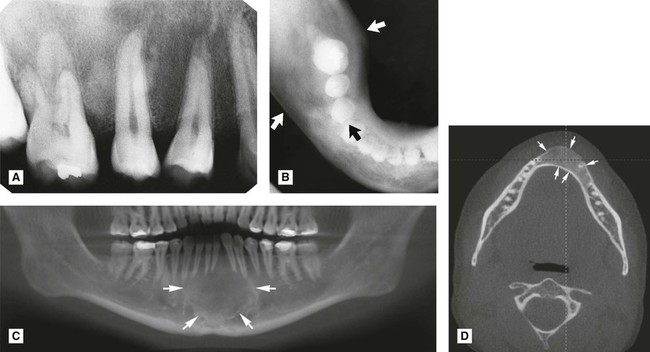

. B Lower 90° occlusal centred on the right side, again showing the ground glass appearance and expansion but involving the mandible in the premolar and molar regions (arrowed). The anterior part of the mandible is unaffected. C Reconstructed CBCT panoramic showing the ground glass appearance in the anterior mandible (arrowed). Note how the edges of the lesion merge imperceptibly with the surrounding normal bone. D Axial CBCT showing the expansion of the anterior part of the mandible (arrowed).

. B Lower 90° occlusal centred on the right side, again showing the ground glass appearance and expansion but involving the mandible in the premolar and molar regions (arrowed). The anterior part of the mandible is unaffected. C Reconstructed CBCT panoramic showing the ground glass appearance in the anterior mandible (arrowed). Note how the edges of the lesion merge imperceptibly with the surrounding normal bone. D Axial CBCT showing the expansion of the anterior part of the mandible (arrowed).

/>

/> />

/>