Bone disease

Bone metabolism

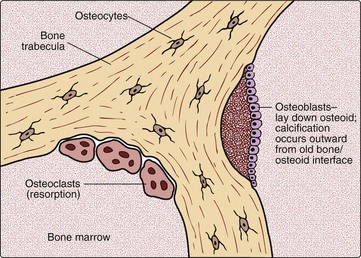

Bone is constantly being broken down and reformed in the process of bone remodelling (Fig 38.1). The clinician looking after patients with bone disease will certainly need to know to what extent bone is being broken down, and, indeed, if new bone is being made. Biochemical markers of bone resorption and bone formation can be useful in assessing the extent of disease, as well as monitoring treatment.

Common bone disorders

Osteomalacia and rickets

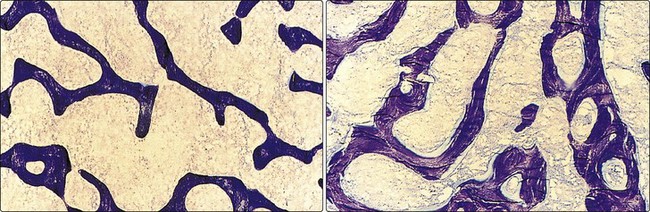

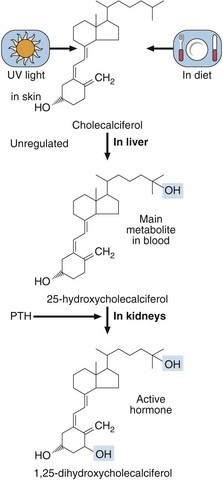

Osteomalacia is the name given to defective bone mineralization in adults (Fig 38.2). Rickets is characterized by defects of bone and cartilage mineralization in children. Vitamin D deficiency was once the most common reason for rickets and osteomalacia, but the addition of vitamin D to foodstuffs has reduced the condition except in the elderly or house-bound, the institutionalized, and in certain ethnic groups. Although elderly Asian women with a predominantly vegetarian diet are particularly at risk, it should be noted that there appears to be a resurgence of rickets and osteomalacia in the white population of lower socio-economic status, due to poor diet and limited exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D status can be assessed by measurement of the main circulating metabolite, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, in a serum specimen. The metabolism of vitamin D is shown in Figure 38.3.

The bony features of osteomalacia and rickets are also shared by other bone diseases (see later).

Other bone diseases

Vitamin-D-dependent rickets, types 1 and 2. These are rare bone diseases resulting from genetic disorders leading to the inability to make the active vitamin D metabolite, or from receptor defects that do not allow the hormone to act.

Vitamin-D-dependent rickets, types 1 and 2. These are rare bone diseases resulting from genetic disorders leading to the inability to make the active vitamin D metabolite, or from receptor defects that do not allow the hormone to act.

Tumoral calcinosis. This is characterized by ectopic calcification around the joints.

Tumoral calcinosis. This is characterized by ectopic calcification around the joints.

Hypophosphatasia. This is a form of rickets or osteomalacia that results from a deficiency of alkaline phosphatase.

Hypophosphatasia. This is a form of rickets or osteomalacia that results from a deficiency of alkaline phosphatase.

Hypophosphataemic rickets. This is believed to be a consequence of a renal tubular defect in phosphate handling.

Hypophosphataemic rickets. This is believed to be a consequence of a renal tubular defect in phosphate handling.

Osteopetrosis. This condition is characterized by defective bone resorption.

Osteopetrosis. This condition is characterized by defective bone resorption.

Osteogenesis imperfecta. Brittle bone syndrome is an inherited disorder which occurs around once in every 20 000 births.

Osteogenesis imperfecta. Brittle bone syndrome is an inherited disorder which occurs around once in every 20 000 births.

Diagnosis of these and other rare conditions may require help from specialized laboratories.

Biochemistry testing in calcium disorders or bone disease

Characteristic biochemistry profiles in some common bone diseases are shown in Table 38.1.

Table 38.1

Biochemical profiles in bone diseases

| Disease | Profile |

| Bone metastases | Calcium may be high, low or normal |

| Phosphate may be high, low or normal | |

| PTH is usually low | |

| Alkaline phosphatase may be elevated or normal | |

| Osteomalacia/rickets | Calcium will tend to be low, or may be clearly decreased |

| PTH will be elevated | |

| 25-hydroxycholecalciferol will be decreased if the disease is due to vitamin D deficiency | |

| Paget’s disease | Calcium is normal |

| Alkaline phosphatase is grossly elevated | |

| Osteoporosis | Biochemistry is unremarkable |

| Renal osteodystrophy | Calcium is decreased |

| PTH is very high | |

| Osteitis fibrosa cystica (primary hyperparathyroidism) | Calcium is elevated Phosphate is low or normal PTH is increased, or clearly detectable and thus ‘inappropriate’ to the hypercalcaemia |