Chapter 18. Bone and joint infections

Acute osteomyelitis

Bone infection usually involves the bone marrow and is therefore called osteomyelitis. The disease can be acute or chronic.

Acute osteomyelitis is seen in both children and adults. In days past it was a common cause of disease and death but in the last 50 years it has become both less common and less serious.

Pathology

The disease begins with an infection in the juxta-epiphyseal region of the bone. The symptoms often begin after minor trauma, perhaps because the trauma creates a small haematoma from rupture of the very profuse blood vessels near the epiphyseal plate. The haematoma provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria reaching it from the bloodstream.

Clinical features

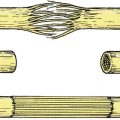

As the infection proceeds, the patient becomes ill and pyrexial and develops excruciating pain because of the tissue tension within the bone. Untreated, the infection spreads until it erodes the surrounding bone and eventually the cortex, allowing pus to strip the periosteum off the bone, and forms a subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 18.1). The pus will eventually discharge through the skin, leaving a bone abscess discharging through a sinus. At this stage the patient has chronic osteomyelitis.

|

| Fig. 18.1

Progress of osteomyelitis: (a) small septic focus next to the epiphyseal plate; (b) collection of pus beneath the periosteum; (c) pus has drained through the skin and an abscess cavity in the bone communicates with skin.

|

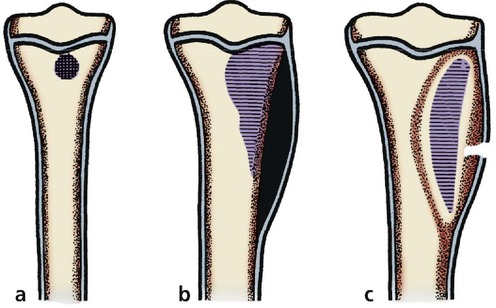

If the epiphyseal plate lies inside a joint the pus will discharge not through skin but into the joint, causing a septic arthritis. The following joints can become infected in this way (Fig. 18.2):

1. Hip.

2. Knee.

3. Shoulder.

4. Elbow.

5. Wrist.

|

| Fig. 18.2

Joints susceptible to septic arthritis.

|

Treatment

In the first few days of the disease, when there is a hot tender bone and a pyrexia, the child should be admitted to hospital, the limb elevated and blood sent to the laboratory for haemoglobin, ESR, white cell count and blood culture. Only when the blood culture specimens are safely in the laboratory should antibiotic therapy be given.

The antibiotics given should be the ‘best guess’ based on the prevalent organisms in the hospital and neighbourhood. A good microbiologist will know the most likely organism to cause bone infection in the area, but Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae are the usual culprits. A good antibiotic regimen is a combination of ampicillin 500 mg four times daily and flucloxacillin 500 mg four times daily, although 1 g four times daily may be needed.

If the patient is not clinically better after 2 days treatment and the pyrexia remains unchanged, the affected area of bone should be exposed and drilled to release pus.

Almost every patient with acute osteomyelitis can be cured in this way and chronic osteomyelitis has almost become a disease of the past in developed countries.

Brodie’s abscess. Not all osteomyelitis behaves in this way. The infection can be partly overcome by natural defences and remain confined in an abscess lined by cortical bone. These lesions, called Brodie’s abscesses, are visible radiologically as a small cavity and contain quiescent bacteria.

Chronic osteomyelitis

Chronic osteomyelitis, one of the grand old diseases of orthopaedic surgery a major cause of disability and crippling in the 19th century, is a complication of acute osteomyelitis in which the infection persists.

Pathology

Pus spreads under the periosteum around the cortex, which dies (Fig. 18.3). The periosteum then forms a ‘new’ bone around the abscess, leaving a mass of dead bone lying in a pocket of pus surrounded by living bone (Fig. 18.4). The dead bone, which is separate from the living and cannot be discharged from the body because it is too large to pass down the sinus, is called a sequestrum. The living bone surrounding it is the involucrum.

|

| Fig. 18.3

Late complications of bone and joint sepsis: ( A) involucrum, sequestrum and sinus; ( B) squamous carcinoma at the margin of the sinus; ( C) amyloid disease; ( D) ankylosed joint following septic arthritis; ( E) deformity from growth arrest.

|

|

| Fig. 18.4

(a) Chronic osteomyelitis of the radius; (b) chronic osteomyelitis of the humerus. The lesion has been drained with drill holes and windowing, but a large sequestrum of dead bone remains in the cavity of the involucrum.

|

Clinical features

Without treatment, the patient is left with a large bony cavity containing pus and dead bone, communicating with the exterior through a sinus that discharges stinking pus and occasional pieces of dead bone, and requires regular dressing (Fig. 18.5). Apart from the misery of such a condition, there are serious complications:

1. Growth changes follow damage to the epiphyseal growth plates (Fig. 18.6).

|

| Fig. 18.6

Late damage to the humeral epiphysis from sepsis.

|

|

| Fig. 18.5

A sinus from osteomyelitis which had been present for more than 20 years.

|

2. The chronic infection leads to secondary amyloid disease.

3. The skin margins can undergo malignant change (Marjolin’s ulcer).

Treatment

Today, many of the chronic sinuses can be healed by eradication of dead bone and correct antibiotic treatment. This sounds straightforward but, in some patients, to remove all the dead bone means excising a complete segment of bone, bridging the gap with external fixation, and grafting the defect when the infection has been eradicated. This is extensive surgery requiring prolonged admission to hospital and antibiotics must be given in adequate doses for long periods, sometimes for a year or more.

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis can arise in three ways:

1. Spread from an infected bone.

2. Direct infection from a penetrating wound.

3. Bacteraemia.

Clinical features

Septic arthritis should be suspected in any hot swollen joint, particularly if there is infection elsewhere or the patient is systemically ill.

Infected joints are extremely painful and the patient is systemically ill unless there is another debilitating condition, such as diabetes. This is an important exception because diabetic patients are particularly susceptible to infection. Any unexplained joint effusion in a diabetic should be aspirated and sent for culture.

Do not forget the gonococcus! The gonococcus has a special affinity for joints, hence its name, and should always be thought of when a young adult presents with septic arthritis.

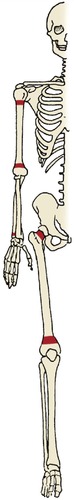

Untreated, septic arthritis destroys articular cartilage and leads to a bony ankylosis (Fig. 18.7). If the patient is fortunate, the joint becomes ankylosed in the position of function, but more often the patient holds the joint in the position of ease; i.e. the position in which it is least painful because the joint cavity is greatest. The joint then becomes fused in a position that is not ideal for normal use. Occasionally the ankylosis occurs with fibrous tissue instead of bone and an arthrodesis is needed to produce a better result.

|

| Fig. 18.7

Natural history of septic arthritis. Septic arthritis can lead to: (a) a normal joint; (b) fibrous ankylosis; (c) bony ankylosis.

|

Neonatal septicaemia

Neonatal septicaemia causes widespread septic arthritis (Fig. 18.8). Once common, and known as Tom Smith’s arthritis, the condition is now rare in developed countries but is sometimes seen after exchange transfusion and invasive procedures on the newborn.

|

| Fig. 18.8

Dislocation and loss of the femoral head following septic arthritis of the hip in infancy.

|

Treatment

Treatment depends on a thorough lavage of the joint and adequate antibiotic treatment. An irrigation–drainage system in which fluid is alternately run into the joint and drained out at hourly or 2-hourly intervals is usually effective if coupled with adequate antibiotic treatment. Thorough irrigation of the joint, if necessary combined with arthroscopy and division of intra-articular adhesions, will usually eradicate septic arthritis.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis of bone is still a scourge in undeveloped countries but rare elsewhere (Fig. 18.9). The course of the disease is similar to that of ordinary bone and joint infection, but in slow motion. The illness is chronic, the symptoms develop slowly, the pyrexia is less marked and the abscesses are slow to form. Joint tuberculosis is a disease of synovium and is so similar to rheumatoid arthritis in presentation that it was once thought they were the same condition.

|

| Fig. 18.9

Tuberculosis of the hip with rarefaction and bone destruction.

|

Treatment is similar to that of other infections but taken at a slower pace and with a different drug regimen. A combination of antibiotic drugs such as ethionamide, rifampicin, isoniazid (INH) and ethambutol is usually effective, provided that there is no dead bone within the abscess cavity.

Drugs for tuberculosis

1. Ethionamide.

2. Rifampicin.

3. INH.

4. Ethambutol.

The drugs should be given in combination.

Disc infection

The intervertebral discs can become infected with obscure organisms such as brucella, micrococci or fungi, producing severe back pain (p. 463). Providing the infecting organism can be correctly identified, antibiotics are usually effective, but exploration and spinal fusion is sometimes required.

In children, inflammation of the discs can occur in the absence of any detectable infection.

Syphilis

Syphilis of bone is rare in modern days, and the classic sabre tibia caused by syphilitic periostitis is seen more often in museums than orthopaedic clinics.

From an orthopaedic standpoint the most important aspect of syphilis is the Charcot neuropathic joint (p. 308). These joints are grossly unstable, insensitive and often look suitable for joint replacement or arthrodesis. They do badly and the temptation to operate must be resisted.