Chapter 21 Bodylifts and Post Massive Weight Loss Body Contouring

Summary

Introduction

There has been a tremendous surge in excisional body contouring procedures in recent years fueled by the growing obesity epidemic and the success of weight-loss surgery. In the USA, obesity is a major problem and its incidence is increasing worldwide.1–3 The potential benefits of substantial weight loss, most notably, a reduction in obesity-associated morbidity, such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis, has grabbed the attention of public health agencies. While medical weight-loss methods often prove difficult and ultimately unsustainable, bariatric surgical procedures are now recognized as a more reliable method of weight loss for morbidly obese patients.4–6 The demand for bariatric surgery is expected to rise as long as no alternative treatment for morbid obesity exists.7 As a result, the number of patients seeking surgery to remove or reposition redundant skin and tissues is expected to increase proportionally. Data from 2006 reveal that 65 000 massive weight loss (MWL) patients underwent body-contouring procedures.8 As the scope and magnitude of body contouring procedures increases each year, the plastic surgeon must pay close attention to issues of patient safety.

Evaluation of the Massive Weight Loss Body Contouring Patient

MWL patients often present with a variety of deformities, based on their initial body-fat distribution. While some may have a preponderance of truncal excess, others may exhibit significant lower-extremity deformities. An overall assessment of the patient should be made taking into account the distribution of the skin laxity, remaining adiposity, rolls, folds, skin tone, integrity, scars, abdominal-wall structure (rectus diastasis, hernias, thickness), and overall constitution (i.e. poor mobility, chronic pain, stigmata of malnutrition). With the patient standing in front of a mirror, the surgeon may demonstrate possible improvements that can be achieved with resection by manually pinching and repositioning tissues. Asymmetries should be noted to the patient and documented. Standardized photographs of the patient should be taken prior to surgery from multiple angles to document preoperative deformities. A surgical plan for patients with multiple contour irregularities must then be developed. The Pittsburgh Weight Loss Deformity Scale is a useful tool to help describe the deformities observed and help plan what procedures are needed for a given deformity.9

The key factor in optimizing results, limiting complications, and maximizing safety in the body-contouring population is patient selection. Patients typically present for body contouring at least 1 year after gastric bypass surgery and should be weight stable for at least 3 months. Their BMI should be favorable, with current literature suggesting that a BMI >35 may result in an increased risk of surgical complications.10,11 Patients with a BMI of >35 should generally lose more weight before obtaining surgery. Exceptions to this rule include a true giant disabling pannus or chronic panniculitis, conditions for which a functional panniculectomy would be indicated. A favorable BMI, however, does not always predict appropriate nutritional status and may not represent an ideal patient for body contouring. Medical and psychosocial issues should be fully evaluated and optimized. Patients should have realistic expectations and goals. Financial issues should also be taken into consideration, including allowing adequate time out of work for recovery. Many patients may be disappointed that they have not reached an appropriate BMI, nutritional status, or other preoperative criteria. Encouragement and reassurance can motivate them to work on these issues and follow-up for another consultation.

Hernias are common in patients who have had previous open abdominal surgery. Consideration should be given to planning a team case with the bariatric surgeons. Body-contouring operations can be performed at the same time as hernia repairs, however, the length of the body contouring procedures should take into consideration the magnitude of the hernia and potential operative time needed to repair the hernia appropriately.12 Patients presenting for hernia repair, or lower body lifts that require position changes, may benefit from preoperative bowel preparations, thereby decreasing risk of intraoperative contamination and postoperative discomfort.

Surgical Technique

Variations of abdominoplasty for the weight-loss patient

The abdomen is perhaps the area of most concern for patients who seek body contouring. While a thorough discussion of abdominoplasty is presented in Chapter 20, we will cover some variants of the procedure relevant to the MWL patient. As early as 1899 and again in 1910, Dr Kelly described his experience with the transverse resection of the pendulous abdomen.13 This work led to the modern abdominoplasty as we know it today,14,15 which has been largely considered to be a cosmetic operation. For the MWL patient, however, the abdominal pannus is often the source of functional problems, with difficulty ambulating or intertrigo. In this patient population, abdominal contouring has both cosmetic and functional components. The degree of cosmetic impact will depend primarily on the ability to perform additional undermining, plication, and umbilical transposition safely. In general, patients with a higher BMI and/or patients with higher medical risk will undergo a functional panniculectomy. In its simplest form, an elliptical excision of the pannus is performed with little or no undermining outside the area of resection. The umbilicus is usually sacrificed, and no plication is performed. At least two Jackson-Pratt drains are placed. The authors prefer a closure consisting of interrupted 2–0 polypropylene vertical mattress sutures with the knots placed superiorly. The sutures are spaced every 1–2 cm to ensure eversion of the wound edges and add strength to the closure, and skin staples are placed to approximate the skin edges. This closure technique has proven very secure, with a low rate of wound dehiscence. If there is active panniculitis, the staples are left out and gauze wicks are inserted between the mattress sutures. These are removed in 48 hours.

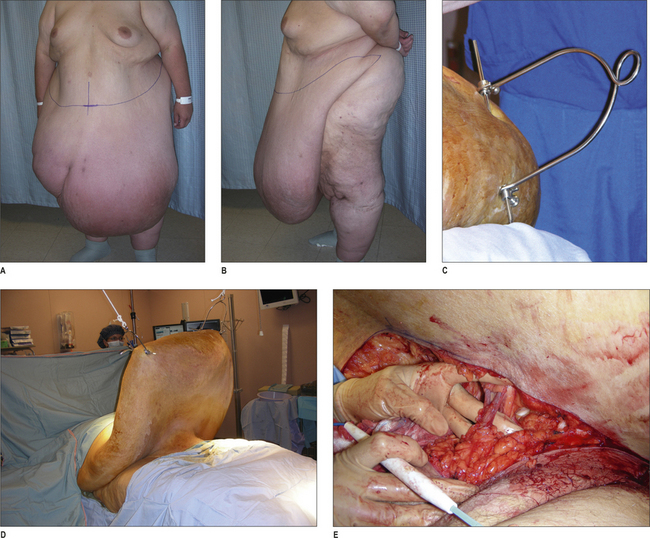

A variant of the functional panniculectomy is management of the ‘giant pannus’. This condition involves a pannus so large that ambulation and activities of daily living are severely hampered. A true giant pannus is not a very common entity, and is most often seen in patients who start the bariatric surgery process at an extremely high BMI and, despite significant weight loss, may still have a BMI that is in the severely obese range. While most severely obese patients are best treated with panniculectomy when their BMI is much lower, the functional impairment of the giant pannus can warrant the risk of surgery. To facilitate the operation, the pannus is suspended from ceiling bars or hydrolic lift using orthopedic pins and traction bows (Fig. 21.1). This allows venous blood to drain from the pannus prior to the procedure, prevents the pannus from resting on the patient’s chest during the procedure (which can impair ventilation), and enables better exposure and control of the impressively large blood vessels that will be encoun-tered. The wound closure is as described above for the functional panniculectomy.

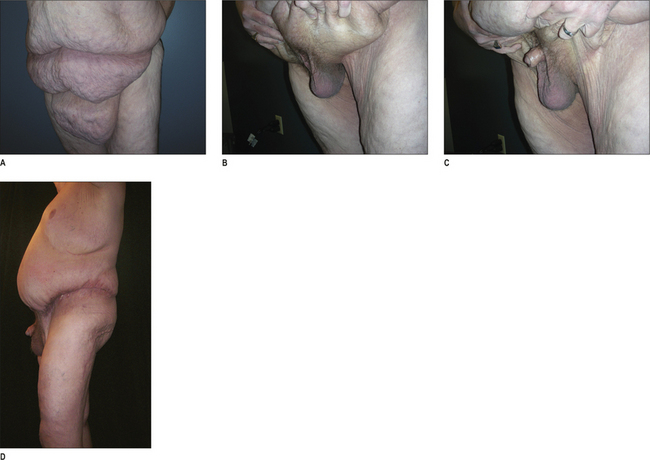

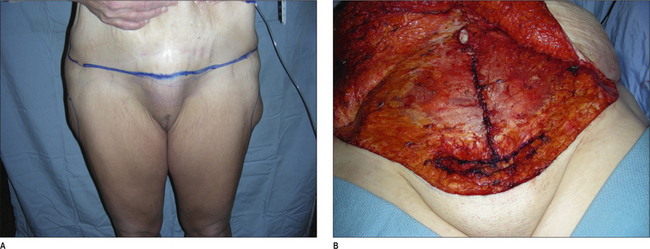

Another variant of the functional panniculectomy is correction of the buried penis (Fig. 21.2). In this syndrome, the penis is invaginated within the pannus. It may be possible to manually extract the penis, or there may be a tight cicatrix on the pannus that prevents this maneuver. In the latter case, it is useful to have an urologist available when the scar tissue is released in case there is unexpected pathology and/or difficulty releasing the contracted penis and scrotum. Once the penis is manually extracted from within the pannus, the panniculectomy can be commenced superior to the genital region. It is usually necessary to secure the tissues above the genital region to the abdominal wall in a manner similar to the mons-plasty described below.

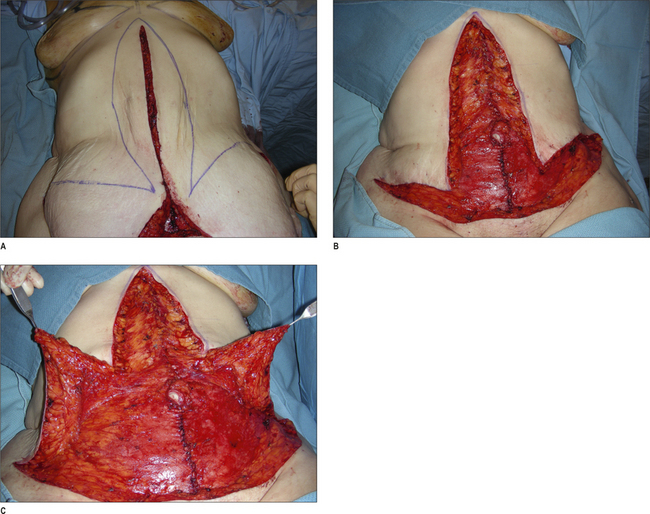

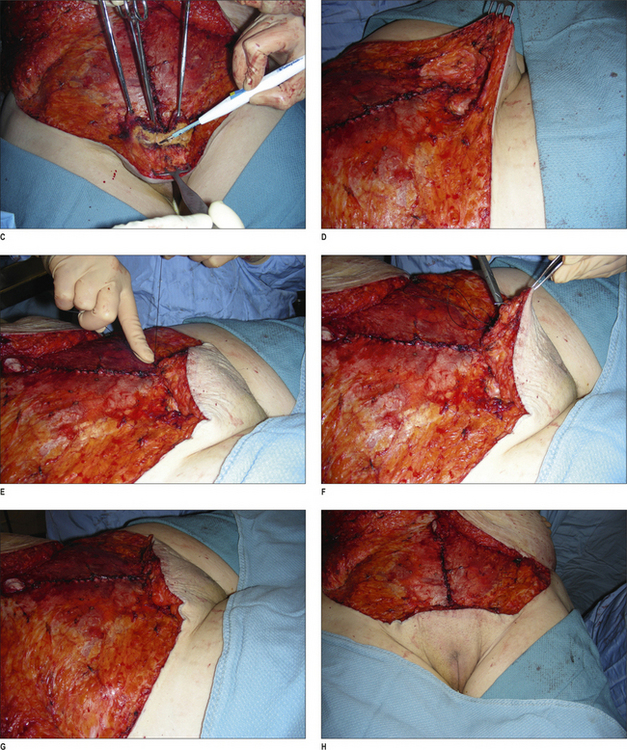

An evolution of the abdominoplasty procedure includes the addition of a vertical scar to eliminate horizontal excess, which is often necessary in the MWL patient.16,17 Patients with significant epigastric skin excess are willing to accept a new vertical midline scar in exchange for improved contour. Although a less desirable approach, patients reluctant to commit to the vertical scar can still have the vertical resection done in a second stage if they are not satisfied with the results of a transverse only abdominoplasty. The key to performing this procedure safely is to limit undermining of the tissues outside of the area of resection (Figs 21.3–21.5). Specifically, the authors advocate not undermining to the costal margin. We have found that preservation of these perforating vessels in the upper abdomen will decrease the risk of wound complications. Patients are advised that there is a higher risk of wound-healing problems compared with a standard abdominoplasty. Additionally, great care is taken to avoid excessive tension on the ‘triple point’, or confluence of scars on the lower abdomen. This is best accomplished by first resecting tissue in a horizontal axis as with the standard abdominoplasty procedure. The horizontal wound is then approximated with sharp towel clips. Next, the vertical resection is marked with the transverse wound approximated. When insetting the umbilicus in a vertical abdominoplasty incision, minimal if any cutout should be created for the umbilicus. With lateral tension and time, this will naturally widen to good shape. If a circular incision is made at the site of the umbilicus inset at the time of initial operation, this will widen to an undesirable horizontally elongated shape.

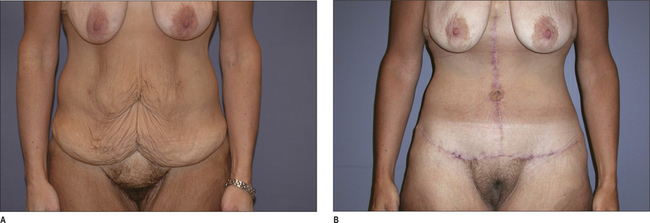

Monsplasty

Correction of mons ptosis and fullness is a necessary adjunct to abdominal contouring in a high percentage of MWL patients. The mons can be thinned to match the upper abdominal flap and elevated using suture to restore a youthful contour. Failure to correct the mons during an abdominoplasty or lower body lift can lead to an unsatisfactory result, despite adequate correction of the abdomen, thighs, or buttocks. During the abdominal-contouring procedure, the incision for the lower margin of resection should be placed 6 cm above the anterior vulvar commissure with the tissues on upward stretch (the line of incision should come just above the pubic symphysis, and may need to be marked slightly higher than 6 cm). This will help restore the proper proportions for the pubic hairline. In order to properly reshape this region, two specific steps are contemplated. One consideration is for the suspension of tissues to the abdominal fascia. The second consideration is reduction of the thickness of the mons. The authors have found that liposuction, when used to thin the tissue of the mons, results in prolonged edema and an unpredictable result. We have had good success with direct defatting of the tissue of the mons. The thickness of adipose tissue to be resected is estimated and marked. This is based on the thickness of the abdominal flap in relation to the desired thickness of the mons region. Next, the deep adipose tissue is retracted with three Allis clamps and skin retractors placed on the anterior surface. Using the electric cautery, a wedge resection of the adipose tissue is performed with the dissection terminated at the pubic symphysis. Great care is taken to avoid entering the vaginal vault. This technique results in a uniform thinning of the mons region. With or without this initial reduction in thickness, the mons can then be suspended to the abdominal wall fascia. Three to five sutures are placed from the deep layers of the mons superficial fascial system (SFS) into the abdominal wall fascia using either 2–0 or 0-braided nylon. This technique has resulted in durable results with a high degree of patient satisfaction (Figs 21.6 & 21.7). We have encountered no incidences of sexual dysfunction; quite the opposite in fact, patients are so pleased to have this region rejuvenated that they report an improvement in their sexual function. Patients are warned that the angle of the urine stream may be changed temporarily because of the pull on the mons tissues.

Lower-body lift

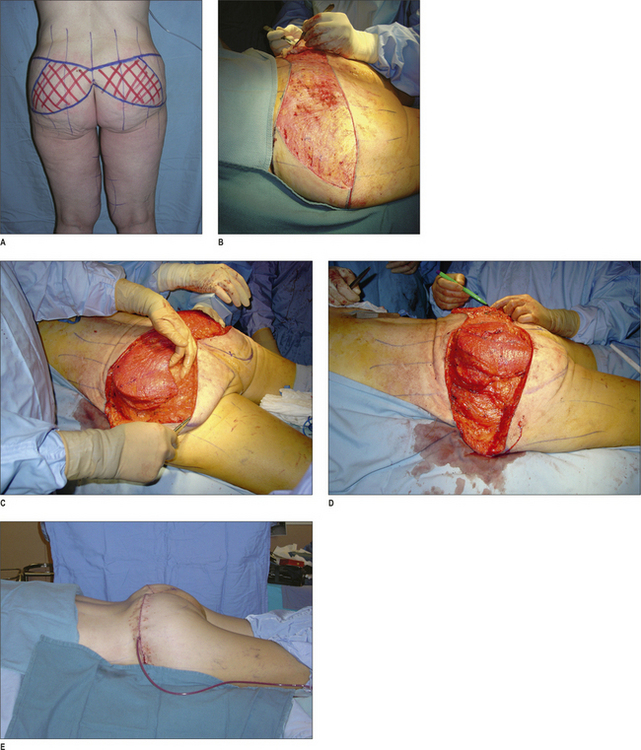

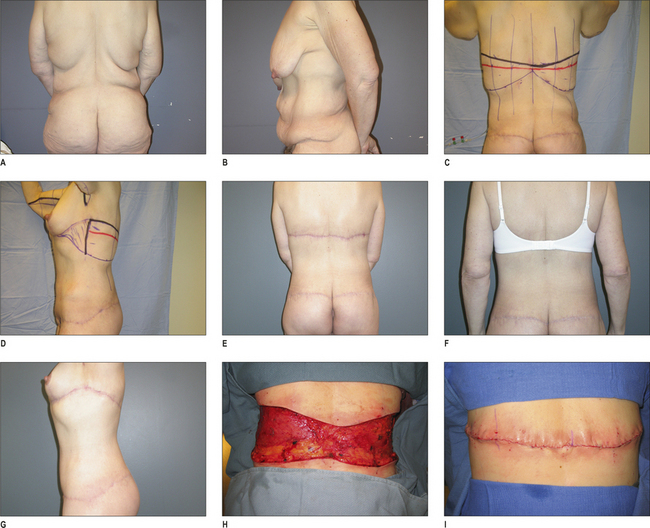

Correction of the abdomen alone is often not enough to restore appropriate contour for many MWL patients. Procedures have been devised to correct the entire lower-body unit, including the lower-body lift, belt lipectomy, and circumferential torsoplasty.18–21 Although the names are different, the principle in theory is similar; to affect a circumferential correction of laxity in the buttocks, lateral thighs, and abdomen with elimination of rolls and festoons.22 Lockwood popularized the lower-body lift, and made many important contributions to this field including the repair of the superficial fascial system.23 Further enhancements of outcomes have resulted from autologous augmentation of the buttocks with lower-body lift procedures.24,25 Fat can be preserved from the posterior resection based on gluteal artery perforators, deepithelialized, and rotated into pockets over the gluteal muscles to give shape to a region that otherwise becomes flattened with routine lift procedures. For the abdomen, the fleur-de-lis can be added concomitantly if laxity remains in the horizontal vector.

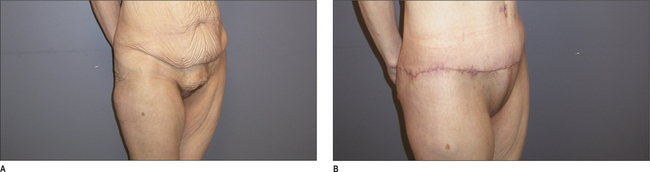

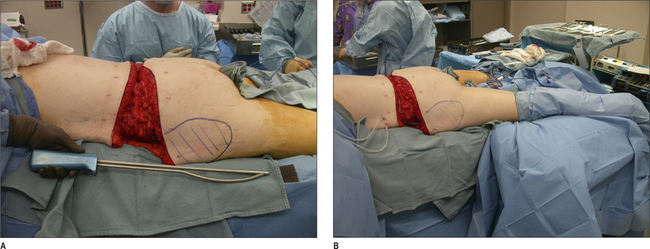

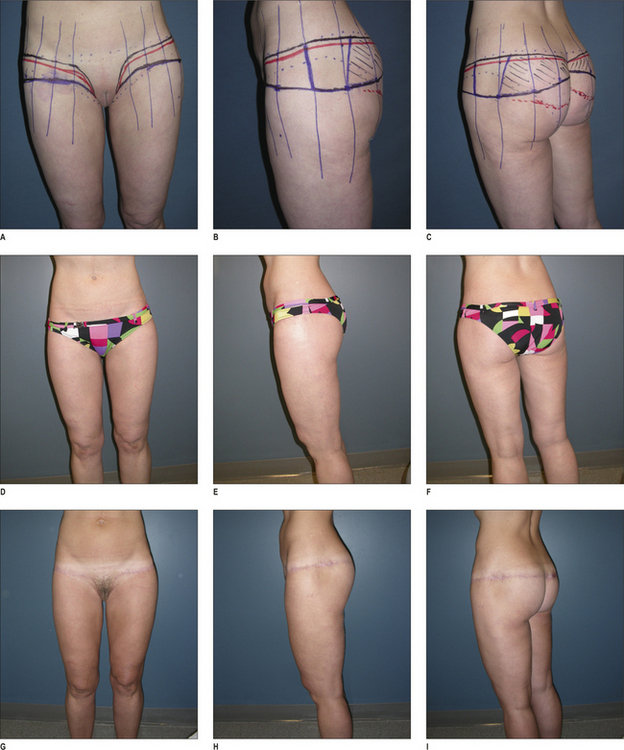

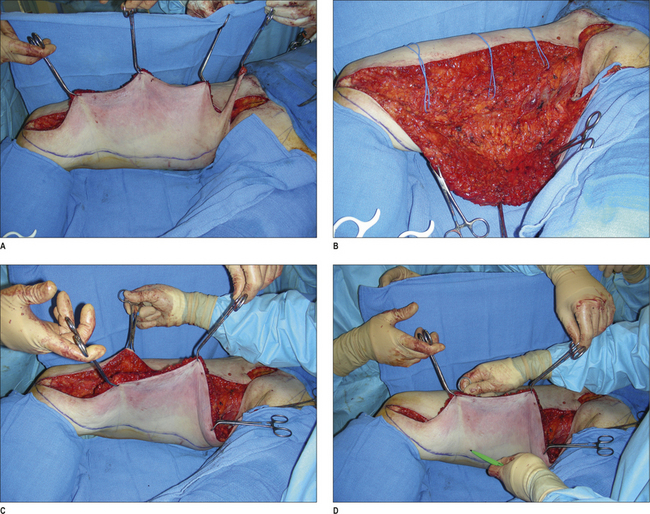

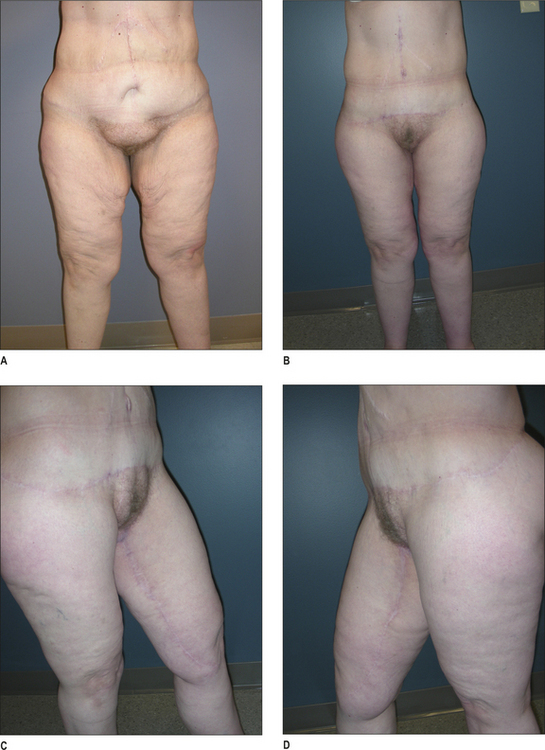

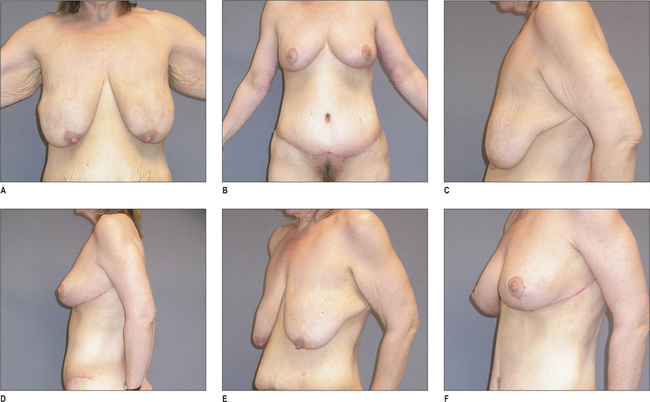

In designing the operation, one must abandon the notion that the markings will be based upon specific anatomic landmarks. Rather, the following concept should be applied to each specific body type: a higher (more superior) circumferential resection will directly excise flank rolls and emphasize the waistline, while a lower (more inferior) resection will effect a stronger elevation of the lateral thigh tissues and provide a greater ability to contour the buttock region using autologous tissue flaps. It is the authors’ preference to keep the resection as low as possible to maximize the correction of saddlebag deformities and optimize buttock shape. Abdominal-wall plication and vertical abdominal skin resection, when indicated, provide adequate waist definition. The markings begin with the patient in the supine position. With upward stretch on the lower abdominal tissues, a mark is made in the midline 6 cm superior to the anterior vulvar commissure. This point should rise just above the pubic symphysis on stretch, but may not in some patients with a long torso. In such cases, this mark should be moved superiorly by 1 or 2 cm until it as above the symphysis. The markings continue with the patient in the standing position facing away from the surgeon. The first critical decision is to select the superior anchor line. The superior anchor line will be the superior line of incision. Once again, efforts should be made to keep this line as low as possible in order to maximize the tension on the lateral thighs and the ability to reshape the buttock. Once the superior anchor line is drawn in, this will extend from approximately the mid axillary line to the posterior midline bilaterally. Vertical reference marks are drawn in at six centimeter intervals. This will help guide symmetry in the markings as well as help with re-approximating the tissues. Next, a pinch test is used to draw the inferior tissues up to the anchor line and estimate the amount of the resection. This involves rolling the inferior tissues under the anchor line to most accurately estimate the amount of tissue to be removed. As the lateral tissues are estimated, the patient is asked to slightly abduct the legs. Each estimated point of resection is made along the vertical hash marks. The inferior line of resection is then drawn. The lateral margin of resection is then selected. This connects the superior and inferior lines of incision. This is usually at the region of the mid-axillary line, and will be a transition zone between the posterior and anterior resections. At this point, estimation is made about the amount of adipose tissue that will be preserved to shape the buttock region. The overlying concept is that this operation is not entirely a resection of tissue, but rather a repositioning of tissue in the buttock region. To reach this goal, an area of adipose tissue is marked that will be preserved. This can take the form of either an island of adipose tissue, or an actual fasciocutaneous flap that will be undermined in its lateral region and transposed into the inferior buttock region. The vertical reference lines are used to help insure symmetry of these markings for this adipose tissue paddle. The patient is then asked to turn and face the surgeon. With upward tension exerted on the tissues on the patient’s right hip, a line is drawn from the lower margin of resection and connected to the point above the mons. The same maneuver is then repeated on the contralateral side. The line just drawn will represent the line of incision for the abdominoplasty part of the operation (Fig. 21.8). Once under anesthesia, the patient is positioned prone to start. The foley catheter is inserted to monitor urine output. Warming blankets and appropriate padding are placed on the operative table. The legs are prepped in a circumferential fashion. The calf compression boots are placed on each leg prior to induction of anesthesia. The electric cautery grounding pad may be placed on the calf beneath the compression boot. The authors generally use two electric cauteries at one time so that the operation can be performed in a team fashion. Two arm boards are placed at the lower end of the table so the legs can be abducted. These arm boards are well padded. Standard betadine prep is used. Epinephrine (1 : 100 000) is mixed in the operating room (1 cc epinephrine 1 : 1000 per 100 cc normal saline). This solution is injected into the dermis before incising skin in order to control bleeding from the dermal edges. The region of gluteal fat that was marked to be preserved is then stripped of epidermis using a sharp scalpel blade. A powered dermatome can also be used for this step. Next, the adipose paddle that had been stripped of epidermis is circumscribed and dissected down to the level of the fascia. This is followed by removal of the skin and subcutaneous tissue surrounding the paddle within the borders of the posterior resection. The lateral margin of resection is also incised. The adipose tissue fat is then undermined in its lateral region at the level of the muscle fascia. This allows mobilization of the tissue flap inferiorly. A subcutaneous pocket is then undermined in the buttock region inferior to the region of resection. The tissue flaps can be mobilized into the subcutaneous pocket and secured in this location with permanent braded nylon sutures placed into the muscle fascia. Because the dermis had been preserved on the tissue flap, this dermal surface area can be plicated using either permanent or absorbable sutures to enhance projection in the buttock region (Fig. 21.9). The Lockwood discontinuous undermining device (Byron Medical, USA) is passed in the subcutaneous tissue of the lateral thigh on both right and left sides. This allows mobilization of the thigh tissues during closure. To facilitate the tension-free closure in the lateral aspects of the posterior wound, the legs are abducted onto the extended arm boards that had been placed in the lower region of the bed. As an alternative, a well-padded sterile side table can be used (Fig. 21.10). The wound is secured with towel clips to approximate the skin edges. Interrupted braded sutures are placed in the subcutaneous tissues (superficial fascial system). There is still controversy as to whether these sutures should be permanent or absorbable. There is no clear scientific evidence on which to firmly base this decision. The dermis is closed in two layers, with interrupted deep dermal sutures followed by a running absorbable monofilament suture. The large lateral dog ears are simply stapled shut. When the patient is turned supine, these dog ears will be resected. Closed suction Jackson-Pratt drains are placed in the posterior wounds, and taken out through the operative incision. Cyanoacrylate adhesive is placed over the wound. This is followed by layered gauze dressings and an occlusive plastic dressing so that the wound is protected during the remainder of the procedure. The patient is then turned to the supine position. The room is warmed during the flip, and care is taken to keep all intravenous lines, catheters, and drain tubes, free of entanglement. The patient is prepped once again after the flip. The line connecting the lower aspect of the lateral margin of resection with the low transverse abdominoplasty incision is incised. At this point, the procedure is essentially the same as any abdominoplasty. The degree of undermining and plication of the abdominal wall muscles will be dependent on the patient’s body type and surgeon preference. A fleurde-lis resection may be safely combined with a body lift. Once the abdominoplasty flap is ready to be resected, the operating table is flexed to facilitate this process. If the posterior resection is set low/inferior, flexing the waist in the supine position will not put much tension on the posterior closure. If, however, the posterior resection is high/superior on the trunk, flexing the waist may apply pull on the posterior closure and a less aggressive resection should be planned. During the flap resection, the lateral dog ears at the transition point between anterior and posterior resections will be completely excised. Two closed suction drains are placed in the abdomen. The abdominal closure involves deep dermal interrupted sutures followed by a running monofilament absorbable suture. SFS sutures, using absorbable braided suture are placed in the lateral high-tension areas. For postoperative care, the patient is kept in a ‘beach chair’ position, flexed at the waist. The patient is instructed to be out of bed with assistance by the following morning or the same night, if possible. The average inpatient stay is 2 nights for this procedure. An example of a body lift without fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty is shown in Figure 21.11. An important adjunct to the lower body lift, especially in staged cases, is debulking liposuction of the thighs. Figure 21.12 shows a patient, with significant adipose tissue on her thighs, who underwent bilateral circumferential thigh liposuction concurrent with her abdominoplasty. This deflates the thigh tissues and facilitates a good aesthetic contour during a second-stage vertical thighplasty. Some patients with previous abdominoplasty may present for a lower body lift. In such cases, the conduct of the operation is the same as described above, except that the anterior incisions are merged into the previous abdominoplasty scars. This may involve a secondary ‘tightening’ of the previous abdominoplasty. In patients with or without a previous abdominoplasty, a Lockwood Type I lower body lift can be employed (Fig. 21.13), with the anterior scars veering into the groin crease bilaterally. This will provide a moderate degree of pull on the medial thigh tissues. A key point is to keep the scars very close to the mons region so that they do not descend below the level of the groin crease.

Vertical thigh lift

The medial thighs present many technical challenges for the plastic surgeon.26,27 On a practical level, patients with significant skin laxity on both medial and lateral thighs can rarely be treated satisfactorily with a single procedure. The lower-body lift can provide a significant correction of lateral thigh laxity through superiorly directed traction, but will have only a minimal impact on the medial thighs. Similarly, a vertical thighplasty will impact the medial thighs and decrease leg circumference while leaving notable deformities on the lateral thighs untouched. These concepts must be thoroughly conveyed to patients, who often present with a complaint of ‘ugly thighs’ while clutching the redundant skin on the medial thigh. There are well-selected patients with reasonable tone on the lateral thigh and buttocks who can benefit from an isolated vertical thighplasty. However, a majority of MWL patients will require both lower-body lift and vertical thighplasty to achieve a complete aesthetic correction of the thighs. It is the authors’ preference to stage lower-body lift and vertical thighplasty, with the lower-body lift serving as the initial ‘cornerstone’ procedure. This is beneficial for the following reasons:

A simple crescenteric transverse medial thigh excision is an operation that should always be considered and discussed with patients when addressing medial thigh deformities. This operation, however, is very much underpowered, and can only provide enough upward pull to improve laxity in the upper third of the medial thigh. Patients may hold the misimpression that the force of pull can be transmitted all the way to the knee. Because the vector of pull is directly vertical and the thighs are constantly moving, the transverse scars are prone to descent. This can be mitigated by keeping the scars close to the mons (actually superior/medial to the groin crease) and anchoring the deep SFS tissue to Colle’s fascia.28 This procedure also tends to result in a lot of pleating along the transverse scar that takes time to resolve. This operation does have its advantages. It avoids a visible longitudinal scar and is of much less magnitude than the full vertical thighplasty. Additionally, this version of the thighplasty can be safely combined with a lower-body lift. Achieving patient satisfaction with this procedure depends upon selecting a patient with primarily proximal medial thigh deformities and properly conveying the limitations of the operation.

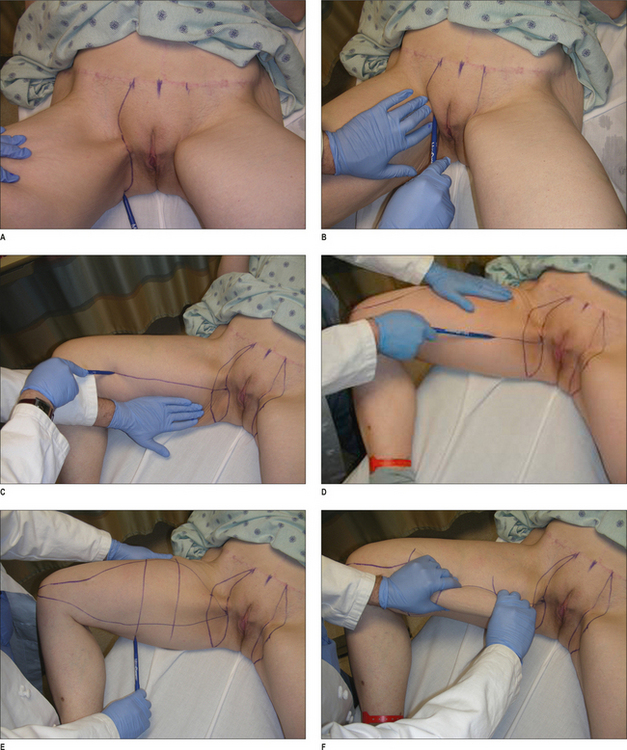

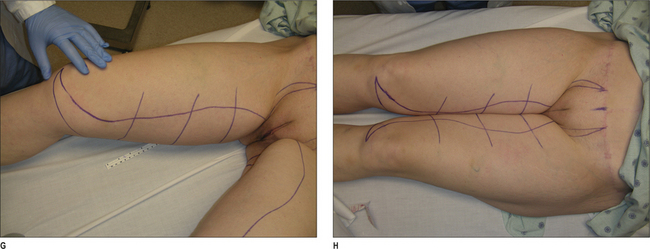

Vertical thigh lift, like brachioplasty, involves a significant visible longitudinal scar on the extremity. The scar is placed on the medial side of the upper thigh, and extends from the groin to the knee. A transverse scar component in the groin crease is usually necessary; however, this can usually be veered in one direction, either anterior or posterior, to avoid a ‘t’ incision in certain cases. The markings begin with the patient in the supine position, with the knees bent in a frogleg position (Fig. 21.14). The midline of the mons region is marked. A distance of 4 cm lateral to this midline mark is then measured. This will represent the border of the scar along the mons region. While this may seem to be a short distance from the midline, the scar will move laterally under tension. The line of incision is drawn along the groin crease and extended into the gluteal fold. The length of this scar can be variable based on the degree of skin laxity, and will represent the transverse component of the scar for the vertical thigh lift. Next, the extent of the vertical skin resection is estimated and marked with a pinch test applied to move the thigh skin upward to meet the line of incision just drawn in the groin crease. Next, the anterior anchor line is drawn in on each leg. With posterior traction on the skin of the thigh with the surgeon’s left hand, a straight line is drawn from the level of the knee up to the groin crease. At the knee, the distal margin of the incision should curve gently under the patella. The scar will cross the knee in the mid-axial position and not interfere with ambulation. Proximally, the line of incision should meet the groin crease incision just posterior to the adductor muscle origin. The traction is released from the tissues and applied in the opposite direction. With the surgeon’s left hand, traction is placed in an anterior direction. A similar line is drawn in exactly the same position along the thigh. Under traction, that line will represent the position of the final scar on the medial thigh. Next, transverse reference marks are drawn in to assist with tissue reapproximation. The same process is repeated on the opposite leg. As a check for symmetry, the legs are pushed together to observe the reflection of the markings on each thigh. These should essentially be mirror image markings. A cautionary note, however: there may be some asymmetry of the thighs to start with.

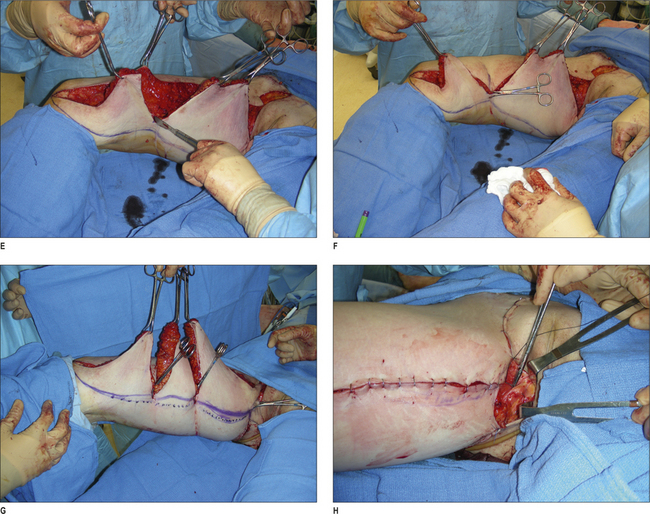

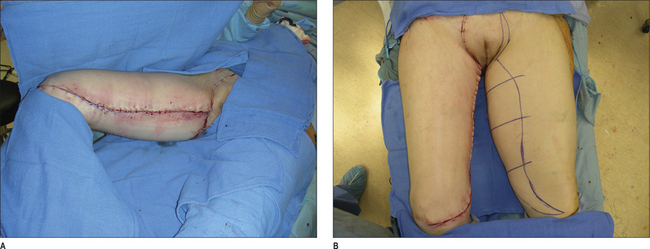

In the operating room, the patient is positioned supine and the legs prepped circumferentially. Calf compression boots are applied for induction and sterile drapes wrapped around the calves covering the sequential compression devices. This is done in a manner that would allow the legs to be freely mobilized during the surgery. The incision lines are infiltrated with epinephrine (1 : 100 000) without lidocaine. If an operating table with spreader bars is available, such as a urologic cystoscopy table, this allows an operator to sit between the abducted legs. The dissection begins with incising the anterior anchor line and the groin crease incision (Figs 21.15 & 21.16). We do not commit to the posterior margin of resection at this time. The entire anterior anchor line is incised, as well as the anterior portion of the transverse region of resection. The dissection over the femoral triangle is kept very superficial to avoid injury to the underlying lymphatic structures. Once the adductor tendon is reached proximally on the thigh, the dissection can be taken into a deeper plain. Distally, the dissection is started in a plane that leaves some adipose tissue over the muscle fascia. The saphenous vein is identified distally and preserved during the dissection. The plane of dissection is kept right above the saphenous vein. An effort is made to preserve some adipose tissue around the saphenous vein because the lymphatics run with this structure. Tributories of the saphenous vein are controlled with surgical clips. The tissues are undermined in a posterior direction until the estimated mark of resection is reached. At this time, the actual posterior margin of resection is rechecked using a flap marker or similar technique. The authors often approach this resection in a manner similar to that of the brachioplasty. In different points along the leg, the flap is incised to the intended point of resection and secured with a towel clip. The intervening segments of tissue are then removed. Once the tissue is resected, a closed suction Jackson Pratt drain is placed from the groin incision all the way to the distal point of resection at the knee. The wound is then closed in layers, with running braded absorbable suture in the SFS layer. Interrupted deep dermal sutures are placed along with a running subcuticular suture of absorbable monofilament material. Three to five braided permanent sutures are used to secure the SFS to Colle’s fascia on both sides posterior to the adductor muscle tendon. The transverse groin incision is closed with a running nylon suture. For postoperative care, ace wraps are secured on the legs. The patient is instructed to keep legs elevated in the early postoperative period, and compressive hose are used for 2–4 weeks. Figure 21.17 demonstrates the results of a vertical thighplasty in the absence of a lower-body lift. Complications of leg swelling and temporary lymphedema may be observed in the first 2–6 weeks following surgery. Drains are removed when output is <30 cc/24 hours. There are two variants of this procedure worth noting. The transverse thigh lift without a vertical component of resection was mentioned earlier, and only involves the transverse crescent-shoped resection shown in the marking diagrams. Another variant to this procedure is a short vertical scar thigh lift. This is similar to the vertical thighplasty described above, except the scar is truncated in the mid thigh. While it is an appealing concept, it is often difficult to achieve satisfactory results. There is often a noticeable step-off in contour at the transition between the end of the scar and the lower portion of the thigh. Candidates for this operation tend to have good skin tone in the lower or distal thigh and obvious festoons in the upper thigh that cannot be corrected with a transverse thigh lift.

Brachioplasty

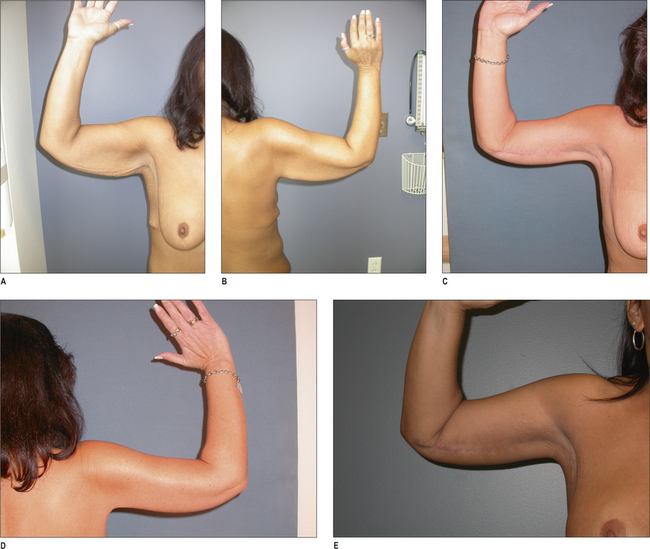

Aesthetic brachioplasty was described in the 1950s by Correa-Iturraspe and Fernandez.29 Many variations exist for correction of excess skin of the arms with regards to location of the incision either in the brachial groove or more posteriorly. In addition, the axilla may be managed with the inclusion of Z-plasties, W-plasties, or L-plasties to mitigate scar contracture.30–33 Permanent sutures securing the superficial fascial system to the axillary fascia may help to retain the axillary fold after skin excision.34 The use of a single longitudinal elliptical pattern of resection along the upper arm has been helpful in treating arm ptosis, but does not address laxity of the axillary fold. To achieve a good aesthetic result, one must extend the resection into the axillary region.

Brachioplasty best exemplifies a trade off of skin for scar. The scar from a brachioplasty is very prominent and visible. Moreover, this scar can stay thick and red for many months before maturing and becoming less noticeable. This element of preoperative counseling is vital with brachioplasty candidates. Silicone sheeting or paper tape, along with massage, can help with scar maturation. Patients should be well informed about the possibility of poor scar formation and they should be accepting of the scar location. While there is controversy over the ideal location of the scar in brachioplasty procedures, the authors prefer the bicipital groove. In this position, the scar is more difficult to see in most situations. Patients who understand the fact that they are trading redundant skin for a visible scar, and are also willing to be patient while the scar matures, are likely to be satisfied with the operation. Patients who are not well informed of this fact may be quite dissatisfied with the results and may even seek litigation.

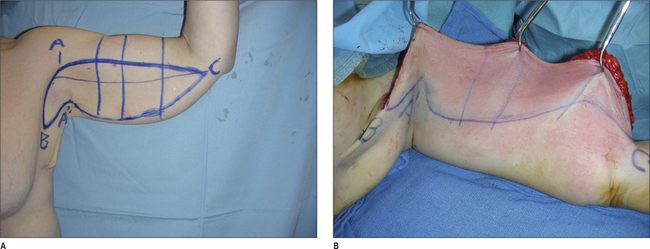

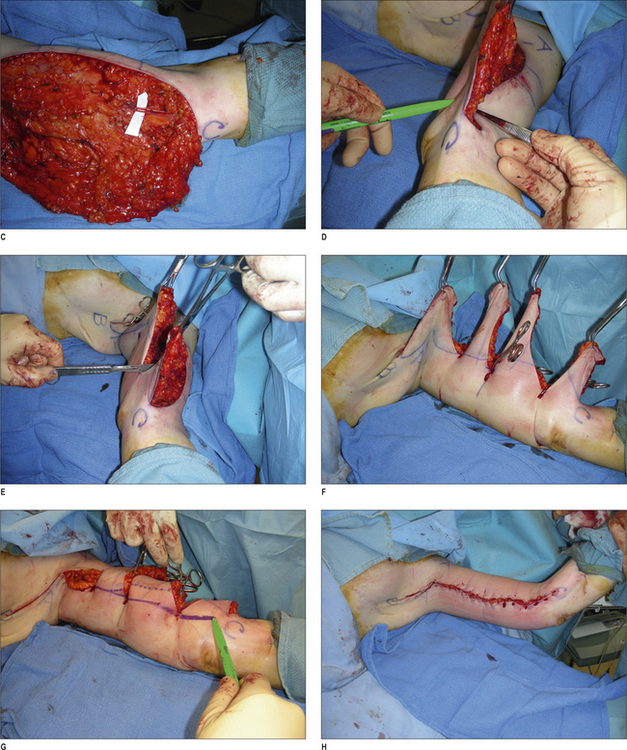

A brachioplasty may be performed as an isolated procedure, although many MWL patients choose to combine brachioplasty with other body-contouring procedures. Assessment of the brachioplasty candidate begins with a careful evaluation of excess adipose tissue on the arm as well as skin redundancy. The plastic surgeon will encounter a subset of arm-contouring patients with excess adipose tissue and relatively good skin elasticity. These patients would be good candidates for liposuction alone as a surgical option. Even if it is not completely clear that liposuction alone can be performed without loosening of the skin, patients who are reluctant to accept a scar may choose this option as an initial procedure. This would be done with the understanding that an excisional procedure could follow in the future if the patient is unhappy with skin laxity. When skin laxity is present, an assessment should be made as to the distribution and extent of the skin laxity on the arm, axillary region, and lateral chest wall. It is very important to correct the entire combined aesthetic unit of arm, axillary fold, and lateral chest wall together. As mentioned, a simple elliptical incision on the upper arm may correct circumferential skin laxity, but will not correct the axillary fold descent. The surgical goals for correction of redundant skin on the arm include: proper scar placement, elevation of the axillary fold, avoidance of uneven resection, avoidance of over resection and correction of laxity on the lateral chest wall. The authors advocate placement in the bicipital groove, and hold the opinion that a posterior scar, while less visible to the patient, is quite visible to other people. Elevation of the axillary fold is accomplished with a flap of tissue brought high into the dome of the axilla. Avoidance of uneven resection is best accomplished through a technique of on-table flap marking during the resection. This is done in a segmental fashion, which allows for accurate tailoring of the contour during the procedure. Simply marking all margins of resection on a brachioplasty and excising can result in uneven resection that is quite noticeable to the patients. Importantly, that strategy may also lead to over resection of tissue and an inability to close the wound.

Brachioplasty markings are shown in Figure 21.18. The patient can be sitting or standing with the arms bent at 90 ° at the elbow and 90 ° abduction at the shoulder. The bicipital groove is marked first, and will represent the intended scar placement location. Next, a superior line of incision is marked. This anchor line is determined by pulling tension downward on the skin of the arm to estimate skin excursion under stretch. In general, the superior line of incision is 2–3 cm superior to the bicipital groove mark. Under the tension of wound closure after resection, the superior line of incision will be pulled downward to the level of the bicipital groove. The distal extent of the resection (Fig. 21.18A – point c) is usually at the level of the elbow. By placing the resection along the bicipital groove, any scar will cross the elbow in the midaxillary position relative to the joint. This allows one to extend the incision distally without fear of joint contracture. With that in mind, however, we do this only when necessary and tend to limit extension of the scar onto the forearm because it can be very visible. The proximal extent of the superior incision line (Fig. 21.18A – point a) is set high into the dome of the axilla. Extending inferiorly from point a and at a 90 ° angle from the superior line of incision, is the extension of the incision onto the chest wall. The length of that incision (terminating at Fig. 21.18A – point b) is determined by the relative skin laxity on the lateral chest wall. As the skin laxity increases, a greater extension is necessary. Next, a point in the axilla is selected that will reach ‘point A’ under tension and will correct the descent of the axillary fold. This mark, referred to as ‘point A prime’, is usually 4–5 cm from ‘point A’. A simple pinch test is used to estimate point a prime. Next, the estimated inferior line of incision is determined by a simple pinch test. This line is only an estimate and will not be incised at the start of the procedure.

In the operating room, the arm is prepped distally to the elbow with a sterile towel wrapped around the arm. Intravenous catheters may be placed distal to the elbow. A blood-pressure cuff may be placed on the forearm as necessary. The arm is prepped circumferentially and the shoulder included in the sterile field. If liposuction is to be performed, a small amount of fluid is infused into the posterior arm (1 cc tumescent fluid per each 1 cc of anticipated aspirate) and the fat tissue is removed immediately through a port site at the elbow. The superior line of incision and the line marking the extension onto the chest wall are incised (Fig. 21.18). The soft tissue is dissected to a level just above the brachial fascia. A flap consisting of skin and subcutaneous tissue is then elevated away from the fascia and dissected inferiorly. Care is taken to identify and preserve sensory nerves running through the field of dissection. The most notable of these is the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (MABC). This is readily identified in association with the basilic vein at the distal upper arm. After dissecting distally to the estimated inferior line of incision, the actual margin of resection will be determined. An assistant grasps the forearm and elevates the arm above the operating table so that the tissues of the posterior arm are not tethered. A heavy forceps is used to transpose the superior margin of resection beneath the dissected flap and estimate how much tissue can be removed (flap marking technique). This is done at three points along the upper arm. The flap is then divided with a scalpel at these measured intervals and secured to the superior line of incision with a sharp towel clip. This method of segmental marking and incising will help establish an even contour of the arm. The tissue in the axilla is then excised with a scalpel. A new line of inferior incision is marked in between the towel clips and the remainder of the tissue is excised. Next, the superficial fascia at point A′ is secured to a clavipectoral fascia at point a with a permanent 0-braded nylon suture. This will help keep the tissue suspended in the axilla. A closed suction drain is placed in the wound extending out to the elbow and towel clips used to secure the tissues and immediately replaced with staples. It is important to align the skin edges as soon as possible after resection so that edema does not increase and prevent closure of the wound. The dermis is then closed in layers with absorbable suture. Following wound closure, a sterile compressive wrap is placed on the arm. The arm is unwrapped on the 3rd to 5th postoperative day and the wounds checked. The patient is advised to avoid heavy lifting for at least 2 weeks. In addition, the patient is advised not to raise their arms and abduct the shoulders above 90 ° for the first week. Drains are discontinued when output ≤30 cc/24 hours. After 2 weeks, the patient is prescribed gentle active range-of-motion exercises to fully abduct the shoulder. Figure 21.19 shows a representative case with maturation of scar over time.

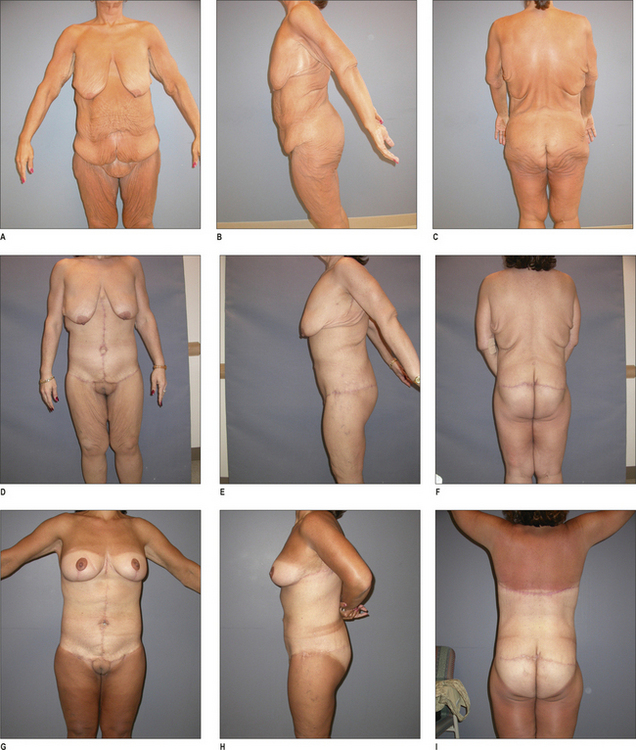

Specialized mastopexy technique in the MWL patient, including upper-body lift

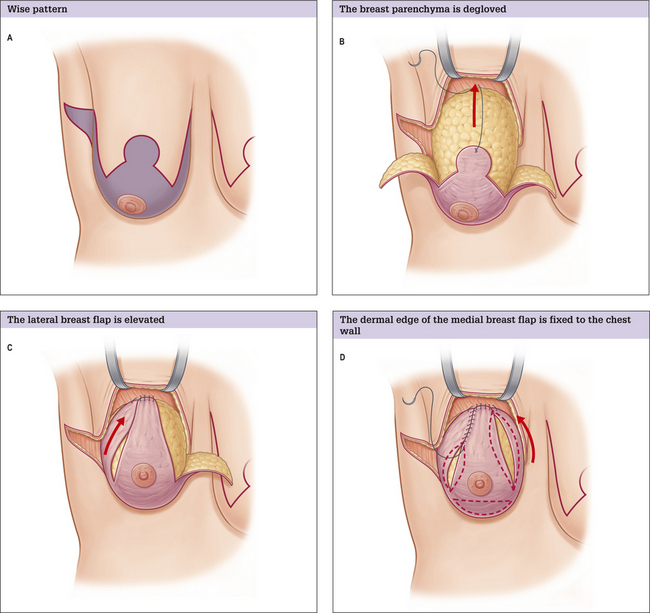

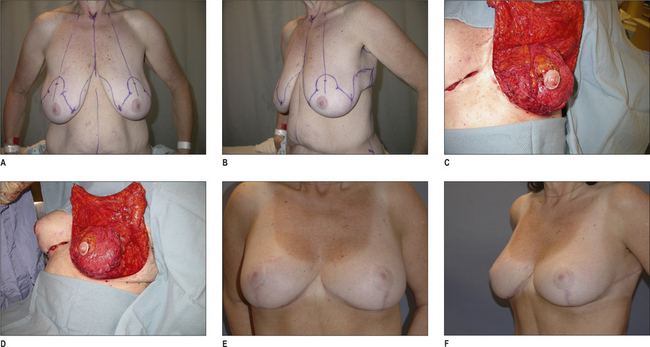

Breast deformities after massive weight loss are characterized by deflation and distortion. In particular, there is significant volume loss, elasticity loss, asymmetry, medialization of the nipples, and continuation of laxity to the lateral chest wall and to rolls in the back. Traditional techniques of breast reduction and mastopexy, especially with short scars, tend to be insufficient solutions for this deformity. The senior author has developed a technique using principles of dermal suspension and total parenchymal reshaping to fundamentally create an internal brassiere and provide lasting shape to the breast.34 A modification of the traditional Wise pattern provides control of the skin envelope and a central dermoglandular pedicle is well-vascularized and supports the nipple. Volume is maintained and autoaugmentation using excess tissue from the side of the chest lateral to the breast extending to the mid-axillary line can increase volume substantially and reliably. Approaches to the breast should take into consideration excess skin of the lateral chest wall as well as the back. If rolls are prominent in a horizontal fashion on the back, their excision can be incorporated into the mastopexy or brachioplasty for a complete upperbody lift. Rolls that have a more vertical orientation can be excised vertically along the mid-axillary line and may be in continuity with brachioplasty scars. Improving the arms, breasts, and back can help create a more harmonious appearance to the upper-body aesthetic unit.

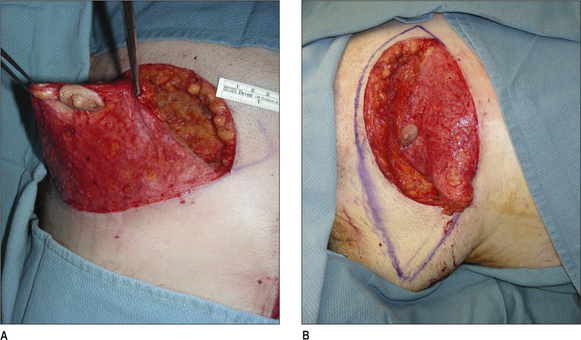

In marking the patient, the nipple position is referenced to the inferior mammary fold, and moved to a more lateral position along a symmetrically drawn breast meridian. The lateral portion of the Wise pattern is extended posteriorly to encompass the axillary skin roll and provide additional autologous tissue for breast volume. The Wise pattern can be extended to the posterior axillary line and beyond, depending on the extent of the lateral skin roll and the amount of tissue desired for autologous breast augmentation (Figs 21.20 & 21.21). The robust blood supply of the lateral thoracic region allows for a significant amount of tissue to be safely mobilized to the breast. We must make an important point: the area of skin resection to alleviate the lateral skin roll may extend beyond the portion of the Wise pattern to be de-epithelialized (i.e. a portion of the lateral ‘wing’ of the Wise pattern may be de-epithelialized and saved to assist in the reshaping and add volume, while the remainder is simply excised to eliminate the skin roll). This flexibility in design allows the surgeon to control the skin envelope and titrate the amount of lateral tissue to mobilize to the breast.

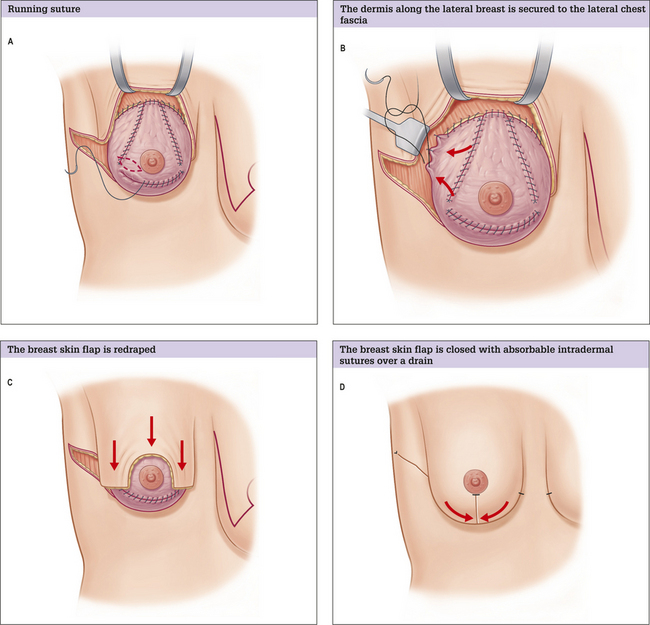

The entire region within the Wise pattern is deepithelialized. The breast parenchyma is then completely degloved by raising a 1.5 cm thick flap overlying the breast capsule. Once the chest wall is reached, undermining continues over the pectoralis major fascia to the level of the clavicle. Medial and lateral flaps of breast tissue are mobilized by undermining over the chest wall. Care is taken to preserve significant perforating vessels that enter the tissue flaps near the base. The lateral flap is trimmed to the desired size, as necessary. The nipple survives on a healthy central pedicle.

The next step is the suspension of the central dermal extension to the chest wall. This is performed with a 0-braided permanent suture in a mattress fashion. The dermis is firmly tacked to the periosteum of a selected rib along the breast meridian. This carefully placed suture must pass through the pectoralis muscle and relies on palpation of the rib with the non-dominant hand to guide the needle pass. The choice of rib level for fixation is made intraoperatively based on the distance between the dermal edge and the nipple (i.e. how nipple areolar complex position is affected by height of suspension). This is most often the second rib. The suspension should raise the level of the nipple close to the intended final position. The lateral breast flap is then suspended and secured to the chest wall by tacking to the rib periosteum in a similar manner. The lateral flap dermal suspension suture will be very close to the central suspension suture, although a lower rib level may be selected to provide the desired shape. This will create a discrete lateral curvature to the breast shape and replace the unsightly blending of breast tissue with the lateral chest. The medial breast flap is then suspended and secured to the chest wall. With the suspension points established, control of the parenchymal shape is then gained. The broad surface area of dermis is meticulously plicated with running absorbable sutures to adjust the shape. The process starts with approximation of the dermis of the lateral flap to the central dermal extension. This is followed by plication of the medial flap dermis to the central dermal extension. The inferior pole of the breast is then plicated to shorten the nipple to IMF distance and increase projection. The authors have learned to carry out the suspension and plication steps simultaneously on both breasts, rather than completing one breast and moving to another. This permits better symmetry. After initial placement of plication sutures, a fine-tuning process follows in which additional plication sutures are added. Sutures may be necessary to secure the lateral breast flap to the lateral chest wall fascia. Constant redraping of the skin flap during the shaping process helps guide both major and minor adjustments to breast form. If the abdominal-wall tissues are very loose, a decision may be made to secure the superficial fascial system (SFS) layer of the dissected edge of the abdominal wall to the periosteum of the 5th rib. This will restore IMF position.

Restoration of breast shape and symmetry can be achieved in difficult cases with this technique. Patient satisfaction has been high in all cases. Pre and postoperative results are shown in Figures 21.22 and 21.23. The upper-body lift pattern of resection and results are shown in Figure 21.24.

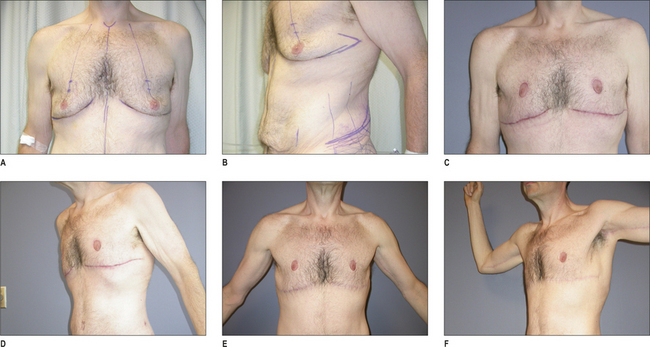

Specialized gynecomastia correction technique in the MWL patient

The severe skin deformities of the male chest following massive weight loss are difficult to correct without a major skin excision. Moreover, periareolar techniques do not work well in this population. The authors advocate an elliptical excision of chest skin with preservation of the nipple on a thinned broad-based dermal pedicle. The scar position is in the inframmary fold. Figures 21.25 and 21.26 show the results of technique and the dissection of the pedicle.

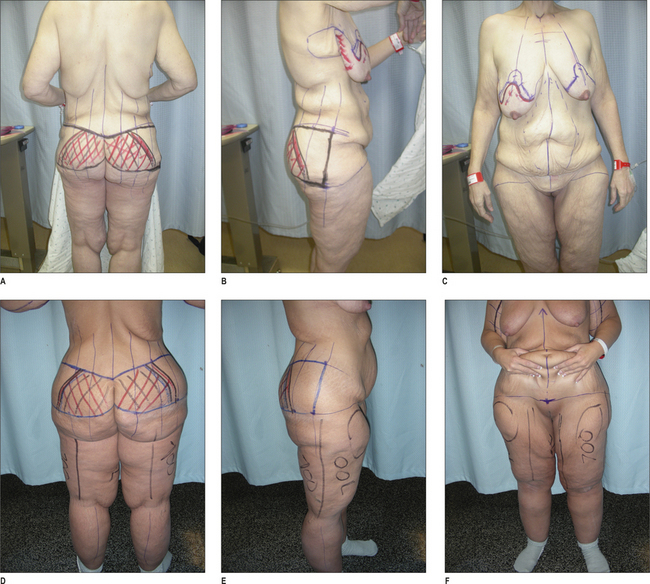

Multiple procedures and staging

Multiple procedures may be combined, providing safety is the overriding principle and the operative-setting appropriate (e.g. inpatient facility). When combining procedures, the authors avoid combinations that will result in opposing vectors of pull. An example would be combining lower-body lift and upper-body lift. Additionally, both the magnitude of recovery, given the patient’s age and medical condition, should be considered. The experience of the operative team, number of operating surgeons, and potential for surgeon fatigue should also be taken into account. In general, the authors will do as much as a circumferential lower-body lift and one upper-body procedure in a single operative setting for well-selected patients. When planning staged procedures, the authors allow at least 3 months between stages. Well-planned stages can result in a safe total body contouring (Fig. 21.27).

1. Livingston E.H. Preface: bariatric surgery. Surg Clin N Am. 2005;85:xiii-xvii.

2. Santry H.P., Gillen D.L., Lauderdale D.S. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1909-1917.

3. Davis M.M., Slish K., Chao C., et al. National trends in bariatric surgery, 1996–2002. Arch Surg. 2006;141:71-74.

4. Nguyen N.T., Goldman C., Rosenquist C.J., et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2001;234:279-289.

5. Pope G.D., Birkmeyer J.D., Finlayson S.R. National trends in utilization and in-hospital outcomes of bariatric surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:855-861.

6. Buckwald H., Avidor Y., Braunwald E., et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-1737.

7. Safadi B.Y. Trends in insurance coverage for bariatric surgery and the impact of evidence-based reviews. Surg Clin N Am. 2005;85:665-680.

8. American Society of Plastic Surgeons Statistics. 2006. wwww.plasticsurgery.org.

9. Song A.Y., Jean R.D., Hurwitz D.J., et al. A classification of weight loss deformities: the Pittsburgh Rating Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1534-1554.

10. Matory W.E., O’Sullivan J., Fudem G., et al. Abdominal surgery in patients with severe morbid obesity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:976-987.

11. Vastine V.L., Morgan R.F., Williams G.S. Wound complications of abdominoplasty in obese patients. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:33-35.

12. Shermak M.A. Hernia repair and abdominoplasty in gastric bypass patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1145-1150.

13. Kelly H.A. Excision of the fat of the abdominal wall lipectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;10:299.

14. Lockwood T. High-lateral-tension abdominoplasty with superficial fascial suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:603-615.

15. Matarasso A. Abdominoplasty. A system of classification and treatment for combined abdominoplasty and suction-assisted lipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1991;15:111-121.

16. Dellon A.L. Fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1985;9:27-32.

17. Persichetti P., Simone P., Scuderi N. Anchor-line abdominoplasty: A comprehensive approach to abdominal wall reconstruction and body contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:289-294.

18. Mühlbauer W. Radical abdominoplasty, including body shaping: representative cases. Aesth Plast Surg. 1989;13:105-110.

19. Aly A.S., Cram A.E., Chao M., et al. Belt lipectomy for cicumferential truncal excess: The University of Iowa experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:398-413.

20. Lockwood T.E. Lower-body lift. Aesthetic Surg J. 2001;21:355.

21. Van Geertruyden J.P., Vandeweyer E., de Fontaine S., et al. Circumferential torsoplasty. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:623-628.

22. Hurwitz D.J., Rubin J.P., Risen M., et al. Correcting the saddlebag deformity in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;8:87-95.

23. Lockwood T.E. Lower body lift with superficial fascial suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1112-1122.

24. Sozer S.O., Agullo F.J., Wolf C. Autoprosthesis buttock augmentation during lower body lift. Aesth Plast Surg. 2005;29(3):133-137.

25. Centeno R.F. Autologous gluteal augmentation with circumferential body lift in the massive weight loss and aesthetic patient. 2006;33(3):479-496.

26. Lewis J.R. The thigh lift. J Int Coll Surg. 1957;27(3):330-334.

27. Shultz R.C., Feinberg L.A. Medial thigh lift. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;2:404-410.

28. Lockwood T. Fascial anchoring technique in medial thigh lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:299-304.

29. Correa-Inturraspe M., Fernandez J.C. Dermolipectomia braquial. Prensa Med Argent. 1954;34:24.

30. Aly A. Brachioplasty in the patient with massive weight loss. Aesthetic Surg J. 2006;26:76-84.

31. Hurwitz D.J., Holland S.W. The L brachioplasty: an innovative approach to correct excess tissue of the upper arm, axilla, and lateral chest. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):403-411.

32. Strauch B., Linetskaya D., Baum T., et al. Brachioplasty and axillary restoration. Aesthetic Surg J. 2004;24:486-488.

33. Lockwood T. Brachioplasty with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(4):912-920.

34. Rubin J.P. Mastopexy after massive weight loss: dermal suspension and total parenchymal reshaping. Aesthetic Surg J. 2006;26:214-222.