9 Body image, sexuality, weight loss and hypnotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Problems associated with people’s sense of their own body have increased over recent years and discussions about body image are much more commonly found in the media, alongside those within health and social care. Orbach (2009: 1) suggests that ‘millions struggle on a daily basis against troubled and shaming feelings about the way their bodies appear’. Societal obsession with the perfect body, which includes being beautiful, fit, and slim and remaining youthful; all exert unrealistic pressures on individuals. The images of perfection are everywhere and our bodies are being shaped by forces beyond our control (Orbach 2009). It is not hard to see therefore why society is beginning to acknowledge this as a growing problem.

Over recent years, an increasing amount of literature has emerged, with a number of authors attempting to define body image and develop models relating to practice. Grogan (1999) defined body image as a person’s perceptions, thoughts and feelings about his or her body, which incorporates appearance, body size, shape and attractiveness. Concern about our bodies is normal and allows us to have healthy body awareness. However, excessive bodily concern can lead on to an abnormal focus and can result in bodily obsession or body dysmorphic disorder (Webster’s Dictionary 2008).

Disfigurement is a particularly difficult body image problem relating to more than just the visual effect of the disfigurement, but linking with the patient’s thoughts and feelings about how it was acquired. Barraclough (1999) reminds us that people cope differently with disfigurement and suggests that some people can be very self-conscious to changes that are not immediately obvious to others. It is important therefore, to assess the patient’s perception of the problem, while suspending our own judgement. One way of doing this is to adopt an approach developed by Berne’s (1972) and ‘think Martian’. When asking the person to describe how they see the problem, we suspend our personal knowledge base and judgement, in an effort to see it through their eyes. This technique is very powerful because, in addition to being empathetic, the therapist also enters into the patient’s ‘frame of reference’ by listening to the language and metaphors they use to describe themselves.

Body image is closely aligned with a person’s sexuality and as such, the authors recommend a broader working definition in order that all aspects of the patient’s persona are acknowledged. White (2006) takes a holistic view in relation to this area of practice suggesting that:

Freud (1936) also recommended a similarly broad approach, reminding therapists that sex is something we do but sexuality is something we are and as such incorporates many facets of the individual. It is important therefore, that when assessing patients, prior to offering hypnotherapy techniques, we need to ascertain how their body image concerns relate to the broader view they have of themselves, and whether this affects their roles and relationships with others.

ASSESSMENT MODELS

DIRECT/NEGOTIATION MODEL

The DIRECT/Negotiation Model (Box 9.1) utilizes a staged approach to assessing body image and sexual concerns which allows the therapist and patient to proceed at a mutually agreed level. It is a 6-stage approach which is particularly useful when negotiating with the patient as to whether they wish to discuss and work with particularly sensitive areas. Negotiation is used to elicit what the patient is comfortable working with and is used throughout the assessment, enabling the therapist to proceed at the patient’s pace. This can relate to either the depth of communication they are comfortable with, or when negotiating which hypnotherapy approaches they are happy to engage in. (For further explanation of this model, see Chapter 5, and a full version, which also includes Annon’s (1976) P.LI.SS.IT (1976) Assessment Model, can be found at: www://learnzone.macmillan.org.uk.)

BODY IMAGE MODEL (PRICE)

Price (1990) developed a 3-stage model which enables the therapist or healthcare professional (HCP) to identify and explore different aspects of a patient’s body image:

BODY IMAGE MODEL (CASH & PRUZINSKY)

Cash & Pruzinsky (2002) have developed a useful framework for assessing body image concerns. Their book offers a variety of tools which patients can use individually or can be used to form part of their therapy. A body image diary is used as a way of reflecting on their body image concerns. Patients are encouraged to notice:

Applying hypnotherapy

The American Society for Clinical Hypnosis (2009) suggests three main ways of practicing hypnotherapy:

IMAGERY

Imagery is an important aspect of working with body image issues. Two modes of imagery, which are useful in facilitating this process, are: ‘diagnostic’ and ‘therapeutic’ (Cunningham 2000).

Therapeutic imagery

Therapeutic imagery entails working in a positive way with the images the patient presents, based on the principle that images affect body function. The therapist encourages the patient to imagine beneficial changes in the images they see. The patient gets in touch with both their conscious and unconscious, to consult with their ‘Inner Healer’ in the imagination, to bring about healing from within (Cunningham 2000). From practical experience, patients work well using this approach. They are usually very inventive and can fill up empty spaces with ‘magic healing fluid’, making it the colour and consistency which is just right for them. They can change parts of the body which look dark and diseased by flushing out all the dark colours and replacing them with bright healing colours. Often the healing comes about in the patient’s unconscious through seeing themselves whole again; even though the physical reality may be different.

CLEAN LANGUAGE MODEL

Finally, another useful framework worth consideration is that developed by Grove and Panzer (1991) to resolve traumatic memories. The basis of the model is the use of what they refer to as clean language (using the patient’s words). They assert that this ensures that the patient’s meaning and resonance remains wholly intact, and is uncontaminated by the therapist’s words. Working in this way opens the door to change through developing a much more naturalistic trance which avoids evoking resistance. The therapy begins by inviting the patient to tell their narrative, paying attention to the language they use. This is done by examining the auditory, visual and kinaesthetic channels used, in addition to noting how they use language in order to describe their experiences and inner realities.

Memories

Patients generally recall events from the past. However, Grove and Panzer suggest that memories can also be anticipatory and relate to future events. The memories disclosed can either be real or imagined. They suggest that when working in this dimension the focus should be on the memory, as the words patients use simply give information. It is the memory itself which is the most significant aspect in relation to the therapy which follows (see Case study 1, Box 9.2).

Semantics

Grove and Panzer (1991) link this way of working with neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) and Ericksonian therapy, in that the therapist matches and paces the patient’s language and mirrors their body language. They assert that their model goes further as the adoption of clean language and the structuring of questions, facilitates the patient to naturally go into trance. They describe this as conversational trance, and feel that the benefits arise because patients can go inside to get the information they need, and then give feedback to the therapist in relation to what they see and how they want to work. It also allows the patient to give feedback when they have completed their task.

HYPNOTHERAPY FOR WEIGHT CONTROL

Many people gain weight due to a series of bad habits they develop over the years. This may include reaching for biscuits with a cup of tea, driving short distances instead of walking or eating heavy meals late at night. Clients will find it easier to change habits when they become consciously aware that they are not a part of themselves, but simply bits of behaviour that they have learnt and can be unlearnt. Hypnotherapeutic suggestions can help clients break old habits on an unconscious level. Suggestions can be made during the hypnotherapy session to incorporate new patterns of behaviour with regard to times, places and reasons for eating. Post-hypnotic suggestions can be incorporated into the hypnotherapy session for: symptom substitution, trading one eating habit for another healthier option; symptom amelioration, to directly reduce overeating and symptom utilization, to encourage the client to accept and re-define eating habits (Alman 1992).

BODY IMAGE AND SEXUAL ISSUES RELATING TO ILLNESS OR DISABILITY

Changes arising due to illness or disability can leave patients and their partners requiring support to adjust to the body image and sexual issues which may arise. Any support offered should aim to facilitate adjustment to the resulting changes and the losses which these may bring. Each patient’s response to his or her illness is unique, and helping them through the anxiety of adjustment requires an individualized holistic approach. People use different coping mechanisms in an effort to adjust and an initial reaction of denial has an important role in protecting against unbearable anxiety (Wells 2000). Before using any hypnotherapy techniques, the therapist needs to assess if this is the case and decide whether hypnotherapy at this time would have a positive effect. In many cases, denial operates as a healthy mechanism and protects the person against the immediate shock of reality (Cawthorn 2006). Davidhizar and Giger (1998: 44) remind us that ‘normally denial diminishes and the person begins to face and accept the harsh reality of what has been blocked’. However, when denial appears to be causing a problem or is longstanding, often the solution lies in identifying and working through what is causing the blockage. The patient’s own critical sensor will protect them if they are not ready to make any changes during trance work.

CANCER DIAGNOSIS

Being diagnosed with cancer can have a major impact on body image and can include a total body effect, as patients come to terms with their own mortality (see Ch. 14). The psychological impact of an altered appearance relating to cancer can be far-reaching and varied (Harcourt & Ramsey 2006). This is because problems occur not only in relation to the disease, but also as a result of the side-effects of treatments, which include surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy and hormone therapy. For these reasons, people may be attempting to recover from one body image change, only to be faced with one after another, which makes adjustment even more difficult.

When adjusting to body image changes, the reactions of others are very important. This is particularly relevant if the changes arise as a result of rapid disease, surgery, accidents and cancer treatments, as the person is still struggling to come to terms with their own thoughts and feelings surrounding this. John Diamond (1998) wrote extensively about the ongoing problems he experienced in relation to his oral cancer and subsequent surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. He reminds us that the negative reactions of others can inadvertently add to the problems.

Diamond (1998) writes about his responses to individual treatments. He recalls his surprise at his reaction to the loss of body hair during chemotherapy and the psychological effect this had on his manhood. He goes on to say how he was unprepared for the anger which erupted from nowhere when receiving radiotherapy and the sadness and regret that this was often directed at the ones closest to him, who were his wife and children.

Body image problems (including sexual problems) can occur in relation to any form of cancer, affecting both males and females. Many women report feeling less sexually attractive following breast surgery, as breasts are often seen as a symbol of femininity and sexual attractiveness (Burwell et al 2006). Chemotherapy can add to the problem due to hair loss and increased weight. Breast Cancer Care (2008) sums up the difficulties experienced by this client group in a quote by a patient who was undergoing chemotherapy, who when asked about her sexuality said:

Men also have body image and sexual problems relating to effects of surgery and hormone therapy for prostate cancer. Reduced fertility, and altered sexual identity or masculinity being just a few of the problems which can arise. There are many issues relating to this client group, which are covered in more detail by White et al (2006).

An example of how this approach was effective is with a young woman who learned to adjust and accommodate a tumour situated too near her spine to safely remove it (see Case study 2, Box 9.3).

BOX 9.3 Case study 2

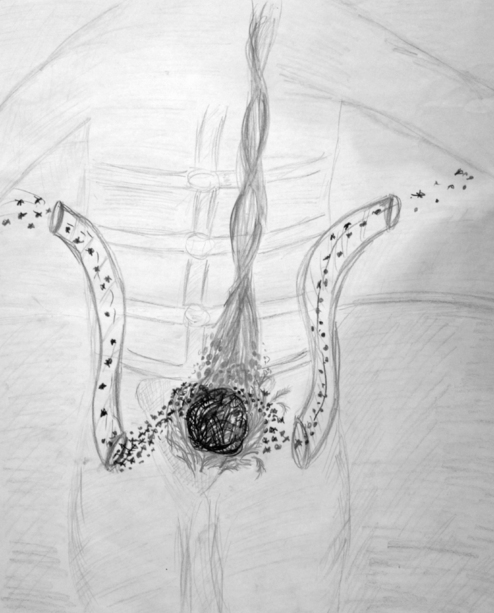

Kirsty, aged 24, came for hypnotherapy to help her to adjust psychologically and physically to a tumour within her abdomen. During imagery she saw the tumour as black and impacting on her femininity (see Fig. 9.1). She sat awkwardly and because of this complained of low back pain. In trance she was able to clear the black away and pack the area around the tumour with white feathers, making it much softer and accommodating. This resulted in her being able to sit in a more relaxed way, reducing her back pain. Hypnotherapy was used to work on an abusive relationship, and she was happy to send the abuser off in a hot air balloon. Kirsty went on to draw this work in collaboration with her art therapist. The internal changes can be seen in Figures 9.1 and 9.2 and her personal growth and healing can be seen in Figures 9.3 and 9.4. She still has the tumour in situ (currently dormant) but has adjusted to the disability it brings.

SELF-ESTEEM AND SELF-WORTH

Low self-esteem and/or self-worth can result from body image problems. However, these could be longstanding issues which the new problems further compound. Newell (1999) suggests that body image changes can affect the person’s quality of life, resulting in reduced self-confidence and low self-esteem, which in turn can cause difficult social interactions and, ultimately, social withdrawal. White (2006: 678) reminds us that ‘serious illness and disability remove a person from their accustomed personal, social and sexual relation, threatening self-esteem and attractiveness at a time when their need for intimacy and belonging may be greatest’.

When assessing patients, it is important to elicit their perception of the problem and also find out how significant others perceive it. Perceptions are important and patients often assume that their body image changes will be problematic for their partner, when in reality this is not usually the case. A Macmillan ‘super survey’ (2008) found that only 5% of partners found the patient’s body image change to be problematic (see: www.macmillan.org.uk/sex).

It is important to assess the patient’s mood, as a low mood can impact on their body image, self-esteem and self-worth. Common psychological problems include anxiety, depression and adjustment problems/disorders. People living with depression often have negative expectancy and Yapko (2001) suggests that the first task in treating a depressed client is to address any sense of hopelessness.

SECURITY

Personal security is something we do not consider when life is going well and it is only when our security is challenged by life-threatening or life-changing experiences that we become aware of it. At these times, our whole being is threatened and we begin to consider our own mortality. An example where both individual and collective security was threatened was following the 9/11 or 7/7 terrorist attacks. During this time, there was a sense of personal and collective insecurity, which took time for people to adjust and move on from. This same scenario is repeated following the diagnosis of a life-threatening or life-limiting illness and can impact on the personal security of both the patient and their family members. From an existential perspective, cancer is still (incorrectly) viewed by many to signify impending death. John Diamond (1998) wrote that when diagnosed with cancer, he saw a death sentence. For him this eventually became true, but for many, it merely raises existential concerns which need to be worked through (see Ch. 14). Illness may bring other issues which relate to security such as financial, social, role changes and the ability to maintain and develop relationships. It may also raise old insecurities which can be transformed through trance (see Case study 3, Box 9.4).

BOX 9.4 Case study 3

Sheila, a 50-year-old lady, was recovering from breast surgery and she was afraid to undress in front of her husband in case he said she was ‘ugly’. On inquiry, it transpired that her mother had called her ugly as a teenager and this is where her body image issues originated. In order to reduce the impact of this memory, an adapted NLP technique was used (Rushworth 1999). Sheila contained the image of her mother (saying she was ugly) in a television screen. Sheila had the control switch and she turned the colour down, making it black and white, then turned the sound down and finally shrunk the picture down until she was happy with it. At the following session, Sheila said that her mother (surprisingly) had made contact with her for the first time in 20 years. Sheila was able to meet her and saw that her unkind words no longer impacted on her. When Sheila realized she was projecting her mother’s behaviour on to her husband, she allowed him to see her naked without fear of rejection.

SEXUAL ABUSE/TRAUMA

When working with patients it is important to listen to how they tell the narrative relating to their concerns. The ‘clean language’ approach adopted by Grove and Panzer (1991) allows the meaning attached to the abuse/trauma to be the patient’s and not the therapist’s. If denial is evident and it is proving to be a useful coping mechanism, then this should be respected. However, if the memories are problematic, there are a number of techniques which can transform them into more positive ones where the patient regains control. Grove and Panzer (1991) suggest a variety of ways when working in this area, all of which should match up with the person’s memories, language, symbols and metaphors.

Negative images can be changed using hypnotherapy techniques. Patients can help to repair the damage by using imagery to heal the areas which they feel have been damaged. They can be supported to imagine themselves regaining control in a situation where this was not the case. If they want to change the image of a perpetrator, they can make them look silly, or shrink them down in size, or send them off in a hot air balloon. This can be achieved during trance (see Case studies 2 and 3, Boxes 9.3 and 9.4).

Where patients have unpleasant memories which they do not want to re-live, then an NLP technique adapted from Rushworth (1999) can safely wipe the memory without the patient needing to re-visit it or talk it through with the therapist. The technique currently used in practice is as follows:

Working with dreams

Another way of working with trauma is to work with the dreams or nightmares which patients recall. Mallon (2001, 2003) and Kearney and Richardson (2006) offer suggestions as to how to work with dreams, and these have been integrated into the authors’ clinical practice. They recommend avoiding over-interpretation, allowing the person to make their own sense of what the dream evokes and the symbols and feelings they contain. If the patient is comfortable recalling their dream, this can be undertaken within the therapy session or through keeping a dream diary. This involves drawing or giving a narrative of the dreams, noting the shapes, colours, whether any patterns emerge and whether the dreams are reoccurring.

Mallon (2001) suggests that a number of questions are asked in relation to the dream. These refer to who was in the dream and where was it set. If the patient was in it, were they active or passive? Was there anything which impressed them or disturbed them about the dream and what was the main feeling? Healing can sometimes come in sharing the dream. However, for many patients, if there are negative images, traumatic scenes or incomplete or difficult endings, then to transform these while in trance can be very healing. If the dream relates to an actual situation, then it is useful to inquire what the patient wants to change within the dream; whether this is images, symbols or feelings, or even having permission to say to another person what they feel is important for them to hear. If this is carefully set up, then the patient, while in trance, is usually able to achieve a positive outcome with the therapist as their companion. In practice, patients usually know how they would like the ending to be.

Alman B. Self-hypnosis. The complete guide to better health and self-change. London: Souvenir Press, 1992.

American Society for Clinical Hypnosis. Information for the general public. 2009. Online. Available: http://asch.net/genpublicinfo.htm

Barraclough J. Cancer and emotion, a practical guide to psycho-oncology, third ed. Chichester: John Wiley, 1999.

Berne E. What do you say after you say hello? New York: Bantam Books, 1972.

Breast Cancer Care. Sexuality, intimacy and breast cancer. London: BCC, 2008.

Burwell S.R., Case L.D., Kaelin C., et al. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2006;24(18):2815-2821.

Cash T.F., Pruzinsky T., editors. Body image: a handbook of theory, research and clinical practice. New York: Guildford Press, 2002.

Cawthorn A. Working with the denied body. In: Mackereth P., Carter A., editors. Massage & bodywork: adapting therapies for cancer care. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Cunningham A.J. The healing journey: overcoming the crisis of cancer. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2000.

Davidhizar R., Giger J.N. Patient’s use of denial: coping with the unacceptable. Nurs. Stand.. 1998;12(43):44-46.

Diamond J. C: because cowards get cancer too. London: Phoenix Books, 1998.

Freud S. Sexuality and the psychology of love. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1936.

Grogan S. Body image. London: Routledge, 1999.

Grove D.J., Panzer B.I. Resolving traumatic memories. Metaphors and symbols in psychotherapy. New York: Irvington, 1991.

Harcourt D., Ramsey N. Altered body image. In: Kearney N., Richardson A., editors. Nursing patients with cancer principles and practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006.

Mallon B. Venus dreaming. A guide to women’s dreams and nightmares. Dublin: Newleaf, 2001.

Mallon B. The dream bible. Hampshire: Godsfield Press, 2003.

Newell R.J. Altered body image: a fear-avoidance model of psycho-social difficulties following disfigurement. J. Adv. Nurs.. 1999;30:1230-1238.

NICE. Supportive and palliative care guidelines. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004. Online. Available: www.nice.org.uk

Orbach S. Bodies. London: Profile Books, 2009.

Price B. Body image. New Jersey: Nursing concepts and care. Prentice Hall, 1990.

Rushworth C. Making a difference in cancer care: practical techniques in palliative and curative treatment, second ed. London: Souvenir Press, 1999.

Stephenson K. Slimmer fitter healthier audio CD booklet. 2005. Innerchange Programmes

Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. third ed

Wells D., editor. Caring for sexuality in health care. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

White I. The impact of cancer and cancer therapy on sexual and reproductive health. In: Kearney N., Richardson A., editors. Nursing patients with cancer: principles and practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006.

Yapko. Treating depression with hypnosis integrating cognitive – behavioural and strategic approaches. Philadelphia: Routledge, 2001.

Changing Faces, 1–2 Junction Mews, London, W2 IPN, UK – a charity which helps people trying to cope with disfigurement. Tel: 020 7706 4232; e-mail: info@changingfaces.co.uk website:www.changing faces.co.uk

Let’s Face It, 14 Fallowfield, Yately, Hampshire GU46 6LW, UK – offers a support network for anyone affected by facial disfigurement

Menopausal Matters—Helpline 0845 122 8616; e-mail: daisy@daisynetwork.org.uk

www.learnzone.macmillan.org.uk.

www.cancerbackup.org.uk/Resourcessupport/Relationshipscommunication/Sexuality.