24 Body fluids

This atlas addresses primarily the elements of fluids that are observable through a microscope. For a more detailed explanation of body fluids, consult a hematology or urinalysis textbook that includes a discussion of body fluids, such as Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications* or Fundamentals of Urine and Body Fluid Analysis.†

When preparing cytocentrifuge slides, a consistent amount of fluid should be used to generate a consistent yield of cells. Usually two to six drops of fluid are used depending on the nucleated cell count. Five drops of fluid will generally yield enough cells to perform a 100-cell differential if the nucleated cell count is at least 3/mm3. For very high counts, a dilution with normal saline may be made. The area of the slide where the cell button will be deposited should be marked with a wax pencil in case the number of cells recovered is small and difficult to locate (Figure 24-1). Alternatively, specially marked slides can be used.

FIGURE 24–1A Wright-stained cytocentrifuge slide demonstrating a concentrated button of cells within the marked circle.

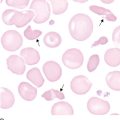

There may be some distortion of cells as a result of centrifugation or when cell counts are high. Dilutions with normal saline should be made before centrifugation to minimize distortion when nucleated cell counts are high. When the red blood cell (RBC) count is extremely high (more than 1 million), the slide should be made in the same manner as the peripheral blood smear slide (see Chapter 1). However, the examination of the smear should be performed at the end of the slide rather than the battlement pattern used for blood smears. This is because the larger, and usually more significant, cells are likely to be pushed to the end of the slide.

Any cell that is seen in the peripheral blood may be found in a body fluid in addition to cells specific to that fluid (e.g., mesothelial cells, macrophages, tumor cells). However, the cells look somewhat different than in peripheral blood, and some in vitro degeneration is normal. The presence of organisms, such as yeast and bacteria, should also be noted (see Figures 24-12 to 24-14).

Cells commonly seen in cerebrospinal fluid

Comments:

Small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes may be seen in normal CSF.

Increased numbers of neutrophils are associated with bacterial meningitis; early stages of viral, fungal, and tubercular meningitis; intracranial hemorrhage; intrathecal injections; central nervous system (CNS) infarct; malignancy; or abscess.

Increased numbers of lymphocytes and monocytes are associated with viral, fungal, tubercular and bacterial meningitis, and multiple sclerosis.

Cells sometimes found in cerebrospinal fluid

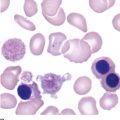

Reactive lymphocytes (Figure 24-5) are associated with viral meningitis and other antigenic stimulation. The cells will vary in size; nuclear shape may be irregular and cytoplasm may be scant to abundant with pale to intense staining characteristics. (See description of reactive lymphocytes, Figure 14-7.)

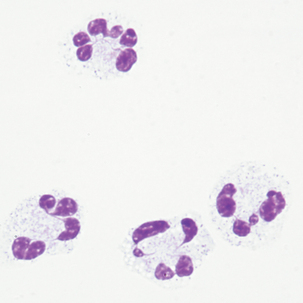

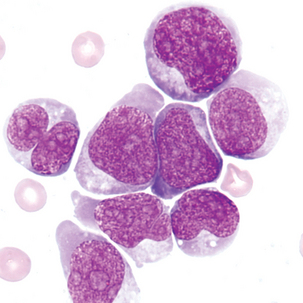

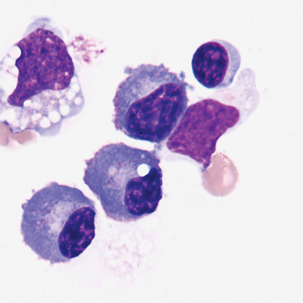

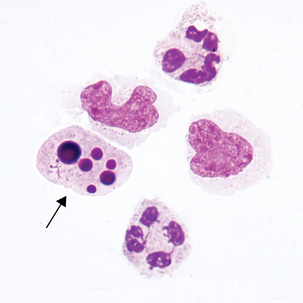

Blasts in the CSF may have some of the characteristics of the acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) blasts seen in the peripheral blood (Figure 24-6; see Chapter 16). It is not unusual for ALL to have CNS involvement, and blasts may be present in the CSF before being observed in the peripheral blood.

Cells sometimes found in cerebrospinal fluid after central nervous system hemorrhage

1.Neutrophils and macrophages—appear within 2 to 4 hours

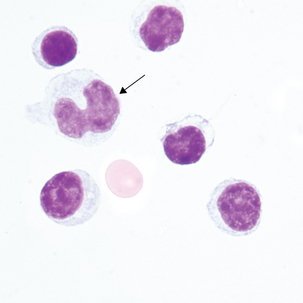

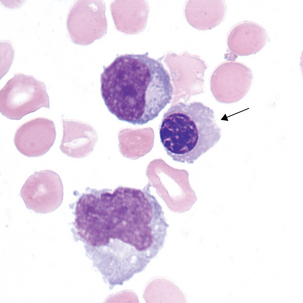

2.Erythrophages—identifiable from 1 to 7 days

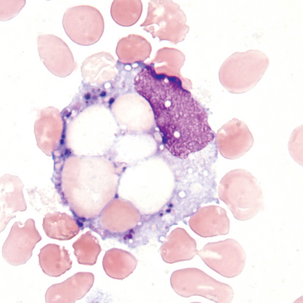

3.Hemosiderin and siderophages—observable from 2 days to 2 months

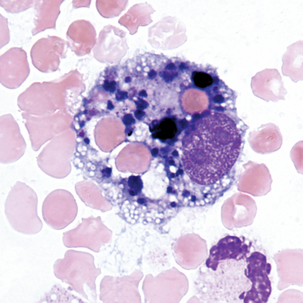

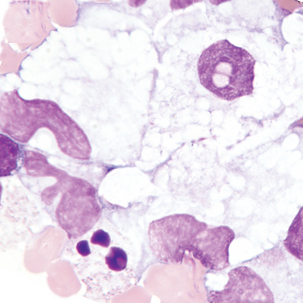

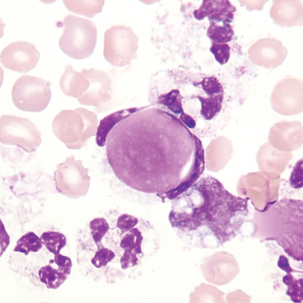

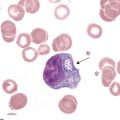

Macrophage with engulfed RBCs. RBCs are digested by enzymatic activity within the macrophage. The digestion process causes the RBCs to lose color and to appear as vacuoles within the cytoplasm of some macrophages.

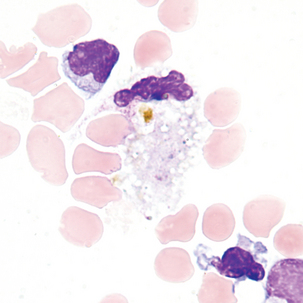

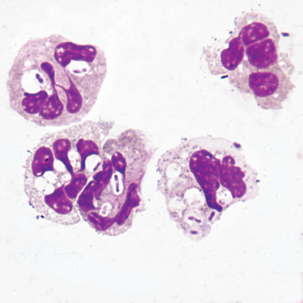

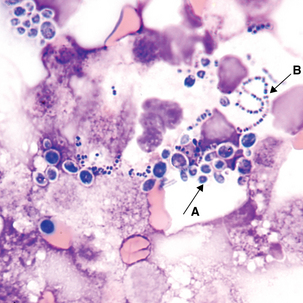

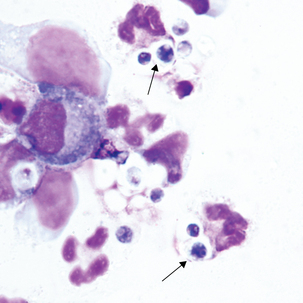

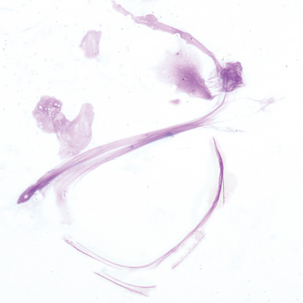

Organisms sometimes found in cerebrospinal fluid

CSF is a sterile body fluid. Following are examples of some organisms that have been seen in CSF, but it is far from an all-inclusive list of possibilities (Figures 24-12 to 24-14). Note that organisms may be intracellular, extracellular, or both.

Cells sometimes found in serous body fluids (pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal)

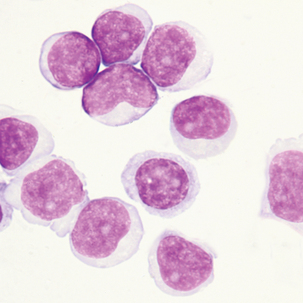

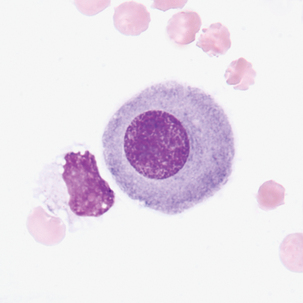

Description

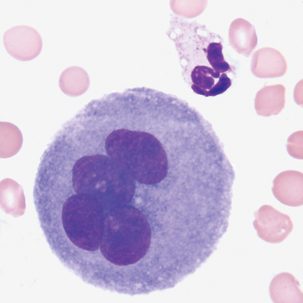

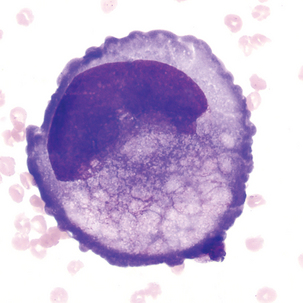

Round to oval cell with eccentric nuclei, dark blue cytoplasm, perinuclear hof 8-29 μm in diameter.

Associated with:

Rheumatoid arthritis, malignancy, tuberculosis, and other conditions that exhibit lymphocytosis

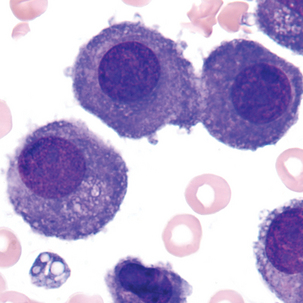

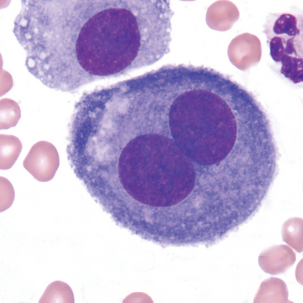

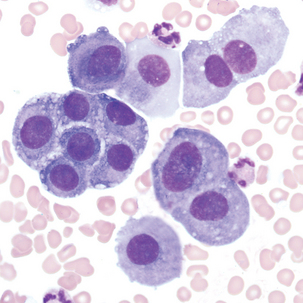

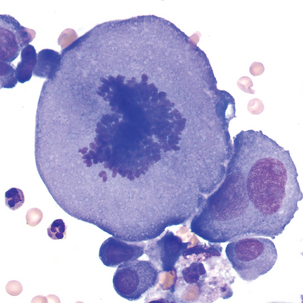

Multinucleated mesothelial cells

Cytoplasm:

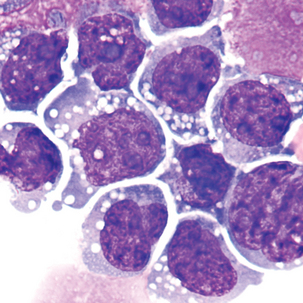

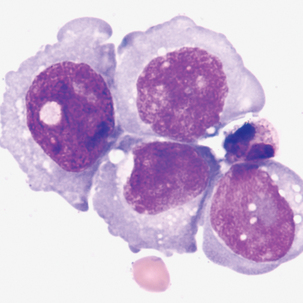

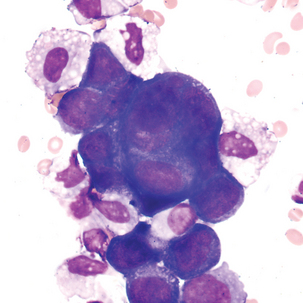

Smears with cells displaying one or more of the above characteristics should be referred to a qualified cytopathologist for confirmation. See Table 24-1 for a comparison of benign and malignant features. Malignant cells tend to form clumps with cytoplasmic molding. The boundaries between cells may be indistinguishable.

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Occasional large cells | Many cells may be very large |

| Light to dark staining | May be very basophilic |

| Rare mitotic figures | May have several mitotic figures |

| Round to oval nucleus; nuclei are uniform size with varying amounts of cytoplasm | May have irregular or bizarre nuclear shape |

| Smooth nuclear edge | Edges of nucleus may be indistinct and irregular |

| Nucleus intact | Nucleus may be disintegrated at edges |

| Nucleoli are small, if present | Nucleoli may be large and prominent |

| In multinuclear cells (mesothelial), all nuclei have similar appearance (size and shape) | Multinuclear cells have varying sizes and shapes of nuclei |

| Moderate to small N:C ratio | May have high N:C ratio |

| Clumps of cells have similar appearance among cells, are on the same plane of focus, and may have “windows” between cells | Clumps of cells contain cells of varying sizes and shapes, are “three-dimensional” (have to focus up and down to see all cells), and have dark staining borders; no “windows” between cells |

N:C, Nuclear:cytoplasmic.

From Rodak BF, Fritsma GA, Keohane EM: Hematology: clinical principles and applications, ed 4, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.

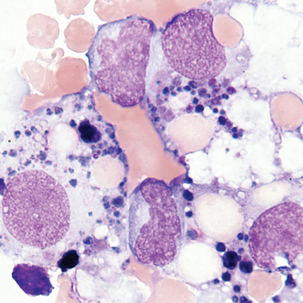

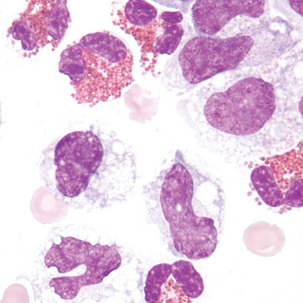

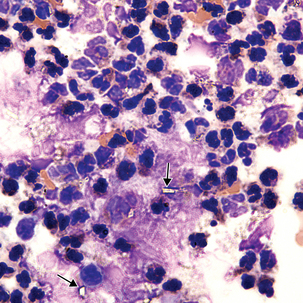

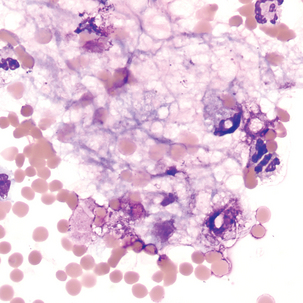

Malignant cells sometimes seen in serous fluids

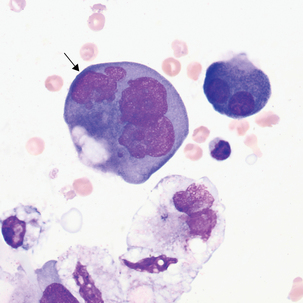

FIGURE 24–26 Malignant tumor (pleural fluid × 500). Note molding of cytoplasm (no “windows” between cells).

FIGURE 24–27 Adenocarcinoma, metastases from uterine cancer (pleural fluid ×500). Note irregular nuclear membranes.

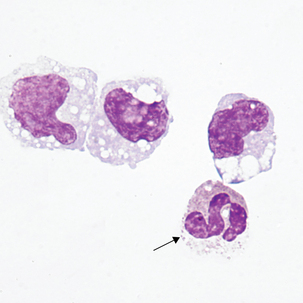

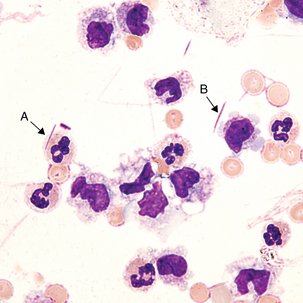

Mitotic figures may be found in normal fluids and are not necessarily an indication of malignancy. The size of this mitotic figure, however, is quite large, and malignant cells were easily found.

Crystals sometimes found in synovial fluid

Cells that may be found in normal synovial fluids include lymphocytes, monocytes, and synovial cells. Synovial cells, which line the synovial cavity, resemble mesothelial cells (see Figure 24-19) but are smaller and less numerous. Increased numbers of polymorphonuclear neutrophils may be seen in bacterial infection and acute inflammation. When neutrophils are seen, a careful search for bacteria should be performed. Tumor cells are possible but quite rare. LE cells may also be seen (see Figure 24-18).

Associated with:

FIGURE 24–31 Monosodium urate crystals (synovial fluid ×1000; unstained).

(Courtesy George Girgis, MT [ASCP], Indiana University Health.)

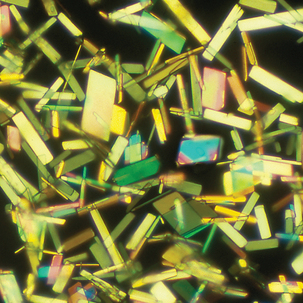

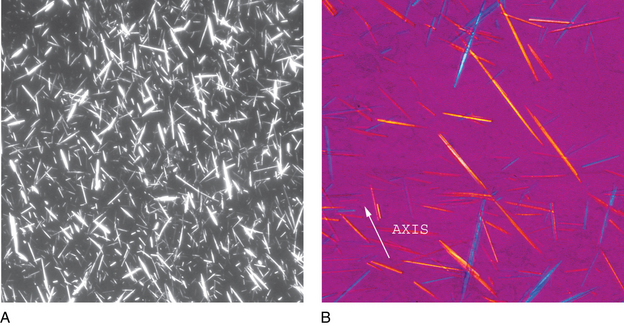

FIGURE 24–32 Monosodium urate crystals, polarized light microscopy (A) and with red compensator (B) (synovial fluid ×1000).

(Courtesy George Girgis, MT [ASCP], Indiana University Health.)

Note the orientation of the crystals and corresponding colors. Crystals appear yellow when parallel to the axis of slow vibration and blue when perpendicular to the axis.

Rhomboid, rod-like chunky crystals may be intracellular, extracellular, or both.

Associated with:

Pseudogout or pyrophosphate gout

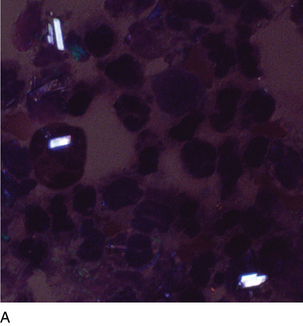

FIGURE 24–34A Calcium pyrophosphate crystals, polarized light microscopy (synovial fluid ×1000).

(Courtesy George Girgis, MT [ASCP], Indiana University Health.)

FIGURE 24–34B Calcium pyrophosphate crystals, polarized with red compensator (synovial fluid ×1000).

(Courtesy George Girgis, MT [ASCP], Indiana University Health.)

Note the orientation of the crystals and corresponding colors. Crystals appear blue when parallel to the axis of slow vibration or yellow when perpendicular to the axis. Calcium pyrophosphate is only weakly birefringent, so that the colors are not as bright as monosodium urate crystals (see Figure 24-32).