10 Bleeding in early pregnancy

Miscarriage

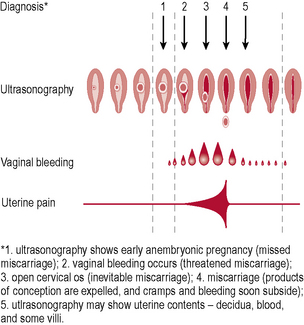

Types of miscarriage (Fig. 10.1)

• Threatened – uterine bleeding without dilatation of cervix or passage of products of conception (POC). The fetus is still viable and the uterus is the expected size for dates. Only one-quarter of these will go on to miscarry.

• Inevitable – heavy bleeding with cervical dilatation, but without passage of POC. The fetus may still be alive, but miscarriage will occur.

• Incomplete – bleeding with cervical dilatation and passage of some, but not all, POC.

• Complete – bleeding which diminishes with complete passage of POC. Pain and bleeding ease, uterus returns to normal size and cervix is closed.

• Missed – fetal death, bleeding or pain; the fetus or embryo has been dead for some weeks, but no tissue has been passed. This is often not recognized until bleeding occurs, the patient complains that she feels ‘less pregnant than before’ and an ultrasound has been performed confirming fetal demise.

• Septic – any of the above that becomes infected, resulting in endometritis and often parametritis and peritonitis.

Management

Therapeutic abortion

Legal aspects of pregnancy termination

A. Endanger the life of the woman

B. Endanger the physical or mental well-being of the woman

C. Endanger the physical or mental well-being of the children of the pregnant woman

D. Involve substantial risk that the child would suffer physical or mental handicap.

The vast majority of terminations are performed for reason B.

Methods of termination

1. Suction curettage is most commonly performed prior to 12–14 weeks’ gestation. The cervix must be dilated and often in nulliparous patients the cervix is ‘ripened’ prior to the procedure with a prostaglandin pessary for ease of dilatation.

2. Antiprogesterone tablets (RU486) are effective up to 9 weeks’ gestation when taken in conjunction with a prostaglandin pessary so that anaesthesia can be avoided.

3. Dilatation of the cervix and evacuation of the uterine contents can be performed after 12 weeks’ gestation until 16–20 weeks. This involves dilatation of the cervix and destruction of the fetal parts followed by evacuation of the uterine contents.

4. Prostaglandin induction is used after 14–16 weeks’ gestation and an oxytocin infusion may also be necessary to expedite what can sometimes be a long, arduous and painful process. Antiprogesterone tablets can be administered 48 hours beforehand to improve the efficacy of this procedure.

Recurrent miscarriage

Aetiology

This will depend on the gestation at which the miscarriage occurs.

Investigations

Ectopic pregnancy

Definition

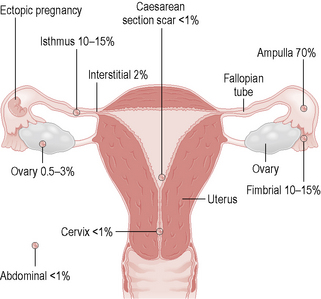

An ectopic pregnancy is when the embryo implants outside the uterine cavity. The most common site is in the fallopian tube, although implantation can occur in the cornua of the uterus, the cervix, ovary or abdominal cavity (Fig. 10.2). These sites are unable to contain the growing trophoblast and embryo, so rupture may occur, leading to catastrophic bleeding.

Aetiology

• Previous pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 10-fold). The recent increase in PID is thought to have contributed to the increased incidence of ectopic pregnancy.

• Previous tubal surgery, including reconstruction and sterilization (increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 4½-fold).

• Previous ectopic pregnancy (10-fold). Even if a tube has been previously removed, the initial causative pathology is often bilateral.

• Assisted reproductive techniques (in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer).

• Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD). This is a risk if pregnancy occurs whilst in situ. Most current contraceptive methods protect against ectopic pregnancy except when the method fails. However, modern copper-bearing IUCDs (Copper T 380, Multiload Cu 375) and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) are extremely effective contraceptives with failure rates of around 1 in 100 after 5 years of use, making them acceptable contraceptive choices for women with a previous history of ectopic pregnancy.

Assessment

• A history of pain, irregular scanty bleeding and amenorrhoea

• General examination of vital signs, evidence of acute abdomen, cervical excitation with a bulky uterus and a tender adnexae on vaginal assessment

• Checking for the presence of βhCG, which is detected in the urine as early as 14 days postconception or in the serum 5–9 days postconception by sensitive assays. Between 2 and 4 weeks after ovulation serum βhCG levels double approximately every 2 days in a normal intrauterine pregnancy; a lesser increase (<66% over 48 hours) is associated with ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. In order to increase the sensitivity of quantitative βhCG, a discriminatory zone has been described whereby a titre of 1000–1500 IU/l (international reference preparation) will be associated with the presence of an intrauterine sac on transvaginal ultrasound

• Transvaginal ultrasound: positive signs of an intrauterine pregnancy on ultrasound scan include a gestation sac (at approximately 4 weeks’ amenorrhoea), the double decidual sign (at 5 weeks), the yolk sac (5–6 weeks) and, finally, the fetal heartbeat (7 weeks). Ectopic pregnancy should be suspected if there are ultrasonic appearances of an empty uterus, an intrauterine pseudosac, evidence of a tubal swelling or ring sign with a fetal heartbeat, or fluid in the pouch of Douglas. Demonstration of a viable intrauterine pregnancy does not exclude the possibility of heterotopic pregnancy (frequency 1/30 000–40 000 spontaneously to 1–3% after assisted reproduction), i.e. a coexisting ectopic and intrauterine pregnancy.

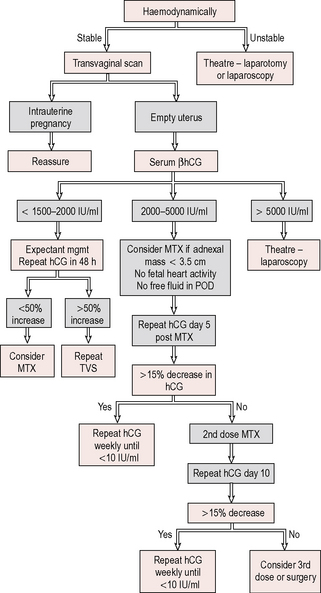

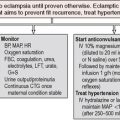

Management

If an ongoing ectopic is suspected, the patient should be admitted to hospital for further investigation, with blood taken for crossmatching and intravenous access (Fig. 10.3).

Surgical treatment

• Linear salpingotomy can be performed for an ampullary ectopic and fimbrial expression for an ectopic that is extruding from the fimbrial end. Salpingotomy is a reasonable approach when there is only one tube, but is associated with a 20% rate of further ectopic.

• Salpingectomy is preferred to salpingotomy when the contralateral tube is healthy as it is associated with a lower rate of persistent trophoblastic tissue, lower subsequent ectopic pregnancy and a similar subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rate. Salpingectomy is also indicated in the presence of uncontrolled bleeding, a second ectopic in the same tube, a severely damaged tube and occasionally when childbearing is complete.

• If patient is haemodynamically compromised or the surgeon has little experience in laparoscopic surgery, then a laparotomy is a reasonable approach.

Gestational trophoblastic disease

Definitions

A hydatidiform mole is a benign tumour of the trophoblast and can be either partial or complete.

Summary

• Detailed history and examination are vital in the assessment of early-pregnancy bleeding.

• Transvaginal ultrasound assessment is a key part of the assessment of early-pregnancy complications.

• Ectopic pregnancy should always be considered, as the presentation is highly variable and the consequences can be devastating if diagnosis is missed.

• Pregnancy loss is highly emotive and psychological support should always be offered.

• Patients with recurrent pregnancy loss must be fully investigated, as causes such as APS can be managed successfully.

• Cases of gestational trophoblastic disease must be registered at regional centres, as follow-up of these patients is vital.