Chapter 7 BLEEDING AND BRUISING

General Discussion

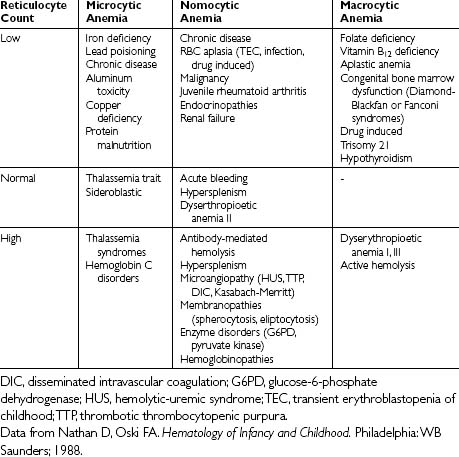

Initial laboratory tests are outlined below. It is important that results are compared against age-specific ranges because test results and coagulation factor levels vary with age. The pattern of abnormalities obtained using first line tests in association with the clinical presentation and history may indicate an underlying disorder (Table 7-1). However, some significant bleeding disorders may have normal test results. Conversely, some abnormal results are not associated with bleeding.

Table 7-1 Patterns of Coagulation Results and the Differential Diagnosis

| Test Results | Differential Diagnosis | Possible Follow-up Laboratory Studies |

|---|---|---|

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia purpura; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PT, prothrombin time; TCT, thrombin clot time: TPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

From Allen GA, Glader B. Approach to the bleeding child. Pediatr Clin North Am 2002;49:1239–1256, with permission.

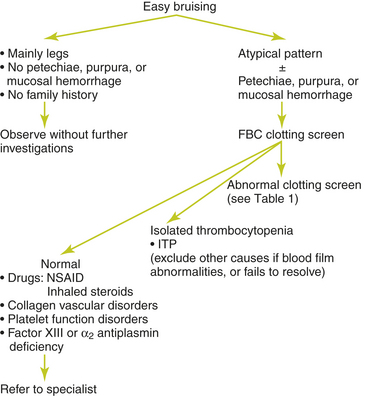

A thorough history is the most important step in establishing the presence of a hemostatic disorder and in guiding initial laboratory testing. Figure 7-1 provides an approach to investigation of easy bruising or bleeding.

Causes of Bleeding

• Acquired factor VIII inhibitors

• Amegakaryocyctic thrombocytopenia

• Congenital factor deficiencies

• Disseminated intravascular coagulation

• Drug related thrombocytopenia

• HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome

• Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn

• Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

• Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

• Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency

• Platelet storage pool disorder

• Post-transfusion purpura syndrome

• Rat poison ingestion (superwarfarins)

• Sepsis, especially meningococcal

• Systemic lupus erythematosus

Key Historical Features

Mucous membrane bleeding (menorrhagia, epistaxis, gum bleeding)

Mucous membrane bleeding (menorrhagia, epistaxis, gum bleeding)

Bleeding response to injury such as a bitten tongue

Bleeding response to injury such as a bitten tongue

Bleeding into soft tissues such as muscles and joints

Bleeding into soft tissues such as muscles and joints

Excessive bleeding during surgical procedures (circumcision, tonsillectomy, tooth extraction), fractures, or serious injuries

Excessive bleeding during surgical procedures (circumcision, tonsillectomy, tooth extraction), fractures, or serious injuries

History of cephalohematoma, unexpected bleeding from the umbilical stump, or bruising after intramuscular injections

History of cephalohematoma, unexpected bleeding from the umbilical stump, or bruising after intramuscular injections

Menstrual and obstetric history in female patients

Menstrual and obstetric history in female patients

Family history of bleeding, including grandparents and the extended family

Family history of bleeding, including grandparents and the extended family

Key Physical Findings

Suggested Work-up

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | To evaluate for thrombocytopenia and anemia |

| Peripheral blood smear | To evaluate the cell lines and confirm thrombocytopenia |

| Prothrombin time (PT) | To evaluate plasma coagulation function |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) | To evaluate plasma coagulation function |

| Fibrinogen measurement | To evaluate the functional activity of fibrinogen |

Additional Work-up

| Factor VIII, factor IX, von Willebrand factor antigen and activity (Ristocetin cofactor) | Recommended in all cases of non-accidental injury |

| Mixing study | To evaluate an abnormal PT or aPTT. Normalization of the PT or aPTT following a mixing study indicates a factor deficiency |

| Coagulation-factor assays (factors VIII, IX, and XI) | Indicated when a factor deficiency is suggested by mixing studies or family history |

| Factor VII assay | If there is an isolated prolongation of the PT to evaluate for vitamin K deficiency or liver disease |

| Thrombin time and reptilase time | Indicated if there is an isolated prolongation of the aPTT and heparin contamination from the catheter is suspected. Prolongation of the thrombin time with normal reptilase time is suggestive of heparin contamination. If both the thrombin time and reptilase time are prolonged, the most likely cause is a low fibrinogen concentration |

| Thrombin time | Used when both the PT and aPTT are prolonged to test for fibrinogen conversion to fibrin. When the thrombin time is prolonged, it signifies low fibrinogen activity, the presence of fibrin split products, or heparin contamination |

| Factor VIII, von Willebrand factor antigen, von Willebrand factor activity (ristocetin cofactor assay), and factor IX assay | If von Willebrand disease is suspected |

| PFA-100 platelet function screen | A newer substitute for the bleeding time. The time to occlusion is prolonged in patients with most types of von Willebrand disease and some platelet disorders |

| PT, aPTT, thromboplastin time, thrombin time, platelet count, factor VIII assay, factor V assay, fibrinogen, and D-dimer | If disseminated intravascular coagulation is suspected |

1. Allen G.A., Glader B. Approach to the bleeding child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:1239–1256.

2. Ewenstein B.M. The pathophysiology of bleeding disorders presenting as abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:770–777.

3. Handin R.I. Bleeding and thrombosis. In: Isselbacher K.J., Braunwald E., Wilson J.D., editors. Harrison’s Textbook of Internal Medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994:317–322.

4. Lusher J.M. Screening and diagnosis of coagulation disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:778–783.

5. McKenna R. Abnormal coagulation in the postoperative period contributing to excessive bleeding. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:1277–1310.

6. Thomas A.E. The bleeding child; is it NAI? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1163–1167.

7. Vora A., Makris M. An approach to investigation of easy bruising. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:488–491.