Chapter 19 Bladder Cancer and Upper Tracts

Epidemiology And Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Bladder cancer is the most common tumor of the urinary tract. In the United States, it is the fourth most common malignancy in males, accounting for 7% of all male malignancies. There will be an estimated 70,530 new cases and 14,680 deaths from bladder cancer in the United States in 2010.1 The peak incidence is in the ninth decade, although there is a suggestion of a trend toward presentations at a younger age. The incidence is four times higher in men than in women. The lifetime risk for men is 3.8% and for women is 1.2%.1 The tumor is twice as common in whites as in African Americans. In the United Kingdom, bladder cancer is overall the seventh most common malignancy, with an age-standardized rate of 11.4 per 100,000.2

The incidence of upper tract disease is less easily estimated because cancer registries tend to include primary PC system tumors as “renal” cancers. If one makes the assumption that 15% of such “renal” tumors are of PC system origin, there will be 8740 new cases and 1960 deaths from renal pelvic cancer in the USA in 2010.1 There will be an estimated 2490 new cases and 830 deaths from ureteric cancer in the United States in 2010.1 Ureteral transitional cell cancer (TCC), like bladder cancer, is more common in men than in women (ratio 2:1), and the incidence peaks in the eighth decade of life.

For patients with a bladder cancer, up to 6.4% will develop upper tract tumors.3,4 Conversely, for patients with upper tract tumors, up to 40% will develop lower tract disease.5

Risk Factors

Reported risk factors for urothelial tumors include exposure to aniline, aromatic amines, diesel fumes, phenacetin abuse, cigarette smoking, arsenic, and living in urban areas. Heavy smokers (>40 pack-yr) are five times more prone to develop TCC than nonsmokers.6 Balkan nephropathy, an endemic degenerative interstitial nephropathy in Eastern Europe of unknown etiology, is associated with 100 to 200 times the risk of upper tract TCC. These tumors are typical multifocal, but of low grade.7,8 Coffee drinking and artificial sweeteners have been considered to be possible risk factors, but these have not been fully substantiated as a cause of this malignancy.9

Genetic factors in the etiology of urothelial tumors are emerging, and these may be associated with the aggressiveness of the tumor, such as tumor grade, stage, and propensity for vascular invasion.10

Adenocarcinomas of the bladder mucosa are associated with a persistent urachal remnant and cystitis glandularis (which is associated with bladder extrophy).11 In addition, micropapillary and small cell tumors have been reported and are signs of an aggressive histology associated with worse outcomes, likely as a result of early micrometastases.12,13 The rarity of these two histologies has limited our abilities to determine definitive associations; their frequent finding in combination with TCCs would lead one to expect an association with carcinogen exposure.

Anatomy and Pathology

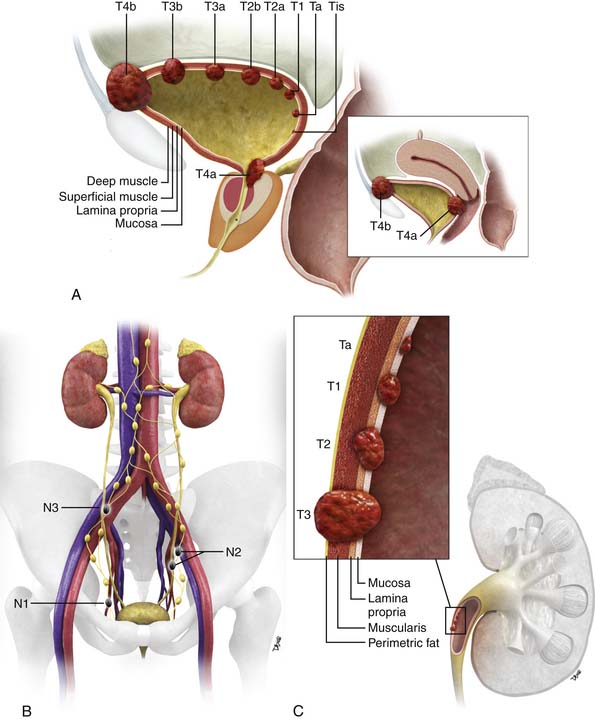

The urinary collecting system conveys, stores, and delivers urine to the exterior of the body; it extends from the renal collecting system and calyces, renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, and urethra. The epithelium of the entire collecting system, the urothelium, consists of the same cell type, transition cells. Deep to the urothelium is a layer of connective tissue and irregularly arranged smooth muscle fibers, frequently considered the submucosa (although strictly this term is incorrect because there is no muscularis mucosae). Deep to the submucosa are three layers of muscle (internal or superficial longitudinal, middle circular, and external or deep longitudinal). Deep to all of these layers is the perivesical or periureteral fat or, toward the dome of the bladder, a partial serous coat derived from the peritoneum (Figure 19-1A).

Figure 19-1 Bladder staging. Schematic of T stage (A) and N stage (B). C, Upper tract staging: schematic of T stage.

The vast majority of tumors that affect the urinary collecting system are epithelial in origin and are termed urothelial carcinomas. The vast majority of these tumors are of TCC origin (>90%); other subtypes are squamous cell (5-10%), adenocarcinoma (2-3%), and small cell carcinoma (<1%).11 TCCs have a propensity to develop in multiple locations throughout the urothelium, both upper tracts and lower tracts. Adenocarcinomas may be mucin-secreting.

Other extremely rare tumors include leiomyoma, hemangioma, granular cell tumors, neurofibroma, paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors (e.g., non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), carcinosarcoma, malignant melanoma, metastases, and direct invasion from adjacent organs.11

Bladder

The majority of superficial tumors, which are limited to the mucosa and lamina propria, tend to be papillary (i.e., projecting into the lumen) and of low histologic grade. They tend to carry a good prognosis, although they have a propensity to recur (70% at 3 yr), and 10% to 20% may progress to invasive disease (although this is as high as 46% in patients with T1 disease).14 Seventy percent of patients with superficial tumors have low-grade papillary tumors, and 30% have higher-grade, flat, carcinomas in situ. Flat carcinomas in situ carry a higher risk of progression and invasion.15

Upper Tracts

In the ureter, the frequency distribution of urothelial tumors is distal (73%), mid (24%), and proximal (3%). Bilateral disease may occur in 2% to 5% of cases. The tumors are histologically similar to those in the bladder.16 As with urothelial tumors in the bladder, upper tract tumors may be superficial (85%) or infiltrating (15%).

Key Points Anatomy and pathology

• The whole of the urinary collecting system is lined by urothelium.

• The “upper” urinary collecting tract is considered to be calyces, renal pelvis, and ureter; the “lower tract,” bladder and urethra.

• The whole urothelium is potentially at risk of tumor once a tumor is found in any location.

• Most common urothelial tumor is TCC (>90%).

• Urothelial tumors may be superficial (70%) or infiltrative (30%).

• Infiltrative tumors are generally of higher histologic grade and more aggressive.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Bladder

Disease may spread lymphatically, typically in a contiguous fashion from pelvic (internal iliac, obturator, and external iliac) to common iliac and retroperitoneal nodes. In advanced disease, lymphatic spread may extend above the diaphragm to mediastinal, hilar, and cervical nodes. The incidence of nodal metastasis is approximately 30% in tumors that involve the bladder wall and approximately 60% in those with extravesical invasion.17 Nodal staging has an important impact on prognosis.

The tumor may also metastasize hematogenously, with the liver being the most common site for metastatic disease, followed by bones and lungs.18

When seen, in males, TCC of the urethra is commonly found in the prostatic urethra.

Upper Tracts

Primary urothelial tumors in the upper tracts spread locally to involve periureteral and peripelvic fat. In the region of the renal pelvis, urothelial tumors can infiltrate into the renal parenchyma, where unlike primary renal tumors, they tend to preserve the contour of the kidney. Infiltrating tumors of the ureters tend to be more aggressive than those in the bladder, probably because of the thinner wall of the ureter.19,20

Staging Evaluation

Bladder

The two main staging classification systems for tumors are (1) the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM; Tables 19-1 and 19-2) and (2) the Jewett-Strong-Marshall classification (Table 19-3). The TNM staging system is the more widely used and comprehensive. T stage mainly describes the depth of local bladder wall invasion of the tumor as related to normal bladder wall layers. N stage is based on the size and number of nodes involved by metastatic disease. M stage describes whether there are disseminated hematogenous metastases or not. Retroperitoneal adenopathy is classified as M stage disease.

Table 19-1 Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging for Bladder Cancer by the American Joint Committee on Cancer

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT |

|---|---|

| T Stage | |

| Ta | Noninvasive papillary carcinoma, confined to urothelium and projecting toward lumen |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: flat tumor, high-grade histologic features confined to urothelium |

| T1 | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue (lamina propria) |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscle |

| T2a | Tumor invades superficial muscle (inner half) |

| T2b | Tumor invades deep muscle (outer half) |

| T3 | Tumor invades perivesical tissue |

| T3a | Tumor invades perivesical tissue microscopically |

| T3b | Tumor invades perivesical tissue macroscopically (extravesical mass) |

| T4 | Tumor invades prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, or abdominal wall |

| T4a | Tumor invades prostate, uterus, or vagina |

| T4b | Tumor invades pelvic wall or abdominal wall |

| N Stage | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastasis to single lymph node < 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis to single lymph node 2-5 cm in greatest dimension or multiple lymph nodes none > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| M Stage | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Suffix “is,” associated carcinoma in situ; suffix “m,” multiple tumors.

From Bladder cancer. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:569-577.

Table 19-2 Staging for Bladder Cancer, with Tumor-Node-Metastasis Equivalent

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT | TNM CLOSEST EQUIVALENT |

|---|---|---|

| 0a | Papillary, noninvasive | Ta, N0, M0 |

| 0is | Carcinoma in situ, noninvasive | Tis, N0, M0 |

| I | Invades subepithelial connective tissue | T1, N0, M0 |

| II | Invades muscle layer | T2, N0, M0 |

| III | Extravesical spread | T3 or T4a, N0, M0 |

| IV | Fixed to or invading prostate, uterus, vagina or pelvic lymph nodes | T4b, N0, M0 or any T, N1 to 3, M0, or any T, any N, M1 |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From Bladder cancer. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:569-577.

Table 19-3 Comparison of AJCC and Jewett-Strong-Marshall Staging Systems

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT | TNM CLOSEST EQUIVALENT |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Limited to mucosa, flat in situ or papillary | Tis, Ta |

| A | Lamina propria invaded | T1 |

| B1 | < halfway through muscularis | T2a |

| B2 | > halfway through muscularis | T2b |

| C | Perivesical fat, prostate, uterus or vagina, pelvic wall or abdominal wall | T3, T4a, T4b |

| D1 | Pelvic lymph node(s) involved | N1-N3 |

| D2 | Distant metastases | M1 |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Training Modules Staging: Comparison of AJCC & Jewell-Strong-Marshall Staging Systems. Available at http://training.seer.cancer.gov/bladder/abstract-code-staging.html (accessed October 27, 2011).

A schematic of the TNM T staging is presented in Figure 19-1A and B. Superficial tumors are considered Tis, Ta, and T1; infiltrative tumors are T2, T3, and T4.21,22

Prognosis worsens with increasing T, N, and M stage and higher classes of Jewett-Strong-Marshall staging. The overall 5-year survival is 97.2%, 74.3%, 36.2%, and 5.8%, for in situ, localized, regional, and distant disease, respectively.23 Nodal status and organ confinement are independent predictors of survival.24

Prognosis is also affected by tumor grade, the presence of vascular and lymphatic invasion, and diffuse carcinoma in situ (CIS). Of note, these latter factors are not currently reflected in staging classifications.25

Treatment options are influenced by tumor stage. Clinical staging can underestimate the extent of disease in up to 50% of cases as compared with pathology.25 Imaging has the potential to improve this.

Upper Tracts

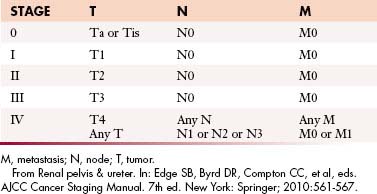

The TNM staging system for urothelial tumors of the upper tracts is presented in Tables 19-4 and 19-5. As with bladder staging, T staging of the upper tracts is assessed in

Table 19-4 Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging of Upper Urinary Tract Transitional Cell Carcinoma

| TNM STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT |

|---|---|

| Ta | Noninvasive papillary carcinoma, confined to urothelium and projecting toward lumen |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: flat tumor, high-grade histologic features but confined to urothelium |

| T1 | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue (lamina propria) |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis |

| T3 | Renal pelvis: Tumor invades beyond muscularis into peripelvic fat or renal parenchyma. Ureter: Tumor invades beyond muscularis into periureteric fat |

| T4 | Tumor invades adjacent organs, pelvic or abdominal wall, or through kidney into perinephric fat |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastasis to single lymph node < 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis to single lymph node 2-5 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple lymph nodes, none > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From Renal pelvis & ureter. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:561-567.

relation to depth of invasion into the various layers of the wall of the ureter (see Figure 19-1C).

Imaging

Primary Tumor (T)

Bladder

In low T stage disease, cystoscopy and deep biopsy with histologic evaluation is the standard of care. For more deeply invasive tumors (stage T3, T4), clinical staging, which includes bimanual examination under anesthesia to assess the bladder mass and fixity to adjacent organ, has reported errors of both under- and overstaging, of 25% to 50%.26–29 Imaging plays a role in the evaluation of such tumors, especially for nodal and hematogenous metastatic disease.

Computed Tomography

Technique

Thin-section rapid scanning in the portal venous phase at 60 to 80 seconds after commencement of intravenous (IV) contrast medium (125-150 mL at 2.5-3.0 mL/sec) allows detection of tumor enhancement in the bladder wall before excreted IV contrast medium reaches the bladder. Delayed images (180 sec) allow detection of soft tissue density masses against the background of IV contrast within the bladder lumen. Thin-section acquisition allows multiplanar re-formations. Oral and rectal contrast media assist in delineation of adjacent organs in the pelvis. The bladder should be moderately distended. Care should be taken not to over- or underdistend the bladder because the former may flatten small tumors and underdistention may result in spurious bladder wall thickening. If a urinary catheter is in place, it should be clamped for a period before and during the examination.

Findings

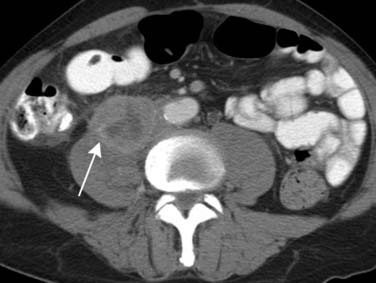

Urothelial tumors in the bladder may appear as foci of thickening in the wall or as filling defects, which may be polypodial (Figure 19-2). Fine calcification may be seen on the mucosal surface. The lesions may demonstrate early enhancement after IV contrast media infusion, probably a reflection of angiogenic activity in the tumor (Figure 19-3). CT is unable to resolve the various bladder wall layers and is, therefore, unable to resolve low T stage disease. Retraction of the outer bladder wall at the site of the tumor is suggestive of deep muscle involvement (stage T2b).

Tumors close to the vesicoureteric junction may cause ureteric obstruction, which may be a presenting feature of the disease (Figure 19-4). Tumors may also be detected in bladder diverticulae, which importantly may not be visible on cystoscopy (Figure 19-5).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Findings

The signs of bladder tumors are similar to those on CT. Tumors are usually hyperintense to muscle on T2-weighted images and isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images (Figure 19-6A). On occasion, the combination of T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images can help to delineate between stages T2a and T2b tumors, with preservation of T2-weighted hypointensity of bladder muscle adjacent to enhancing tumor.

The corresponding findings of T3b disease described previously for CT appear as hypointense nodules or stranding within the T1-weighted and T2-weighted hyperintense perivesical fat (see Figure 19-6A). These findings may be more conspicuous with the use of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed images, in which enhancing tissue is seen in the surrounding hypointense (suppressed) perivesical fat.30

MRI is superior to CT in staging T4 disease because of its better intrinsic contrast resolution and multiplanar capability. For example, the combination of sagittal and axial images on MRI allows good delineation of the rectum and vagina (see Figure 19-6B). It should be noted that abutment of structures does not necessarily indicate invasion, and conversely, involvement cannot be excluded; invasion is more likely if foci of infiltration can be identified.

Overall, studies of CT and MRI suggest that MRI is more accurate in staging with accuracies ranging from 73% to 96% compared with CT accuracies of 40% to 95%. This is largely because of the superior ability of MRI in assessing deep muscle layer involvement and earlier detection of adjacent organ invasion. It should be noted that most reported MRI evaluations have been undertaken with body and not pelvic phase array coils, and MRI accuracy may be improved further with such higher-resolution coils.17,31–49

An important limitation of imaging evaluations of the primary tumor is that bladder wall thickening and contrast enhancement may be due to inflammation, edema, or fibrosis, for example, following biopsy, transurethral resection (TUR), or radiation therapy, and cannot be reliably distinguished from tumor (Figure 19-7). Imaging for local staging is best undertaken before biopsy or resection, but this is not always feasible.29

Ultrasonography

A number of ultrasonographic techniques, such as transabdominal, transuretheral, transvaginal, and transrectal, have been investigated to evaluate bladder tumors. Intravesical ultrasound has been reported to have accuracies for T staging ranging from 62% to 92%.50,51 Ultrasonography has limited general utility because of its general poor visualization of extravesical structures.52

Upper Tracts

Intravenous urography (IVU) is the standard of care technique for evaluating the upper tracts. Direct pyelography is more invasive, but may be undertaken if IVU cannot be undertaken or is indeterminate; it also allows the potential for cytologic evaluation. Computed tomographic urography (CTU) is a technique being developed and increasingly utilized; it has a variety of advantages and disadvantages compared with IVU. Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) is an evolving technique that has some potential advantages compared with CTU but also some relative disadvantages and is still in development.

Intravenous Urography

Imaging Findings

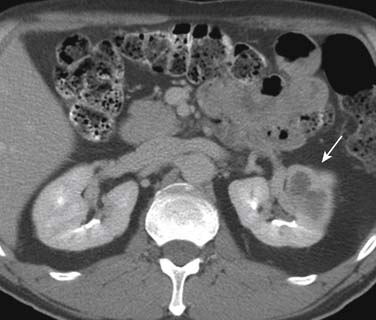

Signs of urothelial tumors in the upper tract include filling defects and strictures, which may be smooth or irregular (Figure 19-8). In the PC system, a stippled appearance may be encountered, which represents contrast medium trapped in papillary fronds of the tumor (see Figure 19-8). Tumors in the region of a calyceal orifice may cause obstruction of the calyx, resulting in lack or delayed excretion of IV contrast medium into that calyx, or “calyceal amputation.” In the ureter or region of the vesicoureteric orifice, tumors may cause ureteric obstruction and hydronephrosis, which may also be associated with delayed or absent excretion of contrast medium. IVU may fail to detect upper tract tumors in as many as 50% to 90% of cases.53,54

Computed Tomography Urography

Technique

Specific protocols are evolving; however, the fundamental requirements are (1) high-resolution scans to allow detection of small filling defects, urothelial wall thickening, and three-dimensional (3D) re-formations and (2) ureteric distention. Current 16- or higher row multidetector CT scanners have the potential for high-resolution axial scans of 1.5 mm or less that can cover the urinary collecting system within a breathhold. A variety of acquisition techniques are under evaluation. Variations focus on methods to try to distend the ureters during imaging, such as abdominal compression, fluid challenge (which may involve IV administration of normal saline), and forced diuresis (with IV furosemide), or a combination. Some techniques employ two separate administrations of IV contrast (“split bolus”).55 Unlike many other CT applications in oncology, positive gastrointestinal contrast media should be avoided because it may complicate subsequent evaluation, particularly the 3D re-formations.

Findings

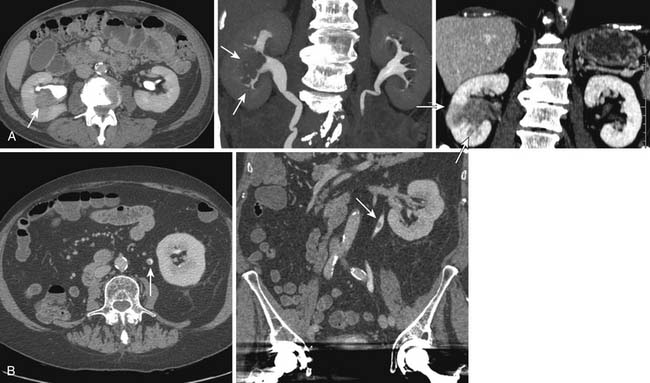

As with the “luminal” (IVU and direct urography) techniques, urothelial lesions may be detected as filling defects or strictures in the upper tracts. However, because of its intrinsic cross-sectional acquisition, CTU has the capability to visualize urothelial wall thickening (Figure 19-9). There is increasing evidence that urothelial wall thickening may be an important sign for urothelial disease; however, the relative importance and accuracy of the signs are yet to be determined.56 TCCs may also appear as fine encrusted calcifications, mimicking renal calculi.

Urothelial tumors in the PC system can be difficult to differentiate from primary renal tumors; the former, however, are typically infiltrative and tend to preserve the contour of the kidney.57 The CT equivalent of calyceal amputation can occasionally be observed (Figure 19-10).

CTU probably has higher sensitivity for detecting upper tract disease than IVU, with a reported pooled sensitivity on meta-analysis of 96%, compared with sensitivities for IVU of 50% to 60%.58–60

CTU is also able to assess for nodal and metastatic disease, thus offering a comprehensive overall evaluation in one examination. An important consideration in the utilization of CTU is its relatively high radiation dose burden, which may be up to 40 mSv.61

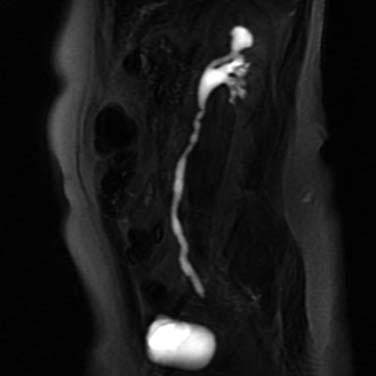

Magnetic Resonance Urography

Technique

Techniques are being developed and evaluated. There are two different MRU approaches, either utilizing IV contrast medium or not. In the latter, the short T2 relaxitivity of urine (water) is leveraged by employing fast T2-weighted sequences, such as SSFSE or Half fourier Acquisition Single shot Turbo spin Echo (HASTE) (Figure 19-11). In techniques relying on intravenously administered MRI contrast agents, images are acquired when contrast is excreted into the collecting systems, using angiographic-type sequences. Advantages of the noncontrast techniques are that the collecting systems can be visualized without the intervention of IV contrast (and the attendant risks of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with renal impairment) and when the system(s) are obstructed or nonfunctioning (because they do not rely on the excretion of intravenously administered contrast media). Both of these techniques are essentially directed at obtaining visualization of luminal features; detecting urothelial wall thickening, which may be an important sign of disease, would require supplementary sequences. Further research is required to optimize these techniques and to determine whether they have the necessary accuracy for lesion detection.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has a very limited role in the detection and evaluation of upper tract tumors. Urothelial tumors in the renal pelvis may appear as soft tissue masses within the otherwise echogenic renal sinus, without or with hydronephrosis. Infundibular tumors may cause focal calyceal dilatation (the equivalent of the amputated calyx on IVU).19

Nodal Disease (N)

Computed Tomography

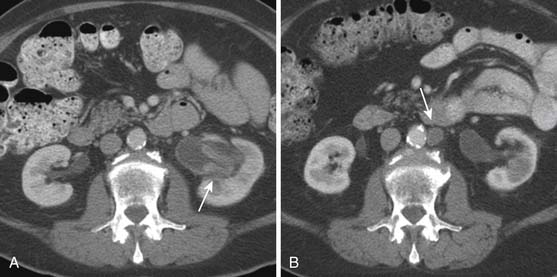

Lymph node size is the main criterion for assessing nodal involvement (Figures 19-12 and 19-13). Unfortunately, as with metastases from other malignancies, small nodes can contain tumor, leading to false-negative results, and enlarged nodes may be reactive and may not contain tumor, causing false-positive results. The challenge of detecting lymph node metastases is compounded because urothelial cancers frequently cause little nodal enlargement.62

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Standard axial (two-dimensional [2D]) CT and MRI have very similar nodal staging accuracies for pelvic tumors in general: reported accuracies for assessing nodal disease in pelvic cancers for CT range from 70% to 97% and for MRI from 73% to 98%.48,63,64 Inevitably, sensitivities and specificities vary according to the nodal cutoff size, with sensitivities increasing and specificities reducing with smaller cutoff dimensions, and vice versa.

There is a suggestion that volumetric rather than planar assessment of the morphology of lymph nodes using 3D MRI techniques may improve accuracy, with rounded nodes being more suspicious than oval nodes. Size cutoff values of 8 mm minimal axial diameter for rounded nodes and 10 mm for flat or oval nodes have reported accuracies of 90%, with positive predictive value of 94%, and negative predictive value of 89% for metastatic disease.65 Identification of abnormal clusters of nodes can also be made. There are also reports that evaluation of the dynamic contrast enhancement characteristics of nodes by MRI may further improve accuracy. The technique uses dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with temporal resolutions of 2 seconds or better and is based on the observation that most metastases, like the primary tumor, enhance more rapidly than normal.30,65

Preliminary reports suggest that lymphographic MRI contrast agents using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO; 20 nm) may improve nodal assessment in bladder and prostatic tumors, with reported sensitivities and specificities of 87% and 92%, respectively.30,65,66

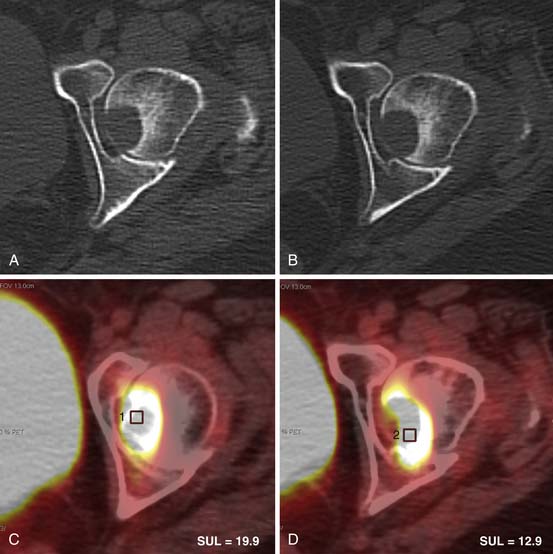

Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose Positron-Emission Tomography

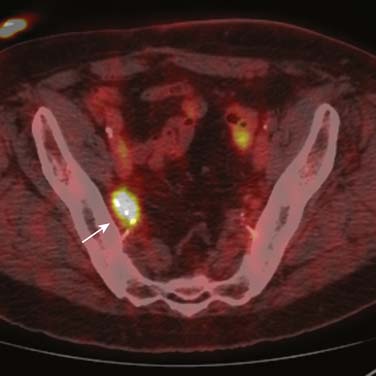

The role of fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)-positron-emission tomography (PET) in urothelial cancers is under evaluation. FDG-PET is of limited value in assessing the primary tumor because of excretion of activity into the entire urinary tract. Metastatic lymph nodes may demonstrate increased FDG avidity (Figure 19-14); however, the combination of the poor spatial resolution of PET and the frequency of small nodes containing metastatic disease limits its utility in general staging.63

Other PET tracers are under investigation, for example, a study with 11C-methionine-PET (which is not renally eliminated) has suggested some correlation with tumor grade, but it did not improve staging accuracy.67

Metastatic Disease (M)

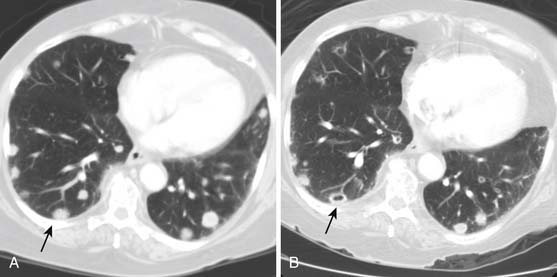

Computed Tomography

Although CT has its limitations in staging of the primary bladder tumor, it is in general the workhorse for screening and staging for nodal and hematogenous metastatic disease for urothelial tumors (Figures 19-15 and 19-16). If more detailed characterization of lesions, for example, in the liver, is required or if contrast-enhanced CT cannot be undertaken, then MRI might be considered.

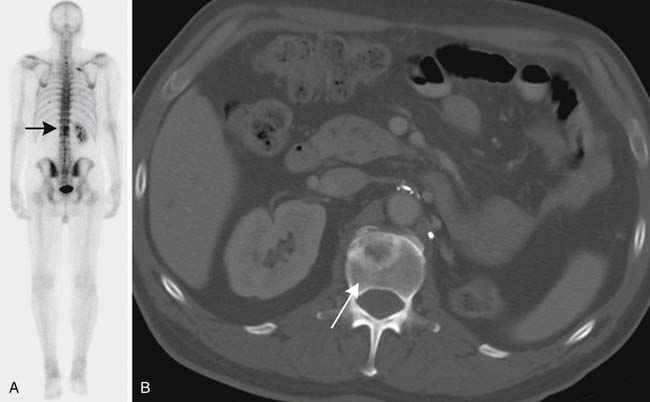

Nuclear Medicine (Other than Positron-Emission Tomography)

Skeletal metastases are relatively uncommon in urothelial tumors, and bone scintigraphy is not generally indicated unless there are relevant symptoms, such as pain. Bone scintigraphy can be supplemented with plain radiography and/or MRI (Figure 19-17).

Percutaneous Biopsy

Key Points Imaging

• MRI is superior to CT in staging of high–T stage bladder cancer.

• CT and MRI have comparable staging accuracies of nodal and hematogenous metastatic disease, although CT is superior for bone and thoracic disease.

• USPIO-MRI is developing as an important imaging adjunct in nodal evaluation.

• The role of PET/CT is undefined, but it may be useful in evaluating residual or recurrent disease.

• Evaluation and screening for upper tract disease is best undertaken by IVU or CTU

Key Points The radiology report, what the surgeon, oncologist, and radiotherapist want to know

• Describe the tumor location and depth of invasion, if possible, and the presence of adjacent organ involvement.

• Presence of synchronous or metachronous urothelial tumors.

• Size and location of suspicious locoregional and more distant lymph nodes.

• Identify location of suspicious metastases.

• Convey overall level of confidence of findings and offer suggestions for other imaging or investigations.

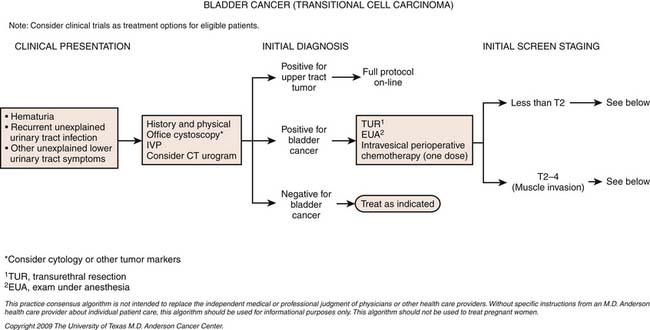

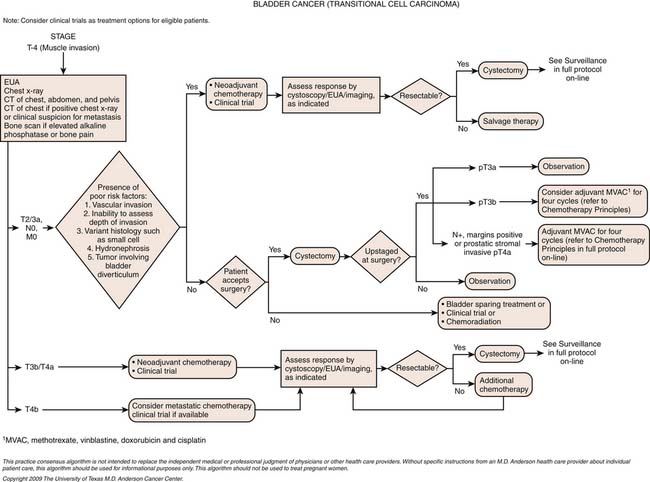

Treatment*

Surgery

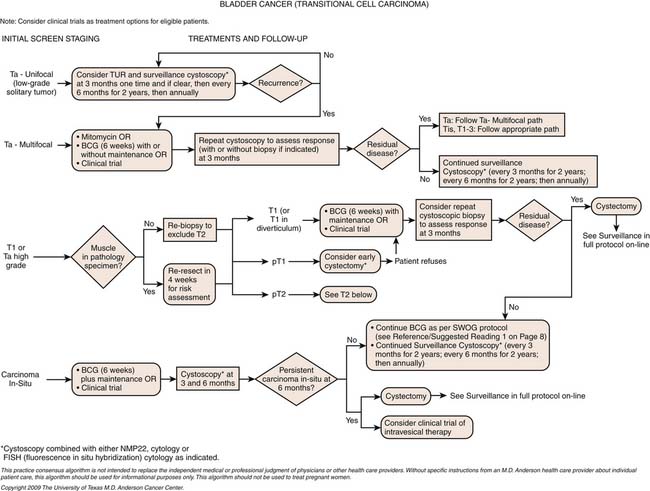

Initial diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder involves cystoscopy with visual identification of an intravesical tumor as well as complete TUR of the tumor. Initial TUR should result in complete resection of all visible tumors and be extensive enough that the specimens should include muscularis propria with a minimum of cautery artifact. In patients who have high-grade tumors resected but no muscle present in the specimen, a repeat resection is recommended. For patients diagnosed with high-risk noninvasive tumors (see definitions later), a second restaging TUR is recommended because upstaging occurs in 49% to 64% of patients with initial apparent T1 lesions. The authors routinely perform the restaging TUR at 4 to 6 weeks to ensure more confident staging and a more accurate gauge of the biology of the disease by identifying tumors with rapid growth potential. This timing also avoids the typical delay of 12 weeks to identify T2 disease; upstaging of many muscle-invasive tumors has been shown with delays greater than 12 weeks.68

Whereas the mainstay of treatment for non–muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder is complete TUR of all visible lesions, up to 70% of bladder tumors recur even with aggressive resection, and as many as 10% to 30% progress. Thus, certain subgroups of patients with bladder cancer have been identified as being at higher risk for recurrence and progression, and they should be considered for intravesical therapy after TUR. These high-risk groups include patients with tumors classified as high grade (which are associated with a 45% risk of progression at 3 yr and the greatest risk of cancer-related death), and patients with CIS (which is associated with a 54% rate of progression to muscle-invasive disease). In addition, irrespective of grade, patients with large lesions (>3 cm), multifocal tumors, evidence of lamina propria invasion, or early recurrence (within 2 yr) have been shown to be at increased risk. In these high-risk groups, aggressive intervention with intravesical therapy leads to response rates up to 85%. However, because even solitary, low-grade, Ta lesions can recur, these must also be considered for adjunctive intravesical therapy, albeit of lesser intensity.69

For patients with invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, with no clinical evidence of metastasis, the first decision required in treatment planning is whether to pursue a radical cystectomy plus lymph node dissection (RC+LND) or a bladder-sparing approach. There is some evidence that a bladder-sparing approach is reasonable in very carefully selected patients (with aggressive TUR, partial cystectomy, or chemoradiation); however, these are used only in very select groups of patients. RC+LND is widely regarded in the United States as the gold standard for the management of invasive bladder cancer.70

Once a patient is considered surgically resectable and able to undergo RC+LND, the next decision is whether to proceed directly to surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or surgery with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The merits and details of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy are subjects of controversy. At M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, an individualized approach is adopted, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy offered to patients considered to be at high risk for occult metastatic disease or those who have a historically poor survival with surgery alone. The latter includes patients with cT3 disease, preoperative hydronephrosis, or presence of features on TUR specimen such as lymphovascular invasion, variant histology (e.g., small cell carcinoma or micropapillary cancer).70,71

Although chemotherapy can be used to augment results of radical cystectomy, it must be emphasized that surgical technique is critical in the management of bladder cancer. Specifically, data demonstrate that the extent of lymphadenectomy and the incidence of positive margins, both critically important in determining outcome, are superior in the hands of experienced surgeons.72 Whereas minimally invasive techniques (e.g., robot-assisted radical cystectomy or laparoscopic assisted radical cystectomy) have been used for this disease, the gold standard, especially for patients with high-risk disease, remains open radical cystectomy.

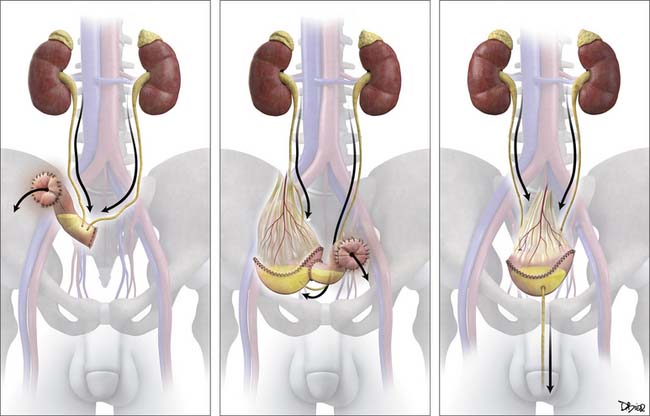

Options for urinary diversion after radical cystectomy include continent orthoptic diversion (neobladder), continent cutaneous diversions (catheterizable pouches), or noncontinent cutaneous diversion (ileal loop stoma) (Figure 19-18).

Intravesical Therapy

For patients with non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer, we recommend complete TUR of all visible disease followed by intravesical instillation of one dose of chemotherapy. The most commonly used intravesical agent in this setting is mitomycin; however, data suggest that most chemotherapeutic agents have similar efficacy. This therapy may be the only treatment necessary for patients with Ta lesions, in whom mitomycin is associated with a 39% decrease in the odds of recurrence. Patients with high-grade or T1 tumors must undergo re-resection as noted previously, following which, they are selected for either intravesical therapy or radical cystectomy based on various parameters.

Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) has been the benchmark against which all other intravesical therapies are compared, since its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1990 for the treatment of CIS of the bladder. The exact mechanism of action of BCG is unknown. BCG attaches to the bladder epithelium, where it is incorporated into the cell, leaving behind surface glycoproteins that are thought to stimulate an immune response. This immune stimulation is nonspecific and includes macrophages, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and a variety of cytokines. Recently, tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand has been implicated as having a role in BCG’s mechanism of action. Intravesical therapy with BCG is performed on an outpatient basis—it is instilled weekly into the bladder of patients via a Foley catheter. The course of therapy is one 6-week induction course followed by maintenance therapy with 3 weeks of BCG at 3 months, 6 months, and then every 6 months for up to 3 years (the Southwest Oncology Group [SWOG] protocol).73 If further recurrence is noted, salvage therapies are available; however, operative intervention with cystectomy should be considered.

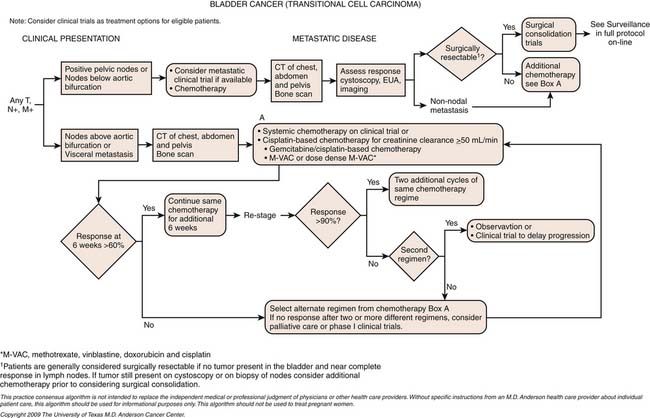

Chemotherapy

The combination of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and cisplatin (M-VAC) has been the gold standard by which other chemotherapy has been compared and is the combination having level 1 evidence showing benefit in the neoadjuvant setting.74–78 Gemcitabine cisplatin has been largely adopted as the standard in the metastatic setting after randomized data suggest equivalent survival but an improved toxicity profile compared with M-VAC.79 A dose-dense modification of M-VAC, in which treatment was given every 2 weeks with growth factor support, showed an improved toxicity profile and improved complete response rate compared with classic M-VAC.80 Although there was no difference in median survival, there was an intriguing improvement in 5 year survival. As a result, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center has adopted the dose-dense approach and are currently studying it on a clinical trial in the neoadjuvant setting.

Upper Tract Therapies

The optimal method of confirming a diagnosis of upper tract urothelial carcinoma is with ureteroscopic evaluation of the lesion. Most of these lesions are classic in appearance and a biopsy is not needed for diagnosis per se. However, a biopsy does help in the decision-making process relating to the type of therapy chosen.81 The main treatment for patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma and a normal contralateral kidney is a complete nephroureterectomy (open or laparoscopic) with removal of a cuff of urinary bladder and regional node dissection. In situations in which there is suspicion for locally advanced disease, we have advocated for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, similar to that used in bladder cancer.

Key Points Therapies

• Superficial bladder tumors can be treated by surgical resection (TURBT).

• Intravesical BCG is a form of local treatment.

• Cystectomy typically includes pelvic lymph node dissection.

• Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapies with a cisplatin-based combination may be employed.

• Upper tract tumors are usually treated by nephrouretectomy, although ureteroscopic resections are becoming possible.

Surveillance

Monitoring Tumor Response

Evaluation of treatment response is essentially based on changes in tumor size, which may be based on the primary tumor or metastatic disease. This can be undertaken by some form of cross-sectional imaging, most commonly CT. For disease limited to the bladder urothelium, cystoscopy may be the only effective way of assessing treatment response.

Detection of Recurrence

The detection of recurrent disease at nodal or visceral sites is best undertaken by some form of cross-sectional imaging, most commonly CT. Prior imaging is probably the most helpful adjunct because increase in size or change in morphology of a node or lesion is the most reliable indicator of new or recurrent disease. Following dissection or irradiation of nodal beds, recurrent disease can appear to “skip” nodal stations (Figures 19-19 and 19-20).

Non–Muscle-Invasive Disease

Other urinary markers include the BladderCheck NMP22 test (Matritech Inc., Newton, MA), which provides for a simple point of care and cheap assay. NMP22 BladderChek is an antibody-based test used to detect a nuclear matrix protein involved in maintenance of nuclear architecture, DNA transcription, and RNA synthesis, which has been highly associated with bladder cancer. The procedure involves placing 4 drops of urine into the disposable device and reading the output 30 to 50 minutes later. The median sensitivity and specificity of NMP22-based testing are 71% (range 47-100%) and 73% (range 55-98%), respectively. A recent study suggests that the NMP22 BladderChek assay may detect tumors not seen initially on cystoscopy and may significantly increase the sensitivity of cystoscopy.82

Metastatic Disease

Key Points Detecting recurrence

• Lower tract recurrences are best detected by cystoscopy.

• Upper tract screening is best undertaken by IVU or CTU.

• Urothelial disease can also be screened by urine cytology.

• Nodal and hematogenous recurrence is best undertaken by CT.

• Increase in size or change in morphology is the most reliable sign of recurrent or residual disease, for which prior imaging is probably the most helpful.

New Therapies

Many chemotherapeutic combinations have shown promise in the treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic urothelial cancer. These include ifosfamide-based combination developed at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center83 and M. D. Anderson Cancer Center84,85; however, use of these in the community may be limited by the typically poor general health and renal function frequently observed in this frail, elderly population of patients. As a result, modified cisplatin,86,87 and nephron-sparing combinations are currently under investigation. Our front-line combination in the setting of renal insufficiency is gemcitabine, taxol, and doxorubicin and is the subject of a currently accruing phase II clinical trial. Novel targeted agents are also a source of active research,88,89 but these have not yet been definitively proved in the treatment of urothelial cancer.

1. Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

2. Cancer Research UK. CancerStats: Incidence—UK. 2008. Available at http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/epages/crukstore.sf/en_GB/?ObjectPath=/Shops/crukstore/Products/CSINC08

3. Skinner D.G., Richie J.P., Cooper P.H., et al. The clinical significance of carcinoma in situ of the bladder and its association with overt carcinoma. J Urol. 1974;112:68-71.

4. Lindell O., Lehtonen T. Upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma after total cystectomy for bladder cancer. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1985;74:288-293.

5. Williams C.B., Mitchell J.P. Carcinoma of the renal pelvis: a review of 43 cases. Br J Urol. 1973;45:370-376.

6. Fleshner N., Kondylis F. Demographics and epidemiology of urothelial cancer of the urinary bladder. In: Droller M., editor. Urothelial Tumors. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc.; 2004:1-16.

7. Radovanovic Z., Jankovic S., Jevremovic I. Incidence of tumors of urinary organs in a focus of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;34:S75-S76.

8. Stefanovic V., Radovanovic Z. Balkan endemic nephropathy and associated urothelial cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:105-112.

9. Yu Y., Hu J., Wang P.P., et al. Risk factors for bladder cancer: a case-control study in northeast China. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1997;6:363-369.

10. Tsai Y.C., Nichols P.W., Hiti A.L., et al. Allelic losses of chromosomes 9, 11, and 17 in human bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1990;50:44-47.

11. Epithelial tumors of the bladder. In: Mostofi F.K., editor. Histological Typing of Urinary Bladder Tumours. Berlin and New York: Springer-Verlag; 1999:15-16.

12. Siefker-Radtke A.O., Dinney C.P., Abrahams N.A., et al. Evidence supporting preoperative chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of the bladder: a retrospective review of the M. D. Anderson cancer experience. J Urol. 2004;172:481-484.

13. Siefker-Radtke A., Kamat A., Grossman B., et al. Final results from a phase II clinical trial of systemic chemotherapy in small cell urothelial cancer: evidence supporting neoadjuvant chemotherapy from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:255s.

14. Bostwick D.G., Ramnani D., Cheng L. Diagnosis and grading of bladder cancer and associated lesions. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:493-507.

15. Pashos C.L., Botteman M.F., Laskin B.L., Redaelli A. Bladder cancer: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:311-322.

16. Melamed M.R., Reuter V.E. Pathology and staging of urothelial tumors of the kidney and ureter. Urol Clin North Am. 1993;20:333-347.

17. MacVicar A.D. Bladder cancer staging. BJU Int. 2000;86(Suppl 1):111-122.

18. Knap M.M., Lundbeck F., Overgaard J. Prognostic factors, pattern of recurrence and survival in a Danish bladder cancer cohort treated with radical cystectomy. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:160-168.

19. Browne R.F., Meehan C.P., Colville J., et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: spectrum of imaging findings. Radiographics. 2005;25:1609-1627.

20. Buckley J.A., Urban B.A., Soyer P., et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis: a retrospective look at CT staging with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1996;201:194-198.

21. Husband J.E. Bladder cancer. In: Husband J.E.S., Reznek R.H. Imaging in Oncology. Oxford: Isis Medical Media; 1998:215-238.

22. Oosterlinck W., Lobel B., Jakse G., et al. Guidelines on bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2002;41:105-112.

23. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Stat Fact Sheets. 2009. National Cancer Institute. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html (accessed February 9, 2010)

24. Gschwend J.E., Dahm P., Fair W.R. Disease specific survival as endpoint of outcome for bladder cancer patients following radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2002;41:440-448.

25. Kantoff P.W., Zeitman A.L., Wishnow K. Bladder cancer. In: Bast R.C., Kufe D.W., Pollock R.E., et al. Cancer Medicine. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc.; 2000:1543-1558.

26. Jewett H., Strong G. Infiltrating carcinoma of the bladder: relation of depth of penetration of the bladder wall to incidence of local extension in metastases. J Urol. 1946;55:366-372.

27. Marshall V.F. The relationship of the preoperative estimate to the pathologic demonstration of the extent of vesical neoplasms. J Urol. 1952;68:714-723.

28. Whitmore W.F.Jr. Assessment and management of deeply invasive and metastatic lesions. Cancer Res. 1977;37:2756-2758.

29. Levy D.A., Grossman H.B. Staging and prognosis of T3b bladder cancer. Semin Urol Oncol. 1996;14:56-61.

30. Barentsz J.O., Jager G.J., Witjes J.A. MR imaging of the urinary bladder. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 2000;8:853-867.

31. Vock P., Haertel M., Fuchs W.A., et al. Computed tomography in staging of carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Br J Urol. 1982;54:158-163.

32. Sager E.M., Talle K., Fossa S., et al. The role of CT in demonstrating perivesical tumor growth in the preoperative staging of carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Radiology. 1983;146:443-446.

33. Fisher M.R., Hricak H., Crooks L.E. Urinary bladder MR imaging. Part I. Normal and benign conditions. Radiology. 1985;157:467-470.

34. Fisher M.R., Hricak H., Tanagho E.A. Urinary bladder MR imaging. Part II. Neoplasm. Radiology. 1985;157:471-477.

35. Amendola M.A., Glazer G.M., Grossman H.B., et al. Staging of bladder carcinoma: MRI-CT-surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:1179-1183.

36. Rholl K.S., Lee J.K., Heiken J.P., et al. Primary bladder carcinoma: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1987;163:117-121.

37. Buy J.N., Moss A.A., Guinet C., et al. MR staging of bladder carcinoma: correlation with pathologic findings. Radiology. 1988;169:695-700.

38. Koelbel G., Schmiedl U., Griebel J., et al. MR imaging of urinary bladder neoplasms. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1988;12:98-103.

39. Husband J.E., Olliff J.F., Williams M.P., et al. Bladder cancer: staging with CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;173:435-440.

40. Neuerburg J.M., Bohndorf K., Sohn M., et al. Urinary bladder neoplasms: evaluation with contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172:739-743.

41. Tavares N.J., Demas B.E., Hricak H. MR imaging of bladder neoplasms: correlation with pathologic staging. Urol Radiol. 1990;12:27-33.

42. Tachibana M., Baba S., Deguchi N., et al. Efficacy of gadolinium-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for differentiation between superficial and muscle-invasive tumor of the bladder: a comparative study with computerized tomography and transurethral ultrasonography. J Urol. 1991;145:1169-1173.

43. Tanimoto A., Yuasa Y., Imai Y., et al. Bladder tumor staging: comparison of conventional and gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MR imaging and CT. Radiology. 1992;185:741-747.

44. Doringer E. Computerized tomography of colonic diverticulitis. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1992;33:421-435.

45. Kim B., Semelka R.C., Ascher S.M., et al. Bladder tumor staging: comparison of contrast-enhanced CT, T1- and T2-weighted MR imaging, dynamic gadolinium-enhanced imaging, and late gadolinium-enhanced imaging. Radiology. 1994;193:239-245.

46. Barentsz J.O., Jager G., Mugler J.P.3rd, et al. Staging urinary bladder cancer: value of T1-weighted three-dimensional magnetization prepared-rapid gradient-echo and two-dimensional spin-echo sequences. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:109-115.

47. Barentsz J.O., Jager G.J., van Vierzen P.B., et al. Staging urinary bladder cancer after transurethral biopsy: value of fast dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201:185-193.

48. Barentsz J.O., Witjes J.A., Ruijs J.H. What is new in bladder cancer imaging. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:583-602.

49. Caterino M., Finocchi V., Giunta S., et al. Bladder cancer within a direct inguinal hernia: CT demonstration. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:664-666.

50. Schuller J., Walther V., Schmiedt E., et al. Intravesical ultrasound tomography in staging bladder carcinoma. J Urol. 1982;128:264-266.

51. Abu-Yousef M.M., Narayana A.S., Brown R.C., Franken E.A.Jr. Urinary bladder tumors studied by cystosonography. Part II: staging. Radiology. 1984;153:227-231.

52. Dershaw D.D., Scher H.I. Sonography in evaluation of carcinoma of bladder. Urology. 1987;29:454-457.

53. Meissner C., Giannarini G., Schumacher M.C., et al. The efficiency of excretory urography to detect upper urinary tract tumors after cystectomy for urothelial cancer. J Urol. 2007;178:2287-2290.

54. Miyake H., Hara I., Yamanaka K., et al. Limited significance of routine excretory urography in the follow-up of patients with superficial bladder cancer after transurethral resection. BJU Int. 2006;97:720-723.

55. Chow L.C., Kwan S.W., Olcott E.W., Sommer G. Split-bolus MDCT urography with synchronous nephrographic and excretory phase enhancement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:314-322.

56. Caoili E.M., Cohan R.H., Inampudi P., et al. MDCT urography of upper tract urothelial neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1873-1881.

57. Wong-You-Cheong J.J., Wagner B.J., Davis C.J.Jr. Transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1998;18:123-142. quiz 148

58. Chlapoutakis K., Theocharopoulos N., Yarmenitis S., Damilakis J. Performance of computed tomographic urography in diagnosis of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma, in patients presenting with hematuria: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:334-338.

59. Albani J.M., Ciaschini M.W., Streem S.B., et al. The role of computerized tomographic urography in the initial evaluation of hematuria. J Urol. 2007;177:644-648.

60. Gray Sears C.L., Ward J.F., Sears S.T., et al. Prospective comparison of computerized tomography and excretory urography in the initial evaluation of asymptomatic microhematuria. J Urol. 2002;168:2457-2460.

61. Cowan N.C., Turney B.W., Taylor N.J., et al. Multidetector computed tomography urography for diagnosing upper urinary tract urothelial tumour. BJU Int. 2007;99:1363-1370.

62. Koss J.C., Arger P.H., Coleman B.G., et al. CT staging of bladder carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:359-362.

63. Hofer C., Kubler H., Hartung R., et al. Diagnosis and monitoring of urological tumors using positron emission tomography. Eur Urol. 2001;40:481-487.

64. Husband J.E. Computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of bladder cancer. J Belge Radiol. 1995;78:350-355.

65. Jager G.J., Barentsz J.O., Oosterhof G.O., et al. Pelvic adenopathy in prostatic and urinary bladder carcinoma: MR imaging with a three-dimensional TI-weighted magnetization-prepared-rapid gradient-echo sequence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1503-1507.

66. Deserno W.M., Harisinghani M.G., Taupitz M., et al. Urinary bladder cancer: preoperative nodal staging with ferumoxtran-10-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2004;233:449-456.

67. Hain S.F., Maisey M.N. Positron emission tomography for urological tumours. BJU Int. 2003;92:159-164.

68. Gore J.L., Lai J., Setodji C.M., et al. Mortality increases when radical cystectomy is delayed more than 12 weeks: results from a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:988-996.

69. Brassell S.A., Kamat A.M. Contemporary intravesical treatment options for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:1027-1036.

70. Herring J.C., Kamat A.M. Treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: progress and new challenges. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2004;4:1047-1056.

71. Kamat A.M., Dinney C.P., Gee J.R., et al. Micropapillary bladder cancer: a review of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience with 100 consecutive patients. Cancer. 2007;110:62-67.

72. Kamat A.M., Fisher M.B. Lymph node density: surrogate marker for quality of resection in bladder cancer? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:777-779.

73. Lamm D.L., Blumenstein B.A., Crissman J.D., et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163:1124-1129.

74. Sternberg C.N., Yagoda A., Scher H.I., et al. Preliminary results of M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) for transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. J Urol. 1985;133:403-407.

75. Logothetis C.J., Dexeus F.H., Finn L., et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing MVAC and CISCA chemotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1050-1055.

76. Siefker-Radtke A.O., Millikan R.E., Tu S.M., et al. Phase III trial of fluorouracil, interferon alpha-2b, and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in metastatic or unresectable urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1361-1367.

77. Bamias A., Aravantinos G., Deliveliotis C., et al. Docetaxel and cisplatin with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) versus MVAC with G-CSF in advanced urothelial carcinoma: a multicenter, randomized, phase III study from the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:220-228.

78. Grossman H.B., Natale R.B., Tangen C.M., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:859-866.

79. von der Maase H., Hansen S.W., Roberts J.T., et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068-3077.

80. Sternberg C.N., de Mulder P.H., Schornagel J.H., et al. Randomized phase III trial of high-dose-intensity methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) chemotherapy and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor versus classic MVAC in advanced urothelial tract tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Protocol no. 30924. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2638-2646.

81. Brown G.A., Matin S.F., Busby J.E., et al. Ability of clinical grade to predict final pathologic stage in upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: implications for therapy. Urology. 2007;70:252-256.

82. Grossman H., Soloway M., Messing E., et al. Surveillance for recurrent bladder cancer using a point-of-care proteomic assay. JAMA. 2006;295:299-305.

83. Bajorin D.F., McCaffrey J.A., Dodd P.M., et al. Ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin for patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract: final report of a phase II trial evaluating two dosing schedules. Cancer. 2000;88:1671-1678.

84. Siefker-Radtke A.O., Millikan R.E., Kamat A.M., et al. A phase II trial of sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy with ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine (IAG), followed by cisplatin, gemcitabine and ifosfamide (CGI) in locally advanced urothelial cancer (UC): final results from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. 2008 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition). May 30June 32008ChicagoJ Clin Oncol. 2008;26:269s.

85. Siefker-Radtke A.O., Kamat A.M., Grossman H.B., et al. Phase II clinical trial of neoadjuvant alternating doublet chemotherapy with ifosfamide/doxorubicin and etoposide/cisplatin in small-cell urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2592-2597.

86. Pagliaro L.C., Millikan R.E., Tu S.M., et al. Cisplatin, gemcitabine, and ifosfamide as weekly therapy: a feasibility and phase II study of salvage treatment for advanced transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2965-2970.

87. Tu S.M., Hossan E., Amato R., et al. Paclitaxel, cisplatin and methotrexate combination chemotherapy is active in the treatment of refractory urothelial malignancies. J Urol. 1995;154:1719-1722.

88. Hussain M., Petrylak D., Dunn R., et al. Trastuzumab (T), paclitaxel (P), carboplatin (C), and gemcitabine (G) in advanced HER2-positive urothelial carcinoma: Results of a multi-center phase II NCI trial. 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. May 13172005OrlandoJ Clin Oncol. 2005;26:379s.

89. Sridhar S.S., Strader W., Le L., et al. Phase II study of bortezomib in advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer. A trial of the Princess Margaret Hospital [PMH] Phase II Consortium. 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. Orlando J Clin Oncol. May 13-17 2005;26:422s.

90. Bladder cancer. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:569-577

91. Renal pelvis & ureter. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:561-567